List of Australian and Antarctic dinosaurs

Appearance

(Redirected from List of Australian and Antarctican dinosaurs)

This is a list of dinosaurs whose remains have been recovered from Australia or Antarctica.

Criteria for inclusion

[edit]- The genus must appear on the List of dinosaur genera.

- At least one named species of the creature must have been found in Australia or Antarctica.

- This list is a complement to Category:Dinosaurs of Australia and Dinosaurs of Antarctica.

List of Australian and Antarctic dinosaurs

[edit]Valid genera

[edit]| Name | Year | Formation | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antarctopelta | 2006 | Snow Hill Island Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Antarctica | Possessed unusual caudal vertebrae that may have supported a "macuahuitl" as in Stegouros[1] |

|

| Atlascopcosaurus | 1989 | Eumeralla Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | Only known from remains of jaws and teeth |

| |

| Australotitan | 2021 | Winton Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | The largest dinosaur known from Australia, comparable in size to large South American dinosaurs. Potentially a synonym of the contemporary Diamantinasaurus[2] |

| |

| Australovenator | 2009 | Winton Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Analysis of its arms suggests it was well-adapted to grasping[3] |

| |

| Austrosaurus | 1933 | Allaru Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Its holotype was found associated with marine shells |

| |

| Cryolophosaurus | 1994 | Hanson Formation (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian) | Antarctica | Had a distinctive "pompadour" crest that spanned the head from side to side |

|

| Diamantinasaurus | 2009 | Winton Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | May have been closely related to South American titanosaurs, suggesting they dispersed to Australia via Antarctica[4] |

| |

| Diluvicursor | 2018 | Eumeralla Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Lived in a prehistoric floodplain close to a high energy river |

| |

| Fostoria | 2019 | Griman Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Four individuals have been found in association |

| |

| Fulgurotherium | 1932 | Griman Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Fragmentary, but may have been an elasmarian[5] |

| |

| Galleonosaurus | 2019 | Wonthaggi Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian) | Its upper jaw bone resembles a galleon when turned upside down |

| |

| Glacialisaurus | 2007 | Hanson Formation (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian) | Antarctica | Basal yet survived late enough to coexist with true sauropods[6] |

|

| Imperobator | 2019 | Snow Hill Island Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Antarctica | Initially described as a basal paravian although it may potentially be an unenlagiine[7] |

|

| Kakuru | 1980 | Bulldog Shale (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Poorly known |

| |

| Kunbarrasaurus | 2015 | Allaru Formation, Toolebuc Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Preserves stomach contents containing ferns, fruit and seeds[8] |

| |

| Leaellynasaura | 1989 | Eumeralla Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian to Albian) | One referred specimen has an extremely long tail. If it does belong to this genus, it would be three times as long as the rest of the body |

| |

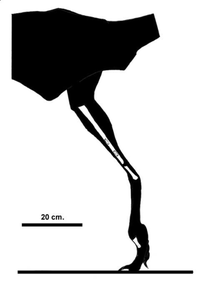

| Minmi | 1980 | Bungil Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Had long legs for an ankylosaur, possibly to help it run into bushes for protection[9] |

| |

| Morrosaurus | 2016 | Snow Hill Island Formation (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) | Antarctica | Closely related to Australian and South American ornithopods[5] |

|

| Muttaburrasaurus | 1981 | Allaru Formation?, Mackunda Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Possessed a short oval bump on its snout |

| |

| Ozraptor | 1998 | Colalura Sandstone (Middle Jurassic, Bajocian) | Potentially the oldest known abelisauroid[10] |

| |

| Qantassaurus | 1999 | Wonthaggi Formation (Early Cretaceous, Barremian) | Distinguished from other contemporary ornithopods by its relatively short dentary |

| |

| Rapator | 1932 | Griman Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Known from only a metacarpal |

| |

| Rhoetosaurus | 1926 | Walloon Coal Measures (Late Jurassic, Oxfordian) | Retains four claws on its hind feet, a basal trait |

| |

| Savannasaurus | 2016 | Winton Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian to Turonian) | May have spent more time near water than other sauropods[11] |

| |

| Serendipaceratops | 2003 | Wonthaggi Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) | Possessed a robust ulna similar to that of ceratopsians and ankylosaurs, but was likely a member of the latter group[12] | ||

| Timimus | 1993 | Eumeralla Formation (Early Cretaceous, Albian) | Potentially a tyrannosauroid.[13] If so, it would be one of the few Gondwanan members of that group |

| |

| Trinisaura | 2013 | Snow Hill Island Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) | Antarctica | The first ornithopod named from Antarctica |

|

| Weewarrasaurus | 2018 | Griman Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | Unusually, its fossils were preserved in opal |

| |

| Wintonotitan | 2009 | Winton Formation (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian) | More gracile than other contemporary titanosaurs |

|

Invalid and potentially valid genera

[edit]- Agrosaurus macgillivrayi: Although originally reported as being from Australia, it may actually be from Europe, possibly being synonymous with Thecodontosaurus.

- "Allosaurus robustus": Originally described as a new species of Allosaurus, but may actually represent a megaraptoran or abelisauroid.

- "Biscoveosaurus": Said to be a large ornithopod contemporary with Morrosaurus.

- Walgettosuchus woodwardi: It has been considered synonymous with Rapator, but too little is known of both genera to be certain.

Timeline

[edit]This is a timeline of selected dinosaurs from the list above. Time is measured in Ma, megaannum, along the x-axis.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O.; Kaluza, Jonatan; Leppe, Marcelo A.; Botelho, Joao F.; Palma-Liberona, José; Simon-Gutstein, Carolina; Fernández, Roy A.; Ortiz, Héctor; Milla, Verónica; Aravena, Bárbara; Manríquez, Leslie M. E.; Alarcón-Muñoz, Jhonatan; Pino, Juan Pablo; Trevisan, Cristine; Mansilla, Héctor; Hinojosa, Luis Felipe; Muñoz-Walther, Vicente; Rubilar-Rogers, David (9 December 2021). "Bizarre tail weaponry in a transitional ankylosaur from subantarctic Chile". Nature. 600 (7888): 259–263. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04147-1. PMID 34853468. S2CID 244799975.

- ^ Beeston, S. L.; Poropat, S. F.; Mannion, P. D.; Pentland, A. H.; Enchelmaier, M. J.; Sloan, T.; Elliott, D. A. (2024). "Reappraisal of sauropod dinosaur diversity in the Upper Cretaceous Winton Formation of Queensland, Australia, through 3D digitisation and description of new specimens". PeerJ. 12. e17180. doi:10.7717/peerj.17180. PMC 11011616.

- ^ White, Matt A.; Bell, Phil R.; Cook, Alex G.; Barnes, David G.; Tischler, Travis R.; Bassam, Brant J.; Elliott, David A. (14 September 2015). "Forearm Range of Motion in Australovenator wintonensis (Theropoda, Megaraptoridae)". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0137709. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1037709W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137709. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4569425. PMID 26368529.

- ^ Poropat, Stephen F; Kundrát, Martin; Mannion, Philip D; Upchurch, Paul; Tischler, Travis R; Elliott, David A (20 January 2021). "Second specimen of the Late Cretaceous Australian sauropod dinosaur Diamantinasaurus matildae provides new anatomical information on the skull and neck of early titanosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 192 (2): 610–674. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa173. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico Lisandro; Novas, Fernando Emilio (17 December 2019). "Osteology of the Patagonian ornithopod Talenkauen santacrucensis (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (24): 2043–2089. doi:10.1080/14772019.2019.1582562. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 155344014.

- ^ Smith, N.D.; Makovicky, P.J.; Pol, D.; Hammer, W.R. & Currie, P.J. (2007). "The Dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic Review and Synthesis" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey and the National Academies. 2007 (1047srp003): 5 pp. doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003.

- ^ Motta, M. J.; Agnolín, F. L.; Brissón Egli, F.; Novas, F. E. (2024). "Unenlagiid affinities for Imperobator antarcticus (Paraves: Theropoda): paleobiogeographical implications". Ameghiniana. doi:10.5710/AMGH.13.11.2024.3604.

- ^ Molnar, Ralph E.; Clifford, H. Trevor (2001). "An ankylosaurian cololite from Queensland, Australia". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 399–412. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. United States: Princeton University Press. pp. 226–228. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ Rauhut, O.W.M. (2005). "Post-cranial remains of ‘coelurosaurs’ (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Tanzania". Geological Magazine 142 (1): 97–107

- ^ Poropat, S.F.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Tischler, T.R.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G.H.K.; Elliott, J.A.; Elliott, D.A. (2020). "Osteology of the Wide-Hipped Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur Savannasaurus elliottorum from the Upper Cretaceous Winton Formation of Queensland, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (3): e1786836. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1786836. S2CID 224850234.

- ^ Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (1 September 2021). "Ornithischian remains from the Chorrillo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), southern Patagonia, Argentina, and their implications on ornithischian paleobiogeography in the Southern Hemisphere". Cretaceous Research. 125: 104881. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104881. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Rafael Delcourt; Orlando Nelson Grillo (2018). "Tyrannosauroids from the Southern Hemisphere: Implications for biogeography, evolution, and taxonomy". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. in press. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.09.003.