Caryatid

A caryatid (/ˌkɛəriˈætɪd, ˌkær-/ KAIR-ee-AT-id, KARR-;[1] Ancient Greek: Καρυᾶτις, romanized: Karuâtis; pl. Καρυάτιδες, Karuátides)[2] is a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a column or a pillar supporting an entablature on her head. The Greek term karyatides literally means "maidens of Karyai", an ancient town on the Peloponnese. Karyai had a temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis in her aspect of Artemis Karyatis: "As Karyatis she rejoiced in the dances of the nut-tree village of Karyai, those Karyatides, who in their ecstatic round-dance carried on their heads baskets of live reeds, as if they were dancing plants".[3]

An atlas or atlantid or telamon is a male version of a caryatid, i.e., a sculpted male statue serving as an architectural support.

Etymology

[edit]The term is first recorded in the Latin form caryatides by the Roman architect Vitruvius. He stated in his 1st century BC work De architectura (I.1.5) that certain female figures represented the punishment of the women of Caryae, a town near Sparta in Laconia, who were condemned to slavery after betraying Athens by siding with Persia in the Greco-Persian Wars. However, Vitruvius's explanation is doubtful; well before the Persian Wars, female figures were used as decorative supports in Greece[4] and the ancient Near East. Vitruvius's explanation is dismissed as an error by Camille Paglia in Glittering Images and not even mentioned by Mary Lefkowitz in Black Athena Revisited.[5][6] They both say the term refers to young women worshipping Artemis in Caryae through dance. Lefkowitz says that the term comes from the Spartan city of Caryae, where young women did a ring dance around an open-air statue of the goddess Artemis, locally identified with a walnut tree. Bernard Sergent specifies that the dancers came to the small town of Caryae from nearby Sparta.[7] Nevertheless, the association of caryatids with slavery persists and is prevalent in Renaissance art.[8]

The ancient Caryae supposedly was one of the six adjacent villages that united to form the original township of Sparta, and the hometown of Menelaos' queen, Helen of Troy. Girls from Caryae were considered especially beautiful, strong, and capable of giving birth to strong children.[citation needed]

A caryatid supporting a basket on her head is called a canephora ("basket-bearer"), representing one of the maidens who carried sacred objects used at feasts of the goddesses Athena and Artemis. The Erectheion caryatids, in a shrine dedicated to an archaic king of Athens, may therefore represent priestesses of Artemis in Caryae, a place named for the "nut-tree sisterhood" – apparently in Mycenaean times, like other plural feminine toponyms, such as Hyrai or Athens itself.

The later male counterpart of the caryatid is referred to as a telamon (plural telamones) or atlas (plural atlantes) – the name refers to the legend of Atlas, who bore the sphere of the heavens on his shoulders. Such figures were used on a monumental scale, notably in the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Agrigento, Sicily.

Ancient usage

[edit]

Some of the earliest known examples were found in the treasuries of Delphi, including that of Siphnos, dating to the 6th century BC. However, their use as supports in the form of women can be traced back even earlier, to ritual basins, ivory mirror handles from Phoenicia, and draped figures from archaic Greece.

The best-known and most-copied examples are those of the six figures of the Caryatid porch of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis at Athens. One of those original six figures, removed by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century in an act which severely damaged the temple and is widely considered to be vandalism and looting, is currently in the British Museum in London. The Greek government does not recognise the British Museum's claims to own any part of the Acropolis temples and the return of the stolen Caryatid to Athens along with the rest of the so-called Elgin Marbles is the subject of a major international campaign. The Acropolis Museum holds the other five figures, which are replaced onsite by replicas. The five originals that are in Athens are now being exhibited in the new Acropolis Museum, on a special balcony that allows visitors to view them from all sides. The pedestal for the caryatid removed to London remains empty, awaiting its return. From 2011 to 2015, they were cleaned by a specially constructed laser beam, which removed accumulated soot and grime without harming the marble's patina. Each caryatid was cleaned in place, with a television circuit relaying the spectacle live to museum visitors.[9]

Although of the same height and build, and similarly attired and coiffed, the six Caryatids are not the same: their faces, stance, draping, and hair are carved separately; the three on the left stand on their right foot, while the three on the right stand on their left foot. Their bulky, intricately arranged hairstyles serve the crucial purpose of providing static support to their necks, which would otherwise be the thinnest and structurally weakest part.

The Romans also copied the Erechtheion caryatids, installing copies in the Forum of Augustus and the Pantheon in Rome, and at Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli. Another Roman example, found on the Via Appia, is the Townley Caryatid.[10]

Renaissance and after

[edit]In Early Modern times, the practice of integrating caryatids into building facades was revived, and in interiors they began to be employed in fireplaces, which had not been a feature of buildings in Antiquity and offered no precedents. Early interior examples are the figures of Heracles and Iole carved on the jambs of a monumental fireplace in the Sala della Jole of the Doge's Palace, Venice, about 1450.[11] In the following century Jacopo Sansovino, both sculptor and architect, carved a pair of female figures supporting the shelf of a marble chimneypiece at Villa Garzoni, near Padua.[12] No architect mentioned the device until 1615, when Palladio's pupil Vincenzo Scamozzi included a chapter devoted to chimneypieces in his Idea della archittura universale. Those in the apartments of princes and important personages, he considered, might be grand enough for chimneypieces with caryatid supporters, such as one he illustrated and a similar one he installed in the Sala dell'Anticollegio, also in the Doge's Palace.[13]

In the 16th century, from the examples engraved for Sebastiano Serlio's treatise on architecture, caryatids became a fixture in the decorative vocabulary of Northern Mannerism expressed by the Fontainebleau School and the engravers of designs in Antwerp. In the early 17th century, interior examples appear in Jacobean interiors in England; in Scotland the overmantel in the great hall of Muchalls Castle remains an early example. Caryatids remained part of the German Baroque vocabulary and were refashioned in more restrained and "Grecian" forms by neoclassical architects and designers, such as the four terracotta caryatids on the porch of St Pancras New Church, London (1822).

Many caryatids lined up on the facade of the 1893 Palace of the Arts housing the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. In the arts of design, the draped figure supporting an acanthus-grown basket capital taking the form of a candlestick or a table-support is a familiar cliché of neoclassical decorative arts. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota has caryatids as a motif on its eastern facade.

In 1905 American sculptor Augustus Saint Gaudens created a caryatid porch for the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York in which four of the eight figures (the other four figures holding only wreaths) represented a different art form, Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, and Music.[14]

Auguste Rodin's 1881 sculpture Fallen Caryatid Carrying her Stone (part of his monumental The Gates of Hell work)[15] shows a fallen caryatid. Robert Heinlein described this piece in Stranger in a Strange Land: "Now here we have another emotional symbol... for almost three thousand years or longer, architects have designed buildings with columns shaped as female figures... After all those centuries it took Rodin to see that this was work too heavy for a girl... Here is this poor little caryatid who has tried—and failed, fallen under the load.... She didn't give up, Ben; she's still trying to lift that stone after it has crushed her..."[16]

In Act 2 of his 1953 play 'Waiting for Godot', author Samuel Beckett has Estragon say "We are not caryatids!" when he and Vladimir tire of "cart(ing) around" the recently blinded Pozzo.

Agnes Varda made two short films documenting Caryatid columns around Paris. 1984 Les Dites Cariatides 2005 Les Dites Cariatides Bis.

The musical group Son Volt evoke the caryatides and their burden borne in poetic metaphor on the song "Caryatid Easy" from their 1997 album Straightaways, with singer Jay Farrar reproving an unidentified lover with the line "you play the caryatid easy."

Gallery

[edit]-

Ancient Greek caryatids of the Cnidian Treasury, c.550 BC, probably marble, Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi, Greece

-

Ancient Greek mirror, 5th century BC, bronze, Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth, Corinth, Greece

-

Ancient Greek caryatids of the Erechtheion, Greece, unknown architect, 421-405 BC[17]

-

Roman caryatid from the Sanctuary of Demeter at Eleusis, second half of 1st century BC, probably marble, Archaeological Museum of Eleusis, Elefsina, Greece

-

Las Incantadas, a group of Roman sculptures from a portico that once adorned the Roman Forum of Thessalonica, 150-230 AD, marble, Louvre[18]

-

Renaissance caryatids on the Cassetta Farnese, by Manno Sbarri, Giovanni Bernardi and Perin del Vaga, 1548-1561, gilded silver, embossed and chiselled rock crystal, enamel and lapis lazuli, Louvre

-

Baroque caryatids on the upper part of the Pavillon de l'Horloge on the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, by Gilles Guérin and Philippe De Buyster after Jacques Sarazin, mid 17th century[21]

-

Baroque caryatids of a cabinet, c.1675, ebony, kingwood, marquetry of hard stones, gilt bronze, pewter, glass, tinted mirror and horn, Museum of Decorative Art, Strasbourg, France[22]

-

Baroque caryatids in the Apollo and Attendants Flaying Marsyas tapestry, 17th century, wool and silk, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, US

-

Louis XVI style jewelry locket of Marie-Antoinette, by Ferdinand Schwerdfeger, 1787, mahogany, mother-of-pearl inlays, paintings under glass, porcelain plate, and gilded bronzes, Chambre de la Reine, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France[23]

-

Pair of Louis XVI style caryatid, 18th century, gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Louis XVI style caryatids on the Médicis Vase, by Louis-Simon Boizot, Pierre Philippe-Thomire and the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, c.1787, porcelain and gilded bronze, Louvre[24]

-

Neoclassical caryatids of the portal of the Palais Pallavicini in Josefsplatz, Vienna, Austria, by Johann Ferdinand Hetzendorf von Hohenberg, 1784

-

Empire style table with caryatids en gaine supported by bare feet, early 19th century, wood, metal, glass, pigment, and porcelain, Musée Dufresne-Nincheri, Montreal, Canada

-

Neoclassical porch with caryatids of the St Pancras New Church, London, almost identical with the Ancient Greek one of the Erechtheum, by William and Henry William Inwood, 1819-1822

-

Polychrome Greek Revival caryatids of the Walhalla Temple, near Regensburg, Germany, designed by Leo von Klenze in 1821, built in 1830-1842[25]

-

Neoclassical caryatids of the Winkel van Sinkel department store, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 1837-1839, by P. Adams[26]

-

Neoclassical caryatids of the south wall of the Room of the Niobids, Neues Museum, Berlin, by Friedrich August Stüler, 1845-1850[28]

-

Neoclassical caryatids of Quai de la Mégisserie no. 14, Paris, sculptor Auguste Millet and architect Henri Blondel, 1864[29]

-

Renaissance Revival caryatids on the Jenners, department store, Edinburgh, UK, by William Hamilton Beattie, 1894

-

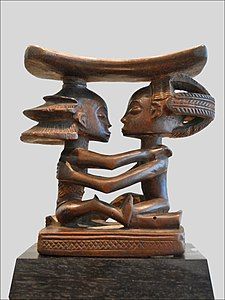

Luba headrest with two caryatid, 19th century, wood, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

-

Luba stool with two caryatids, 19th century, wood, Ethnological Museum of Berlin

-

Rococo Revival gilt bronze caryatid on the fireplace in the room 538 of the Louvre Palace, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, 19th century

-

Pair of Neoclassical caryatids at the entrance of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (Rue Saint-Martin no. 292), Paris, unknown architect, mid-19th century

-

Neoclassical caryatids of Rue des Halles no. 19, Paris, designed by Jean Lobrot and sculpted by Charles Gauthier, 1868

-

Double Beaux Arts caryatid on the façade of the Théâtre de la Renaissance, Paris, by Charles de Lalande, 1873

-

Beaux Arts caryatid (mainly Neoclassical, but also Baroque Revival through the lower part rotated at 45°) of Rue Chomel no. 11, Paris, by J. Vramant, 1878-1880

-

Neoclassical caryatids of a Wallace fountain in Place Moussa-et-Odette-Abadi, Paris, designed by Richard Wallace and produced by Charles-Auguste Lebourg, late 19th century

-

Art Nouveau caryatid-corbel on the Maison Vallin (Boulevard Lobau no. 6), Nancy, France, 1894, by Eugène Vallin[30]

-

Beaux Arts caryatids of a oriel window of Strada Buzești no. 4, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1900

-

Beaux Arts atlas and caryatid of Avenue de Tourvill no. 4, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1900

-

Beaux Arts mermaid caryatids with a cartouche in Le Train Bleu, Gare de Lyon, Paris, 1901, by Marius Toudoire

-

Rococo Revival caryatids of Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs no. 82, Paris, designed by Constant Lemaire and sculpted by Louis Hollweck, 1904-1905

-

Art Deco caryatids on Banca Albina (Strada Edgar Quinet no. 6), Bucharest, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1930

-

Art Deco caryatids of the Monument to the Unknown Hero, atop Mount Avala, south-east of Belgrade, Serbia, wirhcaryatids representing all the peoples of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, by Ivan Meštrović, 1934–1938[31]

-

Neoclassical caryatids of the Alley of Caryatids in the Herăstrău Park, Bucharest, dressed like Romanian peasant women, sculpted by Constantin Ricci, 1939[32]

-

Postmodern Venus de Milo caryatids of Rue Frank Lloyd Wright no. 14, Guyancourt, France, by Manuel Núñez Yanowsky, 1992

-

Postmodern caryatids of the Supreme Court of Poland, Warsaw, by Marek Budzynski and Zbigniew Badowski, 1996-1999

-

Postmodern cast stone caryatids in Nogales, Mexico, unknown architect, unknown date

-

Caryatides, ca. 1865; from the Nicholas Catsimpoolas Collection of the Boston Public Library

See also

[edit]- Caryatid stools in African art

- Term (architecture)

- The Sphere: Große Kugelkaryatide (Great Spherical Caryatid) – WTC sculpture by Fritz Koenig

References

[edit]- ^ "caryatid". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Καρυᾶτις in Bailly, Anatole (1935) Le Grand Bailly: Dictionnaire grec-français, Paris: Hachette

- ^ (Kerenyi 1980 p 149)

- ^ Hersey, George, The Lost Meaning of Classical Architecture, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1998 p. 69

- ^ Glittering Images, p. 25

- ^ Black Athena Revisited, p. 197

- ^ caryatide in "Notre grec de tous les jours" by Bernard Sergent

- ^ The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophies to Abolitionist Emblem, ed Elizabeth Mcgrath and Jean Michel Massing, London (The Warburg Institute) 2012

- ^ Alderman, Liz (7 July 2014). "Acropolis Maidens Glow Anew". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ A. H. Smith, "Gavin Hamilton's Letters to Charles Townley" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 21 (1901: 306–321) p. 306 note 3. Townley inventories, where it is interpolated between No. 9 (Hecate) and No. 10 (Fortune).

- ^ Noted by James Parker, in describing the precedents for the white marble caryatid chimneypiece from Chesterfield House, Westminster, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Parker, "'Designed in the Most Elegant Manner, and Wrought in the Best Marbles': The Caryatid Chimney Piece from Chesterfield House", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, 21.6 [February 1963] pp. 202–213).

- ^ Also noted by Parker 1963:206.

- ^ Both remarked upon by Parker 1963:206, and fig. 9.

- ^ "archsculptbooks.com". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Fallen Caryatid Carrying Her Stone". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (1961). Stranger in a Strange Land. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-441-79034-0.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ "L'Incantada". collections.louvre.fr. April 0150. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Pinelli, Antonio (2010). Souvenir (in Italian). Laterza. p. 93. ISBN 978-88-420-9417-3.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- ^ "Cabinet parisien 17e siècle". musees-strasbourg.skin-web.org. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Serre-bijoux de Marie-Antoinette". 1774. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Vase Médicis". collections.louvre.fr. 1774. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 486. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ "Winkel van Sinkel". openmonumentendag.nl. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Maison en terre cuite de Virebent". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Bertram, Marion (2020). Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection; Museum of Prehistory and Early History. Prestel. p. 118. ISBN 978-3-7913-4262-7.

- ^ "Immeuble". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Immeuble". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "СПОМЕНИК НЕЗНАНОМ ЈУНАКУ НА АВАЛИ (Monument to the Unknown Hero on Avala)". Monuments of Culture of Serbia (in Serbian). National Center for Digitization. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Mariana Celac, Octavian Carabela and Marius Marcu-Lapadat (2017). Bucharest Architecture - an annotated guide. Ordinul Arhitecților din România. p. 149. ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

External links

[edit]- Kerényi, Karl (1951) 1980. The Gods of the Greeks (Thames & Hudson)

- Conserving the Caryatids in the Acropolis Museum

- Images of Caryatids of Athens (Spanish)

- Cariatides room of the Louvre on YouTube

![Ancient Greek caryatids of the Erechtheion, Greece, unknown architect, 421-405 BC[17]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Athen_Erechtheion_BW_2017-10-09_13-58-34.jpg/442px-Athen_Erechtheion_BW_2017-10-09_13-58-34.jpg?auto=webp)

![Las Incantadas, a group of Roman sculptures from a portico that once adorned the Roman Forum of Thessalonica, 150-230 AD, marble, Louvre[18]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Las_Incantadas_%28Louvre%29_3.jpg/225px-Las_Incantadas_%28Louvre%29_3.jpg?auto=webp)

![Townley Caryatid, 161-171, Pentelic marble, British Museum, London[19]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Townley_Caryatid_-_British_Museum_-_Joy_of_Museums.jpg/163px-Townley_Caryatid_-_British_Museum_-_Joy_of_Museums.jpg?auto=webp)

![Renaissance caryatids of the musicians' loft in the Louvre Palace, Paris, by Jean Goujon, 1550[20]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Paris_Palais_du_Louvre_Salle_des_Caryatides_tribune_20161031.jpg/225px-Paris_Palais_du_Louvre_Salle_des_Caryatides_tribune_20161031.jpg?auto=webp)

![Baroque caryatids on the upper part of the Pavillon de l'Horloge on the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, by Gilles Guérin and Philippe De Buyster after Jacques Sarazin, mid 17th century[21]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Facade_Pavillon_Horloge_Louvre.jpg/198px-Facade_Pavillon_Horloge_Louvre.jpg?auto=webp)

![Baroque caryatids of a cabinet, c.1675, ebony, kingwood, marquetry of hard stones, gilt bronze, pewter, glass, tinted mirror and horn, Museum of Decorative Art, Strasbourg, France[22]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Antichambre_du_prince-%C3%A9v%C3%AAque_%28Palais_Rohan%2C_Strasbourg%29_cabinet.JPG/200px-Antichambre_du_prince-%C3%A9v%C3%AAque_%28Palais_Rohan%2C_Strasbourg%29_cabinet.JPG?auto=webp)

![Louis XVI style jewelry locket of Marie-Antoinette, by Ferdinand Schwerdfeger, 1787, mahogany, mother-of-pearl inlays, paintings under glass, porcelain plate, and gilded bronzes, Chambre de la Reine, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France[23]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/P1030075_%285015797888%29.jpg/400px-P1030075_%285015797888%29.jpg?auto=webp)

![Louis XVI style caryatids on the Médicis Vase, by Louis-Simon Boizot, Pierre Philippe-Thomire and the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, c.1787, porcelain and gilded bronze, Louvre[24]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Vase_Medicis_%28Louvre%2C_OA_9590%29.jpg/225px-Vase_Medicis_%28Louvre%2C_OA_9590%29.jpg?auto=webp)

![Polychrome Greek Revival caryatids of the Walhalla Temple, near Regensburg, Germany, designed by Leo von Klenze in 1821, built in 1830-1842[25]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Walhalla_Halle1.jpg/423px-Walhalla_Halle1.jpg?auto=webp)

![Neoclassical caryatids of the Winkel van Sinkel department store, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 1837-1839, by P. Adams[26]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Kariatiden_Winkel_van_Sinkel.JPG/225px-Kariatiden_Winkel_van_Sinkel.JPG?auto=webp)

![Neoclassical white terracotta caryatids of the Virebent Factory, Toulouse, France, by Auguste Virebent, 1840[27]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Immeuble-cariatides_%282%29.jpg/459px-Immeuble-cariatides_%282%29.jpg?auto=webp)

![Neoclassical caryatids of the south wall of the Room of the Niobids, Neues Museum, Berlin, by Friedrich August Stüler, 1845-1850[28]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/South_wall_of_the_Room_of_the_Niobids%2C_Neues_Museum%2C_Berlin.jpg/184px-South_wall_of_the_Room_of_the_Niobids%2C_Neues_Museum%2C_Berlin.jpg?auto=webp)

![Neoclassical caryatids of Quai de la Mégisserie no. 14, Paris, sculptor Auguste Millet and architect Henri Blondel, 1864[29]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Paris_Quai_de_la_M%C3%A9gisserie_543.jpg/200px-Paris_Quai_de_la_M%C3%A9gisserie_543.jpg?auto=webp)

![Art Nouveau caryatid-corbel on the Maison Vallin (Boulevard Lobau no. 6), Nancy, France, 1894, by Eugène Vallin[30]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/80/D%C3%A9tail_de_la_fa%C3%A7ade_06939_%28cropped_caryatid%29.jpg/239px-D%C3%A9tail_de_la_fa%C3%A7ade_06939_%28cropped_caryatid%29.jpg?auto=webp)

![Art Deco caryatids of the Monument to the Unknown Hero, atop Mount Avala, south-east of Belgrade, Serbia, wirhcaryatids representing all the peoples of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, by Ivan Meštrović, 1934–1938[31]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Spomenik_Neznanom_junaku_1.JPG/400px-Spomenik_Neznanom_junaku_1.JPG?auto=webp)

![Neoclassical caryatids of the Alley of Caryatids in the Herăstrău Park, Bucharest, dressed like Romanian peasant women, sculpted by Constantin Ricci, 1939[32]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/Aleea_Cariatidelor_de_Constantin_Baraschi.jpg/520px-Aleea_Cariatidelor_de_Constantin_Baraschi.jpg?auto=webp)