Kundun

| Kundun | |

|---|---|

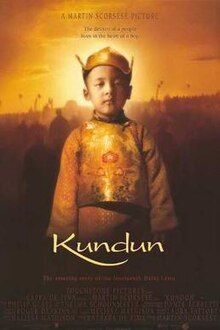

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Written by | Melissa Mathison |

| Produced by | Barbara De Fina |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

| Music by | Philip Glass |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution (United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland) Canal+ Image International (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $28 million[2] |

| Box office | $5.7 million[2] |

Kundun is a 1997 American epic biographical film written by Melissa Mathison and directed by Martin Scorsese. It is based on the life and writings of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, the exiled political and spiritual leader of Tibet. Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong, a grandnephew of the Dalai Lama, stars as the adult Dalai Lama, while Tencho Gyalpo, a niece of the Dalai Lama, appears as the Dalai Lama's mother.

"Kundun" (སྐུ་མདུན་ Wylie: sku mdun in Tibetan), meaning "presence", is a title by which the Dalai Lama is addressed. Kundun was released only a few months after Seven Years in Tibet, sharing the latter's location and its depiction of the Dalai Lama at several stages of his youth, though Kundun covers a period three times longer. It is the final film penned by Mathison to be released before her death in 2015, although her final project, The BFG, was released posthumously.

Plot

[edit]

The film has a linear chronology with events spanning from 1937 to 1959;[3] the setting is Tibet, except for brief sequences in China and India. It begins with the search for the 14th mindstream emanation of the Dalai Lama. After a vision by Reting Rinpoche (the regent of Tibet) several lamas disguised as servants discover a promising candidate: a child born to a farming family in the province of Amdo, near the Chinese border.

These and other lamas administer a test to the child in which he must select from various objects the ones that belonged to the previous Dalai Lama. The child passes the test, and he and his family are brought to Potala Palace in Lhasa, where he will be installed as Dalai Lama when he comes of age.

During the journey, the child becomes homesick and frightened, but is comforted by Reting, who tells him the story of the first Dalai Lama–whom the lamas called "Kundun". As the film progresses, the boy matures in both age and learning. After a brief power struggle in which Reting is imprisoned and dies, the Dalai Lama begins taking a more active role in governance and religious leadership.

Meanwhile, the Chinese communists, recently victorious in their revolution, are proclaiming Tibet a traditional part of Imperial China and express their desire to reincorporate it with the newly formed People's Republic of China. Eventually, despite Tibet's pleas to the United Nations, the United States, the United Kingdom, and India for intervention, Chinese Communist forces invade Tibet. The Chinese are initially helpful, but when the Tibetans resist Communist reorganization and reeducation of their society, the Chinese become oppressive.

Following a series of atrocities suffered by his people, the Dalai Lama resolves to meet with Chairman Mao Zedong in Beijing. While Mao publicly expresses his sympathies to the Tibetan people and the Dalai Lama, and insists that changes must be made as the Dalai Lama sees fit, relations inevitably deteriorate. During their face-to-face meeting on the final day of the Dalai Lama's visit, Mao makes clear his view that "religion is poison" and that the Tibetans are "poisoned and inferior" because of it.

Upon his return to Tibet, the Dalai Lama learns of more horrors perpetrated against his people, who have by now repudiated their treaty with China and begun guerrilla action against the Chinese. After the Chinese make clear their intention to kill him, the Dalai Lama is convinced by his family and his Lord Chamberlain to flee to India.

After consulting the Nechung Oracle about the proper escape route, the Dalai Lama and his staff put on disguises and slip out of Lhasa under cover of darkness. During an arduous journey, throughout which they are pursued by the Chinese, the Dalai Lama becomes very ill and experiences two personal visions, first that their trip to India will be propitious and that, similarly, their eventual return to Tibet will also be propitious. The group eventually makes it to a small mountain pass on the Indian border. As the Dalai Lama walks to the guard post, an Indian guard approaches him, salutes, and inquires: "Are you the Lord Buddha?" The Dalai Lama replies with the film's final line: "I think that I am a reflection, like the moon on water. When you see me, and I try to be a good man, you see yourself." Once the Dalai Lama arrives at his new residence, he unpacks his telescope and steps outside. Erecting it and removing his spectacles, he gazes through it toward the Himalayas–and toward Tibet. The film concludes with two lines printed on screen: "The Dalai Lama has not yet returned to Tibet. He hopes one day to make the journey." The words shimmer into a dissolve upon the black screen as the credits begin.

Cast

[edit]

- Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong as the Dalai Lama (Adult)

- Gyurme Tethong as the Dalai Lama (Age 12)

- Tulku Jamyang Kunga Tenzin as the Dalai Lama (Age 5)

- Tenzin Yeshi Paichang as the Dalai Lama (Age 2)

- Tencho Gyalpo as Diki Tsering, the Dalai Lama's mother

- Tenzin Topjar as Lobsang (age 5 to 10)

- Tsewang Migyur Khangsar as the Dalai Lama's father

- Tenzin Lodoe as Takster Rinpoche, brother of the Dalai Lama

- Tsering Lhamo as Tsering Dolma

- Geshi Yeshi Gyatso as the Lama of Sera

- Losang Gyatso as The Messenger (as Lobsang Gyatso)

- Sonam Phuntsok as Jamphel Yeshe Gyaltsen, 5th Reting Rinpoche

- Gyatso Lukhang as Lord Chamberlain

- Lobsang Samten as Master of the Kitchen

- Jigme Tsarong as Taktra Rinpoche (as Tsewang Jigme Tsarong)

- Tenzin Trinley as Ling Rinpoche

- Robert Lin as Chairman Mao Zedong

- Jurme Wangda as Prime Minister Lukhangwa

- Jill Hsia as Little Girl

Production

[edit]The project began when screenwriter Melissa Mathison met with the Dalai Lama and asked him if she could write about his life. He gave her his blessing and his time, sitting for interviews that became the basis of her script. Mathison later suggested that Scorsese be brought in as director.[4] Scorsese first heard of Tibet when he watched Storm Over Tibet in the 1950s.[5] He met the Dalai Lama through Mathison and Harrison Ford.[6]

Universal Studios had a deal to produce Kundun, however, after the studio was purchased by Seagram, CEO Edgar Bronfman Jr. worried about the impact on the larger beverage business and declined to move forward with the film, resulting in it ending up at Disney.[7] Disney CEO Michael Eisner permitted the shooting of "Kundun" to proceed but, due to Chinese Communist Party pressure, he limited the film's distribution and marketing. "Kundun" was released on Christmas Day in 1997 in only two theaters nationwide.[citation needed]

Scorsese planned on shooting the film in Ladakh in India, but instead did it in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, near where The Last Temptation of Christ was filmed.[5] Most of the film was shot at the Atlas Film Studios in Ouarzazate, Morocco; some scenes were filmed at the Karma Triyana Dharmachakra monastery in Woodstock, New York.[8][9] Filming in Morocco meant that Scorsese had to wait eight days for the processed dailies to arrive and then Thelma Schoonmaker would have to wait an additional four days.[10]

Scorsese's previous film, Casino, only had two matte paintings while Kundun had forty.[11] The Dalai Lama was consulted for the film's set design.[12] Dancers from the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts were used for the film.[13]

Soundtrack

[edit]All tracks were composed by Philip Glass. Music was conducted by Michael Riesman. Music was produced by Kurt Munkacsi. The Executive Music Producer was Jim Keller.

Track listing

[edit]- "Sand Mandala" – 4:04

- "Northern Tibet" – 3:21

- "Dark Kitchen" – 1:32

- "Choosing" – 2:13

- "Reting's Eyes" – 2:18

- "Potala" – 1:29

- "Lord Chamberlain" – 2:43

- "Norbu Plays" – 2:12

- "Norbulingka" – 2:17

- "Chinese Invade" – 7:05

- "Fish" – 2:10

- "Distraught" – 2:59

- "Thirteenth Dalai Lama" – 3:23

- "Move to Dungkar" – 5:04

- "Projector" – 2:04

- "Lhasa at Night" – 1:58

- "Escape to India" – 10:05

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1998) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA Charts)[14] | 83 |

Release

[edit]Before the film was released, China's leaders hotly objected to Disney's plans to distribute the film, including to the point of threatening Disney's future access to China as a market.[15] Disney's steadfastness stood in stark contrast to Universal Pictures, which had earlier "turned down the chance to distribute Kundun for fear of upsetting the Chinese."[15] Scorsese, Mathison, and several other members of the production were banned by the Chinese government from ever entering China as a result of making the film.[16][17] China retaliated by banning Disney films and pulling Disney television cartoons.[18]

Disney apologized in 1998 for releasing the film and began to "undo the damage", eventually leading to a deal to open Shanghai Disneyland by 2016.[19] Former Disney CEO Michael Eisner has apologized for offending Chinese sensitivities, calling the film "a stupid mistake." He went on to say, "The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it. Here I want to apologize, and in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening."[20]

By 2015 Scorsese's ban had apparently been lifted as he attended the premiere of his short film The Audition in Macau.[21]

It was released on DVD and Blu-ray by Kino Lorber in 2019.[22]

Reception

[edit]The film was buried by Disney, which limited the release in order to minimize the damage to the company's relationship with the Chinese Communist Party,[23] resulting in less than $6 million in a limited U.S. distribution.[2] Kundun was nominated for four Academy Awards: for Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti, art direction and Francesca Lo Schiavo, set decoration), Best Cinematography (Roger Deakins), Best Costume Design, and Best Original Score (Philip Glass).

Critical reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 74% of 62 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.3/10. The website's consensus reads: "Hallucinatory but lacking in characterization, Kundun is a young Dalai Lama portrait presented as a feast of sight and sound."[24] Metacritic calculated an average score of 74 out of 100 based on 26 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[25]

There is rarely the sense that a living, breathing and (dare I say?) fallible human inhabits the body of the Dalai Lama. Unlike Scorsese's portrait of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ, this is not a man striving for perfection, but perfection in the shape of a man. ... Once we understand that Kundun will not be a drama involving a plausible human character, we are freed to see the film as it is: an act of devotion, an act even of spiritual desperation, flung into the eyes of 20th century materialism. The film's visuals and music are rich and inspiring, and like a mass by Bach or a Renaissance church painting, it exists as an aid to worship: It wants to enhance, not question.

Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four, saying it was "made of episodes, not a plot".[26] Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film "emotionally remote" while praising its look and its score: "The movie is a triumph for the cinematographer Roger Deakins, who has given it the look of an illuminated manuscript. As its imagery becomes more surreal and mystically abstract, Mr. Glass's ethereal electronic score, which suggests a Himalayan music of the spheres, gathers force and energy and the music and pictures achieve a sublime synergy."[3] Richard Corliss praised the cinematography and score as well: "Aided by Roger Deakins' pristine camera work and the euphoric drone of Philip Glass's score, Scorsese devises a poem of textures and silences. Visions, nightmares and history blend in a tapestry as subtle as the Tibetans' gorgeous mandalas of sand."[15] David Edelstein called the movie a hagiography whose "music ties together all the pretty pictures, gives the narrative some momentum, and helps to induce a kind of alert detachment, so that you're neither especially interested nor especially bored."[27] Mark Swed, writing in the Los Angeles Times, also lauded the musical score, opining that "it sounds neither like typical movie music, nor is it actual Tibetan music, however much Tibetan elements color and shape the score. It sounds, unmistakably, like Glass."[28]

Michael Wilmington of The Chicago Tribune gave the film four stars out of four, writing: "Hauntingly beautiful, raptly serious and vastly ambitious, Kundun is exactly the sort of movie that critics complain the major Hollywood studios never make -- and then tend to ignore or underrate when it finally appears."[29]

Barry Norman at the BBC opined that Kundun was "beautifully and intelligently made, far more impressive, for instance, than the recent Seven Years in Tibet".[30] As Kundun was released in the UK four months after its original release, Norman was able to probe Scorsese about the film's promotion. Writing about his interview with Scorsese, Norman said,

Yet it seems to be Scorsese, rather than the studio, who is doing most to promote the film. So I asked him "Did Disney back you up when it came out? Did they really put themselves behind it to try to sell it?" Now Scorsese is a decent and diplomatic man, who likes to be fair to everybody, but eventually he said: "I personally think that, unfortunately, they didn't push the picture." For fear of offending China? "Who knows?" he said. But, perhaps significantly, he also said: "The market China represents is enormous, not just for Disney but many other corporations around the world."[30]

Accolades

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]In 46 Long, the second episode of The Sopranos, Christopher Moltisanti, Adriana La Cerva, and friend Brendan Filone are waiting outside a nightclub when Scorsese (played by recording artist Tony Caso) is escorted inside by security. Christopher, excited to see the director, shouts "Marty! Kundun! I liked it."

The movie inspired the writing of the 2008 song "Chinese Democracy" off the album of the same name by hard rock band Guns N' Roses.[31]

In 2017, the web series Lasagna Cat featured the film's complete score in the hour-long episode "07/27/1978", in which John Blyth Barrymore delivers a philosophical monologue about a Garfield strip published on the titular date.[32]

See also

[edit]- Chinese censorship abroad

- List of Asian historical drama films

- List of TV and films critical of the Chinese Communist Party

- Seven Years in Tibet (film)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Kundun (1997)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c Kundun from The Numbers

- ^ a b December 24, 1997 Review from The New York Times

- ^ Overview of Kundun from the Turner Classic Movies website

- ^ a b Wilson 2011, p. 209.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 199.

- ^ Schwartzel, Erich (2022). Red carpet : Hollywood, China, and the global battle for cultural supremacy. New York. ISBN 978-1-9848-7899-1. OCLC 1250348753.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Karma Triyana Dharmachakra – The Monastery". Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- ^ "Young Spiritual Leader Arrives in New York Ready to Teach and Be Taught" from the New York Times May 16, 2008

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 220.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 221.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 212.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 216.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (PDF ed.). Mt Martha, Victoria, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 114.

- ^ a b c Disney's China Policy from Time magazine

- ^ "Change of direction for Scorsese". The National. December 7, 2011.

- ^ "37 Celebrities Banned From Foreign Countries". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Barboza, David; Barnes, Brooks (June 14, 2016). "How China Won the Keys to Disney's Magic Kingdom". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ Brzeski, Patrick (June 8, 2016). "Shanghai Disney Resort Finally Opens After 5 Years of Construction and $5.5B Spent". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ Rongji, Zhu (January 8, 2015). Zhu Rongji on the Record: The Road to Reform: 1998-2003. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815726296.

- ^ Miller, Julie (October 27, 2015). "Why Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert DeNiro, and Martin Scorsese Convened in a Macau Casino". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Barfield, Charles (August 1, 2019). "Martin Scorsese's Oscar-Nominated 'Kundun' Gets Special Edition Blu-Ray Later This Year". The Playlist.

- ^ "Hollywood relies on China to stay afloat. What does that mean for movies?". NPR. February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Kundun". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Kundun Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Review by Roger Ebert

- ^ Edelstein, David (December 26, 1997). "Holding Their Fire". Slate. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ^ Swed, Mark (January 9, 1998). "The Transcendent Sounds of 'Kundun'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (January 16, 1998). "HEAVEN SENT". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ^ a b "Martin Scorsese's KUNDUN conundrum". Radio Times. April 4–10, 1998.

- ^ Flumenbaum, David (February 24, 2009). "China Bans Democracy, Declares War on Guns N' Roses". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "Garfield, by smoking a pipe, has opened up a whole new world of dumb internet Garfield jokes". News. October 17, 2019. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

Works cited

[edit]- Wilson, Michael (2011). Scorsese On Scorsese. Cahiers du Cinéma. ISBN 9782866427023.

External links

[edit]- Kundun at IMDb

- Kundun at Box Office Mojo

- Kundun at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1997 films

- 1997 drama films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s Mandarin-language films

- American biographical drama films

- American epic films

- Cultural depictions of Mao Zedong

- Drama films based on actual events

- Film censorship in China

- Religious controversies in film

- Censored films

- Films about the 14th Dalai Lama

- Films directed by Martin Scorsese

- Films scored by Philip Glass

- Films set in India

- Films shot in Morocco

- Films shot in Ouarzazate

- Films with screenplays by Melissa Mathison

- Tibet–United States relations

- Tibetan-language films

- Chinese-language American films

- American multilingual films

- Touchstone Pictures films

- Films about Buddhism

- English-language biographical drama films