Léon Germain Pelouse

Léon Germain Pelouse (1 October 1838 – 31 July 1891) was a largely self-taught painter born in Pierrelaye, France.[1] His work was most often said to descend from that of Corot and Daubigny,[2] but was from the beginning unique in its depiction of an often stark, obsessively detailed nature largely devoid of human figures. At the time of his death at age 52 in Paris, Pelouse was "considered one of the great landscape painters of his time."[3]

Life and career

[edit]Pelouse was born and spent his first eleven years in the small village of Pierrelaye, into a family of little means.[4] In 1849 his family moved to Paris and, five years later, on the death of his father, Léon-Germain, having to earn a living, at sixteen began working as a traveling salesman for his uncle, a draper.[5][6]

He began painting as an amateur and took some evening classes.[5] His professional painting career began at age twenty-seven, with the acceptance and exhibition of his Les Environs de Précy at the Paris Salon of 1865.[7] The work made a strong impression, especially coming from a painter without the usual Academic education. "From the beginning," wrote Albert Patin de La Fizelière, Pelouse displayed "the easy grace, brilliance, and suppleness of execution that have since been admired in his canvases."[5]

Inspired by this success, despite the offer of a partnership with his uncle[6] and against the opposition of his mother, with whom he quarreled, Pelouse left his sales job to become a painter full-time. He traveled to Brittany, and there, inspired by nature around Pont-Aven, Concarneau, and Rochefort-en-Terre, painted landscapes that were exhibited at the Paris Salon in following years.[8] From 1873, when he received a second-class medal at the Salon, for Vallée de Cernay, he gained mounting success and critical acclaim.[5] In 1876, his Une Coupe de bois à Senlisse received a first-class medal, "a reward which for thirty years had not been given to a landscape painter."[9]

Pelouse became a prolific and sought-after artist. In 1884, Eugène Montrosier wrote, "Díaz de la Peña produces paintings like apple trees give apples, it has been said. One could write as much of M. Pelouse who, without a master, by the sole force of his will, has succeeded in a few years to take one of the first places among modern landscape painters"[10] and to become "one of the most distinguished painters of the young school."[11]

Pelouse's fame spread to North America. Scribner's Monthly, reviewing the Paris Salon of 1878, wrote that Pelouse's "style is impressive, his pictures rich and daring in color, the execution marked by the greatest breadth and freedom of handling....he shows an imagination equal to that of Daubigny."[12] In the 1880s, Pelouse was "the most prestigious" of the French artists whose work was imported to Canada by W. Scott & Sons of Montreal.[13][14]

In 1878 Pelouse was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. In 1889 he was awarded a gold medal at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. From 1884-90 he served on the jury of the Paris Salon.[8][3] Georges Lanoë-Villène says that Pelouse "was all-powerful on the jury."[15]

Pelouse died in 1891, at age 52, of complications from diabetes.[16][17] He was interred in a vault in the cemetery of Le Pré-Saint-Gervais in Paris.[18] At his funeral, William-Adolphe Bouguereau spoke of Pelouse's character:

"What a frank, loyal, and cheerful nature! How happy we felt to be with him. What inexhaustible verve, what fine wit, what benevolence and kindness! His pupils, who lived next door to him in the country, can tell what treasures this heart contained. And in difficult times, how good and consoling was his faithful friendship! His sensitive soul was indignant at injustices. With what gratitude he cherished the memory of the slightest services that others had been able to render him!"[19]

A posthumous retrospective of more than 250 of his works, inaugurated by the President of the Republic, Sadi Carnot, was exhibited in 1892 at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1897, a monument to his memory, surmounted by a bronze bust by Alexandre Falguière, was erected and dedicated in Cernay.[3]

The French government bought many of his works, now in the collections of numerous museums, including the Musée d'Orsay,[20][21] the Musée Malraux, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes.[22] His works are also held in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and in museums in San Francisco, Ghent, Oslo, Munich, and Sydney.

École de Cernay; students

[edit]

During the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, Pelouse enlisted in the national guard. During his service, he spent time in the town of Cernay-la-Ville, near Paris, and experienced a powerful attraction to the surrounding scenery. After the war, in 1871, Pelouse walked on foot from Paris to Cernay, which had been ransacked by the Prussians, and took lodgings at the inn of Léopold Lequesne.[6] In 1876, with his wife and stepson, he rented a small house on the village square.[23] He would eventually have numerous ateliers in the area, including "a barn next to the tiny church that the Rothschilds, those gold powerhouses, had restored."[24][25][26]

"Poverty made him frugal, handy, and ingenious...he made his own clothes and even his hats and shoes; he wanted to save his money for brushes and paints."[27] It was Pelouse's habit to wear a peasant blouse and sabots, setting out with his easel and paints at daybreak, "often forgetting meals and only returning a long time after sunset."[6] "As Claude Monet did in 1867 with Women in the Garden, Pelouse did not hesitate to set up large-format canvases in the countryside in order to be able to paint them entirely en plein air."[28] He would

set up, like a theater set, a whole installation: tent, boards, parasols, easels, in woods, or plains, or along the course of a stream, carrying everywhere with him and without help a genuinely mobile atelier. Once camped like this, the work began, and nothing and no one could tear him away from the study undertaken before he had delivered the final brushstroke. His determination was such that, wishing to complete a study of snow at Cernay in 1872, he spent part of the day without thinking for a moment of the horrible cold that enveloped him; the next day, he learned from the newspapers that the thermometer had dropped to 24 degrees below zero![29]

Pelouse, known for "his natural bonhomie, his insouciance and his good-natured gaiety,"[5] was visited by other artists, including Henri Harpignies, Louis Français, Jules Breton, Émile Breton, Charles Ferdinand Ceramano, Winslow Homer, Theodore Robinson, and Peder Severin Krøyer,[30] and attracted an international coterie of pupils. They socialized in the welcoming inns of Place de Cernay-la-Ville, in particular the establishment of Léopold Lequesne, which became known as Au Rendezvous des Artistes.[31][32] Lequesne's wife was called "the mother of artists" (la mère des artistes).[6] Pelouse and this colony of colleagues and students became known as the École de Cernay, of which Pelouse was the acknowledged chef de file[33] and "le plus Cernaysien" of landscape painters.[28]

Often compared and contrasted to the realist landscape painters of the Barbizon school, for his paintings of Brittany Pelouse was "counted among the artists known as 'Les Barbizon bretons'".[8]

Paradoxically, the largely self-taught Pelouse became the mentor and teacher of many painters, who came from as far as Sweden and Canada to study and paint outdoors with him in the fields and woods outside Cernay-la-Ville. These included Madame Annaly, Érnest Baillet, Harriet Backer, Émile Charles Dameron, Nicolas Dracopolis, Allan Edson,[34] Eugène Galien-Laloue, Edouard Gendrot, Léon Joubert, Kitty Lange Kielland, Adolphe-Frédéric Lejeune, Émile Le Marié des Landelles, Flavien-Louis Peslin, Albert Rigolot, Louis Telingue, and Percy Franklin Woodcock.[35][36][37][13][38][11][30]

Pelouse welcomed female artists, including Norwegian Kitty Lange Kielland[39] and her compatriot and friend Harriet Backer. They accompanied Pelouse on an excursion to Rochefort-en-Terre, in Brittany. Backer later recalled:

Léon Pelouse had proposed to us two women that we spend the summer in his company in a location he had discovered and kept secret: it was a way of getting a jump on new and original subjects, instead of the well-worn themes exhibited at the Salon...Under a discreet disguise, we set out with Pelouse, his wife, and two of his male pupils...Pelouse is the most natural man I've ever met...I'm sure if you were to arrive one evening while we're at the table, you'd be extremely surprised. Pelouse and Érnest Baillet each scream louder than the other to make themselves heard, to the point that one wonders if they'll come to blows—then it all ends with outbursts of laughter, so loud we have to cover our ears.[40]

In the spring and summer of 1879, the Danish painter Peder Severin Krøyer stayed at Pelouse's home in Cernay, and painted Le Déjeuner des artistes à Cernay-la-Ville, which captures the social scene at Léopold Lequesne's inn. Pelouse can be seen standing at right, wearing a hat and smoking, framed by the glow of light from the window.[41][42]

Other locations

[edit]While based in Cernay, Pelouse made numerous excursions to paint the scenery at Pont-Aven, Rochefort-en-Terre, Concarneau, Honfleur, Trouville, Marlotte in the Forest of Fontainebleau, and beyond France to Belgium and Holland.[32]

In 1884, the Pelouse family left Cernay to return to Paris. Between 1886 and 1888, the artist painted near Besançon, in the Loue valley dear to Gustave Courbet. About sixty paintings date from this period.[32]

Family

[edit]

Received at the Château de Rottembourg in Montgeron by the collector and businessman Ernest Hoschedé, Pelouse met the widow of a Belgian, Ernest Raingo (d. 1871), née Lucy-Alexandrine Fossey (1842-1895). Pelouse and Lucy married on September 8, 1874.[5][43]

Ernest Raingo's sister Alice was the wife first of Hoschedé, and then, the year after Hoschedé's death in 1891, of Claude Monet.

In 1890, in failing health, Pelouse officially adopted Lucy's son by Ernest Raingo, Jean, who took the name Raingo-Pelouse.[44] Jean's sons Germain, Bernard and Pierre also took this hypehated name. Germain Raingo-Pelouse (1893-1963) became a noted artist, but never knew his grandfather and namesake, as their lifespans did not overlap.[45] Germain Raingo-Pelouse's aunt was Alice Hoschedé, and his uncle, by her second marriage, was Claude Monet.

Themes and reception

[edit]-

Le Plateau de la Montjoie à Mortain, 1872, Musée d'Orsay

-

La Mare aux hérons (detail), before 1875, private collection

-

Le passage de Lanriec à Concarneau, effet de lune, 1878, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen

-

Un coin de Cernay en janvier, after 1879, by 1887, Metropolitan Museum

Renate Treydel in the Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon notes that Pelouse

takes his cue from Camille Corot, Henri Joseph Harpignies, Charles-François Daubigny and Camille Bernier, but his main source of inspiration is nature, in which he develops a keen sense of the choice of motifs. At the Salon debut in Paris in 1865, he was attested to a high degree of technical virtuosity and natural talent, as well as praised for his light-handed, loose brushwork. He prefers unspectacular, tranquil views, often just trees, inconspicuous things like earth or moss, lush, wild nature with impenetrable thickets, and lonely villages...Pelouse works intuitively, quickly and exclusively in nature...The sober composition of Banc de rochers à Concarneau (1880, Brest) is considered a bold and early anticipation of the art of Charles Cottet due to its omission of picturesque features and a gloomy coloring.[8]

A few years after Pelouse's death, Robert Alan Mowbray Stevenson wrote that Pelouse sought to recapture a primal vision of nature:

Pelouse...used to say that the gift of the naturalist lay in the power of recreating the eye of childhood. When the child first sees—before he ean walk, before he can what all these coloured spots of various shapes and strengths may mean—he receives from a field of sight an impression of the values of colour and the forces of definition utterly unadulterated by knowledge of distance, depth, shape, utility and the commercial, religious, or sexual importance of objects. Indeed, he is not biased by that chief disturber of impression, the knowledge that any objects exist; in fact, he sees men as trees walking. He sees patterns, and it takes him years to know what these patterns, these changing gradations, these varying smudges signify, and when he has learnt that, in proportion as he has succeeded, so he has ceased to know the original vision, and to perceive mentally the signs by which he originally determined the truth.[46]

After the death of Charles-François Daubigny in 1878, Pelouse was considered to have taken Daubigny's place as the foremost landscape painter in France.[47] After Pelouse's death "at his height as an artist,"[48] the posthumous exhibit of his work in 1892 received wide attention, including in the United States, where John Preston Beecher in The Collector called Pelouse "one of those geniuses who have had no master in art except nature...a great painter," and "a worthy rival of that magician of the palette and brush, Théodore Rousseau."[49]

Celebrated in life and in death, in subsequent decades Pelouse's fame faded as the realist landscape painters of the Barbizon school and the École de Cernay were supplanted by the rapidly evolving modern schools of French art.

Gallery

[edit]-

Banc de rochers à Concarneau, 1880, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Brest

-

Landscape with storm clouds, 1881, private collection

-

Grandcamp à marée basse, 1884, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne

-

Sunrise or sunset with lone figure, c. 1884-1887, private collection

-

Forest at dusk, 1885, private collection

-

Paysage dans les environs de Saint-Jean-le-Thomas (Normandie), 1885, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent

-

Riverside village at dusk, 1888, private collection

-

Étang forestier, n.d., private collection

-

Forêt de Fontainebleau, n.d., private collection

-

Landscape, n.d., NaM, Oslo

-

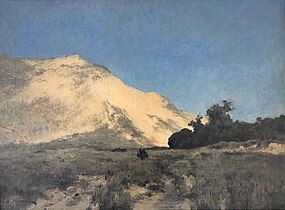

Mountain and dune, n.d., private collection

References

[edit]- ^ Champlin (1892), "Pelouse, Léon Germain"

- ^ Gonzague Privat. "L'Exposition du Paysagiste Pelouse à l'École des Beaux-Arts", Gazette anecdotique, littéraire, artistique et bibliographique, March 15, 1892, p 132.: Pelouse's work "has an enviable place on the luminous path of Corot and Daubigny."

- ^ a b c Schubert (2001), p. 129.

- ^ Gille (1894), p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f Schubert (2001), p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e Legrand (1892), p. 45.

- ^ Fresneau (2007), p. 99.

- ^ a b c d Treydel (2017).

- ^ Montrosier (1884), p. 102.

- ^ Montrosier (1884), p. 101.

- ^ a b Montrosier (1884), p. 63.

- ^ "Art at the Paris Exposition", Scribner's Monthly, vol. 17, no. 2, December 1878, p. 277.

- ^ a b Sicotte (2005), p. 117.

- ^ Sicotte (2002).

- ^ Lanoë-Villène (1905), p. 260.

- ^ de Lassus (2016), p. 41.

- ^ "Nécrologie", La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité: supplément à la Gazette des beaux-arts, August 8, 1891, p. 215: "Il a succombé à une maladie diabétique dont il était atteint depuis cinq ans."

- ^ "Nécrologie",Le Radical, August 2, 1891, p. 2.

- ^ Bouguereau's eulogy is quote by Gille (1894), pp. 240-241.

- ^ "Collections du musée d'Orsay: Léon Germain Pelouse". www.musee-orsay.fr. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Aux couleurs de la mer : Paris, Musée d'Orsay, 6 novembre 1999-16 janvier 2000, Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1999, p. 65.

- ^ "Pelouse Léon Germain", Portail des collections des musées de France, Paris, Joconde, 2013

- ^ de Lassus (2016), pp. 41-42

- ^ Riotor (1903), p. 295.

- ^ In 1873, Baroness Charlotte de Rothschild bought the ruins of the Vaux-de-Cernay Abbey and set about restoring them, and became a patron of the artists of the region. See Dutat (2016), p. 17, and de Lassus (2016), p. 60-61.

- ^ Legrand (1892), p. 46: "An atelier had become essential. Pelouse converted a barn; the bay window, even the chandelier, were his ingenious work."

- ^ Catalogue des tableaux de L.-G. Pelouse (1892), preface by Philippe Gille, p. 25.

- ^ a b Schubert (2001), p. 122.

- ^ Catalogue des tableaux de L.-G. Pelouse (1892), preface by Philippe Gille, p. 26.

- ^ a b "Léon Germain Pelouse". www.cernaylaville.fr. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Dutat (2016), p. 24-25.

- ^ a b c de Lassus (2016), p. 42.

- ^ de Lassus (2016), p. 40.

- ^ Hopkins, John Castell, editor. Canada: an Encyclopædia of the Country, Toronto: Linscott, vol. IV, p. 403 : "Pelouse…considered Edson his best and favourite pupil."

- ^ de Lassus (2016), p. 43.

- ^ "Léon Germain Pelouse". association-peintres-en-vallee-de-chevreuse.fr. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Sicotte (2002), p. 22.

- ^ Béland (2017).

- ^ Gunnarsson, Torsten. Nordic Landscape Painting in the Nineteenth Century, Yale University Press, 1998, p. 159: Kielland learned from Pelouse "not only to work in front of the subject but also to try to retain something of the character of the first sketch in the finished painting."

- ^ Dutat (2016), p. 25.

- ^ Aas, Tanja (August 9, 2022). "Close to: Léon Germain Pelouse (1838-1891)". skagenskunstmuseer.dk.

- ^ Regarding the location depicted, see Dutat (2016), p. 25.

- ^ Legrand (1892), p. 46 suggests that Lucy was destitute: "Rich prospects were presented to him [Pelouse], but he listened only to his heart, and he married a young widow who had for dowry only a dearly loved son."

- ^ "Adoption", Le Droit: journal des tribunaux, November 5, 1890, p. 1057: "La première chambre de la Cour d’appel, présidée par M. Périvier, premier président, a confirmé le jugement du Tribunal de la Seine, portant qu'il y a lieu à l’adoption de Lucien-Jean-Léon Raingo, par Germain-Léon Pelouse."

- ^ "Généalogie familiale développée par Jean Raingo-Pelouse," Le Gaulois, August 4, 1908.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Alan Mowbray. The Art of Velasquez, London:George Bell and Sons, 1895, pp. 113-114.

- ^ La Chronique universelle, artistique, politique, scientifique, littéraire, illustrée, vol. 2, no. 11, July supplement, 1891, p. iv: Pelouse "laisse un vide très sensible dans l'école française de paysage. Depuis la mort de Daubigny, il avait pris en quelque sorte la place de chef laissée vacante."

- ^ Catalogue des tableaux de L.-G. Pelouse (1892), preface by Philippe Gille, p. 26.

- ^ Beecher, John Preston. "Babble of the Boulevard", The Collector, vol. 3, no. 11 (April 1, 1892), p. 170.

Bibliography

[edit]- Béland, Mario. "Woodcock et la paysannerie française", Cap-aux-Diamants: la revue d'histoire du Québec, no. 129, 2017, p. 53.

- Catalogue des tableaux de L.-G. Pelouse réunis à l'École nationale des beaux-arts, quai Malaquais, with a preface and biographical note by Philippe Gille, Paris: École nationale des beaux arts, 1892.

- Champlin, John Denison. Cyclopedia of painters and paintings, New York: Scribner, 1892.

- de Lassus, Priscille. "Pelouse, Chef de File" and "L’Abbaye des Vaux de Cernay" in Vallée de Chevreuse: le Petit Moulin des Vaux de Cernay, L'Object d'Art Hors-Série no. 106, Dijon: Éditions Faton, Sept. 2016.

- Dutat, Dimitri. "La colonie de Cernay, trois générations d’artistes" and "La Vallée de Chevreuse, une Destination à la Mode" in Vallée de Chevreuse: le Petit Moulin des Vaux de Cernay, L'Object d'Art Hors-Série no. 106, Dijon: Éditions Faton, Sept. 2016.

- Fresneau, Estelle. Pont-Aven : du paysage à l'œuvre, Pont-Aven: Musée de Pont-Aven, 2007.

- Gille, Philippe. Causeries sur l'art et les artistes, Paris: Ancienne Maison Michel Lévy, 1894.

- Harambourg, Lydia. Cernay, une étape pour les paysagistes de Barbizon, catalogue on the exposition at the Centre Culturel Léon-Germain Pelouse de Cernay-la-Ville, 1997.

- Lacambre, Geneviève. Le Musee du Luxembourg en 1874. Peintures, Paris: Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 1974.

- Lanoë-Villène, Georges. Histoire de l'école française de paysage depuis Chintreuil jusqu'à 1900, Nantes: Société nantaise d'éditions, 1905.

- Legrand, Julien. "Causerie: L.-G. Pelouse", Journal des artistes, February 14, 1892, pp. 45-46.

- Levesque, Patrick and Stéphan, Édouard. Léon Germain Pelouse, 1838-1891, Catalogue Raisonné, Cernay-la-Ville: Chez l'Auteur, 2005.

- Montrosier, Eugène. Les artistes modernes, vol. 4, Paris: H. Launette, 1884, p. 63, pp. 101-104 and 1 unnumbered plate (Janvier à Cernay).

- Riotor, Léon. "Léon-Germain Pelouse: Exposition de Mars 1892" (pp. 291-296) in Les arts et les lettres, vol. 2, Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1903.

- Sicotte, Hélène (2002). Le Rôle de la Vente Publique dans l'Essor de Commerce et d'Art à Montréal au XiXe Siècle: Le cas de W. Scott & Sons ou comment le marchand d'art supplanta l'encanteur", Journal of Canadian Art History/Annales d'histoire de l'art Canadien, Vol. 23, No. 1/2, 2002, pp. 6-33.

- Sicotte, Hélène (2005). "Suzor-Coté chez W. Scott & Sons de Montréal: Du rôle de l'exposition particulière dans la consécration d'une carrière d'artiste", Journal of Canadian Art History/Annales d'histoire de l'art Canadien, Vol. 26, 2005, pp. 108-125.

- Schubert, Philippe and Schubert, France. Les Peintres de la Vallée de Chevreuse, Paris: Les Éditions de l’Amateur, 2001.

- Treydel, Renate. "Pelouse, Léon Germain (Léon)" in Allgemeines KünstlerLexikon, Die Bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, vol. 95, p. 19, Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017.