History of espionage

Spying, as well as other intelligence assessment, has existed since ancient history. In the 1980s scholars characterized foreign intelligence as "the missing dimension" of historical scholarship."[1] Since then a largely popular and scholarly literature has emerged.[2] Special attention has been paid to World War II,[3] as well as the Cold War era (1947–1989) that was a favorite for novelists and filmmakers.[4]

Early history

[edit]

Efforts to use espionage for military advantage are well documented throughout history. Sun Tzu, 4th century BC, a theorist in ancient China who influenced Asian military thinking, still has an audience in the 21st century for the Art of War. He advised, "One who knows the enemy and knows himself will not be endangered in a hundred engagements."[5] He stressed the need to understand yourself and your enemy for military intelligence. He identified different spy roles. In modern terms, they included the secret informant or agent in place, (who provides copies of enemy secrets), the penetration agent (who has access to the enemy's commanders), and the disinformation agent (who feeds a mix of true and false details to point the enemy in the wrong direction to confuse the enemy). He considered the need for systematic organization and noted the roles of counterintelligence, double agents (recruited from the ranks of enemy spies), and psychological warfare. Sun Tzu continued to influence Chinese espionage theory in the 21st century with its emphasis on using the information to design active subversion.[6]

Chanakya (also called Kautilya) wrote his Arthashastra in India in the 4th century BC. It was a 'Textbook of Statecraft and Political Economy' that provides a detailed account of intelligence collection, processing, consumption, and covert operations, as indispensable means for maintaining and expanding the security and power of the state.[7]

Ancient Egypt had a thoroughly developed system for the acquisition of intelligence. The Hebrews used spies as well, as in the story of Rahab. Thanks to the Bible (Joshua 2:1–24) we have in this story of the spies sent by Ancient Hebrews to Jericho before attacking the city one of the earliest detailed reports of a very sophisticated intelligence operation[8]

Spies were also prevalent in the Greek and Roman empires.[9] During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Mongols relied heavily on espionage in their conquests in Asia and Europe. Feudal Japan often used shinobi to gather intelligence.

A significant milestone was the establishment of an effective intelligence service under King David IV of Georgia at the beginning of the 12th century or possibly even earlier. Called mstovaris, these organized spies performed crucial tasks, like uncovering feudal conspiracies, conducting counter-intelligence against enemy spies, and infiltrating key locations, e.g. castles, fortresses and palaces.[10]

Aztecs used Pochtecas, people in charge of commerce, as spies and diplomats, and had diplomatic immunity. Along with the pochteca, before a battle or war, secret agents, quimitchin, were sent to spy amongst enemies usually wearing the local costume and speaking the local language, techniques similar to modern secret agents.[11]

Early modern Europe

[edit]Many modern espionage methods were established by Francis Walsingham in Elizabethan England. His staff included the cryptographer Thomas Phelippes, who was an expert in deciphering letters and forgery, and Arthur Gregory, who was skilled at breaking and repairing seals without detection.[12][13] The Catholic exiles fought back when the Welsh exile Hugh Owen created an intelligence service that tried to neutralize that of Walsingham.[14]

In 1585, Mary, Queen of Scots was placed in the custody of Sir Amias Paulet, who was instructed to open and read all of Mary's clandestine correspondence. In a successful attempt to expose her, Walsingham arranged a single exception: a covert means for Mary's letters to be smuggled in and out of Chartley in a beer keg. Mary was misled into thinking these secret letters were secure, while in reality they were deciphered and read by Walsingham's agents. He succeeded in intercepting letters that indicated a conspiracy to displace Elizabeth I with Mary. In foreign intelligence, Walsingham's extensive network of "intelligencers", who passed on general news as well as secrets, spanned Europe and the Mediterranean. While foreign intelligence was a normal part of the principal secretary's activities, Walsingham brought to it flair and ambition, and large sums of his own money. He cast his net more widely than anyone had attempted before, exploiting links across the continent as well as in Constantinople and Algiers, and building and inserting contacts among Catholic exiles.[13][15]

18th century

[edit]The 18th century saw a dramatic expansion of espionage activities.[16] It was a time of war: in nine years out of 10, two or more major powers were at war. Armies grew much larger, with corresponding budgets. Likewise the foreign ministries all grew in size and complexity. National budgets expanded to pay for these expansions, and room was found for intelligence departments with full-time staffs, and well-paid spies and agents. The militaries themselves became more bureaucratised, and sent out military attaches. They were very bright, personable middle-ranking officers stationed in embassies abroad. In each capital, the attached diplomats evaluated the strength, capabilities, and war plans of the armies and navies.[17]

France

[edit]The Kingdom of France under King Louis XIV (1643–1715) was the largest, richest, and most powerful nation. It had many enemies and a few friends, and tried to keep track of them all through a well organized intelligence system based in major cities all over Europe. France and England pioneered the cabinet noir whereby foreign correspondence was opened and deciphered, then forwarded to the recipient. France's chief ministers, especially Cardinal Mazarin (1642–1661) did not invent the new methods; they combined the best practices from other states, and supported it at the highest political and financial levels.[18][19]

To critics of authoritarian governments, it appeared that spies were everywhere. Parisian dissidents of the 18th century thought that they were surrounded by as many as perhaps 30,000 police spies. However, the police records indicate a maximum of 300 paid informers. The myth was deliberately designed to inspire fear and hypercaution; the police wanted people to think that they were under close watch. The critics also seemed to like the myth, for it gave them a sense of importance and an aura of mystery. Ordinary Parisians felt more secure believing that the police were actively dealing with troublemakers.[20]

British

[edit]To deal with the almost continuous wars with France, London set up an elaborate system to gather intelligence on France and other powers. Since the British had deciphered the code system of most states, it relied heavily on intercepted mail and dispatches. A few agents in the postal system could intercept likely correspondence and have it copied and forwarded to the intended receiver, as well as to London. Active spies were also used, especially to estimate military and naval strength and activities. Once the information was in hand, analysts tried to interpret diplomatic policies and intentions of states. Of special concern in the first half of the century were the activities of Jacobites, English supporters of the House of Stuart who had French support in plotting to overthrow the Hanoverian dynasty in England. It was a high priority to find men in England and Scotland who had secret Jacobite sympathies.[21]

One highly successful operation took place in the Russian Empire under the supervision of minister Charles Whitworth (1704 to 1712). He closely observed public events and noted the changing power status of key leaders. He cultivated influential and knowledgeable persons at the royal court, and befriended foreigners in Russia's service, and in turn they provided insights into high-level Russian planning and personalities, which he summarized and sent in code to London.[22]

Industrial espionage

[edit]In 1719 Britain made it illegal to entice skilled workers to emigrate. Nevertheless, small-scale efforts continued in secret. At mid century, (1740s to 1770s) the French Bureau of Commerce had a budget and a plan, and systematically hired British and French spies to obtain industrial and military technology. They had some success deciphering English technology regarding plate-glass, the hardware and steel industry. They had mixed success, enticing some workers and getting foiled in other attempts.[23][24]

The Spanish were technological laggards, and tried to jump start industry through systematized industrial espionage. The Marquis of Ensenada, a minister of the king, sent trusted military officers on a series of missions between 1748 and 1760. They focused on current technology regarding shipbuilding, steam engines, copper refining, canals, metallurgy, and cannon-making.[25]

American Revolution, 1775–1783

[edit]During the American Revolution, 1775–1783, American General George Washington developed a successful espionage system to detect British locations and plans. In 1778, he ordered Major Benjamin Tallmadge to form the Culper Ring to collect information about the British in New York.[26] Washington was usually mindful of treachery, but he ignored incidents of disloyalty by Benedict Arnold, his most trusted general. Arnold tried to betray West Point to the British Army, but was discovered and barely managed to escape.[27] The British intelligence system was weak; it completely missed the movement of the entire American and French armies from the Northeast to Yorktown, Virginia, where they captured the British invasion army in 1781 and won independence.[28] Washington has been called "Americas First Spymaster".[29]

French Revolution and Napoleonic wars, (1793–1815)

[edit]The Kingdom of Great Britain, almost continuously at war with France (1793–1815), built a wide network of agents and funded local elements trying to overthrow governments hostile to Britain.[30][31] It paid special attention to threats of an invasion of the British Isles, and to a possible uprising in Ireland.[32] Britain in 1794 appointed William Wickham as Superintendent of Aliens in charge of espionage and the new secret service. He strengthened the British intelligence system by emphasizing the centrality of the intelligence cycle – query, collection, collation, analysis and dissemination – and the need for an all-source centre of intelligence.[33][34] Even so, Britain reduced its clandestine operations following the 1802 Treaty of Amiens as it emphasized the development of commercial relations with the Continent and some members of Parliament questioned the use of secret service funds.[35]

Napoleon made heavy use of agents, especially regarding Russia. Besides espionage, they recruited soldiers, collected money, enforced the Continental System against imports from Britain, propagandized, policed border entry into France through passports, and protected the estates of the Napoleonic nobility. His senior men coordinated the policies of satellite countries.[36]

19th century

[edit]

Modern tactics of espionage and dedicated government intelligence agencies were developed over the course of the late 19th century. A key background to this development was the Great Game, a period denoting the strategic rivalry and conflict that existed between the British Empire and the Russian Empire throughout Central Asia. To counter Russian ambitions in the region and the potential threat it posed to the British position in India, a system of surveillance, intelligence and counterintelligence was built up in the Indian Civil Service. The existence of this shadowy conflict was popularised in Rudyard Kipling's famous spy book, Kim, where he portrayed the Great Game (a phrase he popularised) as an espionage and intelligence conflict that "never ceases, day or night."

Although the techniques originally used were distinctly amateurish – British agents would often pose unconvincingly as botanists or archaeologists – more professional tactics and systems were slowly put in place. In many respects, it was here that a modern intelligence apparatus with permanent bureaucracies for internal and foreign infiltration and espionage was first developed. A pioneering cryptographic unit was established as early as 1844 in India, which achieved some important successes in decrypting Russian communications in the area.[37]

The establishment of dedicated intelligence organizations was directly linked to the colonial rivalries between the major European powers and the accelerating development of military technology.

An early source of military intelligence was the diplomatic system of military attachés (an officer attached to the diplomatic service operating through the embassy in a foreign country), that became widespread in Europe after the Crimean War. Although officially restricted to a role of transmitting openly received information, they were soon being used to clandestinely gather confidential information and in some cases even to recruit spies and to operate de facto spy rings.

American Civil War 1861–1865

[edit]Tactical or battlefield intelligence became very vital to both armies in the field during the American Civil War. Allan Pinkerton, who operated a pioneer detective agency, served as head of the Union Intelligence Service during the first two years. He thwarted the assassination plot in Baltimore while guarding President-elect Abraham Lincoln. Pinkerton agents often worked undercover as Confederate States Army soldiers and sympathizers to gather military intelligence. Pinkerton himself served on several undercover missions. He worked across the Deep South in the summer of 1861, collecting information on fortifications and Confederate plans. He was found out in Memphis and barely escaped with his life. Pinkerton's agency specialized in counter-espionage, identifying Confederate spies in the Washington area. Pinkerton played up to the demands of General George McClellan with exaggerated overestimates of the strength of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan mistakenly thought he was outnumbered, and played a very cautious role.[38][39] Spies and scouts typically reported directly to the commanders of armies in the field. They provided details on troop movements and strengths. The distinction between spies and scouts was one that had life or death consequences. If a suspect was seized while in disguise and not in his army's uniform, the sentence was often to be hanged.[40]

Intelligence gathering for the Confederates focused on Alexandria, Virginia, and the surrounding area. Thomas Jordan created a network of agents that included Rose O'Neal Greenhow. Greenhow delivered reports to Jordan via the "Secret Line," the system used to smuggle letters, intelligence reports, and other documents to Confederate officials. The Confederacy's Signal Corps was devoted primarily to communications and intercepts, but it also included a covert agency called the Confederate Secret Service Bureau, which ran espionage and counter-espionage operations in the North including two networks in Washington.[41][42]

In both armies, the cavalry service was the main instrument in military intelligence, using direct observation, Drafting map, and obtaining copies of local maps and local newspapers.[43] When General Robert E. Lee invaded Pennsylvania in the Gettysburg campaign of June 1863, his cavalry commander J. E. B. Stuart went on a long unauthorized raid, so Lee was operating blind, unaware that he was being trapped by Union forces. Lee later said that his Gettysburg campaign, "was commenced in the absence of correct intelligence. It was continued in the effort to overcome the difficulties by which we were surrounded."[44]

Military Intelligence

[edit]Austria

[edit]

Shaken by the revolutionary years 1848–1849, the Austrian Empire founded the Evidenzbureau in 1850 as the first permanent military intelligence service. It was first used in the 1859 Austro-Sardinian war and the 1866 campaign against Prussia, albeit with little success. The bureau collected intelligence of military relevance from various sources into daily reports to the Chief of Staff (Generalstabschef) and weekly reports to Emperor Franz Joseph. Sections of the Evidenzbureau were assigned different regions; the most important one was aimed against Russia.

Great Britain

[edit]During the Crimean War of 1854, the Topographical & Statistic Department T&SD was established within the British War Office as an embryonic military intelligence organization. The department initially focused on the accurate mapmaking of strategically sensitive locations and the collation of militarily relevant statistics. After the deficiencies in the British Army's performance during the war became known, a large-scale reform of army institutions was overseen by Edward Cardwell. As part of this, the T&SD was reorganized as the Intelligence Branch of the War Office in 1873 with the mission to "collect and classify all possible information relating to the strength, organization etc. of foreign armies... to keep themselves acquainted with the progress made by foreign countries in military art and science..."[45]

France

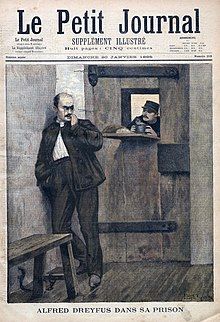

[edit]The French Ministry of War authorized the creation of the Deuxième Bureau on June 8, 1871, a service charged with performing "research on enemy plans and operations."[46] This was followed a year later by the creation of a military counter-espionage service. It was this latter service that was discredited through its actions over the notorious Dreyfus Affair, where a French Jewish officer was falsely accused of handing over military secrets to the Germans. As a result of the political division that ensued, responsibility for counter-espionage was moved to the civilian control of the Ministry of the Interior.

Germany

[edit]Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke the Younger established a military intelligence unit, Abteilung (Section) IIIb, to the German General Staff in 1889 which steadily expanded its operations into France and Russia.

Italy

[edit]The Italian Ufficio Informazioni del Comando Supremo was put on a permanent footing in 1900.

Russia

[edit]After Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, Russian military intelligence was reorganized under the 7th Section of the 2nd executive board of the great imperial headquarters.[47]

Naval Intelligence

[edit]It was not just the army that felt a need for military intelligence. Soon, naval establishments were demanding similar capabilities from their national governments to allow them to keep abreast of technological and strategic developments in rival countries.

The Naval Intelligence Division was set up as the independent intelligence arm of the British Admiralty in 1882 (initially as the Foreign Intelligence Committee) and was headed by Captain William Henry Hall.[48] The division was initially responsible for fleet mobilization and war plans as well as foreign intelligence collection; in the 1900s two further responsibilities – issues of strategy and defence and the protection of merchant shipping – were added.

In the United States the Naval intelligence originated in 1882 "for the purpose of collecting and recording such naval information as may be useful to the Department in time of war, as well as in peace." This was followed in October 1885 by the Military Information Division, the first standing military intelligence agency of the United States with the duty of collecting military data on foreign nations.[49]

In 1900, the Imperial German Navy established the Nachrichten-Abteilung, which was devoted to gathering intelligence on Britain. The navies of Italy, Russia and Austria-Hungary set up similar services as well.

Counterintelligence

[edit]

As espionage became more widely used, it became imperative to expand the role of existing police and internal security forces into a role of detecting and countering foreign spies. The Austro-Hungarian Evidenzbureau was entrusted with the role from the late 19th century to counter the actions of the Pan-Slavist movement operating out of Serbia.

Russia's Okhrana was formed in 1880 to combat political terrorism and left-wing revolutionary activity throughout the Russian Empire, but was also tasked with countering enemy espionage.[50] Its main concern was the activities of revolutionaries, who often worked and plotted subversive actions from abroad. It created an antenna in Paris run by Pyotr Rachkovsky to monitor their activities. The agency used many methods to achieve its goals, including covert operations, undercover agents, and "perlustration" — the interception and reading of private correspondence. The Okhrana became notorious for its use of agents provocateurs who often succeeded in penetrating the activities of revolutionary groups including the Bolsheviks.[51]

In the 1890s Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery captain in the French Army, was twice falsely convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans. The case convulsed France regarding antisemitism and xenophobia for a decade until he was fully exonerated. It raised public awareness of the rapidly developing world of espionage.[52] Responsibility for military counter-espionage was passed in 1899 to the Sûreté générale – an agency originally responsible for order enforcement and public safety – and overseen by the Ministry of the Interior.[53]

In Britain the Second Boer War (1899–1902) saw a difficult and highly controversial victory over hard-fighting Boer Commandos in South Africa. One response was to build up counterinsurgency policies. After that came the "Edwardian Spy-Fever," with rumors of German spies under every bed.[54]

20th century

[edit]Civil intelligence agencies

[edit]In Britain, the Secret Service Bureau was split into a foreign and counter-intelligence domestic service in 1910. The latter, headed by Sir Vernon Kell, originally aimed at calming public fears of large-scale German espionage.[55] As the Service was not authorized with police powers, Kell liaised extensively with the Special Branch of Scotland Yard (headed by Basil Thomson), and succeeded in disrupting the work of Indian revolutionaries collaborating with the Germans during the war.

Integrated intelligence agencies run directly by governments were also established. The British Secret Service Bureau (SIS from c. 1920) was founded in 1909 as the first independent and interdepartmental agency fully in control over all British government espionage activities.

At a time of widespread and growing anti-German feeling and fear, plans were drawn up for an extensive offensive intelligence system to be used as an instrument in the event of a European war. Due to intense lobbying by William Melville after he obtained German mobilization plans and proof of German financial support to the Boers, the government authorized the creation of a new intelligence section in the War Office, MO3 (subsequently re-designated "M05"), headed by Melville, in 1903. Working under cover from a flat in London, Melville ran both counterintelligence and foreign-intelligence operations, capitalizing on the knowledge and foreign contacts he had accumulated during his years running Special Branch.

Due to its success, the Government Committee on Intelligence, with support from Richard Haldane (the Secretary of State for War) and from Winston Churchill (the President of the Board of Trade), established the Secret Service Bureau in 1909. It consisted of nineteen military-intelligence departments – MI1 to MI19, but MI5 and MI6 came to be the most recognized as they are the only ones to have remained active to this day.

The Bureau was a joint initiative of the Admiralty, the War Office and the Foreign Office to control secret-intelligence operations in the UK and overseas, particularly concentrating on the activities of the Imperial German Government. Its first director was Captain Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming. In 1910, the bureau was split into naval and army sections which, over time, specialised in foreign espionage and internal counter-espionage activities respectively. The Secret Service initially focused its resources on gathering intelligence on German shipbuilding plans and operations. The SIS consciously refrained from conducting espionage activity in France so as not to jeopardize the burgeoning alliance between the two countries.

For the first time, the government had access to a peacetime, centralized independent intelligence bureaucracy with indexed registries and defined procedures, as opposed to the more ad hoc methods used previously. Instead of a system whereby rival departments and military services would work on their own priorities with little to no consultation or co-operation with each other, the newly established Secret Intelligence Service was interdepartmental, and submitted its intelligence reports to all relevant government departments.[56]

First World War

[edit]By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 all the major powers had highly sophisticated structures in place for the training and handling of spies and for the processing of the intelligence information obtained through espionage. The Dreyfus Affair of 1894-1906, which involved accusations of international espionage and treason, contributed much to public interest in espionage from 1894 onwards.[57][58]

The spy novel emerged as a distinct genre of fiction in the late-19th century; it dealt with themes such as colonial rivalry, the growing threat of conflict in Europe and the revolutionary and anarchist domestic threats. The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers defined the genre: the novel played on public fears of a German plan to invade Britain (an amateur spy uncovers the nefarious plot). In the wake of Childers's success there followed a flood of imitators, including William Le Queux and E. Phillips Oppenheim.

The First World War (1914–1918) saw the honing and refinement of modern espionage techniques as all the belligerent powers utilized their intelligence services to obtain military intelligence, to commit acts of sabotage and to carry out propaganda. As the battle fronts became static and armies dug down in trenches, cavalry reconnaissance became of very limited effectiveness.[59]

Information gathered at the battlefront from the interrogation of prisoners-of-war typically could give insight only into local enemy actions of limited duration. To obtain high-level information on an enemy's strategic intentions, its military capabilities and deployment, required undercover spy-rings operating deep in enemy territory. On the Western Front the advantage lay with the Western Allies, as for most of the war the Imperial German Army occupied Belgium and parts of northern France amidst a large and disaffected native population that agents could organize into collecting and transmitting vital intelligence.[59]

British and French intelligence services recruited Belgian or French refugees and infiltrated these agents behind enemy lines via the Netherlands – a neutral country. Many collaborators were then recruited from the local population, who were mainly driven by patriotism and hatred of the harsh German occupation. By the end of the war the Allies had set up over 250 networks, comprising more than 6,400 Belgian and French citizens. These rings concentrated on infiltrating the German railway network so that the Allied powers could receive advance warning of strategic movements of troops and ammunition.[59]

In 1916 Walthère Dewé founded the Dame Blanche ("White Lady") network as an underground intelligence group which became the most effective Allied spy-ring in German-occupied Belgium. It supplied as much as 75% of the intelligence collected from occupied Belgium and northern France to the Allies. By the end of the war, its 1,300 agents covered all of occupied Belgium, northern France and, through a collaboration with the Alice Network led by Louise de Bettignies, occupied Luxembourg. The network was able to provide a crucial few days warning before the launch of the German 1918 Spring Offensive.[60]

German intelligence was only ever able to recruit a very small number of spies. These were trained at an academy run by the Kriegsnachrichtenstelle (War Intelligence Office) in Antwerp and headed by Elsbeth Schragmüller, known as "Fräulein Doktor". These agents were generally isolated and unable to rely on a large support network for the relaying of information. The most famous German spy was Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, a Dutch exotic dancer with the stage name Mata Hari. As a Dutch subject, she was able to cross national borders freely. In 1916 she was arrested and brought to London where she was interrogated at length by Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner at New Scotland Yard. She eventually claimed to be working for French intelligence. In fact, she had entered German service from 1915, and sent her reports to the mission in the German embassy in Madrid.[61] In January 1917, the German military attaché in Madrid transmitted radio messages to Berlin describing the helpful activities of a German spy code-named H-21. French intelligence-agents intercepted the messages and, from the information contained, identified H-21 as Mata Hari. She was executed by firing squad on 15 October 1917.

German spies in Britain did not meet with much success – the German spy-ring operating in Britain was successfully disrupted by MI5 under Vernon Kell on the day after the declaration of the war. Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, announced that "within the last twenty-four hours no fewer than twenty-one spies, or suspected spies, have been arrested in various places all over the country, chiefly in important military or naval centres, some of them long known to the authorities to be spies",[62][63]

One exception was Jules C. Silber, who evaded MI5 investigations and obtained a position at the British censor's office in 1914. Using mailed window-envelopes that had already been stamped and cleared he was able to forward microfilm to Germany that contained increasingly important information. Silber was regularly promoted and ended up in the position of chief censor, which enabled him to analyze all suspect documents.[64]

The British economic blockade of Germany was made effective through the support of spy networks operating out of the neutral Netherlands. Agents on the ground determined points of weakness in the naval blockade and relayed this information to the Royal Navy. The blockade led to severe food deprivation in Germany contributed greatly to the collapse of the Central Powers' war effort in 1918.[65]

Codebreaking

[edit]

Two new methods for intelligence collection developed over the course of the war – aerial reconnaissance and photography; and the interception and decryption of radio signals.[65] The British rapidly built up great expertise in the newly emerging field of signals intelligence and codebreaking.

In 1911, a subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence on cable communications concluded that in the event of war with Germany, German-owned submarine cables should be destroyed. On the night of 3 August 1914, the cable ship Alert located and cut Germany's five trans-Atlantic cables, which ran under the English Channel. Soon after, the six cables running between Britain and Germany were cut.[66] As an immediate consequence, there was a significant increase in messages sent via cables belonging to other countries, and by radio. These could now be intercepted, but codes and ciphers were naturally used to hide the meaning of the messages, and neither Britain nor Germany had any established organisations to decode and interpret such messages. At the start of the war, the navy had only one wireless station for intercepting messages, at Stockton-on-Tees. However, installations belonging to the Post Office and the Marconi Company, as well as private individuals who had access to radio equipment, began recording messages from Germany.[67]

Room 40, formed in October 1914 under Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, was the section in the British Admiralty most identified with the British crypto analysis effort during the war. The basis of Room 40 operations evolved around an Imperial German Navy codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), and around maps (containing coded squares), which were obtained from three different sources in the early months of the war. Alfred Ewing directed Room 40 until May 1917, when direct control passed to Captain (later Admiral) Reginald "Blinker" Hall, assisted by William Milbourne James.[68]

A similar organization began in the Military Intelligence department of the War Office, which become known as MI1b, and Colonel Macdonagh proposed that the two organizations should work together, decoding messages concerning the Western Front in France. A sophisticated interception system (known as 'Y' service), together with the post office and Marconi receiving stations, grew rapidly to the point it could intercept almost all official German messages.[67]

As the number of intercepted messages increased it became necessary to decide which were unimportant and should just be logged, and which should be passed on to Room 40. The German fleet was in the habit each day of wirelessing the exact position of each ship and giving regular position-reports when at sea. It was possible to build up a precise picture of the normal operation of the High Seas Fleet, indeed to infer from the routes they chose where defensive minefields had been placed and where it was safe for ships to operate. Whenever the British detected a change to the normal pattern, it immediately signalled that some operation was about to take place and a warning could be given. Detailed information about submarine movements was also available.[69]

Both the British and German interception services began to experiment with direction-finding radio equipment at the start of 1915. Captain H. J. Round, working for Marconi, had been carrying out experiments for the army in France, and Hall instructed him to build a direction-finding system for the navy. Stations were built along the coast, and by May 1915 the Admiralty was able to track German submarines crossing the North Sea. Some of these stations also acted as 'Y' stations to collect German messages, but a new section was created within Room 40 to plot the positions of ships from the directional reports. The German fleet made no attempts to restrict its use of wireless until 1917, and then only in response to perceived British use of direction finding, not because it believed messages were being decoded.[70]

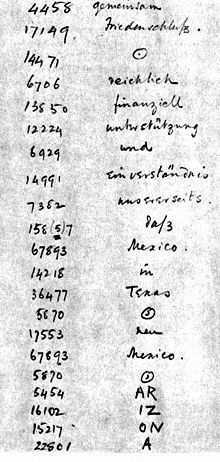

Room 40 played an important role in several naval engagements during the war, notably in detecting major German sorties into the North Sea that led to the battles of Dogger Bank (1915) and Jutland (1916) when the British fleet was sent out to intercept them. However its most important contribution was probably in decrypting the Zimmermann Telegram, a telegram from the German Foreign Office sent via Washington to its ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico in January 1917.

In the telegram's plain text, Nigel de Grey and William Montgomery learned of the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann's offer to Mexico to join the war as a German ally. The telegram was made public by the United States, which declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. This event demonstrated how the course of a war could be changed by effective intelligence operations.[71]

The British were reading the Americans' secret messages by late 1915.[72]

Russian Revolution

[edit]The outbreak of revolution in Russia in March 1917 and the subsequent seizure of power in November 1917 by the Bolsheviks, a party deeply hostile towards the capitalist powers, was an important catalyst for the development of modern international espionage techniques. A key figure was Sidney Reilly, a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by Scotland Yard and the Secret Intelligence Service. He set the standard for modern espionage, turning it from a gentleman's amateurish game to a ruthless and professional methodology for the achievement of military and political ends. Reilly's career culminated in a failed attempt to depose the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and assassinate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in 1918.[73]

Another pivotal figure was Sir Paul Dukes (1889-1967), arguably the first professional spy of the modern age.[74] Recruited personally by Mansfield Smith-Cumming to act as a secret agent in Imperial Russia, he set up elaborate plans to help prominent White Russians escape from Soviet prisons after the October Revolution and smuggled hundreds of them into Finland. Known as the "Man of a Hundred Faces", Dukes continued his use of disguises, which aided him in assuming a number of identities and gained him access to numerous Bolshevik organizations. He successfully infiltrated the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Comintern, and the political police, or CHEKA. Dukes also learned of the inner workings of the Politburo, and passed the information to British intelligence.

In the course of a few months in 1918-1919, Dukes, Hall, and Reilly succeeded in infiltrating Lenin's inner circle, and gaining access to the activities of the Cheka and the Communist International at the highest level. This helped to convince the British government of the importance of a well-funded secret-intelligence service in peacetime as a key component in formulating foreign policy. Churchill, once again a member of the UK cabinet in this period, argued that intercepted communications were more useful "as a means of forming a true judgment of public policy than any other source of knowledge at the disposal of the State."[75]

Interwar

[edit]Nazi Germany

[edit]The intelligence gathering efforts of Nazi Germany (1933-1945) were largely ineffective. Berlin operated two espionage networks against the United States. Both suffered from careless recruiting, inadequate planning, and faulty execution. The FBI captured bungling spies, while poorly-designed sabotage efforts all failed. Adolf Hitler's anti-Semitic prejudices about Jewish control of the U.S. interfered with objective evaluation of American capabilities. Hitler's propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels deceived top officials who repeated his propagandistic exaggerations.[76][77]

Soviet Union

[edit]The Soviet GRU (military intelligence), originating in 1918, started operating throughout the world. Communist sympathisers and fellow-travellers in groups aligned with the Comintern (founded in 1919 and operating until 1943) were also widespread.[78]

Second World War

[edit]Britain MI6 and Special Operations Executive

[edit]Churchill's order to "set Europe ablaze," was undertaken by the British Secret Service or Secret Intelligence Service, who developed a plan to train spies and saboteurs. Eventually, this would become the SOE or Special Operations Executive, and to ultimately involve the United States in their training facilities. Sir William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, suggested to President Roosevelt that William J. Donovan devise a plan for an intelligence network modeled after the British Secret Intelligence Service or MI6 and Special Operations Executive's (SOE) framework. Accordingly, the first American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents in Canada were sent for training in a facility set up by Stephenson, with guidance from English intelligence instructors, who provided the OSS trainees with the knowledge needed to come back and train other OSS agents. Setting German-occupied Europe ablaze with sabotage and partisan resistance groups was the mission. Through covert special operations teams, operating under the new Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the OSS' Special Operations teams, these men would be infiltrated into occupied countries to help organize local resistance groups and supply them with logistical support: weapons, clothing, food, money, and direct them in attacks against the Axis powers. Through subversion, sabotage, and the direction of local guerrilla forces, SOE British agents and OSS teams had the mission of infiltrating behind enemy lines and wreaked havoc on the German infrastructure, so much, that an untold number of men were required to keep this in check, and kept the Germans off balance continuously like the French maquis. They actively resisted the German occupation of France, as did the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) partisans who were armed and fed by both the OSS and SOE during the German occupation of Greece.

MAGIC: U.S. breaks Japanese code

[edit]Magic was an American cryptanalysis project focused on Japanese codes in the 1930s and 1940s. It involved the U.S. Army's Signals Intelligence Service (SIS) and the U.S. Navy's Communication Special Unit.[79] Magic combined cryptologic capabilities into the Research Bureau with Army, Navy and civilian experts all under one roof. Their most important successes involved RED, BLUE, and PURPLE.[80]

In 1923, a United States Navy officer acquired a stolen copy of the Secret Operating Code codebook used by the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War I. Photographs of the codebook were given to the cryptanalysts at the Research Desk and the processed code was kept in red-colored folders (to indicate its Top Secret classification). This code was called "RED". In 1930, Japan created a more complex code that was codenamed BLUE, although RED was still being used for low-level communications. It was quickly broken by the Research Desk no later than 1932. US Military Intelligence COMINT listening stations began monitoring command-to-fleet, ship-to-ship, and land-based communications for BLUE messages. After Germany declared war in 1939, it sent technical assistance to upgrade Japanese communications and cryptography capabilities. One part was to send them modified Enigma machines to secure Japan's high-level communications with Germany. The new code, codenamed PURPLE (from the color obtained by mixing red and blue), baffled the codebreakers until they realized that it was not a manual additive or substitution code like RED and BLUE, but a machine-generated code similar to Germany's Enigma cipher. Decoding was slow and much of the traffic was still hard to break. By the time the traffic was decoded and translated, the contents were often out of date. A reverse-engineered machine could figure out some of the PURPLE code by replicating some of the settings of the Japanese Enigma machines. This sped up decoding and the addition of more translators on staff in 1942 made it easier and quicker to decipher the traffic intercepted. The Japanese Foreign Office used a cipher machine to encrypt its diplomatic messages. The machine was called "PURPLE" by U.S. cryptographers. A message was typed into the machine, which enciphered and sent it to an identical machine. The receiving machine could decipher the message only if set to the correct settings, or keys. American cryptographers built a machine that could decrypt these messages. The PURPLE machine itself was first used by Japan in 1940. U.S. and British cryptographers had broken some PURPLE traffic well before the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, but the Japanese diplomats did not know or transmit any details.. The Japanese Navy used a completely different system, known as JN-25.[81]

U.S. cryptographers had decrypted and translated the 14-part Japanese PURPLE message breaking off ongoing negotiations with the U.S. at 1 p.m. Washington time on 7 December 1941, even before the Japanese Embassy in Washington could do so. As a result of the deciphering and typing difficulties at the embassy, the note was formally delivered after the attack began.

Throughout the war, the Allies routinely read both German and Japanese cryptography. The Japanese Ambassador to Germany, General Hiroshi Ōshima, routinely sent priceless information about German plans to Tokyo. This information was routinely intercepted and read by Roosevelt, Churchill and Eisenhower. Japanese diplomats assumed their PURPLE system was unbreakable and did not revise or replace it.[82]

United States OSS

[edit]President Franklin D. Roosevelt was obsessed with intelligence and deeply worried about German sabotage. However, there was no overarching American intelligence agency, and Roosevelt let the Army, the Navy, the State Department, and various other sources compete against each other, so that all the information poured into the White House, but was not systematically shared with other agencies. The British Secret Service fascinated Roosevelt early on, and to him, an intelligence service modeled on the British was necessary to prevent false reports (e.g. the Germans having designs to take over Latin America). Roosevelt followed MAGIC intercept to Japan religiously, but set it up so that the Army and Navy briefed him on alternating days. Finally he turned to William (Wild Bill) Donovan to run a new agency the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) which in 1942 became the Office of Strategic Services or OSS. It became Roosevelt's most trusted source of secrets, and after the war OSS eventually became the CIA.[83][84] The COI had a staff of 2,300 in June 1942; OSS reached 5,000 personnel by September 1943. In all 35,000 men and women served in the OSS by the time it closed in 1947.[85]

The Army and Navy were proud of their long-established intelligence services and avoided the OSS as much as possible, banning it from the Pacific theaters. The Army tried and failed to prevent OSS operations in China.[86]

An agreement with Britain in 1942 divided responsibilities, with SOE taking the lead for most of Europe, including the Balkans and OSS took primary responsibility for China and North Africa. OSS experts and spies were trained at facilities in the United States and around the world.[87] The military arm of the OSS, was the Operational Group Command (OGC), which operated sabotage missions in the European and Mediterranean theaters, with a special focus on Italy and the Balkans. OSS was a rival force with SOE in the Italian Civil War in aiding and directing Italian resistance movement groups.[88]

The "Research and Analysis" branch of OSS brought together numerous academics and experts who proved especially useful in providing a highly detailed overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the German war effort.[89] In direct operations it was successful in supporting Operation Torch in French North Africa in 1942, where it identified pro-Allied potential supporters and located landing sites. OSS operations in neutral countries, especially Stockholm, Sweden, provided in-depth information on German advanced technology. The Madrid station set up agent networks in France that supported the Allied invasion of southern France in 1944.

Most famous were the operations in Switzerland run by Allen Dulles that provided extensive information on German strength, air defenses, submarine production, the V-1, V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and aircraft (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.). It revealed some of the secret German efforts in chemical and biological warfare. They also received information about mass executions and concentration camps. The resistance group around the later executed priest Heinrich Maier, which provided much of this information, was then uncovered by a double spy who worked for the OSS, the German Abwehr and even the Sicherheitsdienst of the SS. Despite the Gestapo's use of torture, the Germans were unable to uncover the true extent of the group's success, particularly in providing information for Operation Crossbow and Operation Hydra, both preliminary missions for Operation Overlord.[90][91] Switzerland's station also supported resistance fighters in France and Italy, and helped with the surrender of German forces in Italy in 1945.[92][93]

Counterespionage

[edit]Informants were common in World War II. In November 1939, the German Hans Ferdinand Mayer sent what is called the Oslo Report to inform the British of German technology and projects in an effort to undermine the Nazi regime. The Réseau AGIR was a French network developed after the fall of France that reported the start of construction of V-weapon installations in Occupied France to the British.

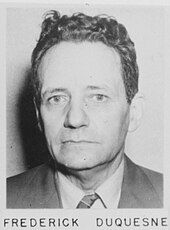

The MI5 in Britain and the FBI in the U.S. identified all the German spies, and "turned" all but one into double agents so that their reports to Berlin were actually rewritten by counterespionage teams. The FBI had the chief role in American counterespionage and rounded up all the German spies in June 1941.[95] Counterespionage included the use of turned Double Cross agents to misinform Nazi Germany of impact points during the Blitz and internment of Japanese in the US against "Japan's wartime spy program". Additional WWII espionage examples include Soviet spying on the US Manhattan project, the German Duquesne Spy Ring convicted in the US, and the Soviet Red Orchestra spying on Nazi Germany.

Cold War Period

[edit]After 1990s new memoirs and archival materials have opened up the study of espionage and intelligence during the Cold War. Scholars are reviewing how its origins, its course, and its outcome were shaped by the intelligence activities of the United States, the Soviet Union, and other key countries.[96][97] Special attention is paid to how complex images of one's adversaries were shaped by secret intelligence that is now publicly known.[98]

All major powers engaged in espionage, using a great variety of spies, double agents, and new technologies such as the tapping of telephone cables.[4] The most famous and active organizations were the American CIA,[99] the Soviet KGB,[100] and the British MI6.[101] The East German Stasi, unlike the others, was primarily concerned with internal security, but its Main Directorate for Reconnaissance operated espionage activities around the world.[102] The CIA secretly subsidized and promoted anti-communist cultural activities and organizations.[103] The CIA was also involved in European politics, especially in Italy.[104] Espionage took place all over the world, but Berlin was the most important battleground for spying activity.[105]

Enough top secret archival information has been released so that historian Raymond L. Garthoff concludes there probably was parity in the quantity and quality of secret information obtained by each side. However, the Soviets probably had an advantage in terms of HUMINT (espionage) and "sometimes in its reach into high policy circles." In terms of decisive impact, however, he concludes:[106]

- We also can now have high confidence in the judgment that there were no successful “moles” at the political decision-making level on either side. Similarly, there is no evidence, on either side, of any major political or military decision that was prematurely discovered through espionage and thwarted by the other side. There also is no evidence of any major political or military decision that was crucially influenced (much less generated) by an agent of the other side.

The USSR and East Germany proved especially successful in placing spies in Britain and West Germany. Moscow was largely unable to repeat its successes from 1933 to 1945 in the United States. NATO, on the other hand, also had a few successes of importance, of whom Oleg Gordievsky was perhaps the most influential. He was a senior KGB officer who was a double agent on behalf of Britain's MI6, providing a stream of high-grade intelligence that had an important influence on the thinking of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. He was spotted by Aldrich Ames a Soviet agent who worked for the CIA, but he was successfully exfiltrated from Moscow in 1985. Biographer Ben McIntyre argues he was the West's most valuable human asset, especially for his deep psychological insights into the inner circles of the Kremlin. He convinced Washington and London that the fierceness and bellicosity of the Kremlin was a product of fear, and military weakness, rather than an urge for world conquest. Thatcher and Reagan concluded they could moderate their own anti-Soviet rhetoric, as successfully happened when Mikhail Gorbachev took power, thus ending the Cold War.[107]

In addition to usual espionage, the Western agencies paid special attention to debriefing Eastern Bloc defectors.[108]

Middle East

[edit]The United Kingdom's MI6 was involved in the region to protect its interests, notably collaborating with the CIA in Iran, to bring back Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to power in a coup in 1953, after the Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh attempted to nationalise the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.[109] The CIA operated with the intent to curtail the influence of the USSR known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, by funding anti-communist organisations such as the Grey Wolves in Turkey.[110] Middle Eastern states developed sophisticated intelligence and security agencies referred to as Mukhabarat (Arabic: المخابرات El Mukhabarat), primarily used domestically for population control and surveillance,[111] notably in Iran, Egypt, Iraq and Syria under Ba'athist rule and Libya. According to Owen L. Sirrs, the 1967 War between Israel and the Arab coalition of Egypt, Syria and Jordan, signalled a failure by Egyptian intelligence to adequately evaluate the military capabilities of their foes.[112] The Yom Kippur War can be attributed to intelligence failure on the side of Israel, caused by a over confidence that Egypt and Syria were not reading for an invasion, despite intelligence proving the contrary provided by high ranking Egyptian Official Ashraf Marwan.[113]

| Country | Middle Eastern Intelligence & Security Agencies during the Cold War Era | Years Active | Missions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | General Intelligence Service[114] | 1954–Present[114] | Counterintelligence, gathering of foreign "political and economic intelligence"[114] |

| Military Intelligence Departement[115] | 1952–Present[115] | Military reconnaissance, contain anti-regime dissent within the Army[114] | |

| State Security Investigation Service[115] | 1952- 2011[115] | Secret policing, surveillance of civilians[115] | |

| Syria | General Intelligence Directorate (GID)[116] | 1971–Present[117] | Surveillance of civilians, secret policing[118] |

| Political Security Directorate[116] (Department of the GID) | Monitoring of parties and media, foreign intelligence gathering[118] | ||

| Military Intelligence Directorate[116] | 1969–Present[117] | Military Policing, unconventional Warfare[118] | |

| Air Force Intelligence Directorate[116] | 1963–Present[117] | Security of political bodies, overseas interventions[118] | |

| Iraq | Special Security Organisation | 1982 - 2003[119] | Physical security of the president, monitoring of ministries, armed forces, security and intelligence services[120] |

| Directorate of General Security | 1921 - 2003[121] | Surveillance of civilians, monitoring of political & economic criminal activities[121] | |

| Intelligence Services | 1964 - 2003[122] | Internal and external intelligence gathering, monitoring of political parties, support of opposition groups in rival countries, sabotage and assassination of high targets[123] | |

| Jordan | General Intelligence Directorate[124] | 1964–Present[125] | Secret policing, foreign intelligence gathering, counterterrorism[124] |

| Iran (Shah Period) | Organisation of Intelligence and National Security (SAVAK) | 1957[126] - 1979 | Foreign and domestic intelligence gathering, monitoring of opposition[126] |

| Turkey | National Security Service (MAH) | 1926 - 1965[127] | Foreign intelligence gathering and counterintelligence[127] |

| National Intelligence Organisation (MIT) | 1965–Present[127] | ||

| Libya | The Jamahiriya Security Organisation | 1992 - 2011[128] | Foreign & internal intelligence gathering, monitoring of the Libyan diaspora, sabotage, funding of dissident groups abroad, terrorism |

| Military Secret Service[129] | unknown | [clarification needed] | |

| Intelligence Bureau of the Leader[128] | 1970s - 2011[128] | Supervision of the activities of the Military Secret Service, Jamahiriya Security Organisation, and revolutionary committees, physical security of Gaddafi and his Revolutionary nuns[128] | |

| Saudi Arabia | General Intelligence Presidency | [clarification needed] | External intelligence gathering, foreign security operations, counterterrorism, foreign liaison[130] |

| General Security Service[131] | [clarification needed] | Internal Security | |

| General Directorate of Counterintelligence[131] | [clarification needed] | Counterintelligence | |

| Lebanon | General Directorate of General Security | 1921[132] | External & internal intelligence gathering, monitoring of media, foreign liaison and regulating entry of foreigners[133] |

| Israel | Mossad | 1949[citation needed] | Intelligence gathering abroad, foreign liaison, psychological warfare, unconventional warfare, sabotage and assassinations[citation needed] |

| Shin Bet (Shabak) | 1948[citation needed] | Counterespionage, monitoring of dissidents and counterterrorism[citation needed] | |

| Israeli Military Intelligence (Aman) | 1953[134] | Gathering & analysing military intelligence from communication & electronic sources[citation needed] |

Post-Cold War

[edit]In the United States, there are seventeen[135] (taking military intelligence into consideration, it is 22 agencies) federal agencies that form the United States Intelligence Community. The Central Intelligence Agency operates the National Clandestine Service (NCS)[136] to collect human intelligence and perform Covert operations.[137] The National Security Agency collects Signals Intelligence. Originally the CIA spearheaded the US-IC. Following the September 11 attacks the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) was created to promulgate information-sharing.

Since the 19th century new approaches have included professional police organizations, the police state and geopolitics. New intelligence methods have emerged, most recently imagery intelligence, signals intelligence, cryptanalysis and spy satellites.

Counter-terrorism

[edit]

Western intelligence agencies have progressively turned from traditional state spying to missions resembling international policing: the tracking, spying, arrest and interrogation of high-profile targets in prevention of terrorist threats.[138] During The Troubles, the British Security Service (MI5) created a counterterrorism cell in response to the activities of the Irish Republican Army, active in Northern Ireland and mainland Britain, including the interception of arms shipment from Libya.[139] In France, the General Directorate for Internal Security (DGSI) engaged in counter-terrorism already in the 1980s in the context of active Basque and Corsican nationalist movements, as well as Middle Eastern Organisations such as the Palestinian Abu Nidal Organization and the Lebanese Hezbollah.[140] In the 1990s, Western Intelligence services started to pay increasing attention to Islamic Terrorism, notably due to the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993 and the attacks on the French Public Transport in 1995 by the Algerian Armed Islamic Group (GIA).[141] Islamic Terrorism became the primary focus of the US Intelligence services after the 9/11 Attacks by Al-Qaeda, leading to the Invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, and ultimately to the tracking and killing of Osama Ben Laden in 2011.

Traditional human intelligence is obsolete when it concerns Islamic terrorist organisations for several reasons: infiltrating such organisations is more difficult than dealing with states, recruiting from within is significantly riskier for loyalty reasons, and working with informants that are engaged in attacks poses ethical concerns.[142] Counter-terrorism information gathering strategies rely on collaboration with foreign intelligence services and prisoner interrogation.[138]

War in Afghanistan 2001 - 2021

[edit]In December 2009, Jordanian doctor Humam al-Balawi performed a suicide bomb attack at the Camp Chapman American military base near Khost which led to the death of 7 CIA operatives, including the chief of the base, one Jordanian intelligence officer and an afghan driver.[139]

Iraq War 2003 - 2011

[edit]

The most dramatic failure of intelligence in this era was the false discovery of weapons of mass destruction in Ba'athist Iraq in 2003. American and British intelligence agencies agreed on balance that the WMD were being built and would threaten the peace. They launched a full-scale invasion that overthrew the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein. The result was decades of turmoil and large-scale violence. There were in fact no weapons of mass destruction, but the Iraqi government had pretended they existed so that it could deter the sort of attack that in fact resulted.[143][144]

Israel

[edit]In Israel, the Shin Bet unit is the agency for homeland security and counter intelligence. The department for secret and confidential counter terrorist operations is called Kidon.[145] It is part of the national intelligence agency Mossad and can also operate in other capacities.[145] Kidon was described as "an elite group of expert assassins who operate under the Caesarea branch of the espionage organization." The unit only recruits from "former soldiers from the elite IDF special force units."[146] There is almost no reliable information available on this ultra-secret organization.

Cyber Espionage

[edit]The Panama Papers

[edit]On May 6, 2016, documents entitled the "Panama Papers" provided by a John Doe were leaked online revealing the operations of over 214,000 shell companies from all over the world.[147] The leak was announced on April 3, 2016, before being published on the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ (ICIJ) website.[147] The Panama Papers targeted law firm and offshore service provider Mossack Fonseca & Co., as well as their clients.[147] In total, 11.5 million confidential documents were published online.[147]

The leaked documents exposed how companies used offshore vehicles to evade taxation and to fund bribes that would be used to coerce corruptible countries into contracts.[147] The documents also exposed all parties involved, from shareholders to directors, and their relationships to each other.[147] Individuals using company funds for personal use was also revealed, such as Russian president Vladimir Putin using funds to pay for his daughter’s wedding.[148] The documents revealed that Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif was found to be untruthful regarding how he financed his family homes, which led to his disqualification and removal from power.[149] Other notable people involved include former vice-president of Iraq Ayad Allawi, and former president of Egypt Alaa Mubarak.[148]

Since the release of the Panama Papers, expropriation has become harder to disguise and resulted in many companies reducing their tax avoidance.[147] Company values have reduced an average of 0.9%.[147] The documents have sparked new debates on the ethics of offshore vehicles and tax havens.[148]

In March 2018, Mossack Fonesca & Co. officially ceased operation.[150]

The Palestine Papers

[edit]On the 23rd of January 2011 more than 1600 pages of confidential documents from the peace negotiations between the Israeli government and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were leaked to news channel al-Jazeera.[151] These documents contained "memos, emails, maps, minutes of private meetings, accounts of high-level exchanges, strategy papers, and Power Point presentations" that occurred as early as 1991.[151][152] Topics include the Israeli settlement in East Jerusalem, refugees and their right to return, the Goldstone Report, security cooperation, the Gaza Strip, and Hamas.[152] These documents were shocking to the public as they exposed the failure of the negotiations between Israel and Palestine.[152] Palestinians were angered due to the amendable nature of the Palestinian negotiators, as well as the condescending attitude the Israelis and Americans had towards said Palestinian negotiators.[151] Another revelation from the leak was the rebuttal of the belief that Palestinians were uncooperative during negotiations with the papers revealing Israel and the Americans were being disruptive.[152]

The papers revealed the Palestinian negotiators working against Palestinian popular opinion, such as exchanging land in the Arab Quarter for land elsewhere or willingness to define Israel as a Jewish state in exchange for refugees.[152] Many interpreted these decisions as evidence of weakness in the negotiators; though some sympathised with the negotiators, believing they did what was required for peace.[152] Palestinian negotiator, Saed Erekat called the documents lies, but also went on to say that the papers were non-binding and that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”.[152]

People from both parties condemned the release of these documents, some denouncing their authenticity and questioning the motives of whoever released them.[152] Some believe the documents to be fabricated, anti-Israeli propaganda as the leak coincides with al-Jazeera's airing of programs on the Jerusalem settlements.[151] Allegedly, the documents were leaked by multiple members of staff who worked within the negotiations, though some believe French-Palestinian lawyer Ziyad Clot was the source of the leak.[151][152]

Following the leak, protests occurred in Israel and Palestine, as well as in other countries over the world.[152] People began to question whether peace is a possible outcome in Israel and Palestine, and if the United States are capable of being a neutral party during peace talks.[152]

List of famous spies

[edit]

- Reign of Elizabeth I of England

- English Commonwealth

- John Thurloe, Cromwell's spy chief

- American Revolution

- Thomas Knowlton, first American Spy

- Nathan Hale

- Hercules Mulligan

- John Andre

- James Armistead

- Benjamin Tallmadge, case agent who organized of the Culper spy ring in New York City

- Napoleonic Wars

- American Civil War

- One of the innovations in the American Civil War was the use of proprietary companies for intelligence collection by the Union; see Allan Pinkerton.

- Confederate Secret Service

- Belle Boyd[153]

- Harriet Tubman

- Aceh War

- Second Boer War

- Russo-Japanese War

- Sidney Reilly

- Ho Liang-Shung

- Akashi Motojiro

- Arab-Israeli Conflict

World War I

[edit]- Fritz Joubert Duquesne

- Jules C. Silber

- Mata Hari

- Howard Burnham

- T.E. Lawrence

- Sidney Reilly

- Maria de Victorica

- Elsbeth Schragmüller

- 11 German spies were executed in the Tower of London.[154]

Other spies in popular culture

[edit]Gender roles

[edit]Spying has sometimes been considered a gentlemanly pursuit, with recruiting focused on military officers, or at least on persons of the class from whom officers are recruited. However, the demand for male soldiers, an increase in women's rights, and the tactical advantages of female spies led the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) to set aside any lingering Victorian Era prejudices and begin employing women in April 1942.[155] Their task was to transmit information from Nazi occupied France back to Allied Forces. The main strategic reason was that men in France faced a high risk of being interrogated by Nazi troops but women were less likely to arouse suspicion. In this way they made good couriers and proved equal to, if not more effective than, their male counterparts. Their participation in Organization and Radio Operation was also vital to the success of many operations, including the main network between Paris and London.

See also

[edit]- Intelligence agency

- Human intelligence (intelligence gathering), or HUMINT

- Imagery intelligence, or IMINT

- Signals intelligence, or SIGINT

- Germany

- Kenpeitai, the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services to 1945

- KGB, in Soviet Union

- Nuclear espionage

- Atomic spies in 1940s

- Recruitment of spies

- Soviet espionage in the United States

- Spy fiction

- United Kingdom

- United States government security breaches

- Espionage Act of 1917 in United States

- World War II espionage

- Office of Strategic Services, United States, World War II

- Special Operations Executive, of Great Britain in Second World War

References

[edit]- ^ Christopher Andrew and David Dilks, eds. The missing dimension: Governments and intelligence communities in the twentieth century (1984)

- ^ Christopher R. Moran, "The pursuit of intelligence history: Methods, sources, and trajectories in the United Kingdom." Studies in Intelligence 55.2 (2011): 33–55. online

- ^ John Prados, "Of Spies and Stratagems." in Thomas W. Zeiler, ed., A Companion to World War II (2012) 1: 482–500.

- ^ a b Raymond L. Garthoff, "Foreign intelligence and the historiography of the Cold War." Journal of Cold War Studies 6.2 (2004): 21–56.

- ^ Derek M. C. Yuen (2014). Deciphering Sun Tzu: How to Read 'The Art of War'. pp. 110–111. ISBN 9780199373512.

- ^ Philip H. J. Davies and Kristian C. Gustafson. eds. Intelligence Elsewhere: Spies and Espionage Outside the Anglosphere (2013) p. 45

- ^ Dany Shoham and Michael Liebig. "The intelligence dimension of Kautilyan statecraft and its implications for the present." Journal of Intelligence History 15.2 (2016): 119–138.

- ^ "Rahab ("the Harlot") and the Spies - For an informed reading of Joshua 2:1–24". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2019-06-24.

- ^ "Espionage in Ancient Rome". HistoryNet.

- ^ Aladashvili, Besik (2017). Fearless: A Fascinating Story of Secret Medieval Spies.

- ^ Soustelle, Jacques (2002). The Daily Life of the Aztecas. Phoenix Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-84212-508-3.

- ^ Andrew, Secret World (2018) pp 158–90.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Robert (2007) Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the Secret War that Saved England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84613-0. pp. 84–121.

- ^ Anna Maria Orofino, "'Coelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt': David Stradling (1537–c. 1595) and His Circle of Welsh Catholic Exiles in Continental Europe." British Catholic History 32.2 (2014): 139–158.

- ^ Stephen Budiansky, Her Majesty's spymaster : Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, and the birth of modern espionage (2005) online free to borrow

- ^ Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (2018), pp 242–91.

- ^ Jeremy Black, British Diplomats and Diplomacy, 1688–1800 (2001) pp 143–45. online

- ^ William J. Roosen, "The functioning of ambassadors under Louis XIV." French Historical Studies 6.3 (1970): 311–332. online

- ^ William James Roosen (1976). The Age of Louis XIV: The Rise of Modern Diplomacy. pp. 147–56. ISBN 9781412816670.

- ^ Alan Williams, "Domestic Espionage and the Myth of Police Omniscience in Eighteenth-Century Paris" Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings (1979), Vol. 8, pp 253–260.

- ^ Jeremy Black, "British intelligence and the mid‐eighteenth‐century crisis." Intelligence and National Security 2#2 (1987): 209–229.

- ^ T. L. Labutina, "Britanskii Diplomat I Razvedchik Charl'z Uitvort Pri Dvore Petra I." ["British diplomat and spy Charles Whitworth at the court of Peter I"] Voprosy Istorii (2010), Issue 11, p 124-135, in Russian.

- ^ John R. Harris, "The Rolt Memorial Lecture, 1984 Industrial Espionage in the Eighteenth Century." Industrial Archaeology Review 7.2 (1985): 127–138.

- ^ J.R. Harris, "French Industrial Espionage in Britain in the Eighteenth Century," Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Proceedings (1989) Part 1, Vol. 19, pp 242–256.

- ^ Juan Helguera Quijada, "The Beginnings of Industrial Espionage in Spain (1748–60)" History of Technology (2010), Vol. 30, p1-12

- ^ Alexander Rose, Washington's Spies: The Story of America's First Spy Ring (2006) pp 75, 224, 258–61. online free to borrow

- ^ Carl Van Doren, Secret History of the American Revolution: An Account of the Conspiracies of Benedict Arnold and Numerous Others Drawn from the Secret Service Papers of the British Headquarters in North America now for the first time examined and made public (1941) online free

- ^ Paul R. Misencik (2013). The Original American Spies: Seven Covert Agents of the Revolutionary War. p. 157. ISBN 9781476612911.

- ^ John A. Nagy, George Washington's Secret Spy War: The Making of Americas First Spymaster (2016) calls him "the eighteenth century's greatest spymaster" (p. 274).

- ^ Elizabeth Sparrow, "Secret Service under Pitt's Administrations, 1792–1806." History 83.270 (1998): 280–294. online

- ^ Alfred Cobban, "British Secret Service in France, 1784–1792", English Historical Review, 69 (1954), 226–61. online

- ^ Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793–1815 (2013) pp 122–52, 251–312.

- ^ Michael Durey, "William Wickham, the Christ Church Connection and the Rise and Fall of the Security Service in Britain, 1793–1801." English Historical Review 121.492 (2006): 714–745. online

- ^ Knight, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793–1815 (2013) pp 125–42.

- ^ Elizabth Sparrow Secret Service: British Agents in France 1792-1815 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1999) p. 243-248

- ^ Edward A. Whitcomb, "The Duties and Functions of Napoleon's External Agents." History 57#190 (1972): 189–204.

- ^ Philip H.J. Davies (2012). Intelligence and Government in Britain and the United States: A Comparative Perspective. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440802812.

- ^ Edwin C. Fishel, "Pinkerton and McClellan: Who Deceived Whom?." Civil War History 34.2 (1988): 115–142. Excerpt

- ^ James Mackay, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye (1996) downplays the exaggeration.

- ^ E.C. Fishel, The Secret War for The Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (1996).

- ^ Harnett, Kane T. (1954). Spies for the Blue and the Gray. Hanover House. pp. 27–29.

- ^ Markle, Donald E. (1994). Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War. Hippocrene Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0781802277.

- ^ John Keegan, Intelligence in War: The value—and limitations—of what the military can learn about the enemy (2004) pp 78–98

- ^ Warren C. Robinson (2007). Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 38, 124–29, quoting p 129. ISBN 978-0803205659.

- ^ Thomas G. Fergusson (1984). British Military Intelligence, 1870–1914: The Development of a Modern Intelligence Organization. University Publications of America. p. 45. ISBN 9780890935415.

- ^ Anciens des Services Spéciaux de la Défense Nationale ( France )

- ^ "Espionage".

- ^ Dorril, Stephen (2002). MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service. Simon & Schuster. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7432-1778-1.

- ^ "A Short History of Army Intelligence" (PDF). Michael E. Bigelow (Command Historian, United States Army Intelligence and Security Command. 2012. p. 10.

- ^ Frederic S. Zuckerman, The Tsarist Secret Police in Russian Society, 1880–1917 (1996) excerpt

- ^ Jonathan W. Daly, The Watchful State: Security Police and Opposition in Russia, 1906–1917 (2004).

- ^ Allan Mitchell, "The Xenophobic Style: French Counterespionage and the Emergence of the Dreyfus Affair." Journal of Modern History 52.3 (1980): 414–425. online

- ^ Douglas Porch, The French Secret Services: From the Dreyfus Affair to the Gulf War (1995).

- ^ Jules J.S. Gaspard, "A lesson lived is a lesson learned: a critical re-examination of the origins of preventative counter-espionage in Britain." Journal of Intelligence History 16.2 (2017): 150–171.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of Mi5 (London, 2009), p.21.

- ^ Calder Walton (2013). Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire. Overlook. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781468310436.

- ^ Cook, Chris. Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983) p. 95.

- ^ Miller, Toby. Spyscreen: Espionage on Film and TV from the 1930s to the 1960s Oxford University Press, 2003 ISBN 0-19-815952-8 p. 40-41.

- ^ a b c "Espionage". International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1).

- ^ "Walthère Dewé". Les malles ont une mémoire 14–18. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- ^ Adams, Jefferson (2009). Historical Dictionary of German Intelligence. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-8108-5543-4.

- ^ Hansard, HC 5ser vol 65 col 1986.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, "The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5", Allen Lane, 2009, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Jules C. Silber, The Invisible Weapons, Hutchinson, 1932, London, D639S8S5.

- ^ a b Douglas L. Wheeler. "A Guide to the History of Intelligence 1800–1918" (PDF). Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies.

- ^ Winkler, Jonathan Reed (July 2009). "Information Warfare in World War I". The Journal of Military History. 73 (3): 848–849. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0324. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 201749182.

- ^ a b Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914–1918. Long Acre, London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. pp. 2–14. ISBN 978-0-241-10864-2.

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 32.

- ^ Denniston, Robin (2007). Thirty secret years: A.G. Denniston's work for signals intelligence 1914–1944. Polperro Heritage Press. ISBN 978-0-9553648-0-8.

- ^ Johnson, John (1997). The Evolution of British Sigint, 1653–1939. London: H.M.S.O.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara W. (1958). The Zimmermann Telegram. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-32425-2.

- ^ Daniel Larsen, "British codebreaking and American diplomatic telegrams, 1914–1915." Intelligence and National Security 32.2 (2017): 256-263. online

- ^ Richard B. Spence, Trust No One: The Secret World Of Sidney Reilly; 2002, Feral House, ISBN 0-922915-79-2.

- ^ "These Are the Guys Who Invented Modern Espionage". History News Network.