Koyaanisqatsi

| Koyaanisqatsi | |

|---|---|

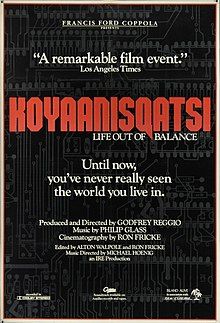

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Godfrey Reggio |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Godfrey Reggio |

| Cinematography | Ron Fricke |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Philip Glass |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates | |

Running time | 86 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Budget | $2.5 million[1][3] |

| Box office | $3.2 million[4] |

Koyaanisqatsi[b] is a 1982 American non-narrative documentary film directed and produced by Godfrey Reggio, featuring music composed by Philip Glass and cinematography by Ron Fricke. The film consists primarily of slow motion and time-lapse footage (some of it in reverse) of cities and many natural landscapes across the United States. The visual tone poem contains neither dialogue nor a vocalized narration: its tone is set by the juxtaposition of images and music. Reggio explained the lack of dialogue by stating "it's not for lack of love of the language that these films have no words. It's because, from my point of view, our language is in a state of vast humiliation. It no longer describes the world in which we live."[6] In the Hopi language, the word koyaanisqatsi means "life out of balance".[7]

It is the first film in The Qatsi Trilogy, which was followed by Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002).[8] The trilogy depicts different aspects of the relationship between humans, nature and technology. Koyaanisqatsi is the best known of the trilogy and is considered a cult film.[9][10] However, because of copyright issues, the film was out of print for most of the 1990s.[11] In 2000, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, aesthetically, or historically significant".[12][13]

Synopsis

[edit]Koyaanisqatsi runs for 86 minutes and comprises a montage of visuals accompanied by a minimal music score, without narration or dialogue. It opens with an ancient cave painting, followed by a close-up of a rocket launch, while a deep bass voice chants the film's title. The images dissolve into a sequence of landscapes with geological formations and dunes in the deserts of the American Southwest. Time-lapse imagery shows shadows quickly moving across landscapes, and the segment concludes with bats flying out of a cave.

Clouds move in time-lapse footage, which is followed by a waterfall, then ocean waves in slow-motion. This segues into footage of reservoirs, cultivated flowers, surface mining, electrical power infrastructure, evaporation ponds, oil drilling, blast furnaces, and concludes with a nuclear weapons test forming a mushroom cloud over the desert.

The following sequence begins with people sun bathing on a beach next to a power plant, followed by people touring a power plant. The next images show clouds reflected on the façade of a glass skyscraper, Boeing 747 aircraft taxiing at an airport, cars driving on urban freeways, military vehicles and aircraft, and explosive weapons dropping from the sky.

The film continues with images of skyscrapers in New York City, followed by areas of urban decay. Dilapidated buildings and other abandoned infrastructure are seen undergoing demolition and forming large dust clouds.

Clouds and sunlight are reflected in façades of glass skyscrapers in time-lapse, followed by people walking through busy city streets in slow-motion.

The next sequence begins with a sunset reflected in the façades of a glass skyscraper, before depicting people interacting with modern technology. Traffic, rush hours, technology-aided labors are depicted viscerally. The sequence begins to come full circle as the manufacture of cars in an assembly-line factory is shown. Daylight highway traffic is shown, followed by the movement of cars, shopping carts, televisions in an assembly line, and elevators. Time-lapses of various television shows being channel surfed are shown. In slow motion, several people react to being candidly filmed; the camera stays on them until the moment they look directly at it. Cars then move speedier.

Shots of microchips are interspersed with satellite photography of cities are shown, comparing the lay of each of them. Night shots of buildings are shown, as well as of people from all walks of life, from beggars to debutantes. A rocket in flight explodes, and the camera follows one of its engines as it falls back towards Earth. The film concludes with another image of the Great Gallery pictograph, this time with smaller figures.

The end title card lists translations of the Hopi word koyaanisqatsi:[1]

- "crazy life"

- "life in turmoil"

- "life out of balance"

- "life disintegrating"

- "a state of life that calls for another way of living"

The following screen shows a translation of the three Hopi prophecies sung in the final segment of the film:[1]

Over the end credits, the sound of human voices overlapping on television broadcasts can be heard.

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1972, Godfrey Reggio, of the Institute for Regional Education (IRE), was working on a media campaign in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which was sponsored by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The campaign involved invasions of privacy and the use of technology to control behavior. Instead of making public service announcements, which Reggio felt "had no visibility", advertising spots were purchased for television, radio, newspapers, and billboards.[15] Over thirty billboards were used for the campaign, and one design featured a close-up of the human eye, which Reggio described as a "horrifying image",[16] To produce the television commercials the IRE hired cinematographer Ron Fricke, who worked on the project for two years. The television advertisements aired during prime-time programming and became so popular that viewers would call the television stations to learn when the next advertisement would be aired.[15] Godfrey described the two-year campaign as "extraordinarily successful", and as a result, Ritalin (methylphenidate) was eliminated as a behavior-modifying drug in many New Mexico school districts.[16] But after the campaign ended, the ACLU eventually withdrew its sponsorship, and the IRE unsuccessfully attempted to raise millions of dollars at a fundraiser in Washington, D.C. The institute only had $40,000 left in its budget, and Reggio was unsure how to use the small amount of funds. Fricke insisted to Reggio that the money could be used to produce a film, which led to the production of Koyaanisqatsi.[17]

Filming

[edit]

Reggio and Fricke chose to shoot unscripted footage and edit it into an hour-long film.[17] Production began in 1975 in St. Louis, Missouri.[18] 16 mm film was used due to budget constraints, despite the preference to shoot with 35 mm film.[18][19] Footage of the Pruitt–Igoe housing project was shot from a helicopter, and Fricke nearly passed out during filming, having never flown in a helicopter before.[17] Reggio later chose to shoot in Los Angeles and New York City. As there was no formal script, Fricke shot whatever he felt would "look good on film".[20] While filming in New York City, Fricke developed an idea to shoot portraits of people. A grey paper backdrop was displayed in Times Square, and Fricke stood 10 feet (3 m) back with the camera. People walking by started posing for the camera, thinking it was a still camera, and several shots from the setup ended up in the film. Reggio was not on location in Times Square when Fricke shot the footage and thought the idea of shooting portraits of people was "foolish". Upon viewing the footage, Reggio decided to devote an entire section of the film to portraits. The footage was processed with a special chemical to enhance the film's shadows and details, as all footage was shot only with existing lighting. The IRE's $40,000 was exhausted after the filming, and almost two cases of film had been used. The unedited footage was screened in Santa Fe, New Mexico, but Fricke said it was "boring as hell" and there were "not that many good shots".[20] Fricke later moved to Los Angeles, and took a job as a waiter, unable to get a job in the film industry. While Fricke was working in Los Angeles, he edited the footage into a 20-minute reel, but "without regard for message or political content".[20]

I just shot anything that I thought would look good on film. Shooting bums, as well as buildings, didn't matter. It was all the same from my standpoint. I just shot the form of things.

The IRE was continuously receiving funding and wanted to continue the project in 1976, using 35 mm film.[20] After quitting his waiting job, Fricke traveled with a camera crew to the Four Corners, which was chosen for filming for its "alien look".[21] Due to the limited budget, Fricke shot with a 16 mm zoom lens onto 35 mm film. To compensate for the lens size, a 2× extender was added, which turned it into a full 35 mm zoom lens, allowing footage to be clearly captured onto 35 mm film. The two-week shoot included aerial footage taken from an airplane using a hand-held camera and ground footage taken using a tripod. The first aerial footage was too "shaky", so additional footage was taken from a camera mounted onto the airplane. Fricke traveled back to New York City in 1977, during which the New York City blackout occurred. Footage of the blackout was filmed in Harlem and the South Bronx, and the film was desaturated to match the appearance of the 16 mm footage.[21]

Reggio and Fricke came across time-lapse footage in "some low-visibility commercial work". They felt such footage was "the language [they] were missing", and collectively decided to implement time-lapse as a major part of the film to create "an experience of acceleration". For the time-lapse footage, Fricke purchased a Mitchell camera,[21] and built a motor with an intervalometer, which was used to precisely move the camera between frames. The system was powered by a gel cell battery that lasted for twelve hours, which enabled Fricke to shoot without the use of a generator.[22] Most time-lapse shots were filmed at a frame rate of 1½ frames per second. Fricke wanted the footage to "look normal" and not contain any "gimmicky" special effects.[22] The time-lapse shot overlooking the freeway in Los Angeles was filmed from the top of a building through a double exposure, with ten-second delay between frames. The first take was shot throughout the day for twelve hours, then the film was rewound and the same scene was shot at night for twenty minutes.[22] The scene with the Boeing 747 on the runway was filmed at Los Angeles International Airport, and was the longest continuous shot in the film. Fricke and his focus puller, Robert Hill, filmed at the airport every day for two weeks.[23] To keep the shot of the 747 within the frame, the camera was slowly moved by increasing the voltage to the gear motors.[22]

In addition to footage shot by Fricke, some of the footage of people and traffic in New York City was shot by cinematographer Hilary Harris. During post-production, Reggio was introduced to Harris' Organism (1975), which predominately features time-lapse footage of New York City streets. Reggio was impressed with Harris' work and subsequently hired him to work on Koyaanisqatsi.[24] Footage filmed by cinematographer Louis Schwartzberg was added into the cloud sequence, and additional stock footage was provided by MacGillivray Freeman Films.[25]

While Reggio was working on post-production at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio in 1981,[26] he met film director Francis Ford Coppola through an associate from Zoetrope Studios, Coppola's production company. Before shooting The Outsiders (1983) and Rumble Fish (1983), Coppola requested to see Koyaanisqatsi, and Reggio arranged a private screening shortly after its completion.[27] Coppola told Reggio that he was waiting for a film such as Koyaanisqatsi and that it was "important for people to see", so he added his name into the credits and helped present and distribute the film.[28] Coppola also decided to introduce and end the film with footage of pictographs from the Great Gallery at Horseshoe Canyon in Utah after visiting the site and becoming fascinated by the ancient sandstone murals.[29]

Music

[edit]| Koyaanisqatsi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album composed by | ||||

| Released | 1983 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack, film score, contemporary classical, minimalism | |||

| Length | 46:25 | |||

| Label | Antilles/Island | |||

| Producer | Kurt Munkacsi & Philip Glass | |||

| Philip Glass chronology | ||||

| ||||

The film's score was composed by Philip Glass and was performed by the Philip Glass Ensemble, conducted by Michael Riesman. One piece written for the film, "Façades", was intended to be played over a montage of scenes from New York's Wall Street. It ultimately was not used in the film; Glass released it as part of his album Glassworks in 1982.[30]

The opening for "The Grid" begins with slow sustained notes on brass instruments. The music builds in speed and dynamics throughout the piece's 21 minutes. When the piece is at its fastest, it is characterized by a synthesizer playing the piece's bass line ostinato.

Glass's music for the film is a highly recognizable example of the minimalist school of composition, which is characterized by heavily repeated figures, simple structures, and a tonal (although not in the traditional common practice sense of the word) harmonic language. Glass was one of the first composers to employ minimalism in film scoring, paving the way for many future composers of that style.[31] The choral pieces were sung for the film by the Western Wind Vocal Ensemble, a NYC-based 6-singer choral group specializing in choral and vocal music from many different eras and places, co-founded by William Zukof and Elliot Z. Levine.

An abbreviated version of the film's soundtrack was released in 1983 by Island Records. Despite the fact that the amount of music in the film was nearly as long as the film itself, this 1983 soundtrack release was only 46 minutes long, and only featured some of the film's pieces.

In 1998, Philip Glass re-recorded the film score for Nonesuch Records with a length of 73 minutes. This new recording includes new additional tracks that were cut from the film, as well as extended versions of tracks from the original album. This album was released as Koyaanisqatsi, rather than a soundtrack of the film.

In 2009, a remastered album was released under Philip Glass' own music label, Orange Mountain Music, as Koyaanisqatsi: Complete Original Soundtrack. This recording, with a length over 76 minutes, includes the original sound-effects and additional music that was used in the film.[32]

The music has become so popular that the Philip Glass Ensemble has toured the world, playing the music for Koyaanisqatsi live in front of the movie screen.

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Koyaanisqatsi" | 3:30 |

| 2. | "Vessels" | 8:03 |

| 3. | "Cloudscape" | 4:41 |

| 4. | "Pruit Igoe" | 7:02 |

| 5. | "The Grid" | 14:50 |

| 6. | "Prophecies" | 8:10 |

| Total length: | 46:16 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Koyaanisqatsi" | 3:28 |

| 2. | "Organic" | 7:43 |

| 3. | "Cloudscape" | 4:34 |

| 4. | "Resource" | 6:39 |

| 5. | "Vessels" | 8:05 |

| 6. | "Pruit Igoe" | 7:53 |

| 7. | "The Grid" | 21:23 |

| 8. | "Prophecies" | 13:36 |

| Total length: | 73:21 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Koyaanisqatsi" | 3:27 |

| 2. | "Organic" | 4:57 |

| 3. | "Clouds" | 4:38 |

| 4. | "Resource" | 6:36 |

| 5. | "Vessels" | 8:13 |

| 6. | "Pruitt Igoe" | 7:51 |

| 7. | "Pruitt Igoe Coda" | 1:17 |

| 8. | "SloMo People" | 3:20 |

| 9. | "The Grid Introduction" | 3:24 |

| 10. | "The Grid" | 18:06 |

| 11. | "Microchip" | 1:47 |

| 12. | "Prophecies" | 10:34 |

| 13. | "Translations and Credits" | 2:11 |

| Total length: | 76:21 | |

Meaning

[edit]

Reggio stated that the Qatsi films are intended to simply create an experience and that "it is up [to] the viewer to take for himself/herself what it is that [the film] means." He also said that "these films have never been about the effect of technology, of industry on people. It's been that everyone: politics, education, things of the financial structure, the nation state structure, language, the culture, religion, all of that exists within the host of technology. So it's not the effect of, it's that everything exists within [technology]. It's not that we use technology, we live technology. Technology has become as ubiquitous as the air we breathe ..."[6]

In the Hopi language, the word koyaanisqatsi literally translates to "chaotic life".[34] It is a compound word composed of the bound form koyaanis- ("corrupted" or "chaotic")[34] and the word qatsi ("life" or "existence").[35] The Hopi Dictionary defines koyaanisqatsi as "life of moral corruption and turmoil" or "life out of balance", referring to the life of a group.[34] The latter translation has been used in promotional materials for the film and is one of the five definitions listed before the closing credits.[1]

In the score by Philip Glass, the word "koyaanisqatsi" is chanted at the beginning and end of the film in an "otherworldly"[36] dark, sepulchral basso profondo by singer Albert de Ruiter over a solemn, four-bar organ-passacaglia bassline. Three Hopi prophecies sung by a choral ensemble during the latter part of the "Prophecies" movement are translated just prior to the end credits.

During the end titles, the film gives Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich, David Monongye, Guy Debord, and Leopold Kohr credit for inspiration. Moreover, amongst the consultants to the director are listed names including Jeffrey Lew, T. A. Price, Belle Carpenter, Cybelle Carpenter, Langdon Winner, and Barbara Pecarich.

Releases

[edit]Theatrical distribution

[edit]Koyaanisqatsi was first publicly screened as a workprint at the Santa Fe Film Festival on April 27, 1982.[37] Later that year, the film premiered at the Telluride Film Festival on September 5.[1] It was screened again at the New York Film Festival (NYFF) on October 4, which was promoted as the film's "world premiere", despite its previous screening in September.[38] While the NYFF was based in the Lincoln Center, an exception was made to screen Koyaanisqatsi at the larger Radio City Music Hall due to the film's "spectacular visual and sound quality".[39]

Triumph Films offered to distribute the film, but Reggio turned down the offer as he wanted to work with a smaller company so he could be more involved with the release. He chose Island Alive as the distributor, a company newly formed in 1983 by Chris Blackwell of Island Records,[40] and Koyaanisqatsi was the company's first release. Select theaters distributed a pamphlet that defined the title and the Hopi prophecies sung in the film, as well as a copy of the soundtrack from Island Records. The first theatrical run featured four-track Dolby Stereo sound, while later runs featured monaural sound.

The film's initial limited release began in San Francisco at the Castro Theatre on April 27, 1983.[41] The producers spent $6,500 on marketing the initial release, which grossed $46,000 throughout its one-week run, and was the highest-grossing film in the San Francisco Bay Area that week. It was released in Los Angeles a month later where it grossed $300,000 at two theaters within 15 weeks. Additional releases in select cities throughout the United States continued in September 1983, beginning with a release in New York City on September 15. In mid-October, Koyaanisqatsi was released onto 40 to 50 screens throughout the country.[42] It was a surprise arthouse hit as well as a popular presentation at colleges and universities.[43][44][45]

It ultimately grossed $3.2 million at the box office, and became the second-highest-grossing documentary of the 1980s, following Roger & Me (1989).[4]

Home media

[edit]Koyaanisqatsi was originally released on VHS and laserdisc by Michael Nesmith's Pacific Arts Video.[46][47]

The rights to Koyaanisqatsi were passed through various multinational entertainment companies, which eventually prevented a home video release. IRE enforced their legal and contractual rights by creating a federal court lawsuit. IRE distributed a privately issued release of the film on DVD. The release was available to those who made a donation of at least $180 to IRE, and was distributed in a sleeve that was signed by Reggio.[48]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) eventually received the rights to the film, and Koyaanisqatsi was released on DVD by MGM Home Entertainment on September 18, 2002, coinciding with the release of Naqoyqatsi (2002). Both films were available in a two-disc box set. Each DVD includes a documentary with interviews by Reggio and Glass and trailers for the Qatsi trilogy.[49] Unlike the IRE release, which featured the film in the open matte format in which it was filmed, the MGM release was cropped into a widescreen aspect as it originally was presented in theaters.[50]

On January 13, 2012, a Blu-ray version (screen ratio 16:9) was released in Germany.[51] The Blu-ray was also released in Australia by Umbrella Entertainment on March 22, 2012.[52] In December 2012, Criterion released a remastered DVD and Blu-ray of Koyaanisqatsi, as part of a box set containing the Qatsi Trilogy. The release features 5.1 surround sound audio and a restored digital transfer of the film in 1.85:1 aspect ratio, approved by director Godfrey Reggio.[53]

Reception

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, Koyaanisqatsi has an approval rating of 91% based on 22 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10. The website's critical consensus reads "Koyaanisqatsi combines striking visuals and a brilliant score to produce a viewing experience that manages to be formally daring as well as purely entertaining."[54] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 72 out of 100, based on 10 critics, indicating "generally favourable reviews".[55] In 1983, the film was entered into the 33rd Berlin International Film Festival.[56] Czech pedagogue Rudolf Adler, in his textbook for film educators, describes Koyaanisqatsi as "formulated with absolute precision and congenial expression."[57]: 60 It has also been described as a postmodernist film.[58]

Koyaanisqatsi is followed by the sequels Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi and the shorts Anima Mundi and Evidence. Naqoyqatsi was completed after a lengthy delay caused by funding problems and premiered in the United States on October 18, 2002. The film's cinematographer Ron Fricke went on to direct Baraka, a pure cinema movie that is often compared to Koyaanisqatsi.

Legacy

[edit]- The theme song of the Commodore 64 game Delta is based on the film's theme score.

- A clip of this film was featured in the 2016 film 20th Century Women.[59][60][61]

- The trailer for Grand Theft Auto IV resembles the style of the film, featuring different shots of the fictional Liberty City, with the track "Pruit Igoe" in the background. This track also appears in the final cutscene of the missions "Out of Commission" and "A Revenger's Tragedy" alongside the in-game radio station The Journey.[62]

- The 2009 film Watchmen accompanies the origin story of its character Doctor Manhattan with a montage of the pieces "Prophecies" and "Pruit Igoe", and features the same tracks in its trailer.[63]

- The film inspired the album Music to Films by Dr. Atmo and Oliver Lieb, released on the record label FAX +49-69/450464. The music is completely synchronized to the film.

- The noise rock band Cows covered a version of the title track, "Koyaanisqatsi", on their 1987 debut album, Taint Pluribus Taint Unum.

- The chanted "koyaanisqatsi" lyric from the film's title song was parodied in P. D. Q. Bach's "Prelude to Einstein on the Fritz" (itself a pun on the title of the opera Einstein on the Beach composed by Philip Glass), replaced with the lyric "coy hotsy-totsy".[64]

- This film also inspired RaMell Ross's 2018 Oscar-nominated documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening.[65][66]

- Koyaaniqatsi was cited as an inspiration for the viral Simcity 3000 video Magnasanti.[67][68][69]

- A 1999 episode of The Simpsons, "Hello Gutter, Hello Fadder", opens with a 26-hour time lapse of Homer's bedroom while he oversleeps.

- The Arkansas Governor's School, a month long public residential academic program offered by the Clinton Foundation to rising seniors in the state of Arkansas, screens Koyaanisqatsi to every incoming class to prompt discussion regarding philosophy, political science, and English.

- A 2010 episode of The Simpsons, "Stealing First Base", features a parody Itchy & Scratchy film titled Koyaanis-Scratchy: Death Out of Balance.[70]

- Two Scrubs episodes feature the main title music with intense staring (the janitor giving JD the 'evil eye'): Season 5, episode 5 My New God[71] and episode 17 My Chopped Liver.[72]

- The music video for Madonna's song "Ray of Light" was heavily inspired by the "Grid" sequence from the movie.[73]

- A 2005 episode of Gilmore Girls features the title music during a scene featuring a character performing an interpretive dance.[74]

- The fourth season of the Netflix original series Stranger Things features the track "Prophecies" in its seventh episode.[75][76]

- Koyaanisqatsi was performed live at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, on July 23, 2009.[77]

- Koyaanisqatsi was again performed live, in Montreal at the Place des Arts, on September 14, 2019.[78]

- Dutch-Korean harpist Lavinia Meijer included excerpts from the film's score on her 2017 album The Glass Effect.[79]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Reggio is credited for "Concept"; all four writers are credited for "Scenario"[1]

- ^ Pronounced /koʊˈjɑːnisˈkɑːtsi/ koh-YAH-nees-KAHT-see; Hopi: [koˈjaːnisˈqat͡si][5]

- ^ Hopi: Yaw itam it awk haykyanayawk yaw oova iwiskövi.[14]

- ^ Hopi: Naanahoy lanatini naap yaw itamit hiita kya-hak hiita töt sqwat angw ipwaye yaw itam hiita qa löl mat awkökin.[14]

- ^ Hopi: Yaw yannak yangw sen kisats köö tsaptangat yaw töövayani oongawk.[14]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Koyaanisqatsi (1983)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi (U)". British Board of Film Classification. 1983. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-8357-1776-2.

- ^ a b Plantinga, Carl (May 16, 2006). "The 1980s and American Documentary". In Williams, Linda Ruth; Hammond, Michael (eds.). Contemporary American Cinema. McGraw Hill Education. p. 291. ISBN 0-3352-2843-7. Retrieved February 24, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hopi Dictionary Project 1998, pp. 863–864.

- ^ a b Carson, Greg (director) (2002). Essence of Life (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ "Film: Koyaanisqatsi". Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "TCM.com".

- ^ "Cult Koyaanisqatsi blends music, film". The Michigan Daily. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Cult Movies on Videocassette, 1987 - Siskel and Ebert Movie Reviews

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi". Spirit of Baraka. May 21, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "Welcome to Koyaanisqatsi". www.koyaanisqatsi.org. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Brief Descriptions and Expanded Essays of National Film Registry Titles|Library of Congress

- ^ a b c "Philip Glass: Prophecies lyrics". Musicmatch. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1992, p. 383.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1992, p. 384.

- ^ a b c Gold 1984, p. 63.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1992, p. 385.

- ^ MacDonald 1992, p. 386.

- ^ a b c d e Gold 1984, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Gold 1984, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Gold 1984, p. 68.

- ^ Gold 1984, p. 70.

- ^ MacDonald 1992, p. 387.

- ^ Gold 1984, p. 72.

- ^ Torneo, Erin (October 18, 2002). "INTERVIEW: Lone Giant: Godfrey Reggio's 'Naqoyqatsi'". IndieWire. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ MacDonald 1992, p. 399.

- ^ Ramsey 1986, p. 62.

- ^ Hillinger, Charles (August 10, 1986). "The Past Comes to Life in Horseshoe Canyon". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ "Facades – Philip Glass". Philip Glass.

- ^ Eaton, Rebecca Marie Doran (May 2008). Unheard Minimalisms: The Functions of the Minimalist Technique in Film Scores (PDF). Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ "Complete Original Soundtrack (Orange Mountain Music) OMM 0058". Archived from the original on June 8, 2009.

- ^ Koyaanisqatsi (Original Motion Picture Score). AllMusic.com. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Hopi Dictionary Project 1998, p. 154.

- ^ Hopi Dictionary Project 1998, p. 463.

- ^ Neveldine, Robert Burns (1998). Bodies at Risk: Unsafe Limits in Romanticism and Postmodernism. SUNY Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780791436493.

- ^ "New Mexico Filmmakers Play a Part in "Samsara"". Santa Fe Film Festival. November 2, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (October 6, 1982). "Koyaanisqatsi". Variety. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Insdorf, Annette (September 19, 1982). "The Film Festival Turns 20, Mixing Old and New". The New York Times. ProQuest 424423676. Retrieved March 12, 2024 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Our Founder: Chris Blackwell". Island Outpost. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ "Theatrical Release Dates – April 1983". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ Kreps, Karen (December 1983). "The Marketing of Koyaanisqatsi". Boxoffice. p. 68. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Godfrey Reggio/IRE Collection - Harvard Film Archive

- ^ Godfrey Reggio, Cinematic Seer - Harvard Film Archive

- ^ Synaesthetic Cinema: Minimalist Music and Film - Harvard Film Archive

- ^ LaserDisc Database

- ^ At the Cassette Store, 1985 (incomplete) - Siskel and Ebert Movie Reviews

- ^ "How You Can Help: Getting Involved". Koyaanisqatsi.org. IRE. Archived from the original on November 9, 2000. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn. "Koyaanisqatsi & Powaqqatsi". DVD Savant. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi DVD Comparison". DVD Beaver. Comparison between the two versions. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "German Blu-ray release". Amazon.de. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "Australian Blu-ray release". Umbrellaent.com.au. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi (1983) | The Criterion Collection". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi – Life Out of Balance (1982)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Koyaanisqatsi". Metacritic.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1983 Programme". berlinale.de. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ Adler, R., Audiovizuální a Filmová výchova ve vyučování (Prague: Gymnázium a Hudební škola hlavního města Prahy, 2018), p. 60.

- ^ The Postmodern Presence - Google Books (pg.37)

- ^ Newman, Nick (October 7, 2016). "[NYFF Review] 20th Century Women".

- ^ "Twentieth Century Women (2016)". March 31, 2017.

- ^ "Review: Mike Mills' '20th Century Women'". MUBI. December 27, 2016.

- ^ "Pruitt Igoe". Philip Glass.

- ^ "What Songs Appear on the 'Watchmen' Movie Soundtrack?". About.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Gann, Kyle (January 19, 1999). "Classical Trash". The Village Voice. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "How The Qatsi Trilogy Gave RaMell Ross a New Way of Seeing". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "Under the Influence: RaMell Ross on THE QATSI TRILOGY". February 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Magnasanti.

- ^ "Magnasanti (Vincent Ocasla)". January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Q+A: Vincent Ocasla, the 22-Year-Old Who Designed the Perfect Totalitarian City". April 30, 2011.

- ^ Short, Hogan (April 17, 2017). "11 Films You Didn't Know Were Perfect to Watch on 4/20". BeatRoute Magazine. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ ""Scrubs" My New God (TV Episode 2006)". IMDb.

- ^ ""Scrubs" My Chopped Liver (TV Episode 2006) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "My favourite film: Koyaanisqatsi". the Guardian. December 15, 2011.

- ^ "Top 10 musical memories on 'Gilmore Girls,' before its much-anticipated reboot". Dallas News. November 22, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Bitran, Tara (May 27, 2022). "Every Song in Volume 1 of 'Stranger Things' Season 4". Netflix. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Bundel, Ani (May 28, 2022). "The Stranger Things 4 Soundtrack Brings All the '80s Nostalgia". Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "Philip Glass Ensemble, LA Philharmonic Perform to "Koyaanisqatsi" at Hollywood Bowl | Nonesuch Records". July 23, 2009.

- ^ "Philip Glass | KOYAANISQATSI LIVE – Life out of Balance | TRAQUEN'ART".

- ^ "Recording reviews: a Glass harpist, arias for Farinelli". The Washington Post

Bibliography

[edit]- Gold, Ron (March 1984). "Untold Tales of Koyaanisqatsi". American Cinematographer. 65 (3): 62–74.

- Hopi Dictionary Project (1998). Hopi Dictionary [Hopìikwa Lavàytutuveni]. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1789-4. Retrieved March 10, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, Scott (1992). "Godfrey Reggio". A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 378–401. ISBN 0-520-07917-5.

- Ramsey, Cynthia (1986). "Koyaanisqatsi: Godfrey Reggio's filmic definition of the Hopi concept for 'life out of balance'". In Douglas Fowler (ed.). The Kingdom of Dreams: Selected Papers from the Tenth Annual Florida State University Conference on Literature and Film. Tallahassee: Florida State University Press. pp. 62–78. ISBN 0-8130-0863-8.

- Streible, Dan (2006). "Koyaanisqatsi". In Ian Aitken (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge. pp. 738–739. ISBN 0-415-97638-3.

External links

[edit]- Koyaanisqatsi at the Godfrey Reggio Foundation

- Koyaanisqatsi at IMDb

- Koyaanisqatsi at the TCM Movie Database

- Koyaanisqatsi at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1982 films

- 1980s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1982 documentary films

- American avant-garde and experimental films

- American independent films

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about environmental issues

- Documentary films about technology

- Existentialist films

- Films scored by Philip Glass

- Films directed by Godfrey Reggio

- Films without speech

- United States National Film Registry films

- Non-narrative films

- Films shot in Utah

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in Chicago

- Films shot in Missouri

- Films shot in St. Louis

- 1980s American films

- Postmodern films

- 1982 directorial debut films

- Qatsi trilogy