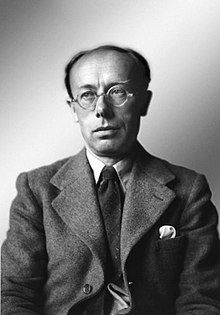

Max Newman

Max Newman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Maxwell Herman Alexander Neumann 7 February 1897[4] Chelsea, London, England |

| Died | 22 February 1984 (aged 87) Cambridge, England |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Elements of the topology of plane sets of points[5] Newman's lemma Newmanry section at Bletchley Park Heath Robinson (codebreaking machine) Colossus computer Newman's problem |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Edward and William |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society (1939)[1] Sylvester Medal (1958) De Morgan Medal (1962) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge University of Manchester Princeton University |

| Doctoral students | Sze-Tsen Hu Gilbert Robinson Hsien Chung Wang[2][3] |

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS[1] (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus,[6] the world's first operational, programmable electronic computer, and he established the Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory at the University of Manchester, which produced the world's first working, stored-program electronic computer in 1948, the Manchester Baby.[7][8][9][10][11]

Early life and education

[edit]Newman was born Maxwell Herman Alexander Neumann in Chelsea, London, England, to a Jewish family, on 7 February 1897.[4] His father was Herman Alexander Neumann, originally from the German city of Bromberg (now in Poland), who had emigrated with his family to London at the age of 15.[12] Herman worked as a secretary in a company, and married Sarah Ann Pike, an Irish schoolteacher, in 1896.[1]

The family moved to Dulwich in 1903, and Newman attended Goodrich Road school, then City of London School from 1908.[1][13] At school, he excelled in classics and in mathematics. He played chess and the piano well.[14]

Newman won a scholarship to study mathematics at St John's College, Cambridge in 1915, and in 1916 gained a First in Part I of the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos.[4]

World War I

[edit]Newman's studies were interrupted by World War I. His father was interned as an enemy alien after the start of the war in 1914, and upon his release he returned to Germany. In 1916, Herman changed his name by deed poll to the anglicised "Newman" and Sarah did likewise in 1920.[15] In January 1917, Newman took up a teaching post at Archbishop Holgate's Grammar School in York, leaving in April 1918. He spent some months in the Royal Army Pay Corps, and then taught at Chigwell School for six months in 1919 before returning to Cambridge.[12] He was called up for military service in February 1918, but claimed conscientious objection due to his beliefs and his father's country of origin, and thereby avoided any direct role in the fighting.[16]

Between the wars

[edit]Graduation

[edit]Newman resumed his interrupted studies in October 1919, and graduated in 1921 as a Wrangler (equivalent to a First) in Part II of the Mathematical Tripos, and gained distinction in Schedule B (the equivalent of Part III).[4][12] His dissertation considered the use of "symbolic machines" in physics, foreshadowing his later interest in computing machines.[14]

Early academic career

[edit]On 5 November 1923, Newman was elected a Fellow of St John's.[1] He worked on the foundations of combinatorial topology, and proposed that a notion of equivalence be defined using only three elementary "moves".[4] Newman's definition avoided difficulties that had arisen from previous definitions of the concept.[4] Publishing over twenty papers established his reputation as an "expert in modern topology".[14] Newman wrote Elements of the topology of plane sets of points,[5] a work on general topology and undergraduate text.[17] He also published papers on mathematical logic, and solved a special case of Hilbert's fifth problem.[1]

He was appointed a lecturer in mathematics at Cambridge in 1927.[4] His 1935 lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics and Gödel's theorem inspired Alan Turing to embark on his work on the Entscheidungsproblem (decision problem) that had been posed by Hilbert and Ackermann in 1928.[18] Turing's solution involved proposing a hypothetical programmable computing machine.[19] In spring 1936, Newman was presented by Turing with a draft of "On Computable Numbers with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". He realised the paper's importance and helped ensure swift publication.[14] Newman subsequently arranged for Turing to visit Princeton where Alonzo Church was working on the same problem but using his Lambda calculus.[12] During this period, Newman started to share Turing's dream of building a stored-program computing machine.[20]

During this time at Cambridge, he developed close friendships with Patrick Blackett, Henry Whitehead and Lionel Penrose.[14]

In September 1937, Newman and his family accepted an invitation to work for six months at Princeton. At Princeton, he worked on the Poincaré Conjecture and, in his final weeks there, presented a proof. However, in July 1938, after he returned to Cambridge, Newman discovered that his proof was fatally flawed.[14]

In 1939, Newman was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[14]

Family life

[edit]In December 1934, he married Lyn Lloyd Irvine, a writer, with Patrick Blackett as best man.[1] They had two sons, Edward (born 1935) and William (born 1939).[12]

World War II

[edit]The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939. Newman's father was Jewish, which was of particular concern in the face of Nazi Germany, and Lyn, Edward and William were evacuated to America in July 1940, where they spent three years before returning to England in October 1943. After Oswald Veblen — maintaining 'that every able-bodied man ought to be carrying a gun or hand-grenade and fight for his country'— opposed moves to bring him to Princeton, Newman remained at Cambridge and at first continued research and lecturing.[12]

Government Code and Cypher School

[edit]By spring 1942, Newman was considering involvement in war work. He made enquiries. After Patrick Blackett recommended him to the Director of Naval Intelligence, Newman was sounded out by Frank Adcock in connection with the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.[12]

Newman was cautious, concerned to ensure that the work would be sufficiently interesting and useful, and there was also the possibility that his father's German nationality would rule out any involvement in top-secret work.[21] The potential issues were resolved by the summer, and he agreed to arrive at Bletchley Park on 31 August 1942. Newman was invited by F. L. (Peter) Lucas to work on Enigma but decided to join Tiltman's group working on Tunny.[12]

Tunny

[edit]Newman was assigned to the Research Section and set to work on a German teleprinter cipher known as "Tunny". He joined the "Testery" in October.[22] Newman enjoyed the company[14] but disliked the work and found that it was not suited to his talents.[4] He persuaded his superiors that Tutte's method could be mechanised, and he was assigned to develop a suitable machine in December 1942. Shortly afterwards, Edward Travis (then operational head of Bletchley Park) asked Newman to lead research into mechanised codebreaking.[12]

The Newmanry

[edit]When the war ended, Newman was presented with a silver tankard inscribed 'To MHAN from the Newmanry, 1943–45'.[14]

Heath Robinson

[edit]Construction started in January 1943, and the first prototype was delivered in June 1943.[23] It was operated in Newman's new section, termed the "Newmanry", was housed initially in Hut 11 and initially staffed by himself, Donald Michie, two engineers, and 16 Wrens.[24] The Wrens nicknamed the machine the "Heath Robinson", after the cartoonist of the same name who drew humorous drawings of absurd mechanical devices.[24]

Colossus

[edit]The Robinson machines were limited in speed and reliability. Tommy Flowers of the Post Office Research Station, Dollis Hill had experience of thermionic valves and built an electronic machine, the Colossus computer which was installed in the Newmanry. This was a great success and ten were in use by the end of the war.

Later academic career

[edit]Fielden Chair, Victoria University of Manchester

[edit]In September 1945, Newman was appointed head of the Mathematics Department and to the Fielden Chair of Pure Mathematics at the University of Manchester.[20][25]

Computing Machine Laboratory

[edit]I am ... hoping to embark on a computing machine section here, having got very interested in electronic devices of this kind during the last two or three years ... I am of course in close touch with Turing.

— Newman, letter to von Neumann, 1946[20]

Newman lost no time in establishing the renowned Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory at the University.[25] In February 1946, he wrote to John von Neumann, expressing his desire to build a computing machine.[20] The Royal Society approved Newman's grant application in July 1946.[20] Frederic Calland Williams and Thomas Kilburn, experts in electronic circuit design, were recruited from the Telecommunications Research Establishment.[20][25] Kilburn and Williams built Baby, the world's first electronic stored-program digital computer based on Alan Turing's and John von Neumann's ideas.[20][25]

Now let's be clear before we go any further that neither Tom Kilburn nor I knew the first thing about computers when we arrived at Manchester University... Newman explained the whole business of how a computer works to us.

After the Automatic Computing Engine suffered delays and set backs, Turing accepted Newman's offer and joined the Computer Machine Laboratory in May 1948 as Deputy Director (there being no Director). Turing joined Kilburn and Williams to work on Baby's successor, the Manchester Mark I. Collaboration between the University and Ferranti later produced the Ferranti Mark I, the first mass-produced computer to go on sale.[20]

Retirement

[edit]Newman retired in 1964 to live in Comberton, near Cambridge. After Lyn's death in 1973, he married Margaret Penrose, widow of his friend Lionel Penrose, father of Sir Roger Penrose.[14][26]

He continued to do research on combinatorial topology during a period when England was a major centre of activity notably Cambridge under the leadership of Christopher Zeeman. Newman made important contributions leading to an invitation to present his work at the 1962 International Congress of Mathematicians in Stockholm at the age of 65, and proved a Generalized Poincaré conjecture for topological manifolds in 1966.

At the age of 85, Newman began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease. He died in Cambridge two years later.[14]

Honours

[edit]- Fellow of the Royal Society, elected 1939

- Royal Society Sylvester Medal, awarded 1958

- London Mathematical Society, President 1949–1951

- LMS De Morgan Medal, awarded 1962

- D.Sc. University of Hull, awarded 1968

The Newman Building at Manchester was named in his honour. The building housed the pure mathematicians from the Victoria University of Manchester between moving out of the Mathematics Tower in 2004 and July 2007 when the School of Mathematics moved into its new Alan Turing Building, where a lecture room is named in his honour.

In 1946, Newman declined the offer of an OBE as he considered the offer derisory.[24] Alan Turing had been appointed an OBE six months earlier and Newman felt that it was inadequate recognition of Turing's contribution to winning the war, referring to it as the "ludicrous treatment of Turing".[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Adams, J. F. (1985). "Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman. 7 February 1897–22 February 1984". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 31: 436–452. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1985.0015. S2CID 62649711.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Max Newman", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Max Newman at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wylie, Shaun (2004). "Newman, Maxwell Herman Alexander (1897–1984)". In Good, I. J (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31494. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Newman, Max (1939). Elements of the topology of plane sets of points. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24956-3.

- ^ Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Jack Copeland. "The Modern History of Computing". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ The Papers of Max Newman, St John's College Library

- ^ The Newman Digital Archive, St John's College Library & The University of Portsmouth

- ^ Anderson, David (2013). "Max Newman: Forgotten Man of Early British Computing". Communications of the ACM. 56 (5): 29–31. doi:10.1145/2447976.2447986. S2CID 1904488.

- ^ Max Newman publications indexed by Microsoft Academic

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j William Newman, "Max Newman – Mathematician, Codebreaker and Computer Pioneer", pp. 176–188 in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Heard, Terry (2010). "Max Newman's Medal". John Carpenter Club (City of London School Alumni). Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

the [John Carpenter Club] archive has recently acquired the Beaufoy Medal for Mathematics awarded to Max Newman in 1915

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Newman, William (2010). "14. Max Newman - Mathematician, Codebreaker, and Computer Pioneer". In Copeland, B. Jack (ed.). Colossus The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford University Press. pp. 176–188. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Anderson, D. (2007). "Max Newman: Topologist, Codebreaker, and Pioneer of Computing". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 29 (3): 76–81. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2007.4338447.

- ^ Paul Gannon, Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press, USA. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6. pp. 225–226.

- ^ Smith, P. A. (1939). "Review of Elements of the Topology of Plane Sets of Points by M. H. A. Newman" (PDF). Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 45 (11): 822–824. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1939-07087-0.

- ^ David Hilbert and Wilhlem Ackermann. Grundzüge der Theoretischen Logik. Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1928. English translation: David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann. Principles of Mathematical Logic. AMS Chelsea Publishing, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, 1950.

- ^ Turing, A. M. (1936). "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. 2. 42 (1) (published 1937): 230–265. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230. S2CID 73712.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Copeland, Jack (2010). "9. Colossus and the Rise of the Modern Computer". In Copeland, B. Jack (ed.). Colossus The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–100. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ Gannon, 2006, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Gannon, 2006, p. 228.

- ^ Jack Copeland with Catherine Caughey, Dorothy Du Boisson, Eleanor Ireland, Ken Myers, and Norman Thurlow, "Mr Newman's Section", p. 157 of pp. 158–175 in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ a b c Jack Copeland, "Machine against Machine", pp. 64–77 in B. Jack Copeland, ed., in Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957814-6.

- ^ a b c d Turing, Alan Mathison; Copeland, B. Jack (2004). The essential Turing: seminal writings in computing, logic, philosophy ... Oxford University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-19-825080-7. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ Prasannan, R (7 October 2020). "Tackling Sir Roger Penrose". The Week. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

External links

[edit]- Archival materials

- The Max Newman Digital Archive has digital copies of materials from the library of St. John's College, Cambridge.

- 1897 births

- 1984 deaths

- 20th-century cryptographers

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge

- 20th-century English mathematicians

- Bletchley Park people

- People educated at the City of London School

- Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge

- People from Chelsea, London

- Academics of the University of Manchester

- English conscientious objectors

- English Jews

- English people of German-Jewish descent

- Foreign Office personnel of World War II

- People from Comberton

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Royal Army Pay Corps soldiers

- Military personnel from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea