Khurnak Fort

| Khurnak Fort | |

|---|---|

| Native name མཁར་ནག (Standard Tibetan) | |

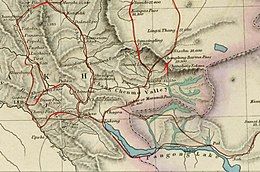

1988 CIA map showing Khurnak Fort in Aksai Chin | |

| Coordinates | 33°45′25″N 78°59′50″E / 33.75694°N 78.99722°E |

| Elevation | 4,257 meters |

| Khurnak Fort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 庫爾納克堡 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 库尔纳克堡 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 庫爾那克堡 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 库尔那克堡 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Khurnak Fort (Tibetan: མཁར་ནག, Wylie: mkhar nag, THL: khar nak)[1] is a ruined fort on the northern shore of Pangong Lake, which spans eastern Ladakh in India and Rutog County in the Tibet region of China. The area of the Khurnak Fort is disputed by India and China, and has been under Chinese administration since 1958.

Though the ruined fort itself is not of much significance, it serves as a landmark denoting the middle of Pangong Lake. The fort lies at the western edge of a large plain formed as the alluvial fan of a river called Changlung Lungpa, which falls into Pangong Lake from the north. The plain itself is called Ote Plain locally, but is now generally called the Khurnak Plain.[2][3]

Geography

[edit]

The Khurnak Fort stands on a large plain called Ot or Ote at the centre of Pangong Lake on its northern bank. In recent times, the plain has come to be called the "Khurnak Plain", after the fort. The plain divides Pangong Lake into two halves: to the west is the Pangong Tso proper and to the east are a string of lakes called Nyak Tso, Tso Ngombo, or other names.[5][6][c]

The Khurnak Plain is 8 miles long and 3 miles wide. It is, in fact, the mouth of a valley called "Changlung Lungpa" ( also called "Chang Parma", meaning "northern middle"). The river that flows through the valley[d]—about 40 to 50 miles long—brings down waters from numerous glaciers lying between Pangong Lake and the Chang Chenmo Valley. The plain is formed by the alluvial deposits of the river encroaching into the bed of the lake.[3][10] The growth of the plain over the millennia has reduced the lake in its vicinity to a narrow channel "like a large river" for about 2–3 miles, with a minimum breadth of 50 yards. The constrained flow of water from east to west makes the lower lake to the west (Pangong Tso) considerably more saline than the eastern lake (Tso Ngombo).[3][11]

The top of the Changlung Lungpa valley is marked by a grazing ground called Dambu Guru. Here, the valley branches into two valleys, one going northwest to the Marsimik La pass and the other going northeast to the pastures of Nyagzu and Migpal. Migpal is connected via mountain passes to both the Chang Chenmo Valley in the northwest and the well-watered village of Noh in the southeast.

H. H. Godwin-Austen[e] noted in 1867 that all of Khurnak Plain had considerable growth of grass and formed a winter grazing area for the Changpa nomads. The snow never stayed for long on the Khurnak Plain, even when the lake itself froze. The Changpa nomads of Noh (also called Üchang or Wujiang)[12] and Rudok camped out at the plain during the winter. To protect the tents against the wind, walls of stone and earth were built, and the floors were dug 3 feet deep.[13] Strachey also labelled the Khurnak Plain as "Uchang Tobo", which might indicate a connection with the village of Noh.

Access

[edit]The Khurnak Plain is accessible from both Ladakh and Rudok via multiple routes. Strachey noted two access routes from Ladakh, one via Kiu La and the other via the Chang Chenmo valley and Kyungang La. These were usable in the summer. A third route from the south, crossing the narrow channel of the lake, shown in later maps as a ford, would have been the easiest route to the Khurnak Plain (Map 3). The ability to ford the lake here was found erroneous in later British testimonies.[14]

From the Tibetan side, a route along the northern shore of Pangong Lake was available. Sven Hedin witnessed it being used as a trade route by Ladakhi traders going to Rudok.[15] The route was difficult to traverse in parts because of cliffs jutting into the lake. However, this was no impediment in winter when the lake froze.[16] In addition, a longer route from Noh via Migpal was also available.[17] (Map 3)

Khurnak Fort

[edit]Godwin-Austen mentioned the Khurnak Fort, whose ruins stood on a low rock (elevation: 4,257 m) on the northwestern side of the plain. Judging from its site, he believed that it belonged to Tibetans who presumably built it "years ago". But its proximity to Leh and the strength of its Thanadar (governor), he thought, placed it in Kashmiri territory. The Khurnak Plain was a "disputed ground", according to Godwin-Austen, which was claimed by the Ladakhis as well as the Tibetans of Rudok.[18][19]

Evidently, the purpose of the fort was to guard against Ladakhis crossing to the Khurnak Plain from the south, crossing the narrow channel of the lake. Such activity was witnessed during the times of the British Raj as well.[20] The Khurnak Plain, being a prized winter pasture ground, was the preserve of the shepherds from Noh, the only permanently inhabited place on the north shore of Pangong Lake. Ladakhis, who lived south of Pangong Lake, had their winter pastures in Skakjung, much further to the south.[21]

History

[edit]

In 1863, British topographer Henry Haversham Godwin-Austen described Khurnak as a disputed plain claimed both by inhabitants of Panggong district and Tibetan authorities from Lhasa. He personally believed that it should belong to the latter due to the "old fort standing on a low rock on the north-western side of the plain" previously built by the Tibetans.[22][13] Godwin-Austen remarked that the Kashmiri authorities in Leh had recently exerted their influence in the region such that Khurnak was effectively controlled by the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.[19][13]

According to Alastair Lamb, the majority of British maps published between 1918 and 1947 showed Khurnak as being in Tibet.[23]

Sino-Indian border dispute

[edit]Prior to 1958, the boundary between India and China was considered to be at the Khurnak Fort[24][25] and Indian forces visited it from time to time and had a post there.[24] China wrested its control since around July 1958, according to most sources.[24][26]

During the 1960 talks between the two governments on the boundary issue, India submitted official records, including the 1908 Settlement Report, which recorded the amount of revenue collected at Khurnak, as proof of jurisdiction over Khurnak.[27] The Chinese claim line of 1956 did not include the Khurnak Fort, but the 1960 claim line included the Khurnak Fort.[28]

In 1963, Khurnak Fort was described by the US National Photographic Interpretation Center as follows:

Location--33-44N 78-59E, 20 nm north-east of Chushul, on the north shore of PangongTso. Facilities--one large barracks-type building, 2 large storage-type buildings, and 9 smaller buildings; dry moat on three sides; six AW positions and several individual firing positions. Served by natural surface road; no vehicles observed.[29]

As of 2019, a PLA border patrol company of the Western Theater Command was stationed nearby.[30]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Henry Strachey was an officer of the British Indian Army, who was noted for his independent exploration effort. In 1947, he was included as a commissioner in a Kashmir Boundary Commission headed by Alexander Cunningham.

- ^ Henry Strachey explored the frontier of Ladakh as part of the British boundary commission for the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in 1847. The extensive local knowledge gathered by him is published in Physical Geography of Western Tibet in 1951. His boundary commissioner's report is only available in Government archives.[4]

- ^ Godwin-Austen says that the eastern lake is divided into fourth sections called Nyak Tso, Rum Tso and Tso Nyak.[7] Hedin says that he never heard those names from the local people and its real name is Tso Ngombo.[8]

- ^ The stream flowing from here is unlabelled in British maps, but it is occasionally referred to as the Nyagzu stream. Hedin has noted the similarity of "Nyagzu" to "Nyak Tso" (the "middle lake"). A better parsing of Nygazu might be "Nyak Chu", which would mean the middle stream or middle river.[9]

- ^ H. H. Godwin-Austen was a surveyor with the Great Trigonometric Survey, who was part of the Kashmir Survey team, 1855–1865. He did plane-tabling in this part of Ladakh. He also explored the Karakoram Range and named its peaks.

- ^ From map: "THE DELINEATION OF INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES ON THIS MAP MUST NOT BE CONSIDERED AUTHORITATIVE"

References

[edit]- ^ Ngari Prefecture, KNAB Place Name Database, retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), pp. 351–352.

- ^ a b c Strachey, Physical Geography of Western Tibet (1854), p. 46.

- ^ Kaul, India China Boundary in Kashmir (2003), pp. 60–62.

- ^ Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 638.

- ^ Strachey, Physical Geography of Western Tibet (1854), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), p. 353.

- ^ Hedin, Central Asia, Vol. IV (1907), p. 264.

- ^ Hedin, Central Asia, Vol. IV (1907), p. 312: "On the map in question the river bears no name. It is there that the big, broad glen of Niagzu debouches, and in its outlet, on the right side, the map places the ruins of the fort of Khurnak; near these on the occasion of my visit stood a couple of Tibetan tents. I never heard the name Nyak-tso, which the map applies to the whole of the freshwater lake; the only name I heard was Tso-ngombo, or the Blue Lake. Everybody on the other hand knew the name: Niagzu, and possibly Nyak-tso has been confounded with that name."

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), p. 352: "The silt, which in former times has been carried down from the above area, has formed the plain of Ote, the broad barrier to what would otherwise be a continuous long reach of water."

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), pp. 351–352: "The waters of the western end are far more salt than those of that near Ote, noticeable even to the taste, but it is not until the stream that connects the two portions is fairly entered that it is by any means drinkable; thence for the whole distance eastward we used to take water..."

- ^ Howard, Neil; Howard, Kath (2014), "Historic Ruins in the Gya Valley, Eastern Ladakh, and a Consideration of Their Relationship to the History of Ladakh and Maryul", in Erberto Lo Bue; John Bray (eds.), Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, p. 97, ISBN 9789004271807: "[Discussing the meaning of dBus byang] One [possibility] is the existence (in modern times at least) of a place called Üchang (dBus byang, Chinese Wujiang) at the eastern end of the Panggong Tsho, missed by Vitali.

- ^ a b c Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), p. 355.

- ^ Ward, Tourist's and Sportsman's guide (1896), Route No. 9 (pp. 108–109): "It is a mistake, as noted in the Atlas sheets, to call the Khurnak crossing a ford; the water is generally from 7 to 10 feet deep, and a raft has to be constructed."

- ^ Hedin, Central Asia, Vol. IV (1907), pp. 281–283: "Occasionally we would meet on the northern track a caravan of sheep, laden with corn put up in small sacks, and travelling from Leh or Tanksi. One that we met this day consisted of 200 sheep: it was quite a pleasure to see how well-trained the animals were, and how orderly they marched along without being especially looked after."

- ^ Hedin, Sven (March 1903), "Three Year Exploration in Central Asia, 1899–1902", The Geographical Journal, XXI (3): 256: "In one place the cliffs plunged down into the water so precipitously that it looked for a time as if we should be unable to proceed further. ... We had but to wait two or three days for the ice to thicken, and then we drew the baggage past the place of danger on an improvised sledge."

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), pp. 360–361: "To the south [of the Kiepsang peak, reachable from Noh and Pal] the great tributary of the Pangong, the Mipal Valley, could be followed for many miles..."

- ^ Godwin-Austen, Notes on the Pangong Lake District (1867), p. 355: "The said plain is a disputed piece of ground, the men of the Pangong district claim it; though, judging by the site of an old fort standing on a low rock on the north-western side of the plain, I should say it undoubtedly belongs to the [Lhassan] authorities, by whom it was built years ago; proximity of Leh and greater part of the Thanadar there, places it in the Kashmir Rajah's territory."

- ^ a b Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 72.

- ^ Ward, Tourist's and Sportsman's guide (1896), pp. 8, 108: "In some years the guards at Khurnak do not appear; in others they come down in force, then they are simply masters of the situation as they can prevent the rafts landing."

- ^ P. Stobdan, Shift in India's Border Defence Provokes China, Maagzter, June 2020. "The area is locally known as Skakjung located 300 kilometres east of Leh and is traditionally the only winter pasture for several villages including Chushul, Tsaga, Niddar, Nyoma, Mud, Dungti, Kuyul, Loma etc. This area is located on the [left] bank of Indus between Dungti and Fuktse but the area extends even up to Demchok."

- ^ Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 72: "the said plain ... [of Khurnak] ... is a disputed piece of ground, the men of the Panggong district claim it; though, judging by the site of an old fort standing on a low rock on the north-western side of the plain, I should say that it undoubtedly belongs to the Lhassan authorities, by whom it was built years ago."

- ^ Lamb, Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector (1965), p. 39.

- ^ a b c Pg. 74, La Question de la frontière Sino-Indienne, 1967

- ^ Negi, S.S. (2002). Cold Deserts of India (Second ed.). Indus Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9788173871276.

- ^

See:

- Gonon, Emmanuel (2011). Marches et frontières dans les Himalayas. Presses Universite Du Quebec. p. 206. ISBN 978-2760527034.

- N. Jayapalan (2001). Foreign Policy of India. p. 206. ISBN 9788171568987.

- K. V. Krishna Rao (1991). Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security. p. 75. ISBN 9788172120016.

- M. L. Sali (1998). India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector. p. 82. ISBN 9788170249641.

- Praveen Swami. "China's Ladakh intrusion: Two maps tell this dangerous story". Firstpost. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Appadorai, Angadipuram; Rajan, Mannaraswamighala Sreeranga (1985), India's Foreign Policy and Relations, South Asian Publishers, p. 120, ISBN 978-81-7003-054-6

- ^ Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963). Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh. Praeger. p. 111 – via archive.org.

- ^ Patterson, George N. (Oct–Dec 1962). "Recent Chinese Policies in Tibet and towards the Himalayan Border States". The China Quarterly (12): 195. JSTOR 651824.

- ^ "SINO-INDIAN BORDER DEFENSE CHUSHUL AREA" (PDF). National Photographic Interpretation Center. February 1963. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017 – via CIA. Alt URL

- ^

China Youth Daily (2019-02-11). "零下20摄氏度!边防官兵巡逻在海拔5700米的雪域高原上" (in Chinese). Sina Corp.

驻守在班公湖畔的新疆军区某边防团库尔那克堡边防连巡逻分队

Bibliography

[edit]- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890 – via archive.org

- Godwin-Austen, H. H. (1867). "Notes on the Pangong Lake District of Ladakh, from a Journal Made during a Survey in 1863". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 37: 343–363. doi:10.2307/1798534. JSTOR 1798534.

- Hedin, Sven (1907), Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia, 1899–1902, Vol. IV: Central and West Tibet, Stockholm: Lithographic Institute of the General Staff of the Swedish Army – via archive.org

- Kaul, Hriday Nath (2003). India China Boundary in Kashmir. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-212-0826-0.

- Lamb, Alastair (1965). "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF). The Australian Year Book of International Law. 1 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1163/26660229-001-01-900000005.

- Strachey, Henry (1854), Physical Geography of Western Tibet, London: William Clows and Sons – via archive.org

- Ward, A. E. (1896), The Tourist's and Sportsman's guide to Kashmir and Ladak, Thaker, Spink & Co – via archive.org

External links

[edit]- "Khurnak Fort". getamap.net. Retrieved 29 August 2013.