Nyckelharpa

Nyckelharpa being played | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | key harp Danish: nøgleharpe ("key harp") Finnish: avainviulu ("key violin") German: Schlüsselfidel ("key vielle") Italian: viola a chiavi ("keyed viola") Spanish: viola de teclas ("keyed violin") |

| Classification | Bowed string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322–71 |

| Inventor(s) | Folk instrument |

| Developed | 12th century |

| Related instruments | |

| Hurdy-gurdy | |

Nyckelharpa network, an innovative dissemination of a music and instrument-building tradition with roots in Sweden | |

|---|---|

| Country | Sweden |

| Reference | 01976 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2023 (18th session) |

| List | Good Safeguarding Practices |

The nyckelharpa (Swedish: [ˈnʏ̂kːɛlˌharːpa], plural nyckelharpor), meaning "keyed fiddle" or "key harp"(lit.), is a "keyed" bowed chordophone, primarily originating from Sweden in its modern form, but with its roots in Medieval Europe. It is similar in appearance to a fiddle or violin but larger (in its earlier forms essentially a modified vielle), which employs key-actuated tangents along the neck to change the pitch during play, much like a hurdy-gurdy. The keys slide under the strings, with the tangents set perpendicularly to the keys, reaching above the strings. Upon key-actuation, the tangent is pressed to meet the corresponding string, much like a fret, shortening its vibrating length to that point, changing the pitch of the string.[1][2] It is primarily played underarm, suspended from the shoulder using a sling, with the bow in the overhanging arm.

The origin of the instrument is unknown, but its historical foothold and modern development is much larger in Sweden than other countries. Many of the early historical depictions of the instrument are found in Sweden, the earliest possibly depiction found on a relief located on a 14th century church portal. While historically not too common an instrument in Sweden (relatively speaking), the violin outshining it in usage among spelmän (players of Swedish folk music), the nyckelharpa became a popular folk instrument in the Swedish province of Uppland during the 17th century, subsequently leading to its popularization and spread throughout Sweden the following centuries. By the 19th century it had become a "fine" instrument, being played at concerts in Stockholm,[3] and by the early 20th century it had become an archetypal instrument alongside the violin for Swedish folk music. Today it is considered by many to be the quintessential national instrument of Sweden.[4] The oldest surviving nyckelharpa is dated 1526 and is part of the Zorn Collections in Mora Municipality, Sweden.[3]

Besides Sweden, early depictions of nyckelharpor can also be found in Denmark, Germany and Italy, among other European countries. The earliest of these is found in a 1408 fresco by Taddeo di Bartolo at the Palazzo Pubblico chapel in Siena, Italy, which depicts an angel playing a "keyed viola". Recently there has been a push by luthiers and the like to make recreations of these older depictions of nyckelharpor, akin to reconstructional archaeology,[5] but also new instruments based on the nyckelharpa concept of a keyed bow instrument.[6]

History

[edit]1000s–1200s (first keyed instruments)

[edit]

Development of keyed string instruments appears to have started during the High Middle Ages, with instruments such as the duo-played organistrum (a hurdy-gurdy), starting in the late 900s or early 1000s. Such were popular in Southwestern Europe and eventually evolved into the solo-played "symphonia"-hurdy-gurdy in France or Spain in the 1200s, featuring diatonic tangents. Somewhere along the line, it appears the keyed section of a "hurdy-gurdy" was integrated onto a bowed string instrument, producing the first keyed fiddle or proto-nyckelharpa instrument. It is unclear were the instrument first appeared, but the spread of hurdy-gurdy and bowed string instruments in Europe during the later Middle Ages makes it possible that the instrument was invented independently by several people.

1300s–1500s (first keyed vielles)

[edit]

The earliest possible depiction of nyckelharpor known, or rather "keyed vielles" by appearance, can be found in a relief on one of the portals to the Källunge Church, located on the Swedish island of Gotland. Dating from circa 1350, it depicts two musicians with bow stringed instruments suspiciously looking like nyckelharpor, appearing to have keyboxes (a cover above the strings) like a hurdy-gurdy. The relief is however eroded and damaged from time, making it hard to confirm them as nyckelharpor.[7][8]

The earliest confirmed depiction of a nyckelharpa appears in an Italian church painting found in Siena, Italy, dating to 1408. It depicts an angel playing a vielle-looking nyckelharpa (a common nyckelharpa motif for the period), featuring five keyes and a keybox above the strings.

Throughout the 15th century, more depictions of nyckelharpor start appearing in church paintings, notably in Swedish and Danish churches, such as the Emmislöv Church, which has a painting of a nyckelharpa musician dating to 1450–1475.[9] Others include the Tolfta Church in Sweden, which has two paintings of angels playing nyckelharpa, dating to c. 1460–1525. Interestingly, most, if not all, Swedish nyckelharpa depictions on church paintings, lack keyboxes.[9] Early Danish nyckelharpa depictions, such as the ones found in the Rynkeby Church, dated to ca. 1560, all feature keyboxes.[9]

-

Angel with nyckelharpa, fresco in the church at Tolfa, Tierp Municipality, Uppland, Sweden. Unknown painter, 1503.

-

Angel with nyckelharpa, fresco in the church at Tolfa, Tierp Municipality, Uppland, Sweden. Unknown painter, 1503.

-

Angel with nyckelharpa, fresco in the Rynkeby church, Denmark. Unknown painter, ca. 1560.

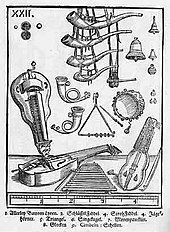

The earliest known recorded name for nyckelharpor can be found in an early German music dictionary (German: Musiklexikon) by Martin Agricola, dating to 1529. There it is called a Schlüsselfidel ("key vielle").[9] The corresponding image features a keybox on the instrument.[9]

1600s–1800s (early modern period)

[edit]

The german term, Schlüsselfidel, is mentioned in Theatrum Instrumentorum, a famous work written in 1620 by the German organist Michael Praetorius (1571–1621). At this time the nyckelharpa was not too common of an instrument in Sweden, the violin outshining it in Swedish folk music use.

Starting from the early 17th century, however, the nyckelharpa got a foothold as a popular folk instrument among spelmän (players of Swedish folk music) in the Swedish province of Uppland, which came to be the stronghold for nyckelharpa music the following centuries, including musicians like Byss-Calle (Carl Ersson Bössa, 1783–1847) from Älvkarleby.[8] From Uppland, the popularization of the instrument spread to the neighbouring provinces and eventually throughout Sweden. By the 19th century it had become a "fine" instrument which came to be played at concerts in Stockholm.[3]

-

The folk life painting Spelande bönder (playing farmers), by JJ Malmberg, 1863, depicting a farmer with a nyckelharpa

-

A folk life painting by JJ Malmberg from 1964, depicting a spelman with a nyckelharpa

-

Nyckelharpist Johan Edlund (1829–1903), with a kontrabasharpa

-

Spelman with nyckelharpa around the turn of the century, 1900

1900s–onward (modern period)

[edit]

The popularization of the nyckelharpa continued and by the early 20th century it had become an archetypal instrument for Swedish folk music, equivalent to the violin. From this point the instrument would see a wide range of developments to make it a more modern instrument for a modern audience.

Changes by August Bohlin (1877–1949) in 1929/1930 made the nyckelharpa a chromatic instrument with a straight bow, making it a more violin-like and no longer a bourdon instrument.[8] Composer, player and maker of nyckelharpor Eric Sahlström (1912–1986) used this new instrument and helped to re-popularize it in the mid-20th century.[8] In spite of this, the nyckelharpa's popularity declined until the 1960s roots revival.[citation needed]

The 1960s and 1970s saw a resurgence in the popularity of the nyckelharpa, with notable artists such as Marco Ambrosini (Italy and Germany), Sture Sahlström, Gille, Peter Puma Hedlund and Nils Nordström including the nyckelharpa in both early music and contemporary music offerings. Continued refinement of the instrument also contributed to the increase in popularity, with instrument builders like Jean-Claude Condi and Annette Osann bringing innovation to the bow and body.[10]

In 1990s, the nyckelharpa was recognised as one of the instruments available for study at the folk music department of the Royal College of Music in Stockholm (Kungliga Musikhögskolan). It has also been a prominent part of several revival groups in the later part of the century, including the trio Väsen, the more contemporary group Hedningarna, the Finnish folk music group Hyperborea and the Swedish folk music groups Dråm and Nordman. It has also been used in non-Scandinavian musical contexts, for example by the Spanish player Ana Alcaide, the English singer and multi-instrumentalist Anna Tam, and Sandra Schmitt of Storm Seeker, a pirate metal band from Germany.[citation needed]

The first World Nyckelharpa Day[11] took place on 26 April 2020 just as the world had gone into lockdown. All the events took place online, either as livestreams or pre-recorded videos on Youtube. This now is a yearly event taking place on the Sunday closest to 26 April – this being the birthday of the great nyckelharpa player Byss-Calle. The event is co-ordinated by British/Swedish nyckelharpa player Vicki Swan.[12][13]

English composer Natalie Holt used nyckelharpa for background score of the Disney+ series Loki from 2021.[14]

Eurovision Song Contest 1995 winner Norway's song "Nocturne" (Secret Garden Group) used this instrument in their performance.[15]

Reconstructional archaeology

[edit]In the 21st century there has been a growing interest among enthusiast to resurrect the early historical nyckelharpa designs. This has led to countless recreations of preserved historical copies, such as the moraharpa and esseharpa,[16] among others, but also a push to recreate nyckelharpa-designs only found in historical paintings, such as the one depicted in Siena, Italy. Such projects can be seen as reconstructional archaeology, although reproductions are not always 1–1 clones of what is depicted in the old paintings.

The nyckelharpa depicted in Siena, Italy, has been dubbed viola a chiavi di Siena (Italian for "Sienan keyed viola"), or simply Siena-Harpa (also styled Sienaharpa) for short, relating to the Swedish naming-theme ("Siena harp"), and such a reconstruction was produced as part of an international research project around 2020, built by professional luthier Alexander Pilz, a seasoned maker of nyckelharpor working out of Leipzig, Germany.[5] The popularisation of the Italian design has led other luthiers in recent years to produce reproductions of the depiction as well.[17]

Technique

[edit]

The nyckelharpa is usually played with a strap around the neck, stabilised by the right arm. Didier François, a violinist and nyckelharpist from Belgium, is noted for using an unusual playing posture, holding the nyckelharpa vertically in front of the chest. This allows a wider range of motion for both arms. It also affects the tone and sound of the instrument.

Some players may use a violin bracket to keep the nyckelharpa away from the body so that it can swing freely, causing it to sound more "open" as its resonance is not damped.[citation needed]

Each nyckelharpa string is either a melody string, drone, or (in some instruments) resonance string. Melody strings are stopped using the keys, so different notes can be played when the string is bowed, depending on which key is depressed. Each key specifically stops one melody string. Drone strings are bowed but not stopped, so only one note can be played with them. Resonance strings are neither bowed nor stopped. They add to the timbre of the instrument by resonating in sympathy when the same note is played by bowing another string.

Variants

[edit]There are several variants of the nyckelharpa being produced and played today, differing in the number and arrangement of keys, number and arrangement of strings, and general body shape. They can be divided into types "with resonance strings" and types "without resonance strings".[18][19][20][21] There are also a variety of derivatives which belongs to the "keyed bowed chordophone-family" but do not necessarily have to be classified as nyckelharpor.[6]

Listed types below refer to Swedish/Nordic types as "variants", with other types being referred to as "derivatives".

Variants with resonance strings

[edit]The most common types of nyckelharpor are distinguished by having resonance strings. They can be divided into several subvariants, but the four main variants are as follows:[20][21]

- Kromatisk nyckelharpa ("chromatic key harp") – most predominant type of nyckelharpa. The three-row so-called "chromatic nyckelharpa", with three melody strings tuned A1 – C1 – G, one drone tuned at C (from the highest to the lowest string) that is only touched occasionally, and 12 resonance strings (one for each step of the chromatic scale).

- Kontrabasharpa ("double bass harp") – most popular during the 17th and 18th centuries. Typically the top has a high arch, and there are two oval-shaped soundholes in the lower bout called oxögon. The name "Kontrabasharpa" refers not to the pitch being any deeper than a standard nyckelharpa's (it isn't), but to the unstopped drone string which always resonates below the melody strings during regular play. The two melody strings are set up on either side of the drone string, such that melodies can be played as double stops between a single melody string and the open drone string without the two melody strings ever clashing.

- Silverbasharpa ("silver base harp") – most popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries, so named because of the bass strings which are traditionally wound with silver. It is the immediate predecessor to the modern nyckelharpa, and the string configuration is identical, however it retains the older top with a more pronounced arch as well as the two oxögon. The main difference is that only the top two strings are stopped, meaning that the bottom C and G strings cannot play any other notes, and so nearly all of its repertoire is in the key of C. In addition, some silverbasharpor may be diatonic and not chromatic, and some keys may stop both melody strings at once.[22]

- Oktavharpa ("octave harp") – invented by Lennart and Johan Hedin in 1996. It is essentially a modern three-row nyckelharpa tuned an octave down, almost identical to a cello. It is the lowest-pitched variant of the nyckelharpa.

The resonance strings, or sympathetic strings, which were added to the instrument during the 2nd half of the 16th century, are not bowed directly but resonate with the other strings. There can be anywhere from six to twelve of them, depending on the construction and tonality of the instrument. Some modern nyckelharpor have been made with four or even five rows of keys, however they have not been popular enough to replace the three-row nyckelharpa as the standard.

Variants without resonance strings

[edit]Beyond the common variants with resonance strings, there are a variety of nyckelharpa designs without such. Some of examples include:

- Moraharpa ("Mora harp") – is the most common nyckelharpa derivative, based on a unique nyckelharpa found in the Swedish town of Mora Municipality, Sweden, dating to 1526 (although presumed to be from the later 17th century). This design has a straight bridge, one melody string, two drone strings, and one row of keys, with a body resembling a lute.

- Esseharpa (Swedish for "Esse harp") or ähtävän harppu (Finnish for "Ähtävä harp") – Finnish/Fenno-Swedish nyckelharpa derivative, based on nyckelharpa examples from Fenno-Swedish former municipality Esse (Finnish: Ähtävä) in the Finnish region of Ostrobothnia (Swedish: Österbotten). It is small and cone-shaped with four (sometimes three) strings and one row of ten to fifteen keys.[18][16]

- Vefsenharpa ("Vefsn harp") – Norwegian nyckelharpa derivative, based on nyckelharpa examples from Vefsn Municipality (Swedish: Vefsen) in Nordland county, Norway. Similar to the Esseharpa but with inward curves on the body.[18]

Derivatives

[edit]- Viola a chiavi di Siena ("Sienan keyed viola") or Siena-Harpa ("Siena harp") for short – is a nyckelharpa derivative based on the previously mentioned 1408 fresco by Taddeo di Bartolo at the Palazzo Pubblico chapel in Siena, Italy, featuring an angel playing a nyckelharpa. As part of reconstructional archaeology, this recreated design has three melody strings, one drone string, and one row of keys.[5][17]

- Viola d'amore a chiavi ("keyed viola d'amore") – is a nyckelharpa derivative seemingly invented by professional luthier Alexander Pilz, a seasoned maker of nyckelharpor from Leipzig, Germany. It has gut strings and is specially built for renaissance-baroque music. It has a different sound than traditional Swedish Nyckelharpor, closer to the viola da gamba, and therefore has the name "keyed viola d'amore".[6]

Gallery

[edit]-

Schlüsselfidel at the "Knochenhaueramtshaus", Hildesheim, Germany, 1529

-

Bronwyn Bird, member of Blue Moose, plays the nyckelharpa at a concert in 2007. Photo by Georgie Grd.

-

Marco Ambrosini at Burg Fürsteneck, Germany, playing a nyckelharpa built by Annette Osann

-

Didier François teaching his special technique at the International Days of the Nyckelharpa at Burg Fürsteneck, 2023

-

Mia Gundberg Ådin (Huldrelokkk) playing the Nyckelharpa at the music festival Bardentreffen in Nuremberg, 2015

Further reading

[edit]- Gunner Ahbäck; Gunner Fredelius. "Different typologies for the nyckelharpa, typologies and terminologies in short (Olika typologier för nyckelharpan, typologier och terminologi i korta drag)". nyckelharpansforum.net (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2003-06-26. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- Gunnar Ahlbäck; Gunnar Fredelius. "Nyckelharpans typologi" (in Swedish). nyckelharpansforum.net. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- "Nyckelharpa History".

- "Nyckelharpa – olov johansson".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ternhag, Gunnar; Boström, Mathias. "The Dissemination of the Nyckelharpa – The Ethnic and the non-Ethnic Ways". STM-Online vol. 2 (1999). Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Nyckelharpa". nyckelharpa.org. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ a b c "Nyckelharpan som nationalinstrument". riksdagen.se. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "National Instruments of Sweden". folkways.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ a b c "The "Siena-Harpa" Project". marcoambrosini.eu. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ a b c "Viola d'amore a chiavi". nyckelharpa.be. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Brashers, Bart. "A Brief History of the Nyckelharpa". American Nyckelharpa Association. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Broughton, Simon; Ellingham, Mark; Lusk, Jon (28 September 2006). The Rough Guide to World Music Vol. 1: Africa and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8.

- ^ a b c d e "history-of-the-nyckelharpa_per-ulf-allmo-de.pdf" (PDF). nyckelharpa.eu (in German). Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ "Nyckleharpa History". www.nyckelharpa.org. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "World Nyckelharpa Day – Sunday 23 April 2023".

- ^ "The Nyckelharpa Effect – Virtual and in Real life Nyckelharpa Learning".

- ^ "2020 – World Nyckelharpa Day". Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (2021-07-01). "The Weird, Unsettling Music of Loki: Composer Natalie Holt Breaks Down the Marvel Series' Score". Variety. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ Nocturne - Secret Garden - Norway 1995 - Eurovision songs with live orchestra. Retrieved 2024-05-11 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b "Soittimet". kansanmusiikinmatkassa.blogspot.com (in Finnish). Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ a b "fiddle klawiszowe". lucjankosciolek.wixsite.com (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-05-01.

Rekonstrukcja instrumentu z fresku znajdującego się w Palazzo Pubblico w Sienie we Włoszech, namalowanego przez Taddeo di Bartolo w 1408 roku. Instrument sopranowy o skali skrzypiec w pierwszej pozycji.

- ^ a b c Gunnar Ahlbäck; Gunnar Fredelius. "Different typologies for the nyckelharpa, typologies and terminologies in short (Olika typologier för nyckelharpan, typologier och terminologi i korta drag)". nyckelharpansforum.net (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2003-06-26. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Gunnar Ahlbäck; Gunnar Fredelius. "Nyckelharpans typologi" (in Swedish). nyckelharpansforum.net. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ a b "Nyckelharpa History".

- ^ a b "Nyckelharpa – olov johansson".

- ^ "The Nyckelharpa". nyckelharpansforum.net. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

External links

[edit]- "home". The American Nyckelharpa Association.

- "International Days of the Nyckelharpa at BURG FÜRSTENECK (Germany) – workshop, concert, conference, exhibition, seminar and exchange of experience".

- "Nyckelharpa in Europe – The European Nyckelharpa Cooperation". www.nyckelharpa.eu.

- Kornel Mariusz Radwanski plays The Alchemist's Dance on nyckelharpa with James Kline on archharp-guitar on YouTube

- "Nyckelharpa Workshops and Teaching in the UK".

- What is a Nyckelharpa? on YouTube