Marie Pauline Brenner

Marie Pauline Brenner | |

|---|---|

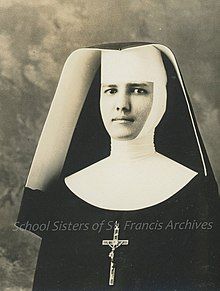

Brenner in 1926 | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 1906 |

| Died | 1978 (aged 71–72) |

| Resting place | Mount Olivet Cemetery Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Known for | Catholic social studies pioneer |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Order | School Sisters of St. Francis |

| Monastic name | Sister M. Rebecca |

M. Rebecca Brenner, OSF (born Marie Pauline Brenner; 15 December 1906 – 6 August 1978),[1] was an American religious educator who helped establish sociology as a discipline in Catholic secondary education. Based in Chicago, she was a member of the School Sisters of St. Francis.

Biography

[edit]Marie Pauline Brenner was born in 1906, the daughter of Aquilin and Rosa Brenner. Aquilin had emigrated from Steinbach, Bavaria in 1874. Rosa (Weber) Brenner emigrated from Sulz, Switzerland in 1884. They married in 1890 and settled in the St. Paul area of Minnesota. In 1926 at the age of 20, Marie joined the School Sisters of St. Francis, a religious order with a focus on teaching. The order had been established in Schwarzach Germany during the reign of Otto von Bismarck. Their first school was opened in Wilmette, IL in 1877.[2][3] Upon joining the order, Marie took the name of Sister Rebecca. She was assigned to teach fourth through seventh grades at St. Nicholas School Aurora, IL.[1]

Brenner later attended DePaul University and earned a bachelor's degree in social science. In 1937 she began teaching at Alvernia, an all girls Catholic High School in Chicago. Along with teaching religion, Latin, and American history, Brenner began teaching sociology, putting her social science background into action. This was a departure from traditional approaches to Catholic education, which emphasized rote learning. At this time, a movement was stirring in religious circles that religion was not only about catechism questions and answers, but about loving one's neighbor no matter their race, ethnicity, or social status. This movement followed trends in general education which emphasized merging theory and practice, sometimes known as praxis. A famous line from Karl Marx states that "Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; what is important is to transform it."[4] Brenner taught at Alvernia for fifteen years, from 1937 to 1952. She was known for encouraging her students to open their minds to the needs of the world and to their potential as women.[1]

During this time also, she attended Notre Dame University and earned a master's degree in 1944. In her thesis, Brenner examined religious patterns among Italian immigrants. She quotes from various sources that debate whether or not Italian immigrants to the United States can be considered religious. The criterion for whether or not they were religious was whether they attended Mass on Sundays. She concludes in this section that "masses of people in Italy . . . go to church" but that "there is considerable falling off from regular church attendance after they migrate to America".[5] Through interviews with priests and social workers, five reasons or circumstances are responsible for this "falling off." Among the reasons are their lack of education and proselytizing by Protestant religions.[6]

In 1952 Brenner moved to Milwaukee to teach at Alverno College where she set up their program in sociology. As in Chicago, she encouraged students to engage in critical analysis of social issues in her classes at Alverno. At the same time she continued her own education at Marquette University, Catholic University of America, and St. Louis University. In 1966 she went back to high school teaching at St. Joseph Convent High School which closed in 1966.[1]

Brenner died of cancer at age 71. She is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[1]

Influence on Catholic education and social justice activism

[edit]Brenner set up one of the first courses in sociology in a Catholic school.[1] She believed that a classroom education needed to be supplemented by first hand experience in the community. She assigned her students to investigate and report on the conditions of Chicago public housing, child care centers, Cook County prison and court facilities.[1][6] In her classes at Alvernia, Brenner instructed her students about the spiritual, material, and physical disadvantages of the immigrant. Along with her students, she examined the causes of poverty and crime, and advocated a more aggressive role for the church.[1]

Brenner influenced a generation of students, many of whom who went on to engage in service work or activism on social causes. In particular, members of the School Sisters of St. Francis began to participate in demonstrations and activism on racial justice during the civil rights era. Pat Seng, a student of Brenner's at Alvernia in the 1950s, volunteered at Friendship House in Chicago as a student. Known as the Martin de Porres Friendship House, the Friendship House in Chicago was a meeting place for Catholics interested in social justice, particularly racial justice.[7] After her studies, Seng joined the School Sisters of St. Francis and chose the name Sister Angelica. Inspired by Brenner, her mentor, she led a group of Sisters who protested against the Illinois Women's Club of Chicago based at Loyola University's downtown campus, because the Club did not allow black members. They were the first group of Catholic women religious to play a leading role in a public demonstration on racial segregation in Chicago.[3][8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Michaelsen, Terry J. (2001). "Sister Rebecca Brenner". In Schultz, Rima L. (ed.). Women Building Chicago. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 116–118. ISBN 9780253338525.

- ^ Borgia, Francis, Sister M. (1965). He Sent Two: The Story of the Beginning of the School sisters of St. Francis. Milwaukee Wisconsin: The Seraphic Press. pp. 7–8, 75.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hoy, Suellen M. (2006). Good hearts : Catholic sisters in Chicago's past. Urbana [Ill]: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-03057-5. OCLC 61229676.

- ^ Naas, Michael (June 3, 2020). "Education in Theory and Practice: Derrida's Enseignement Superieur". Studies in Philosophy and Education. 40 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1007/s11217-020-09723-y – via EBSCO Magazines & Journals.

- ^ Brenner, Sister Rebecca, O.S.F. (1944). Churchgoing Among Our Italian Immigrants: A Dissertation Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Study of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts. p. 45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Brenner, Sister Rebecca, O.S.F. (1944). Churchgoing Among Our Italian Immigrants: A Dissertation Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Study of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts. p. 80.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Friendship House, Chicago". chsmedia.org. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

- ^ "The Pool in Lewis Towers: Segregation at Loyola". The Loyola Phoenix. October 6, 2020.