Pancake tortoise

| Pancake tortoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Malacochersus Lindholm, 1929 |

| Species: | M. tornieri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Malacochersus tornieri (Siebenrock, 1903)

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

The pancake tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri) is a species of flat-shelled tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is native to Tanzania and Kenya. There are also small populations in northern Zambia.[4] Its common name refers to the flat shape of its shell.

Etymology

[edit]Both the specific name, tornieri, and an alternate common name, Tornier's tortoise, are in honor of German zoologist Gustav Tornier.[5]

Taxonomy

[edit]Malacochersus tornieri is the only member of its genus.[3]

Description

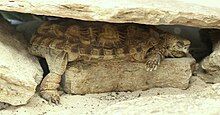

[edit]The pancake tortoise has an unusually thin, flat, flexible shell, which is up to 17.8 centimetres (7.0 in) long.[6][7] While the shell bones of most other tortoises are solid, the pancake tortoise has shell bones with many openings, making it lighter and more agile than other tortoises.[8] On the rear of its shell, it has a highly ossified lump that is different from the rest of its bone structure.[9] The carapace (top shell) is brown, frequently with a variable pattern of radiating dark lines on each scute (shell plate), helping to camouflage the tortoise in its natural dry habitat.[6][8][10] The plastron (bottom shell) is pale yellow with dark brown seams and light yellow rays,[10] and the head, limbs and tail are yellow-brown.[6] Its bizarre, flattened, pancake-like profile makes this tortoise a sought-after animal in zoological and private collections, leading to its over-exploitation in the wild.[11]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]An East African species, M. tornieri is native to southern Kenya and northern and eastern Tanzania,[10] and an introduced population may also occur in Zimbabwe.[1] The species has also been reported in Zambia.[12] It is found on hillsides with rocky outcrops (known as kopjes) in arid thorn scrub and savanna, from 100 to 6,000 feet (30 to 1800 metres) above sea level.[7][10][13] The species inhabits the Somalia-Masai floristic region, an arid semi-desert characterized by Acacia-Commiphora bushland and Brachystegia woodland in upland localities.[14][15] It occurs in dry savannah of low altitude at small rocky hills of the crystalline basement.

Ecology and behaviour

[edit]

Pancake tortoises live in isolated colonies, with many individuals sharing the same kopje, or even crevice.[10] Males fight for access to females during the mating season, in January and February, with large males tending to get the most chances to mate.[6][10] Nesting in the wild seems to occur in July and August, although clutches are produced year-round in captivity. The female digs a nest cavity about 7.5 to 10 cm deep in loose, sandy soil.[6] Usually only one egg is laid at a time, but a female can lay multiple eggs over the course of a single season, with eggs appearing every four to eight weeks.[6][8] In captivity, the incubation of the eggs lasts from four to six months,[10] and young are independent as soon as they hatch.[16] Wild and captive specimens often bask and, although they do not appear to hibernate, there are reports that they may aestivate beneath flat rocks during the hottest months.[6][8]

Most activity occurs during the morning hours or in the late afternoon and early evening. The diet primarily consists of dry grasses and vegetation. The pancake tortoise is a fast and agile climber, and is rarely found far from its rocky home so that, if disturbed, it can make a dash for the nearest rock crevice.[6] Since this tortoise could easily be torn apart by predators, it must rely on its speed and flexibility to escape from dangerous situations, rather than withdrawing into its shell.[10] The flexibility of its shell allows the pancake tortoise to crawl into narrow rock crevices to avoid potential predators,[6] thus exploiting an environment that no other tortoise is capable of using.[11] There are two hypotheses about how the pancake tortoise is able to wedge itself in rock crevices: The first is that it presses its ossified lump to the ceiling of the rock crevice using its hind legs, or it 'inflates' an unossified portion in the plastron with air.[17]

Threats and conservation

[edit]The greatest threats facing the pancake tortoise are habitat destruction and its over-exploitation by the pet trade.[13] Given the low reproductive rate of this tortoise, populations that have been harvested may take a long time to recover. Commercial development diminishes the amount of suitable habitat for pancake tortoises, which already is neither common nor extensive.[11] Tortoises in Kenya are threatened by clearance of thorn scrub for conversion to agriculture and in Tanzania by over-grazing of goats and cattle.[13]

The pancake tortoise is classified as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List and listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[1][13] In 1981, Kenya banned the export of the pancake tortoise unless given written permission by the Minister for the Environment and Natural Resources. Tanzania protects this species under the Wildlife Conservation (National Game) Order, 1974,[13] and it is protected within the Serengeti National Park.[8] The European Union banned the import of the pancake tortoise in 1988, but trade with EU members continues, with several countries having reported importing the species.[13] The pancake tortoise has been bred in captivity and is now the subject of a coordinated breeding programme in European zoos.[16]

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Pancake tortoise" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- ^ a b c Mwaya, R.T.; Malonza, P.K.; Ngwava, J.M.; Moll, D.; Schmidt, F.A.C.; Rhodin, A.G.J. (2019). "Malacochersus tornieri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12696A508210. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T12696A508210.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 287. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. ISSN 1864-5755.

- ^ Eustace A, Esser LF, Mremi R, Malonza PK, Mwaya RT (2021) Protected areas network is not adequate to protect a critically endangered East Africa Chelonian: Modelling distribution of pancake tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri under current and future climates. PLOS ONE 16(1): e0238669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238669

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Malacochersus tornieri, p. 266).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Turtles of the World Archived 2007-06-21 at archive.today (CD-ROM), by Ernst CH, Altenburg RGM, Barbour RW (February 2007).

- ^ a b Connor MJ (1992). "Pancake Tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri ". Tortuga Gazette 28 (11): 1-3.

- ^ a b c d e Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens Archived 2006-02-25 at the Wayback Machine (February 2007).

- ^ Mautner, A.-K., Latimer, A.E., Fritz, U. and Scheyer, T.M. (2017), An updated description of the osteology of the pancake tortoise Malacochersus tornieri (Testudines: Testudinidae) with special focus on intraspecific variation. Journal of Morphology, 278: 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20640

- ^ a b c d e f g h WhoZoo: Animals of the Fort Worth Zoo (February 2007).

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick DT (2007). An Overview of the Natural History of the Pancake Tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri ". Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chansa & Wagner (2006).

- ^ a b c d e f CITES: Consideration of Proposals for Amendment of Appendices I and II Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Prop. 11.39 (February 2007).

- ^ White (1983).

- ^ Broadley & Howell (1991).

- ^ a b Bristol Zoo Gardens Archived 2009-04-03 at the Wayback Machine (February 2007).

- ^ Mautner, A.-K., Latimer, A.E., Fritz, U. and Scheyer, T.M. (2017), An updated description of the osteology of the pancake tortoise Malacochersus tornieri (Testudines: Testudinidae) with special focus on intraspecific variation. Journal of Morphology, 278: 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20640

External links

[edit]- Pancake Tortoise by Reptile Amphibian Information

- pancake-tortoise/malacochersus-tornieri Pancake tortoise media from ARKive

Further reading

[edit]- Broadley DG, Howell KM (1991). "A check list of the reptiles of Tanzania, with synoptic keys". Syntarsus 1: 1–70. (Malacochersus tornieri, p. 8).

- Chansa W, Wagner P (2006). "On the status of Malacochersus tornieri (Siebenrock, 1903) in Zambia". Salamandra 42 (2/3): 187–190.

- Siebenrock F (1903). "Über zwei seltene und eine neue Schildkröte des Berliner Museums ". Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaften Klasse 112: 439-445 + one unnumbered plate. (Testudo tornieri, new species, pp. 443–445 + unnumbered plate, figures 1-3). (in German).

- Spawls, Stephen; Howell, Kim; Hinkel, Harald; Menegon, Michele (2018). Field Guide to East African Reptiles, Second Edition. London: Bloomsbury Natural History. 624 pp. ISBN 978-1472935618. (Malacochersus tornieri, p. 35).

- White F (1983). The Vegetation of Africa. Paris: UNESCO Press. 356 pp.