Kellogg–Briand Pact

This article needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. In particular, it has problems with MOS:INFOBOXFLAG. (January 2024) |

| General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy | |

|---|---|

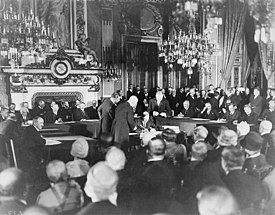

Kellogg–Briand Pact with signatures | |

| Signed | 27 August 1928 |

| Location | Quai d'Orsay, Paris, France |

| Effective | 24 July 1929 |

| Negotiators | |

| Parties |

31 signatories by effective date 25 countries once in force

|

| Full text | |

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy[1] – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war to resolve "disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them".[2] The pact was signed by Germany, France, and the United States on 27 August 1928, and by most other states soon after. Sponsored by France and the U.S., the Pact is named after its authors, United States Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The pact was concluded outside the League of Nations and remains in effect.[3]

A common criticism is that the Kellogg–Briand Pact did not live up to all of its aims but has arguably had some success.[4] It was unable to prevent the Second World War but was the basis for trial and execution of wartime German leaders in 1946. Furthermore, declared wars became very rare after 1945.[5] It has been ridiculed for its moralism, legalism, and lack of influence on foreign policy. The pact had no mechanism for enforcement, and many historians and political scientists see it as mostly irrelevant and ineffective.[6] Nevertheless, the pact served as the legal basis for the concept of a crime against peace, for which the Nuremberg Tribunal and Tokyo Tribunal tried and executed the top leaders responsible for starting World War II.[7][8]

Similar provisions to those in the Kellogg–Briand Pact were later incorporated into the Charter of the United Nations and other treaties, which gave rise to a more activist American foreign policy which began with the signing of the pact.[9]

Text

[edit]The main text is very short:[2]

Article I

The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies and renounce it as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another.

Article II

The High Contracting Parties agree that the settlement or solution of all disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them, shall never be sought except by pacific means.

Parties

[edit]

The plan was devised by American lawyers Salmon Levinson and James T. Shotwell, and promoted by Senator William E. Borah.[10]

Borah and U.S. diplomat William Richards Castle Jr., Assistant Secretary of State, played key roles after Kellogg and Briand agreed on a two party treaty between the U.S. and France.[11] It was originally intended as a bilateral treaty, but Castle worked to expand it to a multinational agreement that included practically the entire world. Castle managed to overcome French objections through his discussions with the French ambassador, replacing the narrow Franco-American agreement with a treaty that attracted almost all major and minor nations.[12]

The pact was first signed on 27 August 1928 in Paris at the French Foreign Ministry by the representatives from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, India, the Irish Free State, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa, and the United States. It took effect on 24 July 1929.

By that date, the following nations had deposited instruments of ratification of the pact:

- Afghanistan

- Albania

- Austria

- Bulgaria

- China

- Cuba

- Denmark

- Egypt

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Finland

- Guatemala

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Netherlands

- Nicaragua

- Norway

- Panama

- Peru

- Portugal

- Romania

- Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

- Siam

- Soviet Union

- Spain

- Sweden

- Turkey

12 additional parties joined after that date: Persia, Greece, Honduras, Chile, Luxembourg, Danzig, Costa Rica, Mexico, Venezuela, Paraguay, Switzerland and the Dominican Republic[2] for a total of 57 state parties by 1929. Six states joined between 1930 and 1934: Haiti, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, Iraq and Brazil. After the Second World War, Barbados declared its accession to the treaty in 1971,[13] followed by Fiji (1973), Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica (both 1988), the Czech Republic and Slovakia (after Czechoslovakia dissolved in 1993), and, as a result of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Slovenia (1992), Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia (both in 1994).[14] The Free City of Danzig, which had joined the Pact in 1929, ceased to exist in 1939 and became a regular part of Poland after World War II.

In the United States, the Senate approved the treaty 85–1, with only Wisconsin Republican John J. Blaine voting against over concerns with British imperialism.[15] While the U.S. Senate did not add any reservations to the treaty, it did pass a measure which interpreted the treaty as not infringing upon the United States' right of self-defense and not obliging the nation to enforce it by taking action against those who violated it.[16]

-

French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand speaking

-

German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann signing

-

Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs Mackenzie King signing

Effect and legacy

[edit]The 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact was concluded outside the League of Nations and remains in effect.[3] One month following its conclusion, a similar agreement, the General Act for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, was concluded in Geneva, which obliged its signatory parties to establish conciliation commissions in any case of dispute.[17] With the signing of the Litvinov Protocol in Moscow on February 9, 1929, the Soviet Union and its western neighbors, including Romania, agreed to put the Kellogg–Briand Pact in effect without waiting for other western signatories to ratify.[18] The Bessarabian question had made agreement between Romania and the Soviet Union challenging and dispute between the nations over Bessarabia continued.[19][20] The pact's central provisions renouncing the use of war, and promoting peaceful settlement of disputes and the use of collective force to prevent aggression, were incorporated into the United Nations Charter and other treaties. Although civil wars continued, wars between established states have been rare since 1945, with a few major exceptions such as the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and various conflicts in the Middle East.[9]

As a practical matter, the Kellogg–Briand Pact did not live up to its primary aims, but has arguably had some success. It did not end war or stop the rise of militarism, and was unable to keep the international peace in succeeding years. Its legacy remains as a statement of the idealism expressed by advocates for peace in the interwar period.[21] However, it also helped to erase the legal distinction between war and peace, because the signatories, having renounced the use of war, began to wage wars without declaring them, as in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939, and the German and Soviet invasions of Poland.[22]

The popular perception of the Kellogg–Briand Pact was best summarized by Eric Sevareid who, in a nationally televised series on American diplomacy between the two world wars, referred to the pact as a "worthless piece of paper".[9] In his history of Europe from 1914 to 1948, historian Ian Kershaw referred to the Pact as "vacuous" and said that it was "a dead letter from the moment it was signed."[23]

While the Pact has been ridiculed for its moralism and legalism and lack of influence on foreign policy, it did lead to a more activist American foreign policy.[9] Legal scholars Scott J. Shapiro and Oona A. Hathaway have argued that the Pact inaugurated "a new era of human history" characterized by the decline of inter-state war as a structuring dynamic of the international system. According to Shapiro and Hathaway one reason for the historical insignificance of the pact was the absence of an enforcement mechanism to compel compliance from signatories, since the pact only calls for violators to "be denied of the benefits furnished by [the] treaty". They also said that the Pact appealed to the West because it promised to secure and protect previous conquests, thus securing their place at the head of the international legal order indefinitely.[24] They wrote in 2017:

As its effects reverberated across the globe, it reshaped the world map, catalyzed the human rights revolution, enabled the use of economic sanctions as a tool of law enforcement, and ignited the explosion in the number of international organizations that regulate so many aspects of our daily lives.[25][26]

Hathaway and Shapiro show that between 1816 and 1928 there was on average one military conquest every ten months. After 1945, in very sharp contrast, the number of such conflicts declined to one in every four years.[27]

The pact, in addition to binding the particular nations that signed it, has also served as one of the legal bases establishing the international norms that the threat[28] or use of military force in contravention of international law, as well as the territorial acquisitions resulting from it,[29] are unlawful. The interdiction of aggressive war was confirmed and broadened by the United Nations Charter, which provides in article 2, paragraph 4, that "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations." One legal consequence is that it is unlawful to annex territory by force, although other forms of annexation have not been prevented. More broadly, there is now a strong presumption against the legality of using, or threatening, military force against another country. Nations that have resorted to the use of force since the Charter came into effect have typically invoked self-defense or the right of collective defense.[30]

Notably, the pact also served as the legal basis for the concept of a crime against peace. It was for committing this crime that the Nuremberg Tribunal and Tokyo Tribunal tried and executed the top leaders responsible for starting World War II.[7]

Political scientists Julie Bunck and Michael Fowler in 2018 argued that the Pact was:

an important early venture in multilateralism. ... [I]nternational law evolved to circumscribe the use of armed force with legal restrictions. The forcible acquisition of territory by conquest became illegitimate and individual criminal liability might attach to those who pursued it. In criminalizing war Kellogg–Briand played a role in the development of a new norm of behavior in international relations, a norm that continues to play a role in our current international order.[31]

See also

[edit]- Geneva Protocol (1924)

- Anti-Comintern Pact

- Four-Power Pact

- Pact of Steel

- Tripartite Pact

- Washington Naval Treaty

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ See certified true copy of the text of the treaty in League of Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 94, p. 57 (No. 2137)

- ^ a b c Kellogg–Briand Pact 1928, Yale University

- ^ a b Westminster, Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons. "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 16 Dec 2013 (pt 0004)". publications.parliament.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marsh, Norman S. (1963). "Book Reviews". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 12 (3): 1049–1050. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/12.3.1049. ISSN 0020-5893.

- ^ Bunck, Julie M., and Michael R. Fowler. "The Kellogg–Briand Pact: A Reappraisal". Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law, vol. 27, no. 2, Spring 2019, pp. 229–276. HeinOnline.

- ^ "There's Still No Reason to Think the Kellogg–Briand Pact Accomplished Anything". Foreign Policy. 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b Kelly Dawn Askin (1997). War Crimes Against Women: Prosecution in International War Crimes Tribunals. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 46. ISBN 978-9041104861.

- ^ Binoy Kampmark, "Punishing wars of aggression: conceptualising Nazi State criminality and the US policy behind shaping the crime against peace, 1943–1945." War & Society (2018) 37#1 pp. 38–56.

- ^ a b c d Josephson, Harold (1979). "Outlawing War: Internationalism and the Pact of Paris". Diplomatic History. 3 (4): 377–390. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1979.tb00323.x.

- ^ Oona A. Hathaway, and Scott J. Shapiro, The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World (2017) p. xxi, 114.

- ^ Charles DeBenedetti, "Borah and the Kellogg–Briand Pact." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 63.1 (1972): 22–29.

- ^ Robert H. Ferrell, Peace in Their Time: The Origins of the Kellogg–Briand Pact (Yale University Press, 1952) pp. 140–143.

- ^ "UNTC". treaties.un.org.

- ^ "US Department of State" (PDF). state.gov.

- ^ "John James Blaine Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Dictionary of Wisconsin History. Accessed 11 November 2008.

- ^ "The Avalon Project : The Kellogg–Briand Pact – Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Relations United States". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- ^ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 93, pp. 344–363.

- ^ Deletant, Dennis (2006). Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonsecu and his Regime, Romania, 1940–1944. Springer. ISBN 0230502091. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ von Rauch, Georg (1962). A History of Soviet Russia. Praeger. p. 208. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ King, Charles (2013). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture. Hoover Institution Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0817997939. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Milestones: 1921–1936 – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov.

- ^ Quigley, Carroll (1966). Tragedy And Hope. New York: Macmillan. pp. 294–295.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (2016). To Hell and Back: Europe 1914–1949. New York: Penguin Books. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-14-310992-1.

- ^ Menand, Louis (18 September 2017). "Drop Your Weapons". The New Yorker. Condé Nast.

- ^ Hathaway, Oona A.; Shapiro, Scott J. (2017). The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World. Simon and Schuster. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-5011-0986-7.

- ^ For detailed discussion by several scholars see [H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXI-15 "https://issforum.org/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XXI-15.pdf"]

- ^ Hathaway and Shapiro, The Internationalists pp 311–335.

- ^ Article 2, Budapest Articles of Interpretation Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine (see under footnotes), 1934

- ^ Article 5, Budapest Articles of Interpretation Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine (see under footnotes), 1934

- ^ Silke Marie Christiansen (2016). Climate Conflicts – A Case of International Environmental and Humanitarian Law. Springer. p. 153. ISBN 978-3319279459.

- ^ Julie M. Bunck, and Michael R. Fowler. "The Kellogg–Briand Pact: A Reappraisal." Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law 27 #2(2018): 229–276 online

Bibliography

- Bunck, Julie M., and Michael R. Fowler. "The Kellogg–Briand Pact: A Reappraisal." Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law 27 #2(2018): 229–276 online, a major scholarly survey.

- Carroll, Francis M. "War and Peace and International Law: The Kellogg–Briand Peace Pact Reconsidered." Canadian Journal of History (2018) 53#1 : 86–96.

- Cavendish, Richard. "The Kellogg–Briand Pact Aims to Bring an End to War". History Today 58.8 (2008): 11+.

- DeBenedetti, Charles. "Borah and the Kellogg–Briand Pact." The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 63.1 (1972): 22–29.

- Ellis, Lewis Ethan. Frank B. Kellogg and American foreign relations, 1925–1929 (1961). online

- Ellis, Lewis Ethan. Republican Foreign Policy, 1921–1933 (1968). online

- Ferrell, Robert H. (1952). Peace in Their Time: The Origins of the Kellogg–Briand Pact. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0393004915.

- "H-Diplo Roundtable XXI-15 on The Internationalists" online

- Hathaway, Oona A. and Shapiro, Scott J. "International law and its transformation through the outlawry of war". International Affairs (2019) 95#1 pp 45–62

- Hathaway, Oona A., and Scott J. Shapiro. "International law and its transformation through the outlawry of war." International Affairs (2019) 95#1 pp 45–62. Argues for a major impact – that this prohibition is key to understanding international law and state behavior in the last century.

- Johnson, Gaynor. "Austen Chamberlain and the Negotiation of the Kellogg–Briand Pact, 1928" in Gaynor Johnson, ed. Locarno Revisited: European Diplomacy 1920–1929. (Routledge, 2004) pp 54–67.

- Jones, E. Stanley. The Pact Of Paris Officially The General Pact For The Renunciation Of War (1929) online

- Josephson, Harold. "Outlawing war: Internationalism and the Pact of Paris." Diplomatic History 3.4 (1979): 377–390.

- Kampmark, Binoy. "Punishing wars of aggression: conceptualising Nazi State criminality and the US policy behind shaping the crime against peace, 1943–1945." War & Society (2018) 37#1 pp 38–56.

- Limberg, Michael. "'In Relation to the Pact': Radical Pacifists and the Kellogg–Briand Pact, 1928–1939". Peace & Change 39.3 (2014): 395–420.

- Miller, David Hunter. The Pact of Paris – A Study of the Briand–Kellogg Treaty (1928)

- Shotwell, James T. War as an instrument of national policy : and its renunciation in the pact of Paris (1929) online

- Swanson, David. When the World Outlawed War (2011). [ISBN missing]

External links

[edit] Works related to Kellogg–Briand Treaty at Wikisource

Works related to Kellogg–Briand Treaty at Wikisource

- 1928 in France

- Aggression in international law

- Interwar-period treaties

- Law of war

- Nuremberg trials

- Peace treaties

- Presidency of Calvin Coolidge

- Treaties concluded in 1928

- Treaties entered into force in 1929

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of British India

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Czechoslovakia

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Pahlavi Iran

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of Spain under the Restoration

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of the Albanian Republic

- Treaties of the Ditadura Nacional

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of the Empire of Japan

- Treaties of the Ethiopian Empire

- Treaties of the First Austrian Republic

- Treaties of the Free City of Danzig

- Treaties of the French Third Republic

- Treaties of the Irish Free State

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Afghanistan

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Bulgaria

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Egypt

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

- Treaties of the Netherlands

- Treaties of the Republic of China (1912–1949)

- Treaties of the Second Hellenic Republic

- Treaties of the Second Polish Republic

- Treaties of the Soviet Union

- Treaties of the Union of South Africa

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of the Weimar Republic

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Eponymous treaties