Amlodipine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /æmˈloʊdɪˌpiːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Norvasc, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a692044 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Drug class | Calcium channel blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 64–90% |

| Protein binding | 93%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Metabolites | Various inactive pyrimidine metabolites |

| Onset of action | Highest availability 6–12 hours after oral dose[10] |

| Elimination half-life | 30–50 hours |

| Duration of action | At least 24 hours[10] |

| Excretion | Urine[10] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.102.428 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

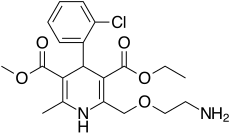

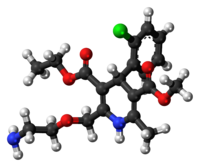

| Formula | C20H25ClN2O5 |

| Molar mass | 408.88 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amlodipine, sold under the brand name Norvasc among others, is a calcium channel blocker medication used to treat high blood pressure, coronary artery disease (CAD)[10] and variant angina (also called Prinzmetal angina or coronary artery vasospasm, among other names).[11] It is taken orally (swallowed by mouth).[10]

Common side effects include swelling, feeling tired, abdominal pain, and nausea.[10] Serious side effects may include low blood pressure or heart attack.[10] Whether use is safe during pregnancy or breastfeeding is unclear.[2][10] When used by people with liver problems, and in elderly individuals, doses should be reduced.[10] Amlodipine works partly by vasodilation (relaxing the arteries and increasing their diameter).[10] It is a long-acting calcium channel blocker of the dihydropyridine type.[10]

Amlodipine was patented in 1982, and approved for medical use in 1990.[12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[13] It is available as a generic medication.[10][14] In 2022, it was the fifth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 70 million prescriptions.[15][16] In Australia, it was one of the top 10 most prescribed medications between 2017 and 2023.[17]

Medical uses

[edit]Amlodipine is used in the management of hypertension (high blood pressure)[18] and coronary artery disease in people with either stable angina (where chest pain occurs mostly after physical or emotional stress)[19] or vasospastic angina (where it occurs in cycles) and without heart failure. It can be used as either monotherapy or combination therapy for the management of hypertension or coronary artery disease. Amlodipine can be administered to adults and to children 6–17 years of age.[7]

Calcium channel blockers, including amlodipine, may provide greater protection against stroke than beta blockers.[20] [21] Evidence from two meta-analyses has reported no significant difference between calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics [22] [20] and angiotensin receptor blockers[22] in stroke protection while one 2015 meta-analysis has suggested that calcium channel blockers offer greater protection against stroke than other classes of antihypertensive.[21]

Amlodipine along with other calcium channel blockers are considered the first choice in the pharmacological management of Raynaud's phenomenon.[23][24]

Combination therapy

[edit]Amlodipine can be given as a combination therapy with a variety of medications:[10][25]

- Amlodipine/atorvastatin, where amlodipine is given for hypertension or CAD and atorvastatin prevents cardiovascular events, or if the person also has high cholesterol.

- Amlodipine/aliskiren or amlodipine/aliskiren/hydrochlorothiazide if amlodipine alone cannot reduce blood pressure. Aliskiren is a renin inhibitor, which works to reduce primary hypertension (that with no known cause) by binding to renin and preventing it from initiating the renin–angiotensin system (RAAS) pathway to increase blood pressure. Hydrochlorothiazide is a diuretic and decreases overall blood volume.

- Amlodipine/benazepril if either drug has failed individually, or amlodipine alone caused edema. Benazepril is an ACE inhibitor and blocks the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II in the RAAS pathway.

- Amlodipine/celecoxib

- Amlodipine/lisinopril

- Amlodipine/olmesartan or amlodipine/olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide if amlodipine is insufficient in reducing blood pressure. Olmesartan is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist and blocks part of the RAAS pathway.

- Amlodipine/perindopril if using amlodipine alone caused edema. Perindopril is a long-lasting ACE inhibitor.

- Amlodipine/telmisartan, where telmisartan is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.

- Amlodipine/valsartan or amlodipine/valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, where valsartan is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.

Contraindications

[edit]The only absolute contraindication to amlodipine is an allergy to amlodipine or any other dihydropyridines.[7]

Other situations occur, however, where amlodipine generally should not be used. In patients with cardiogenic shock, where the heart's ventricles are not able to pump enough blood, calcium channel blockers exacerbate the situation by preventing the flow of calcium ions into cardiac cells, which is required for the heart to pump.[26] While use in patients with aortic stenosis (narrowing of the aorta where it meets the left ventricle) since it does not inhibit the ventricle's function is generally safe, it can still cause collapse in cases of severe stenosis.[27] In unstable angina (excluding variant angina), amlodipine can cause a reflex increase in cardiac contractility (how hard the ventricles squeeze) and heart rate, which together increase the demand for oxygen by the heart itself.[28] Patients with severe hypotension can have their low blood pressure exacerbated, and patients in heart failure can get pulmonary edema. Those with impaired liver function are unable to metabolize amlodipine to its full extent, giving it a longer half-life than typical.[7][6]

Amlodipine's safety in pregnancy has not been established, although reproductive toxicity at high doses is known. Whether amlodipine enters the milk of breastfeeding mothers is also unknown.[7][6]

Those who have heart failure, or recently had a heart attack, should take amlodipine with caution.[29]

Adverse effects

[edit]

Some common dose-dependent adverse effects of amlodipine include vasodilatory effects, peripheral edema, dizziness, palpitations, and flushing.[7][30] Peripheral edema (fluid accumulation in the tissues) occurs at rate of 10.8% at a 10-mg dose (versus 0.6% for placebos), and is three times more likely in women than in men.[7] It causes more dilation in the arterioles and precapillary vessels than the postcapillary vessels and venules. The increased dilation allows for more blood, which is unable to push through to the relatively constricted postcapillary venules and vessels; the pressure causes much of the plasma to move into the interstitial space.[31] Amlodipine-association edema can be avoided by adding ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonist.[10] Of the other dose-dependent side effects, palpitations (4.5% at 10 mg vs. 0.6% in placebos) and flushing (2.6% vs. 0%) occurred more often in women; dizziness (3.4% vs. 1.5%) had no sex bias.[7]

Common but not dose-related adverse effects are fatigue (4.5% vs. 2.8% with a placebo), nausea (2.9% vs. 1.9%), abdominal pain (1.6% vs. 0.3%), and drowsiness (1.4% vs. 0.6%).[7] Side effects occurring less than 1% of the time include: blood disorders, impotence, depression, peripheral neuropathy, insomnia, tachycardia, gingival enlargement, hepatitis, and jaundice.[7][32][33]

Amlodipine-associated gingival overgrowth is a relatively common side effect with exposure to amlodipine.[34] Poor dental health and buildup of dental plaque are risk factors.[34]

Amlodipine may increase the risk of worsening angina or acute myocardial infarction, especially in those with severe obstructive coronary artery disease, upon dosage initiation or increase. However, depending on the situation, amlodipine inhibits constriction and restores blood flow in coronary arteries as a result of its acting directly on vascular smooth muscle, causing a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance and a consequent reduction in blood pressure.[10]

Amlodipine and other dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are associated with primary open angle glaucoma.[35]

Overdose

[edit]Although rare,[36] amlodipine overdose toxicity can result in widening of blood vessels, severe low blood pressure, and fast heart rate.[37] Toxicity is generally managed with fluid replacement[38] monitoring ECG results, vital signs, respiratory system function, glucose levels, kidney function, electrolyte levels, and urine output. Vasopressors are also administered when low blood pressure is not alleviated by fluid resuscitation.[7][37]

Interactions

[edit]Several drugs interact with amlodipine to increase its levels in the body. CYP3A inhibitors, by nature of inhibiting the enzyme that metabolizes amlodipine, CYP3A4, are one such class of drugs. Others include the calcium-channel blocker diltiazem, the antibiotic clarithromycin, and possibly some antifungals.[7] Amlodipine causes several drugs to increase in levels, including cyclosporine, simvastatin, and tacrolimus (the increase in the last one being more likely in people with CYP3A5*3 genetic polymorphisms).[39] When more than 20 mg of simvastatin, a lipid-lowering agent, are given with amlodipine, the risk of myopathy increases.[40] The FDA issued a warning to limit simvastatin to a maximum dose of 20 mg if taken with amlodipine based on evidence from the SEARCH trial.[41] Giving amlodipine with Viagra increases the risk of hypotension.[7][10]

Pharmacology

[edit]Amlodipine is a long-acting calcium channel antagonist that selectively inhibits calcium ion influx across cell membranes.[42] It targets L-type calcium channels in muscle cells and N-type calcium channels in the central nervous system which are involved in nociceptive signalling and pain perception.[43][44] Amlodipine has an inhibitory effect on calcium influx in smooth muscle cells to inhibit contraction.[citation needed]

Amlodipine ends up significantly reducing total vascular resistance without decreasing cardiac output expressed by pressure-rate product and cardiac contractability in comparison with verapamil, a non-dihydropyridine.[45] In turn, following treatment lasting a month, with amlodipine, cardiac output is significantly enhanced.[45] Unlike verapamil which has efficacy in moderation of emotional arousal and reduces cardiac load without lowering cardiac output demands, amlodipine increases the cardiac output response concomitantly with increased functional cardiac load.[45]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Amlodipine is an angioselective calcium channel blocker and inhibits the movement of calcium ions into vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiac muscle cells which inhibits the contraction of cardiac muscle and vascular smooth muscle cells. Amlodipine inhibits calcium ion influx across cell membranes, with a greater effect on vascular smooth muscle cells. This causes vasodilation and a reduction in peripheral vascular resistance, thus lowering blood pressure. Its effects on cardiac muscle also prevent excessive constriction in the coronary arteries.[10]

Negative inotropic effects can be detected in vitro, but such effects have not been seen in intact animals at therapeutic doses. Among the two stereoisomers [R(+), S(–)], the (–) isomer has been reported to be more active than the (+) isomer.[46] Serum calcium concentration is not affected by amlodipine. And it specifically inhibits the currents of L-type Cav1.3 channels in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal gland.[47][48]

The mechanisms by which amlodipine relieves angina are:

- Stable angina: amlodipine reduces the total peripheral resistance (afterload) against which the heart works and reduces the rate pressure product, thereby lowering myocardial oxygen demand, at any given level of exercise.[49]

- Variant angina: amlodipine blocks spasm of the coronary arteries and restores blood flow in coronary arteries and arterioles in response to calcium, potassium, epinephrine, serotonin, and thromboxane A2 analog in experimental animal models and in human coronary vessels in vitro.[50]

Amlodipine has additionally been found to act as an antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor, or as an antimineralocorticoid.[51]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Amlodipine has been studied in healthy volunteers following oral administration of 14C-labelled drug.[53] Amlodipine is well absorbed by the oral route with a mean oral bioavailability around 60%; the half-life of amlodipine is about 30 h to 50 h, and steady-state plasma concentrations are achieved after 7 to 8 days of daily dosing.[7] In the blood it has high plasma protein binding of 97.5%.[43] Its long half-life and high bioavailability are largely in part of its high pKa (8.6); it is ionized at physiological pH, and thus can strongly attract proteins.[7] It is slowly metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4, with its amine group being oxidized and its side ester chain being hydrolyzed, resulting in an inactive pyridine metabolite.[54] Renal elimination is the major route of excretion with about 60% of an administered dose recovered in urine, largely as inactive pyridine metabolites. However, renal impairment does not significantly influence amlodipine elimination.[55] 20-25% of the drug is excreted in the faeces.[56]

History

[edit]Pfizer's patent protection on Norvasc lasted until 2007; total patent expiration occurred later in 2007.[57] A number of generic versions are available. In the United Kingdom, tablets of amlodipine from different suppliers may contain different salts. The strength of the tablets is expressed in terms of amlodipine base, i.e., without the salts. Tablets containing different salts are therefore considered interchangeable. A fixed-dose combination of amlodipine and perindopril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor is also available.[58]

The medical form comes as besilate, mesylate, or maleate.[59]

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]In the US, Norvasc is marketed by Viatris after Upjohn was spun off from Pfizer.[60][61]

Veterinary use

[edit]Amlodipine is most often used to treat systemic hypertension in both cats and dogs.[62] In cats, it is the first line of treatment due to its efficacy and few side effects.[63] Systemic hypertension in cats is usually secondary to another abnormality, such as chronic kidney disease, and so amlodipine is most often administered to cats with kidney disease.[64] While amlodipine is used in dogs with systemic hypertension, it is not as efficacious. Amlodipine is also used to treat congestive heart failure due to mitral valve regurgitation in dogs.[65] By decreasing resistance to forward flow in the systemic circulation it results in a decrease in regurgitant flow into the left atrium.[66] Similarly, it can be used on dogs and cats with left-to-right shunting lesions such as ventricular septal defect to reduce the shunt. Side effects are rare in cats. In dogs, the primary side effect is gingival hyperplasia.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ "Medical Definition of Amlodipine". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Amlodipine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 28 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Poisons Standard June 2017". legislation.gov.au. 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Norvasc Product and Consumer Medicine Information Licence". TGA eBS. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Norvasc product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Istin 5 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Norvasc- amlodipine besylate tablet". DailyMed. 14 March 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Norliqva- amlodipine solution". DailyMed. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Amlodipine" (PDF). List of nationally authorised medicinal products. European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Amlodipine Besylate". Drugs.com. American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Boden WE (2012). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 465. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 June 2023. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Amlodipine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Medicines in the health system". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2 July 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Wang JG (2009). "A combined role of calcium channel blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers in stroke prevention". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 5: 593–605. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s6203. PMC 2725792. PMID 19688100.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Stable angina

- ^ a b Chen GJ, Yang MS (6 March 2013). "The effects of calcium channel blockers in the prevention of stroke in adults with hypertension: a meta-analysis of data from 273,543 participants in 31 randomized controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57854. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857854C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057854. PMC 3590278. PMID 23483932.

- ^ a b Mukete BN, Cassidy M, Ferdinand KC, Le Jemtel TH (August 2015). "Long-Term Anti-Hypertensive Therapy and Stroke Prevention: A Meta-Analysis". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 15 (4): 243–257. doi:10.1007/s40256-015-0129-0. PMID 26055616. S2CID 33792903.

- ^ a b Iyengar SS, Mohan JC, Ray S, Rao MS, Khan MY, Patted UR, et al. (December 2021). "Effect of Amlodipine in Stroke and Myocardial infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Cardiology and Therapy. 10 (2): 429–444. doi:10.1007/s40119-021-00239-1. PMC 8555097. PMID 34480745.

- ^ Baumhäkel M, Böhm M (April 2010). "Recent achievements in the management of Raynaud's phenomenon". Vascular Health and Risk Management. 6: 207–214. doi:10.2147/vhrm.s5255. PMC 2856576. PMID 20407628.

- ^ Musa R, Qurie A (2024). "Raynaud Disease". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763008.

- ^ Delgado-Montero A, Zamorano JL (December 2012). "Atorvastatin calcium plus amlodipine for the treatment of hypertension". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (18): 2673–2685. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.742064. PMID 23140185. S2CID 43250258.

- ^ "Amlodipine Disease Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Grimard BH, Safford RE, Burns EL (March 2016). "Aortic Stenosis: Diagnosis and Treatment". American Family Physician. 93 (5): 371–378. PMID 26926974. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017.

- ^ Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2014). The Top 100 Drugs e-book: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 90. ISBN 9780702055157. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Amlodipine: medicine to treat high blood pressure". nhs.uk. 29 August 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Russell RP (March 1988). "Side effects of calcium channel blockers". Hypertension. 11 (3 Pt 2): II42 – II44. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.11.3_Pt_2.II42. PMID 3280492.

- ^ Sica D (1 July 2003). "Calcium channel blocker-related periperal edema: can it be resolved?". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 5 (4): 291–4, 297. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.02402.x. PMC 8099365. PMID 12939574. S2CID 38027134.

- ^ Munoz R, Vetterly CG, Rother SJ, Da Cruz EM (18 October 2007). Handbook of Pediatric Cardiovascular Drugs. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 96. ISBN 9781846289538. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Ono M, Tanaka S, Takeuchi R, Matsumoto H, Okada H, Yamamoto H, et al. (2010). "Prevalence of Amlodipine-induced Gingival Overgrowth". International Journal of Oral-Medical Sciences. 9 (2): 96–100. doi:10.5466/ijoms.9.96.

- ^ a b Gaur S, Agnihotri R (June 2018). "Is dental plaque the only etiological factor in Amlodipine induced gingival overgrowth? A systematic review of evidence". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 10 (6): e610 – e619. doi:10.4317/jced.54715. PMC 6005094. PMID 29930781.

- ^ Kastner A, Stuart KV, Montesano G, De Moraes CG, Kang JH, Wiggs JL, et al. (October 2023). "Calcium Channel Blocker Use and Associated Glaucoma and Related Traits Among UK Biobank Participants". JAMA Ophthalmology. 141 (10): 956–964. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2023.3877. PMC 10485742. PMID 37676684.

- ^ Aronson J (2014). Side Effects of Drugs Annual 35. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-62635-6.

- ^ a b Pillay V (2013). Modern Medical Toxicology (4th ed.). Jaypee. ISBN 978-93-5025-965-8.

- ^ Hui D (2015). Approach to Internal Medicine: A Resource Book for Clinical Practice (4th ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-11820-8.

- ^ Zuo XC, Zhou YN, Zhang BK, Yang GP, Cheng ZN, Yuan H, et al. (2013). "Effect of CYP3A5*3 polymorphism on pharmacokinetic drug interaction between tacrolimus and amlodipine". Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 28 (5): 398–405. doi:10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-12-RG-148. PMID 23438946. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017.

- ^ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (15 December 2017). "FDA Drug Safety Communication: New restrictions, contraindications, and dose limitations for Zocor (simvastatin) to reduce the risk of muscle injury". Drug Safety and Availability. FDA. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Armitage J, Bowman L, Wallendszus K, Bulbulia R, Rahimi K, Haynes R, et al. (November 2010). "Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol with 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial infarction: a double-blind randomised trial". Lancet. 376 (9753): 1658–1669. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60310-8. PMC 2988223. PMID 21067805.

- ^ Ananchenko G, Novakovic J, Lewis J (1 January 2012). "Amlodipine Besylate". Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients, and Related Methodology. Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology. Vol. 37. Academic Press. pp. 31–77. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-397220-0.00002-7. ISBN 9780123972200. PMID 22469316. S2CID 205142025.

- ^ a b "Amlodipine". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Clusin WT, Anderson ME (1 January 1999). Calcium Channel Blockers: Current Controversies and Basic Mechanisms of Action. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 46. Academic Press. pp. 253–296. doi:10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60473-1. ISBN 9780120329472. PMID 10332505.

- ^ a b c Nazzaro P, Manzari M, Merlo M, Triggiani R, Scarano AM, Lasciarrea A, et al. (September 1995). "Antihypertensive treatment with verapamil and amlodipine. Their effect on the functional autonomic and cardiovascular stress responses". European Heart Journal. 16 (9): 1277–1284. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061086. PMID 8582392.

- ^ Karmoker JR, Joydhar P, Sarkar S, Rahman M (2016). "Comparative in vitro evaluation of various commercial brands of amlodipine besylate tablets marketed in Bangladesh" (PDF). Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Health Sciences. 6: 1384–1389. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ Arcangelo VP, Peterson AM (2006). Pharmacotherapeutics for Advanced Practice: A Practical Approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781757843. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Ritter J, Lewis L, Mant T, Ferro A (2012). A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (5 ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781444113006. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Li YR (2015). Cardiovascular Diseases: From Molecular Pharmacology to Evidence-Based Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470915370. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ 2013 Nurse's Drug Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2012. ISBN 9781449642846. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Luther JM (September 2014). "Is there a new dawn for selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism?". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 23 (5): 456–461. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000051. PMC 4248353. PMID 24992570.

- ^ Zhu Y, Wang F, Li Q, Zhu M, Du A, Tang W, et al. (February 2014). "Amlodipine metabolism in human liver microsomes and roles of CYP3A4/5 in the dihydropyridine dehydrogenation". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 42 (2): 245–249. doi:10.1124/dmd.113.055400. PMID 24301608. S2CID 329321.

- ^ Beresford AP, McGibney D, Humphrey MJ, Macrae PV, Stopher DA (February 1988). "Metabolism and kinetics of amlodipine in man". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems. 18 (2): 245–254. doi:10.3109/00498258809041660. PMID 2967593.

- ^ Nayler WG (2012). Amlodipine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 105. ISBN 9783642782237. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Brittain HG (2012). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123977564. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Murdoch D, Heel RC (March 1991). "Amlodipine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in cardiovascular disease". Drugs. 41 (3): 478–505. doi:10.2165/00003495-199141030-00009. PMID 1711448. S2CID 195693179.

- ^ Kennedy VB (22 March 2007). "Pfizer loses court ruling on Norvasc patent". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008.

- ^ Multum Consumer Information on amlodipine and perindopril. Accessed 28 February 2020.

- ^ Campbell AK (14 October 2014). Intracellular Calcium. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 9781118675526. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Pfizer Completes Transaction to Combine Its Upjohn Business with Mylan". Pfizer. 16 November 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Norvasc". Pfizer. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Papich MG (2007). "Amlodipine Besylate". Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9781416028888.

- ^ Henik RA, Snyder PS, Volk LM (28 August 2014). "Treatment of systemic hypertension in cats with amlodipine besylate". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 33 (3): 226–234. doi:10.5326/15473317-33-3-226. PMID 9138233.

- ^ "Amlodipine in Veterinary Medicine". Diamondback Drugs. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Atkins C, Bonagura J, Ettinger S, Fox P, Gordon S, Haggstrom J, et al. (1 November 2009). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease" (PDF). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 23 (6): 1142–1150. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0392.x. PMID 19780929. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Suzuki S, Fukushima R, Ishikawa T, Yamamoto Y, Hamabe L, Kim S, et al. (September 2012). "Comparative effects of amlodipine and benazepril on left atrial pressure in dogs with experimentally-induced mitral valve regurgitation". BMC Veterinary Research. 8: 166. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-8-166. PMC 3489586. PMID 22989022.

- ^ Forney B. "Amlodipine for Veterinary Use". Wedgewood Pharmacy. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.