Sleeping Beauty

| The Sleeping Beauty | |

|---|---|

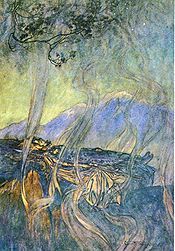

The prince finds the Sleeping Beauty, in deep slumber amidst the bushes. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Sleeping Beauty |

| Also known as | La Belle au bois dormant (The Beauty Sleeping in the Wood); Dornröschen (Little Briar Rose) |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 410 (Sleeping Beauty) |

| Region | France (1528) |

| Published in |

|

| Related | |

"Sleeping Beauty" (French: La Belle au bois dormant, or The Beauty Sleeping in the Wood[1][a]; German: Dornröschen, or Little Briar Rose), also titled in English as The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods, is a fairy tale about a princess cursed by an evil fairy to sleep for a hundred years before being awakened by a handsome prince. A good fairy, knowing the princess would be frightened if alone when she wakes, uses her wand to put every living person and animal in the palace and forest asleep, to awaken when the princess does.[6]

The earliest known version of the tale is found in the French narrative Perceforest, written between 1330 and 1344.[7] Another was the Catalan poem Frayre de Joy e Sor de Paser.[8] Giambattista Basile wrote another, "Sun, Moon, and Talia" for his collection Pentamerone, published posthumously in 1634–36[9] and adapted by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passé in 1697. The version collected and printed by the Brothers Grimm was one orally transmitted from the Perrault version,[10] while including own attributes like the thorny rose hedge and the curse.[11]

The Aarne-Thompson classification system for fairy tales lists Sleeping Beauty as a Type 410: it includes a princess who is magically forced into sleep and later woken, reversing the magic.[12] The fairy tale has been adapted countless times throughout history and retold by modern storytellers across various media.

Origin

[edit]Early contributions to the tale include the medieval courtly romance Perceforest (c. 1337–1344).[13] In this tale, a princess named Zellandine falls in love with a man named Troylus. Her father sends him to perform tasks to prove himself worthy of her, and while he is gone, Zellandine falls into an enchanted sleep. Troylus finds her, and rapes her in her sleep. They conceive and when their child is born, the child draws from her finger the flax that caused her sleep. She realizes from the ring Troylus left her that he was the father, and Troylus later returns to marry her.[14] Another early literary predecessor is the Provençal versified novel Fraire de Joi e sor de Plaser (c. 1320–1340).[15][16]

The second part of the Sleeping Beauty tale, in which the princess and her children are almost put to death but instead are hidden, may have been influenced by Genevieve of Brabant.[17] Even earlier influences come from the story of the sleeping Brynhild in the Volsunga saga and the tribulations of saintly female martyrs in early Christian hagiography conventions. Following these early renditions, the tale was first published by Italian poet Giambattista Basile who lived from 1575 to 1632.

Plot

[edit]

The folktale begins with a princess whose parents are told by a wicked fairy that their daughter will die when she pricks her finger on a particular item. In Basile's version, the princess pricks her finger on a piece of flax. In Perrault's and the Grimm Brothers' versions, the item is a spindle. The parents rid the kingdom of these items in the hopes of protecting their daughter, but the prophecy is fulfilled regardless. Instead of dying, as was foretold, the princess falls into a deep sleep. After some time, she is found by a prince and is awakened. In Giambattista Basile's version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty, Talia, falls into a deep sleep after getting a splinter of flax in her finger. She is discovered in her palace by a wandering king, who "carrie[s] her to a bed, where he gather[s] the first fruits of love."[18] He abandons her there after the assault and she later gives birth to twins while still unconscious.[19]

According to Maria Tatar, there are versions of the story that include a second part to the narrative that details the couple's troubles after their union; some folklorists believe the two parts were originally separate tales.[20]

The second part begins after the prince and princess have had children. Through the course of the tale, the princess and her children are introduced in some way to another woman from the prince's life. This other woman is not fond of the prince's new family, and calls a cook to kill the children and serve them for dinner. Instead of obeying, the cook hides the children and serves livestock. Next, the other woman orders the cook to kill the princess. Before this can happen, the other woman's true nature is revealed to the prince and then she is subjected to the very death that she had planned for the princess. The princess, prince, and their children live happily ever after.[21]

Basile's narrative

[edit]

In Giambattista Basile's dark version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty is named Talia. By asking wise men and astrologers to predict her future after her birth, her father, who is a great Lord, learns that Talia will be in danger from a splinter of flax. Talia, now grown, sees an old woman spinning outside her window. Intrigued by the sight of the twirling spindle, Talia invites the woman over and takes the distaff from her hand to stretch the flax. Tragically, the splinter of flax gets embedded under her nail, and she is put to sleep. After Talia falls asleep, she is seated on a velvet throne and her father, to forget his misery of what he thinks is her death, closes the doors and abandons the house forever. One day, while a king is walking by, one of his falcons flies into the house. The king knocks, hoping to be let in by someone, but no one answers, and he decides to climb in with a ladder. He finds Talia alive but unconscious, and "…gathers the first fruits of love."[22] Afterwards, he leaves her in bed and goes back to his kingdom. Though Talia is unconscious, she gives birth to twins—one of whom keeps sucking her finger. Talia awakens because the twin has sucked out the flax that got stuck in her finger. When she wakes up, she discovers that she is a mother and has no idea what happened to her. One day, the king decides he wants to go see Talia again. He goes back to the palace to find her awake and a mother to his twins. He informs her of who he is, what has happened, and they end up bonding. After a few days, the king has to leave to go back to his realm but promises Talia that he will return to take her to his kingdom.

When he arrives back in his kingdom, his wife hears him saying "Talia, Sun, and Moon" in his sleep. She bribes and threatens the king's secretary to tell her what is going on. After the queen learns the truth, she pretends she is the king and writes to Talia asking her to send the twins because he wants to see them. Talia sends her twins to the "king" and the queen tells the cook to kill the twins and make dishes out of them. She wants to feed the king his children; instead, the cook takes the twins to his wife and hides them. He then cooks two lambs and serves them as if they were the twins. Every time the king mentions how good the food is, the queen replies, "Eat, eat, you are eating of your own." Later, the queen invites Talia to the kingdom and is going to burn her alive, but the king appears and finds out what's going on with his children and Talia. He then orders that his wife be burned along with those who betrayed him. Since the cook actually did not obey the queen, the king thanks the cook for saving his children by giving him rewards. The story ends with the king marrying Talia and living happily ever after.[18]

Perrault's narrative

[edit]

Perrault's narrative is written in two parts, which some folklorists believe were originally separate tales, as they were in the Brothers Grimm's version, and were later joined together by Giambattista Basile and once more by Perrault.[20] According to folklore editors Martin Hallett and Barbara Karasek, Perrault's tale is a much more subtle and pared down version than Basile's story in terms of the more immoral details. An example of this is depicted in Perrault's tale by the prince's choice to instigate no physical interaction with the sleeping princess when he discovers her.[9]

At the christening of a king and queen's long-wished-for child, seven good fairies are invited to be the infant Princess's godmothers and give her gifts. The seven fairies attend the banquet at the palace and each is given a golden box containing golden utensils adorned with diamonds and rubies. Soon after, an old fairy enters the palace, overlooked because she has not left her tower in fifty years and everyone believed her to be cursed or dead. Nevertheless, the eighth fairy is seated and given a box of ordinary utensils. When she hears the eighth fairy muttering some threats, the seventh, fearing that the uninvited guest will harm the Princess, hides herself behind some curtains, so she can be the last to give a gift.

Six of the invited fairies offer their gifts of pure beauty, wit, grace, dance, song, and musical talent to the infant Princess. The eighth fairy, who is very angry about not being invited, curses the infant Princess so that she will one day prick her finger on a spindle of a spinning wheel and die. The seventh fairy then offers her gift: an attempt to reverse the evil fairy's curse, but she can only do so partially. Instead of dying, the Princess will fall into a deep sleep for 100 years and be awakened by a king's son ("elle tombera seulement dans un profond sommeil qui durera cent ans, au bout desquels le fils d’un Roi viendra la réveiller").

The King then orders all spinning wheels in the kingdom banned and destroyed in an attempt to avert the eighth fairy's curse on his daughter. Fifteen or sixteen years pass and one day, when the king and queen are away, the Princess wanders through the palace rooms and comes upon an old woman (implied to be the evil fairy in disguise), spinning with her spindle. The Princess, who has never seen a spinning wheel before, asks the old woman if she can try it. The curse is fulfilled when the princess pricks her finger on the spindle and instantly falls into a deep sleep. The old woman cries for help and attempts are made to revive the princess. The king attributes this to fate and has the Princess carried to the finest room in the palace and placed upon a bed of gold and silver embroidered fabric. The seventh fairy arrives in her dragon-drawn chariot. Having great powers of foresight, the fairy sees that the Princess will awaken to distress when she finds herself alone, so the fairy puts everyone in the castle, except the King and Queen, to sleep. The King and Queen kiss their daughter goodbye and leave the castle to ban others from disturbing her, but the good fairy summons a forest of trees, brambles and thorns to spring up around the place, shielding it from the outside world.

A hundred years pass and a prince from another royal family spies the hidden castle during a hunting expedition. His attendants tell him differing stories regarding the castle until an old man recounts his father's words: within the castle lies a very beautiful princess who is doomed to sleep for a hundred years until a king's son comes and awakens her. The prince then braves the tall trees, brambles and thorns which part at his approach, and enters the castle. He passes the sleeping castle folk and comes across the chamber where the Princess lies asleep on the bed. Struck by the radiant beauty before him, he falls on his knees before her. The spell is broken, the princess awakens and bestows upon the prince a look "more tender than a first glance might seem to warrant" (in Perrault's original French tale, the prince does not kiss the princess to wake her up) then converses with the prince for a long time. Meanwhile, the servants of the castle awaken and go about their business. The prince and princess are later married by the chaplain in the castle chapel.

After marrying the Sleeping Beauty in secret, the Prince visits her for four years and she bears him two children, unbeknownst to his mother, who is an ogre. When his father, the King, dies, the Prince ascends the throne and he brings his wife, who is now twenty years old, and their two children - a four-year-old daughter named Morning (Aurore or Dawn in the original French) and a three-year-old son named Day (Jour in the original French) - to his kingdom.

One day, the new King must go to war against his neighbor, Emperor Contalabutte, and leaves his mother to govern the kingdom and look after his family. After her son leaves, the Ogress Queen Mother sends her daughter-in-law to a house secluded in the woods and orders her cook to prepare Morning with Sauce Robert for dinner. The kind-hearted cook substitutes a lamb for the princess, which satisfies the Queen Mother. She then demands Day, but the cook this time substitutes a kid for the prince, which also satisfies the Queen Mother. When the Ogress demands that he serve up the Sleeping Beauty, the latter substitutes a hind prepared with Sauce Robert, satisfying the Ogress, and secretly reuniting the young Queen with her children, who have been hidden by the cook's wife and maid. However, the Queen Mother soon discovers the cook's trick and she prepares a tub in the courtyard filled with vipers and other noxious creatures. The King returns home unexpectedly and the Ogress, her true nature having been exposed, throws herself into the tub and is fully consumed by the creatures. The King, young Queen, and children then live happily ever after.

Brothers Grimm's version

[edit]

The Brothers Grimm included a variant of Sleeping Beauty, Little Briar Rose, in the first volume of Children's and Household Tales (published 1812).[23] Their version ends when the prince arrives to wake Sleeping Beauty (named Rosamund) with a kiss and does not include the part two as found in Basile's and Perrault's versions.[24] The brothers considered rejecting the story on the grounds that it was derived from Perrault's version, but the presence of the Brynhild tale convinced them to include it as an authentically German tale. Their decision was notable because in none of the Teutonic myths, meaning the Poetic and Prose Eddas or Volsunga Saga, are their sleepers awakened with a kiss, a fact Jacob Grimm would have known since he wrote an encyclopedic volume on German mythology. His version is the only known German variant of the tale, and Perrault's influence is almost certain.[25] In the original Brothers Grimm's version, the fairies are instead wise women.[26]

The Brothers Grimm also included, in the first edition of their tales, a fragmentary fairy tale, "The Evil Mother-in-law". This story begins with the heroine, a married mother of two children, and her mother-in-law, who attempts to eat her and the children. The heroine suggests an animal be substituted in the dish, and the story ends with the heroine's worry that she cannot keep her children from crying and getting the mother-in-law's attention. Like many German tales showing French influence, it appeared in no subsequent edition.[27]

Variations

[edit]

The princess's name has varied from one adaptation to the other. In Sun, Moon, and Talia, she is named Talia (Sun and Moon being her twin children). She has no name in Perrault's story but her daughter is called "Aurore". The Brothers Grimm named her "Briar Rose" in their first collection.[23] However, some translations of the Grimms' tale give the princess the name "Rosamond". Tchaikovsky's ballet and Disney's version named her Princess Aurora; however, in the Disney version, she is also called "Briar Rose" in her childhood, when she is being raised incognito by the good fairies.[28]

Besides Sun, Moon, and Talia, Basile included another variant of this Aarne-Thompson type, The Young Slave, in his book, The Pentamerone. The Grimms also included a second, more distantly related one titled The Glass Coffin.[29]

Italo Calvino included a variant in Italian Folktales, Sleeping Beauty and Her Children. In his version, the cause of the princess's sleep is a wish by her mother. As in Pentamerone, the prince rapes her in her sleep and her children are born. Calvino retains the element that the woman who tries to kill the children is the king's mother, not his wife, but adds that she does not want to eat them herself, and instead serves them to the king. His version came from Calabria, but he noted that all Italian versions closely followed Basile's.[30][31]

In his More English Fairy Tales, Joseph Jacobs noted that the figure of the Sleeping Beauty was in common between this tale and the Romani tale The King of England and his Three Sons.[32]

The hostility of the king's mother to his new bride is repeated in the fairy tale The Six Swans,[33] and also features in The Twelve Wild Ducks, where the mother is modified to be the king's stepmother. However, these tales omit the attempted cannibalism.

Russian Romantic writer Vasily Zhukovsky wrote a versified work based on the theme of the princess cursed into a long sleep in his poem "Спящая царевна" ("The Sleeping Tsarevna"), published in 1832.[34]

Interpretations

[edit]

According to Maria Tatar, the Sleeping Beauty tale has been disparaged by modern-day feminists who consider the protagonist to have no agency and find her passivity to be offensive; some feminists have even argued for people to stop telling the story altogether.[35]

Disney has received criticism for depicting both Cinderella and the Sleeping Beauty princess as "naïve and malleable" characters.[36] Time Out dismissed the princess as a "delicate" and "vapid" character.[37] Sonia Saraiya of Jezebel echoed this sentiment, criticizing the princess for lacking "interesting qualities", where she also ranked her as Disney's least feminist princess.[38] Similarly, Bustle also ranked the princess as the least feminist Disney Princess, with author Chelsea Mize expounding, "Aurora literally sleeps for like three quarters of the movie … Aurora just straight-up has no agency, and really isn't doing much in the way of feminine progress."[39] Leigh Butler of Tor.com went on to defend the character writing, "Aurora’s cipher-ness in Sleeping Beauty would be infuriating if she were the only female character in it, but the presence of the Fairies and Maleficent allow her to be what she is without it being a subconscious statement on what all women are."[40] Similarly, Refinery29 ranked Princess Aurora the fourth most feminist Disney Princess because, "Her aunts have essentially raised her in a place where women run the game."[41] Despite being featured prominently in Disney merchandise, "Aurora has become an oft-forgotten princess", and her popularity pales in comparison to those of Cinderella and Snow White.[42]

An example of the cosmic interpretation of the tale given by the nineteenth century solar mythologist school[43] appears in John Fiske's Myths and Myth-Makers: “It is perhaps less obvious that winter should be so frequently symbolized as a thorn or sharp instrument ... Sigurd is slain by a thorn, and Balder by a sharp sprig of mistletoe; and in the myth of the Sleeping Beauty, the earth-goddess sinks into her long winter sleep when pricked by the point of the spindle. In her cosmic palace, all is locked in icy repose, naught thriving save the ivy which defies the cold, until the kiss of the golden-haired sun-god reawakens life and activity.”[44]

Media

[edit]"Sleeping Beauty" has been popular for many fairytale fantasy retellings. Some examples are listed below:

In film and television

[edit]- La belle au Bois-Dormant (1902), a French silent film directed by Lucien Nonguet and Ferdinand Zecca.[45]

- La Belle au bois dormant (1908), a French silent film directed by Lucien Nonguet and Albert Capellani.[46]

- Dornröschen (1917), a German silent film directed by Paul Leni.[47]

- Dornröschen (1929), a German silent film directed by Dorothy Douglas.[48]

- Dornröschen (1936), a German film directed by Alf Zengerling.[48]

- Dornröschen (1941), a German stop-motion short directed by Ferdinand Diehl.[48][49]

- The Sleeping Princess (1939), a Walter Lantz Productions animated short parodying the original fairy tale.[50]

- A loose adaptation can be seen in a scene from the propaganda cartoon Education for Death, where Sleeping Beauty is a valkyrie representing Nazi Germany, and where the prince is replaced with Fuehrer Adolf Hitler in knights' armor. The short also parodies Richard Wagner's opera Siegfried.

- Prinsessa Ruusunen (1949), a Finnish film directed by Edvin Laine and scored with Erkki Melartin's incidental music from 1912.[51]

- Dornröschen (1955), a West German film directed by Fritz Genschow.[52]

- Shirley Temple's Storybook (1958), episode The Sleeping Beauty, directed by Mitchell Leisen and starring Anne Helm, Judith Evelyn and Alexander Scourby.

- Sleeping Beauty (1959), a Walt Disney animated film based on both Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm's versions. Featuring the original voices of Mary Costa as Princess Aurora, the Sleeping Beauty and Eleanor Audley as Maleficent.[53]

- Sleeping Beauty (Спящая красавица [Spjáščaja krasávica]) (1964), a filmed version of the ballet produced by the Kirov Ballet along with Lenfilm studios, starring Alla Sizova as Princess Aurora.[54]

- Dornröschen (1971), an East German film directed by Walter Beck.[55]

- Festival of Family Classics (1972–73), episode Sleeping Beauty, produced by Rankin/Bass and animated by Mushi Production.[56]

- Some Call It Loving (also known as Sleeping Beauty) (1973), directed by James B. Harris and starring Zalman King, Carol White, Tisa Farrow, and Richard Pryor, based on a short story by John Collier.[57]

- Manga Fairy Tales of the World (1976–79), 10-minute adaptation.

- Jak se budí princezny (1978), a Czechoslovakian film directed by Václav Vorlíček.[58]

- World Famous Fairy Tale Series (Sekai meisaku dōwa) (1975–83) has a 9-minute adaptation, later reused in the U.S. edit of My Favorite Fairy Tales.

- Faerie Tale Theatre (1983), episode Sleeping Beauty, directed by Jeremy Kagan and starring Christopher Reeve, Bernadette Peters and Beverly D'Angelo.

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears/Rumpelstiltskin/Little Red Riding Hood/Sleeping Beauty (1984), direct-to-video featurette by Lee Mendelson Film Productions.[59]

- A 1986 episode of Brummkreisel had Kunibert (Hans-Joachim Leschnitz) demanding that he and his friends Achim (Joachim Kaps), Hops and Mops enact the story of Sleeping Beauty. Achim first compromises by incorporating Sleeping Beauty into his lesson about days of the week, and then finally he allows Kunibert to have his way; Hops played the princess, Kunibert played the prince, Mops played the wicked fairy and Achim played the brambles.

- Sleeping Beauty (1987), a direct-to-television musical film directed by David Irving.[60]

- An episode of the series Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics (1987–89) is dedicated to Princess Briar Rose.[61]

- The Legend of Sleeping Brittany (1989), an episode of Alvin & the Chipmunks based on the fairy tale.[62]

- Briar-Rose or The Sleeping Beauty (1990), a Japanese/Czechoslovakian stop-motion animated featurette directed by Kihachiro Kawamoto.

- Britannica's Tales Around the World (1990–91), features three variations of the story.[63]

- Sleeping Beauty (1991), a direct-to-video animated featurette produced by American Film Investment Corporation.[64]

- World Fairy Tale Series (Anime sekai no dōwa) (1995), anime television anthology produced by Toei Animation, has half-hour adaptation.

- Sleeping Beauty (1995), a Japanese-American direct-to-video animated film by Jetlag Productions.[65]

- Wolves, Witches and Giants (1995–99), episode Sleeping Beauty, season 1 episode 12.

- Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child (1995), episode Sleeping Beauty, the classic story is told with a Hispanic cast, when Rosita is cast into a long sleep by Evelina, and later awakened by Prince Luis.[66]

- The Legend of Sleeping Beauty (La leggenda della bella addormentata) (1998), an Italian television series of 26 episodes, distributed by Mondo tv.

- The Triplets (Les tres bessones/Las tres mellizas) (1997–2003), catalan animated series, season 1 episode 19.

- Simsala Grimm (1999–2010), episode 9 of season 2.

- Bellas durmientes (Sleeping Beauties) (2001), directed by Eloy Lozano, adapted from the Kawabata novel.[67]

- Hello Kitty's Animation Theater (2001), features a 16-minute adaptation.

- Shrek the third (2007) a Dreamworks animated film, directed by Chris Miller.[68]

- Dornröschen (2009), a German made-for-television film directed by Oliver Dieckmann starring Lotte Flack, François Goeske and Hannelore Elsner.

- La belle endormie (The Sleeping Beauty) (2010), a film by Catherine Breillat.[69]

- Sleeping Beauty (2011), directed by Julia Leigh and starring Emily Browning, about a young girl who takes a sleeping potion and lets men have their way with her to earn extra money.[70]

- Once Upon a Time (2011), an ABC TV show with Sarah Bolger as Aurora and Julian Morris as Philip.[71]

- Sleeping Beauty (2014), a film by Rene Perez.[72]

- Sleeping Beauty (2014), a film by Casper Van Dien.[73]

- Maleficent (2014), a live-action reimagining of the Walt Disney movie starring Angelina Jolie as Maleficent and Elle Fanning as Princess Aurora.[74]

- Ever After High, episode Briar Beauty (2015), an animated Netflix series.[75]

- The Curse of Sleeping Beauty (2016), an American horror film directed by Pearry Reginald Teo.[76]

- Archie Campbell satirized the story with "Beeping Sleauty" in several Hee Haw television episodes.

- Maleficent: Mistress of Evil (2019), the sequel to Maleficent (2014).[77]

- Avengers Grimm (2015) portrays an adult Sleeping Beauty with superpowers.

- Sleeping Beauty is a main character of the "Neverafter" season of the tabletop role-playing game show Dimension 20. She is played by Siobhan Thompson. In this adaptation, she goes by the name Rosamund du Prix (2022–2023).

- Awakening Sleeping Beauty (2025), an upcoming horror re-telling of the story set in The Twisted Childhood Universe, directed by Louisa Warren and starring Lora Hristova, Robbie Taylor and Charlotte Coleman as Princess Thalia, the Prince and Queen Primrose, respectively, along with Lila Lasso, Leah Glater, Sophie Rankin, Judy Tcherniak and Danielle Scott.

In literature

[edit]

- Sleeping Beauty (1830) and The Day-Dream (1842), two poems based on Sleeping Beauty by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.[78]

- The Rose and the Ring (1854), a satirical fantasy by William Makepeace Thackeray.

- The Sleeping Beauty (1919), a poem by Mary Carolyn Davies about a failed hero who did not waken the princess, but died in the enchanted briars surrounding her palace.[79]

- The Sleeping Beauty (1920), a retelling of the fairy tale by Charles Evans, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham.[80]

- Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty) (1971), a poem by Anne Sexton in her collection Transformations (1971), in which she re-envisions sixteen of the Grimm's Fairy Tales.[81]

- The Sleeping Beauty Quartet (1983–2015), four erotic novels written by Anne Rice under the pen name A.N. Roquelaure, set in a medieval fantasy world and loosely based on the fairy tale.[82]

- Beauty (1992), a novel by Sheri S. Tepper.[83]

- Briar Rose (1992), a novel by Jane Yolen.[84]

- Enchantment (1999), a novel by Orson Scott Card based on the Russian version of Sleeping Beauty.

- Spindle's End (2000), a novel by Robin McKinley.[85]

- Clementine (2001), a novel by Sophie Masson.[86]

- Waking Rose (2007), novel by Regina Doman.

- A Kiss in Time (2009), a novel by Alex Flinn.[87]

- The Sleeper and the Spindle (2012), a novel by Neil Gaiman.[88]

- The Gates of Sleep (2012), a novel by Mercedes Lackey from the Elemental Masters series set in Edwardian England.[89]

- Sleeping Beauty: The One Who Took the Really Long Nap (2018), a novel by Wendy Mass and the second book in the Twice Upon a Time series features a princess named Rose who pricks her finger and falls asleep for 100 years.[90]

- The Sleepless Beauty (2019), a novel by Rajesh Talwar setting the story in a small kingdom in the Himalayas.[91]

- Lava Red Feather Blue (2021), a novel by Molly Ringle involving a male/male twist on the Sleeping Beauty story.

- Malice (2021), a novel by Heather Walter told by the Maleficent character's (Alyce's) POV and involving a woman/woman love story. [92]

- Misrule (2022), a novel by Heather Walter and sequel to Malice. [93]

- Immortality, a poem by Lisel Mueller in her Pulitzer Prize winning book "Alive Together"

In music

[edit]

- La Belle au Bois Dormant (1825), an opera by Michele Carafa.

- La belle au bois dormant (1829), a ballet in four acts with book by Eugène Scribe, composed by Ferdinand Hérold and choreographed by Jean-Louis Aumer.

- The Sleeping Beauty (1890), a ballet by Tchaikovsky.

- Dornröschen (1902), an opera by Engelbert Humperdinck.

- Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (1910), the first movement of Ravel's Ma mère l'Oye.[94]

- The Sleeping Beauty (1992), song on album Clouds by the Swedish band Tiamat.

- Sleeping Beauty Wakes (2008), an album by the American musical trio GrooveLily.[95]

- There Was A Princess Long Ago, a common nursery rhyme or singing game typically sung stood in a circle with actions, retells the story of Sleeping Beauty in a summarised song.[96]

- Sleeping Beauty The Musical (2019), a two act musical with book and lyrics by Ian Curran and music by Simon Hanson and Peter Vint.[97]

- Hex (2021) is a musical with book by Tanya Ronder, music by Jim Fortune and lyrics by Rufus Norris that opened at the Royal National Theatre in December 2021.

In video games

[edit]- Kingdom Hearts is a video game in which Maleficent is one of the main antagonists and Aurora is one of the Princesses of Heart together with the other Disney princesses.

- Little Briar Rose (2019) is a point-and-click adventure inspired by the Brothers Grimm's version of the fairy tale.[98]

- SINoALICE (2017) is a mobile gacha game which features Sleeping Beauty as one of the main player characters. She has her own dark story-line which follows her unending desire to sleep, and crosses over with the other fairy-tale characters featured in the game.

- Video game series Dark Parables adapted the tale as the plot of its first game, Curse of Briar Rose (2010).

In art

[edit]-

Perrault's La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), illustration by Gustave Doré

-

Sleeping Beauty by Jenny Harbour

-

Book cover for a Dutch interpretation of the story by Johann Georg van Caspel

-

Briar Rose

-

Sleeping Beauty by Edward Frederick Brewtnall

-

Louis Sußmann-Hellborn (1828- 1908) Sleeping Beauty,

-

Sleeping Princess by Viktor Vasnetsov

-

Sleeping Beauty, statue in Wuppertal – Germany

See also

[edit]- The Glass Coffin

- Princess Aubergine

- Rip Van Winkle

- Snow White

- The Sleeping Prince (fairy tale)

- Sleeping Beauty problem, a mathematical puzzle based on the fairy tale

Notes

[edit]- ^ Literally, 'the beauty[,] in the wood[,] sleeping', where the present participle "sleeping" (dormant) refers to the beauty, not to the wood.[2] In modern French, the title would be rendered as "La Belle dormant au bois". The positioning of present participles after their complements was frequent in Old French[3] but is nowadays considered archaic (although it is still used in a number of set phrases such as chemin faisant and tambour battant), and the title has been misinterpreted as meaning "the beauty in the sleeping wood" as a result.[4] It is also dormant and not dormante because present participles have been invariable in French since a decision of 3 June 1679 of the Académie Française (of which Charles Perrault was a member).[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Anita Moss (1986). The Family of Stories: An Anthology of Children's Literature. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-03-921832-4.

- ^ F. P. Terzuolo (1864). Études sur le Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française (in French). p. 62.

[...] exactement comme on dit : La Belle au bois dormant, ce qui ne veut pas dire la belle au bois qui dort, mais la belle qui dort au bois [...]

- ^ Léopold Constans (1890). Chrestomathie de l'ancien français (IXe-XVe siècles) (in French). p. 15.

- ^ Linguist. Vol. 13. 1951. p. 92.

- ^ Larive & Fleury (1888). La troisième année de grammaire (in French). p. 148.

- ^ "410: The Sleeping Beauty". Multilingual Folk Tale Database. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jorg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. pp. 244–245.

- ^ Zago, Ester (1991). ""Frayre de Joy e Sor de Plaser" Re-Examined". Merveilles & Contes. 5 (1): 68–73. JSTOR 41390275.

- ^ a b Hallett, Martin; Karasek, Barbara, eds. (2009). Folk & Fairy Tales (4 ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-1-55111-898-7.

- ^ Bottigheimer, Ruth. (2008). "Before Contes du temps passe (1697): Charles Perrault's Griselidis, Souhaits and Peau". The Romantic Review, Volume 99, Number 3. pp. 175–189.

- ^ "The Original Sleeping Beauty: A Journey Through the Dark Roots of a Beloved Tale - Magical Clan". 14 November 2023.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. pp. 137–138.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 648, ISBN 0-393-97636-X.

- ^ Camarena, Julio. Cuentos tradicionales de León. Vol. I. Tradiciones orales leonesas, 3. Madrid: Seminario Menéndez Pidal, Universidad Complutense de Madrid; [León]: Diputación Provincial de León, 1991. p. 415.

- ^ Frayre de Joy e Sor de Plaser.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Charles Willing, "Genevieve of Brabant"

- ^ a b Basile, Giambattista. "Sun, Moon, and Talia". Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Collis, Kathryn (2016). Not So Grimm Fairy Tales. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5144-4689-8.

- ^ a b Maria Tatar, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, 2002:96, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Ashliman, D.L. "Sleeping Beauty". pitt.edu.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty".

- ^ a b Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm (1884) [1812]. Grimm's Household Tales: With the Author's Notes. Vol. 1. Translated by Hunt, Margaret. Introduction by Andrew Lang. London: George Bell & Sons. pp. iii, 197–200. OL 45361W.

- ^ Harry Velten, "The Influences of Charles Perrault's Contes de ma Mère L'oie on German Folklore", p 961, Jack Zipes, ed. The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Harry Velten, "The Influences of Charles Perrault's Contes de ma Mère L'oie on German Folklore", p 962, Jack Zipes, ed. The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ "050 Sleeping Beauty – Great Story Reading Project".

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 376-7 W. W. Norton & Company, London, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, "The Annotated Sleeping Beauty Archived 2010-02-22 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, "Tales Similar to Sleeping Beauty" Archived 2010-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 485 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 744 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, More English Fairy Tales, "The King of England and his Three Sons" Archived 2010-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 230 W. W. Norton & company, London, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Zhukovsky, Vasily. (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Tatar, Maria (2014). "Show and Tell: Sleeping Beauty as Verbal Icon and Seductive Story". Marvels & Tales. 28 (1): 142–158. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.1.0142. S2CID 161271883.

- ^ Hugel, Melissa (November 12, 2013). "How Disney Princesses Went From Passive Damsels to Active Heroes". Mic. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty". Time Out. 26 May 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Saraiya, Sonia (December 7, 2012). "A Feminist Guide to Disney Princesses". Jezebel. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Mize, Chelsea (July 31, 2015). "A Feminist Ranking Of All The Disney Princesses, Because Not Every Princess Was Down For Waiting For Anyone To Rescue Her". Bustle. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Butler, Leigh (November 6, 2014). "How Sleeping Beauty is Accidentally the Most Feminist Animated Movie Disney Ever Made". Tor.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Golembewski, Vanessa (September 11, 2014). "A Definitive Ranking Of Disney Princesses As Feminist Role Models". Refinery29. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ "The Evolution of Disney Princesses". Young Writers Society. March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. (1955). "The Eclipse of Solar Mythology". The Journal of American Folklore. 68 (270): 393–416. doi:10.2307/536766. JSTOR 536766.

- ^ "Myths and Myth-makers, by John Fiske".

- ^ Nonguet, Lucien; Zecca, Ferdinand (1903-07-11), La belle au bois dormant (Fantasy, Short, Drama), Pathé Frères, retrieved 2023-12-27

- ^ Capellani, Albert; Nonguet, Lucien (1908-04-05), La belle au bois dormant (Short, Fantasy), Julienne Mathieu, Pathé Frères, retrieved 2023-12-27

- ^ Leni, Paul (1917-12-20), Dornröschen (Family, Fantasy), Mabel Kaul, Harry Liedtke, Käthe Dorsch, Union-Film, retrieved 2023-12-27

- ^ a b c "Märchenhafte Drehorte: Wo Dornröschen wach geküsst wird - Märchen im Film" (in German). 2020-02-29. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

- ^ Diehl, Ferdinand, Dornröschen (Animation, Short), retrieved 2023-12-27

- ^ "The Sleeping Princess (1939)". IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (1949) Prinsessa Ruusunen (original title)". IMDb. 8 April 1949. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (1955) Dornröschen (original title)". IMDb. 16 November 1955. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (1959)". IMDb. 30 October 1959. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Dudko, Apollinari; Sergeyev, Konstantin, Spyashchaya krasavitsa (Fantasy, Music, Romance), Lenfilm Studio, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ Beck, Walter (1971-03-26), Dornröschen (Family, Fantasy), Juliane Korén, Vera Oelschlegel, Helmut Schreiber, Deutsche Film (DEFA), retrieved 2023-12-24

- ^ Bass, Jules; Rankin, Arthur Jr. (1973-01-21), Sleeping Beauty, Festival of Family Classics, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ "Some Call It Loving (1973)". IMDb. 26 October 1973. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Vorlícek, Václav (1978-03-01), Jak se budí princezny (Adventure, Comedy, Family), Deutsche Film (DEFA), Filmové studio Barrandov, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ Melendez, Steven Cuitlahuac, Goldilocks and the Three Bears/Rumpelstiltskin/Little Red Riding Hood/Sleeping Beauty (Animation, Short), On Gossamer Wings Productions, Bill Melendez Productions, retrieved 2022-06-29

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (1987)". IMDb. 12 June 1987. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Nobara hime, Grimm Masterpiece Theatre, 1988-02-17, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ "Inner Dave/The Legend of Sleeping Brittany". IMDb. 11 November 1989. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Britannica's Tales Around the World (Animation), Encyclopædia Britannica Films, retrieved 2022-06-29

- ^ Simon, Jim (2000-04-11), Sleeping Beauty (Animation, Short, Family), Golden Films, retrieved 2023-12-28

- ^ Hiruma, Toshiyuki; Takashi (1995-03-17), Sleeping Beauty (Animation, Family, Fantasy), Cayre Brothers, Jetlag Productions, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty". IMDb. 23 April 1995. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauties (2001) Bellas durmientes (original title)". IMDb. 9 November 2001. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Shrek the Third (2007) - IMDb, retrieved 2023-05-03

- ^ "The Sleeping Beauty (2010) La belle endormie (original title)". IMDb. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (2011)". IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Once Upon a Time". IMDb. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (2014)". IMDb. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty (2014)". IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Maleficent (2014)". IMDb. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Ever After High". IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "The Curse of Sleeping Beauty (2016)". IMDb. 2 June 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Maleficent: Mistress of Evil (2019)". IMDb. 20 Oct 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Hill, Robert (1971), Tennyson's Poetry p. 544. New York: Norton.

- ^ Cook, Howard Willard Our Poets of Today, p. 271, at Google Books

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty, The". David Brass Rare Books. Retrieved 15 April 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Transformations by Anne Sexton"

- ^ "The Sleeping Beauty Series". Anne Rice. 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Tepper, Sheri S. (1992). Beauty. Random House Worlds. ISBN 9780553295276. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Briar Rose". Jane Yolen. 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Spindle's End". Penguin Random House Network.

- ^ Clementine. ASIN 0340850698.

- ^ Flinn, Alex (28 April 2009). A Kiss in Time. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060874193.

- ^ "The Sleeper and the Spindle". Neil Gaiman. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ The Gates of Sleep (Elemental Masters Book 2). 4 March 2003. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Sleeping Beauty, the One Who Took the Really Long Nap: A Wish Novel (Twice Upon a Time #2): A Wish Novel. ASIN 043979658X.

- ^ "The Sleepless Beauty".

- ^ "Malice".

- ^ "Misrule".

- ^ "Ravel : Ma Mère l'Oye". genedelisa.com.

- ^ "Sleeping Beauty Wakes". bandcamp. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "There Was A Princess". singalong.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ "2019 musical website". Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Little Briar Rose". Nintendo. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Artal, Susana. "Bellas durmientes en el siglo XIV". In: Montevideana 10. Universidad de la Republica, Linardi y Risso. 2019. pp. 321–336.

- Yokomichi, Makoto (2012). "Eine Ubersicht der Auffassungen zur Herkunft des Typs ATU 410 (KHM50) : Germanische, romanische und andere Theorien in den Anmerkungen der Bruder Grimm sowie Boltes/Polivkas, im AaTh/ATU-Verzeichnis, HdM- und EM-Artikeln (Teil 2)". The Scientific Reports of Kyoto Prefectural University. Humanities (in German). 64: 23–40.

- Starostina, Aglaia. "Chinese Medieval Versions of Sleeping Beauty". In: Fabula, vol. 52, no. 3-4, 2012, pp. 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabula-2011-0017

- de Vries, Jan. "Dornröschen". In: Fabula 2, no. 1 (1959): 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1959.2.1.110

External links

[edit]- The complete set of Grimms' Fairy Tales, including Sleeping Beauty at Standard Ebooks

- Sleeping beauty in the woods, by Perrault, 1870 illustrated scanned book via Internet Archive

- The Stalk of Flax adapted by Amy Friedman and Meredith Johnson Archived 2018-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Illustrations of the fairy tale

The Sleeping Beauty. A painting by John Wood, engraved by F. Bacon and with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in the Forget Me Not annual, 1837.

The Sleeping Beauty. A painting by John Wood, engraved by F. Bacon and with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in the Forget Me Not annual, 1837. Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Sleeping Beauty

- 14th-century literature

- Grimms' Fairy Tales

- Female characters in fairy tales

- European fairy tales

- Fairies in popular culture

- French fairy tales

- Fictional princesses

- Witchcraft in fairy tales

- Works by Charles Perrault

- European folklore characters

- Textiles in folklore

- Fiction about rape

- Fiction about curses

- Sleep in mythology and folklore

- Fiction about uxoricide

- Works about princesses

- ATU 400-459

- Brunhild

- Works about kissing