Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn | |

Gatehouse at Lincoln's Inn | |

| Website | lincolnsinn |

|---|---|

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these inns. The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple, and Gray's Inn.[1]

Lincoln's Inn is situated in Holborn, in the London Borough of Camden, just on the border with the City of London and the City of Westminster, and across the road from London School of Economics and Political Science, Royal Courts of Justice and King's College London's Maughan Library. The nearest tube station is Holborn tube station or Chancery Lane.

Lincoln's Inn is the largest Inn, covering 11 acres (4.5 hectares). It is believed to be named after Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln.

History

[edit]During the 12th and early 13th centuries, the law was taught in the City of London, primarily by the clergy. Two events ended this form of legal education: firstly, a papal bull in 1218 prohibited the clergy from teaching the common law, rather than canon law;[2] and secondly, a decree by Henry III of England on 2 December 1234 that no institutes of legal education could exist in the City of London.[3] The secular lawyers migrated to the hamlet of Holborn, near to the law courts at Westminster Hall and outside the City.[4]

As with the other Inns of Court, the precise date of founding of Lincoln's Inn is unknown. The Inn can claim the oldest records – its "black books" documenting the minutes of the governing council go back to 1422, and the earliest entries show that the inn was at that point an organised and disciplined body.[5] Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln had encouraged lawyers to move to Holborn, and they moved to Thavie's Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery, later expanding into Furnival's Inn as well.[6] It is felt that Lincoln's Inn became a formally organised inn of court soon after the earl's death in 1310.[7]

At some point before 1422, the greater part of "Lincoln's Inn", as they had become known, after the Earl, moved to the estate of Ralph Neville, the Bishop of Chichester, near Chancery Lane. They retained Thavie's and Furnival's Inn, using them as "training houses" for young lawyers, and fully purchased the properties in 1550 and 1547 respectively.[8] In 1537, the land Lincoln's Inn sat on was sold by Bishop Richard Sampson to a Bencher named William Suliard, and his son sold the land to Lincoln's Inn in 1580.[9] The Inn became formally organised as a place of legal education thanks to a decree in 1464, which required a Reader to give lectures to the law students there.[10]

During the 15th century, the Inn was not a particularly prosperous one, and the Benchers, particularly John Fortescue, are credited with fixing this situation.[11]

In 1920, Lincoln's Inn added its first female member: Marjorie Powell.

Structure and governance

[edit]

Lincoln's Inn had no constitution or fundamental form of governance, and legislation was divided into two types; statutes, passed by the Governors (see below) and ordinances issued by the Society (all the Fellows of the Inn). A third method used was to have individual Fellows promise to fulfill a certain duty; the first known example is from 1435, and starts "Here folowen certaynes covenantes and promyses made to the felloweshippe of Lyncoll' Yne".[12] The increase of the size of the Inn led to a loss of its partially democratic nature, first in 1494 when it was decided that only Benchers and Governors should have a voice in calling people to the Bar and, by the end of the sixteenth century, Benchers were almost entirely in control.[13]

Admissions were recorded in the black books and divided into two categories: Clerks (Clerici) who were admitted to Clerks' Commons; and Fellows (Socii) who were admitted to Fellows' Commons. All entrants swore the same oath regardless of category, and some Fellows were permitted to dine in Clerks' Commons as it cost less, making it difficult for academics to sometimes distinguish between the two – Walker, the editor of the Black Books, maintains that the two categories were one and the same. During the 15th century, the Fellows began to be called Masters, and the gap between Masters and Clerks gradually grew, with an order in 1505 that no Master was to be found in Clerks' Commons unless studying a point of law there.[14] By 1466, the Fellows were divided into Benchers, those "at the Bar" (ad barram, also known as "utter barristers" or simply "barristers"), and those "not at the Bar" (extra barram). By 1502, the extra barram Fellows were being referred to as "inner barristers", in contrast to the "utter" or "outer" barristers.[15]

In Lord Mansfield's time, there was no formal legal education, and the only requirement for a person to be called to the Bar was for him to have eaten five dinners a term at Lincoln's Inn, and to have read the first sentence of a paper prepared for him by the steward.[16]

Benchers

[edit]A Bencher, Benchsitter or (formally) Master of the Bench[17] is a member of the Council, the governing body of the Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn. The term originally referred to one who sat on the benches in the main hall of the Inn, which were used for dining and during moots, and the term originally had no significance. In Lincoln's Inn, the idea of a Bencher was believed to have begun far earlier than elsewhere; there are records of four Benchers being sworn in 1440.[18]

William Holdsworth and the editor of the Black Books both concluded that Benchers were, from the earliest times, the governors of the Inn, unlike other Inns who started with Readers.[19] A. W. B. Simpson, writing at a later date, decided based on the Black Books that the Benchers were not the original governing body, and that the Inn was instead ruled by Governors (or gubernatores), sometimes called Rulers, who led the Inn. The Governors were elected to serve a year-long term, with between four and six sitting at any one time.[20]

The first record of Benchers comes from 1478, when John Glynne was expelled from the Society for using "presumptious and unsuitable words" in front of the governors and "other fellows of the Bench", and a piece of legislation passed in 1489 was "ordained by the governors and other the worshipfuls of the Bench"[clarification needed]. By the late 15th century, the ruling group were the Governors (who were always Benchers) with assistance and advice from the other "masters of the Bench", and occasional votes from the entire Society.[21] The Benchers were still subordinate to the Governors, however; a note from 1505 shows the admission of two Benchers "to aid and advice for the good governing of the Inn, but not to vote". The practice of using Governors died out in 1572 and, from 1584, the term was applied to Benchers, with the power of a Governor and a new Bencher being synonymous.[22]

There are approximately 296 Benchers as of November 2013, with the body consisting of those members of the Inn elected to high judicial office, those who have sat as King's Counsel for six or seven years and some of the more distinguished "junior" barristers (those barristers who are not King's Counsel). There are also "additional benchers"—members of the Inn who have been successful in a profession other than the law, who have the rights of a normal bencher except that they cannot hold an office, such as Treasurer. In addition there are "honorary benchers", who hold all the rights of a Bencher except the right to vote and the right to hold an office. These are people of "sufficient distinction" who have been elected by the Inn, and includes people such as Margaret Thatcher, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

In common with the other Inns, Lincoln's Inn also has a "Royal Bencher"—a member or members of the Royal Family who have been elected Benchers. The present Royal Bencher is Duke of Kent who was elected after the death of the previous incumbent Princess Margaret. In 1943, when she was elected as Royal Bencher, Queen Mary became the first female Bencher in any Inn.[23] His Royal Highness Prince Andrew Duke of York was elected a Royal Bencher in December 2012.

Buildings and architectural points of note

[edit]Lincoln’s Inn’s 11-acre (4.5-hectare) estate comprises collegiate buildings, barristers’ chambers, commercial premises and residential apartments.[24] The Inn is situated between Chancery Lane and Lincoln's Inn Fields, north of Inner and Middle Temples and south of Gray's Inn. Lincoln's Inn is surrounded by a brick wall separating it from the neighbourhood; this was first erected in 1562, and it is said that Ben Jonson did some of the brickwork.[25] The only surviving part is that on the western side between the North Lawn and the Fields. As well as the major buildings discussed below, the Inn consists of: Old Square, Old Buildings, Stone Buildings and Hardwicke buildings.

First built in 1683, New Square, sometimes known as Serle Court,[26] finished in about 1697. New Square was originally named Serle's Court because it was built as a compromise between the Inn and Henry Serle over ownership of the land. A compromise was made in 1682, and Serle built 11 brick sets of chambers on three sides of the square between 1682 and 1693.[27] Alterations were made in 1843, when the open area in the middle was replaced by gardens and lawns. Because of its difficult history of ownership, some parts of the Square are still freehold, with individuals owning floors or sections of floors within the buildings.[28] The Lincoln's Inn Act 1860 was passed directly to allow the Inn to charge the various freeholders in the Square fees.[29]

Stone Buildings was built between 1775 and 1780 using the designs of Robert Taylor, with the exception of No. 7, which was completed the range in the same style in 1845.[30] The design was originally meant to be part of a massive rebuilding of the entire Inn, but this was never completed.[31] Stone Buildings were seriously damaged during The Blitz, but their external appearance remains much the same. From "within" it appears as a cul de sac rather than a square, the two ranges closed to the north with a third which originally contained the library. The eastern side along Chancery Lane and the western backing onto the North Lawn. These provide the standard layout of "staircases" of working chambers. From the North Lawn there is no access but the west range provides a fine institutional range of some distinction.

No. 10 was originally provided by the Inn to strengthen its ties with Chancery (which used to be held in the Old Hall) as the office of the Six Clerks of the Court of Chancery, with the Inn taking it back when the Clerks were abolished and the Court moved to the Royal Courts of Justice in 1882.[28] It is currently used as the headquarters of the Inns of Court & City Yeomanry, part of the Territorial Army. The Officers Mess facilities make use of the principal rooms. Lincoln's Inn has maintained a corps of volunteers in times of war since 1585, when 95 members of the Inn made a pledge to protect Queen Elizabeth against Spain. George III gave the then-temporary unit the epithet "The Devil's Own", which remains attached to the Regiment to this day.[28] There is a large War Memorial between New Square and the North lawn containing the names of the members of the Inn killed in the First World War and World War 2.

Old Square and Old Buildings were built between 1525 and 1609, initially running between numbers 1 and 26. Although 1 exists near the Gatehouse, the others now only run from 16 to 24, with some buildings having been merged to the point where the entrances for 25 and 26 now frame windows, not doorways. Hardwicke Buildings was built in the 1960s, was originally named "Hale Court", between the east range of New Square name changed in the 1990s. The buildings of Lincoln's Inn in Old Square, New Square and Stone Buildings are normally divided into four or five floors of barristers' chambers, with residential flats on the top floor. The buildings are used both by barristers and solicitors and other professional bodies.[28]

Old Hall

[edit]

The Old Hall dates from at least 1489, when it replaced the smaller "bishops hall". The Old Hall is 71 feet long and 32 feet wide, although little remains of the original size and shape; it was significantly altered in 1625, 1652, 1706 and 1819.[32] A former librarian reported that it was "extensively remodelled" by Francis Bernasconi in 1800. This remodelling led to the covering of the oak beams with a curved plaster ceiling, "a most barbarous innovation".[32] The weight of the plaster created the risk that the roof would collapse, and between 1924 and 1927 Sir John Simpson dismantled the entire hall, straightening warped timbers, removing the plaster, replacing any unserviceable sections and then putting the entire hall back together. It was reopened on 22 November 1928 by Queen Mary.[33]

As well as its use for revels, moots and feasts, the Old Hall was also used as a court. The Master of the Rolls sat there between 1717 and 1724 while the Rolls Court was being rebuilt, and Lord Talbot used it as a court in 1733. From 1737 onward it was used to house the Court of Chancery, a practice that ended with the opening of the Royal Courts of Justice.[32] The Hall's most famous use as a court is in the start of Charles Dickens' Bleak House, which opens with "London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall".[33] It is now used for examinations, lectures, social functions[34] and can be hired for private events.[35] In 2010 the Hall was refurbished and its Crypt was improved and made more accessible by the installation of a staircase from the outside.

Chapel

[edit]

The first mention of a chapel in Lincoln's Inn comes from 1428. By the 17th century, this had become too small, and discussions started about building a new one in 1608.[36] The current chapel was built between 1620 and 1623 by Inigo Jones, and was extensively rebuilt in 1797 and again in 1883. Other repairs took place in 1685, after the consultation of Christopher Wren, and again in 1915. The chapel is built on a fan-vaulted, open undercroft[37] and has acted (sometimes simultaneously) as a crypt, meeting place and place of recreation. For many years only Benchers were allowed to be buried in the Crypt, with the last one being interred on 15 May 1852. Before that, however, it was open to any member or servant of the society; in 1829 a former Preacher was interred, and in 1780 William Turner, described as "Hatch-keeper and Washpot to this Honble. Society", was buried.[38]

The chapel has a bell said to date from 1596, although this is not considered likely. Traditionally, the bell would chime a curfew at 9 pm, with a stroke for each year of the current Treasurer's age. The bell would also chime between 12:30 and 1:00 pm when a Bencher had died.[36] Inside the chapel are six stained glass windows, three on each side, designed by the Van Linge family.[39]

The chapel's first pipe organ was a Flight & Robson model installed in 1820.[40] A substantial William Hill organ replaced it in 1856; a model designed at the peak of his skill, with thick lead and tin pipes,[41] a set of pedals, and three manuals.[40] During its service years it was rebuilt nine times, the final overhaul carried out in 1969. In the 2000s the organ, increasingly unreliable, was seen to have little unaltered initial material, with little hope of returning it to original condition, and it was replaced with a Kenneth Tickell model, the new organ installed during 2009–2010.[40]

The chapel is used for concerts throughout the year.

Great Hall

[edit]

The Great Hall, or New Hall, was constructed during the 19th century. The Inn's membership had grown to the point where the Old Hall was too small for meetings, and so the Benchers decided to construct a new hall, also containing sizable rooms for their use, and a library. The new building was designed by Philip Hardwick, with the foundation stone laid on 20 April 1843 by James Lewis Knight-Bruce, the Treasurer.[42]

The building was completed by 1845, and opened by Queen Victoria on 30 October.[34] The Hall is 120 feet (37 metres) long, 45 ft (14 m) wide, and 62 ft (19 m) high, much larger than the Old Hall.[43] The Great Hall is used for the call to the Bar, as a dining place and for concerts arranged through the Bar Musical Society.[34]

The lower ground floor was divided by a mezzanine in 2007 and the upper part became the Members Common Room for informal dining and with a lounge. It replaced the Junior Common Room, Barristers Members Room and Benchers Room as a social facility. In effect it is a club providing bar and restaurant facilities for all "entitled" persons, meaning members of the Inn and its bona fide tenants.

Library

[edit]

The Library was first mentioned in 1471, and originally existed in a building next to the Old Hall before being moved to a set of chambers at No. 2 Stone Buildings in 1787. A bequest by John Nethersale in 1497 is recorded as an early acquisition.[44]

The current Library was built as part of the complex containing the Great Hall, to the designs of Hardwick and was finished in 1845 being formally opened by Queen Victoria. At this point it was 80 feet long, 40 feet wide and 44 feet high.[45] It was extended, almost doubled, in 1872 by George Gilbert Scott in the same style. The ground floor contained a Court room which became part of the Library facilities when the Court of Chancery moved out of the Inn in the 1880s. It has since 2010 been utilised as a lecture room and during the developments of 2016 to 2018 became the 'interim' Members Common Room.

The Library contains a large collection of rare books, including the Hale Manuscripts, the complete collection of Sir Matthew Hale, which he left to the Inn on his death in 1676. The Library also contains over 1,000 other rare manuscripts, and approximately 2,000 pamphlets.[46] The total collection of the Library, including textbooks and practitioners works, is approximately 150,000 volumes. The collection also includes a complete set of Parliamentary records.[47] The Library is open to all students and barristers of Lincoln's Inn, as well as outside scholars and solicitors by application.

The Library is primarily a reference library, so borrowing is restricted. The only other lending service available is offered by Middle Temple Library, which permits barristers and students of any Inn, on production of suitable ID, to borrow current editions of textbooks that are not loose-leaf – but not any other material – half an hour before closing for return by half an hour after opening the following day.[48]

Gatehouse

[edit]

The Gatehouse from Chancery Lane is the oldest existing part of the Inn, and was built between 1518 and 1521.[49] The Gatehouse was mainly built thanks to the efforts of Sir Thomas Lovell, the Treasurer at the time, who provided at least a third of the funds and oversaw the construction itself—as a result, his coat of arms hang on the gate, along with those of the Earl of Lincoln and Henry VIII (the king at the time).[50]

The Gatehouse is a large tower four stories high and features diagonal rows of darker bricks, along with a set of oak gates that date from 1564. The Gatehouse was restored in 1695 and again between 1967 and 1969—the arms of the Treasurers for those years (Lord Upjohn, John Hawles and Princess Margaret) were added to the inwards side of the Gatehouse itself.[51] Minor repairs also took place in 1815, when the three Coats of Arms were repaired and cleaned.[52]

New Square Lawn

[edit]The New Square Lawn is surrounded by the block of New Square. It is bordered by the Lincoln Inn chambers, and is visible from the western Gatehouse. Centred on the New Square Lawn is Jubilee Fountain. After the original fountain from 1970 was removed, William Pye installed the new Jubilee fountain in 2003, to celebrate Queen Elizabeth's Golden Jubilee.[53] The construction of the fountain was funded by David Shirley. The Jubilee fountain is a two tier fountain centered in New Square. The top level of the fountain creates arches in the air with the water, and the lower level has complementary tiny fountains. A photo of the fountain can be found on the designer's website.

East Terrace Underground development, New Library and New Teaching Facilities

[edit]The Inn self-funded a major improvement and extension of its facilities between 2016 and 2018. The Inn being a conservation area and consisting of listed buildings could not simply add modern structures within the precincts without considerable difficulty of their impact on the current layout and planning objections by interest groups, as well indeed from members of the Inn. The improvement requirements for the Library and teaching activities were partly addressed by demolition of the Under Treasurer's House on the north side of the Library, which was a post-WW2 building, replacing it with an extension to the Reading Rooms and Book Stack. The solution of providing a 150-seat Lecture Theatre and Tutorial Rooms was to exploit the space under the large east terrace of the Great Hall.

The Inn decided to name the new education suite the Ashworth Centre after Mercy Ashworth, one of the first women to be called to the bar by Lincoln's Inn. On 13 December 2018, HM Queen Elizabeth II along with the Duke of York (Royal Bencher of the Inn) officially opened the Ashworth Centre and re-opened the Great Hall following its renovation. The Great Hall was originally opened by Queen Victoria in 1845.

Coat of arms

[edit]

For many years, the Inn used the arms of the 3rd Earl of Lincoln as their own; in blazon, a "lion rampant purpure in a field or", which is a purple lion on a gold field. Around 1699, Sir Richard Holford discovered the Inn's own coat of arms on a manuscript, granted to them in 1516. The arms are "azure seme de fer moline or, on a dexter canton or a lion rampant purpure". Following validation using some heraldry books, the arms were placed first in the council chamber and then in the library. Since then, they have been used continuously in Lincoln's Inn.[54]

Notable members

[edit]Political alumni

[edit]- Margaret Thatcher (1953), former and first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, specialised in taxation law;

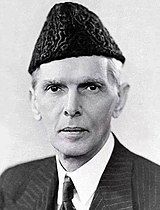

- Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876), founder and first Governor General of Pakistan;

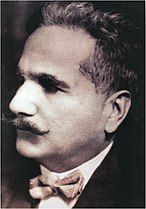

- Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1877), Muslim poet, philosopher and politician and National poet of Pakistan

- H. H. Asquith (1852), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith

- Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, former President and the Prime Minister of Pakistan;

- William Ewart Gladstone (1809), four times Prime Minister of the United Kingdom;

- Chaim Herzog (1918), sixth President of Israel;

- William Pitt the Younger, twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1759);

- Gnanendramohan Tagore, first Asian to be called at the bar;

- Shankar Dayal Sharma (1918), 9th President of the Republic of India;

- Azlan Shah of Perak, former Lord President of Malaysia, Sultan of Perak Darul Ridzuan;

- Tony Blair, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom;

- Basdeo Panday, fifth Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago

- Notable political alumni include:

Preachers of Lincoln's Inn

[edit]

The office of Preacher of Lincoln's Inn or Preacher to Lincoln's Inn is a clerical office in the Church of England.[55] Past incumbents include:

- John Donne (1616–1622)[56]

- Reginald Heber (1822–?)[57]

- Edward Maltby (1824–1833)[58]

- William Van Mildert (1812–1819)[59]

- Henry Wace[60]

- William Warburton (1746–?)[61]

- Derek Watson

- Hastings Rashdall[62]

Other organisations based in the Inn

[edit]

- The volunteer militia, later formalised (1908) within the Territorial Army, and today forming the headquarters of 68 Signal Squadron.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Honorable Society of Lincoln's Inn". lincolnsinn.org.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Bellot (1902) p. 32

- ^ Douthwaite (1886) p.2

- ^ "Uncommon counsel (2): Barts, butchers and barristers". Counsel. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Barton (1928) p.7

- ^ Barton (1928) p.256

- ^ Spilsbury (1850) p.32

- ^ Barton (1928) p.257

- ^ Barton (1928) p.258

- ^ Ringrose (1909) p.81

- ^ Pulling (1884) p.142

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.247

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.256

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.243

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.250

- ^ Lord Mansfield: A Biography of William Murray 1st Earl of Mansfield 1705–1793 Lord Chief Justice for 32 years. Heward, Edmund (1979), Chichester: Barry Rose (publishers) Ltd., ISBN 0-85992-163-8, p. 13

- ^ Rozenberg, Joshua (19 October 2008). "Some jolly good fellows". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Pearce (1848) p.133

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.242

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.245

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.248

- ^ Simpson (1970) p.249

- ^ "Lincolns Inn History – Benchers". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "The Estate". Lincoln's Inn. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Edward (1860) p.96

- ^ Spilsbury (1850 p.35

- ^ Spilsbury (1850 p.81

- ^ a b c d "Lincolns Inn History – Chambers". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Catt, Richard (1997). "Small urban spaces: part 8 – protecting London squares". Structural Survey. 15 (1). Emerald: 34–35. doi:10.1108/02630809710164715. ISSN 0263-080X.

- ^ Spilsbury (1850) p. 36

- ^ Spilsbury (1850 p. 83

- ^ a b c Barton (1928) p.261

- ^ a b "Lincoln's Inn History – Old Hall". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ a b c "Lincolns Inn History – Great Hall". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "United Kingdom: Lincoln's Inn : Events Hire". hirespace.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ a b "The Chapel". The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Teller, Matthew (2004). The Rough Guide to Britain. Rough Guides. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-84353-301-6. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Barton (1928) p.263

- ^ Barton (1928) p.264

- ^ a b c "AES London 2011 Organ Recital". Audio Engineering Society. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Thistlethwaite, Nicholas (2009). The making of the Victorian organ. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-521-66364-9.

- ^ Barton (1928) p.267

- ^ Barton (1928) p.268

- ^ page 48 'The Library of Lincoln's Inn' University of London; Rye, Reginald Arthur, 1876–1945; University of California Libraries (1908), "The libraries of London: a guide for students", Nature, 78 (2020), London, University of London: 244, Bibcode:1908Natur..78S.244., doi:10.1038/078244c0, hdl:2027/gri.ark:/13960/t4rj78190, S2CID 37866614, retrieved 23 February 2014

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Edward (1860) p.97

- ^ "Lincolns Inn History – Rare books and manuscripts". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "Lincolns Inn History – Scope of the collection". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ "Services". Lincolnsinn.org.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Loftie (1895) p.175

- ^ Barton (1928) p.262t

- ^ "Lincolns Inn History – The Gate House". Lincoln's Inn. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Ringrose (1909) p.78

- ^ "Jubilee Fountain – Work William Pye Water Sculpture". Williampye.com. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Pearce (1848) p.135

- ^ online-law.co.uk Archived 15 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jessopp, Augustus (1888). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 15. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Overton, John Henry (1891). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 25. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Gordon, Alexander (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Courtney, William Prideaux (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ "Aleph main menu". www.kcl.ac.uk.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 59. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Rayner, Margaret J. (2005). The Theology of Hastings Rashdall: A Study of His Part in Theological Debates During His Lifetime (PhD thesis). University of Gloucestershire. p. 13. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barton, Dunbar Plunket; Benham, Charles; Watt, Francis (1928). The Story of the Inns of Court. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 77565485.

- Douthwaite, William Ralph (1886). Gray's Inn, Its History & Associations. Reeves and Turner. OCLC 2578698.

- Draper, Warwick (1906). "The Watts Fresco in Lincoln's Inn". Burlington Magazine. 9 (37). ISSN 0951-0788.

- Loftie, W. J. (1895). The Inns of Court and Chancery. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 592845.

- Pearce, Robert Richard (1848). History of the Inns of Court and Chancery: With Notices of Their Ancient Discipline, Rules, Orders, and Customs, Readings, Moots, Masques, Revels, and Entertainments. R. Bentley. OCLC 16803021.

- Pulling, Alexander (1884). The Order of the Coif. William Clows & Sons Ltd. OCLC 2049459.

- Ringrose, Hyacinthe (1909). The Inns of Court: An Historical Description. Oxford: R.L. Williams. OCLC 60732875.

- Simpson, A. W. B. (1970). "The Early Constitution of the Inns of Court". Cambridge Law Journal. 34 (1). Cambridge University Press. ISSN 0008-1973.

- Spilsbury, William Holden (1850). Lincoln's Inn: its ancient and modern buildings: with an account of the library. W. Pickering. OCLC 316910934.

- Stanford, Edward (1860). Stanford's New London Guide. Stanford. OCLC 60205994.