Acjachemen

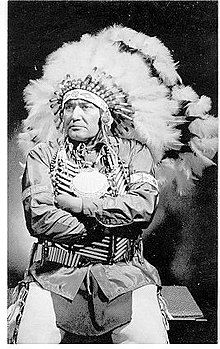

José de Grácia Cruz, an Acjachemen craftsman and bell ringer at Mission San Juan Capistrano, photo taken ca. June 1909. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| about 1,900[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (California) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, formerly Juaneño | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Payómkawichum (Luiseño), Tongva (Gabrieleño) |

The Acjachemen (/ɑːˈxɑːtʃəməm/) are an Indigenous people of California. Published maps often identify their ancestral lands as extending from the beach to the mountains, south from what is now known as Aliso Creek in Orange County to the Las Pulgas Canyon in the northwestern part of San Diego County.[2] However, sources also show that Acjachemen people shared sites with other Indigenous nations as far north as Puvunga in contemporary Long Beach.[3]

The Acjachemen language does not have any fluent speakers. It is closely related to the Luiseño language still spoken by the neighboring Payómkawichum (Luiseño) people.

Name

[edit]Spanish colonists called the Acjachemen Juaneños, following their conversion to Christianity at Mission San Juan Capistrano in the late 18th century.[4] Today, many contemporary members of organizations for Acjachemen descendants prefer the term Acjachemen as their autonym, or name for themselves. The name is derived from the village of Acjacheme, which was less than 60 yards from the site where Mission San Juan Capistrano was built in 1776.[5][6] Alternate spellings include Acachme or Acagchemem.[7]

History

[edit]Pre-colonization

[edit]

Acjachemen creation and origins stories represent their history in Southern California as beginning in the beginning of time. Archaeologists argue there has been an Acjachemen presence in the region for at least 10,000 years.[8]

In the era preceding colonization by Spain, the Acjachemen resided in permanent, well-defined villages and seasonal camps. Village populations ranged from between 35 and 300 residents, consisting of a single lineage in the smaller villages, and of a dominant clan joined with other families in the larger settlements. Each clan had its own resource territory and was politically independent; ties to other villages were maintained through economic, religious, and social networks in the immediate region. The elite class (composed chiefly of families, lineage heads, and other ceremonial specialists), a middle class (established and successful families), and people of disconnected or wandering families and captives of war comprised the three hierarchical social classes.[9]

Native leadership consisted of the Nota, or clan chief, who conducted community rites and regulated ceremonial life in conjunction with the council of elders (puuplem), which was made up of lineage heads and ceremonial specialists in their own right. This body decided upon matters of the community, which were then carried out by the Nota and his underlings. While the placement of residential huts in a village was not regulated, the ceremonial enclosure (vanquesh) and the chief's home were most often centrally located.[10]

The Acjachemen relied upon harvesting and processing acorns, grasses, seeds, and bay shellfish. They had a dietary preference for birds and small mammals like rabbits.[11] They crafted animal bones into weapons, tools, and jewelry.[11]

Mission period

[edit]

A set of highly important Acjachemen villages (Acjachema, Suvit, and Putuidem) were concentrated along the lower San Juan Creek.[12] In 1775, Spanish colonists erected a cross on an Acjachemen religious site before retreating to San Diego due to a revolt at Mission San Diego. They returned one year later to begin constructing and converting the Acjachemen population. The majority of early converts were often children, who may have been brought by their parents in an attempt to "make alliances with missionaries, who not only possessed new knowledge and goods but also presented the threat of force." Spanish military presence ensured the continuation of the mission system.

In 1776, as Junípero Serra approached Acjachemen territory with a Spanish soldier and one "neophyte," a recently baptized Native and Spanish translator, a "crowd of painted and well-armed [Acjachemen] Indians, some of whom put arrows to their bowstrings as though they intended to kill the Spanish intruders" surrounded Serra's group. The "neophyte" informed the Acjachemen that attacking would only result in further violence from the Spanish military. As a result, the Acjachemen "desisted, aware of the serious threat that military retaliation represented."[13]

While, before 1783, those who had been converted, known as "Juaneños, both children and adults, represented a relatively small percentage of the Acjachemen population, all that changed between 1790 and 1812, when the vast majority of remaining non-converts were baptized."[4] Spanish colonists referred to the Acjachemen as Juaneño.[14] The Acjachemen were designated as Juaneños by Spanish priests through the baptismal process performed at Mission San Juan Capistrano, named after St. Juan Capistrano in Spain. Many other local tribes were named similarly (Kizh (pronounced keech) – Gabrieleño; named after Mission San Gabriel).[a]

During the late 18th century, the mission economy extended over the entire territory of the Acjachemen. Acjachemen villages still had "access to specific hunting, collecting, and fishing areas" and "within these collectively owned areas villagers also possessed private property." However, the Indigenous land tenure system was first paralleled and then undermined by the mission system and colonization. The Spanish transformed the countryside into grazing lands for livestock and horticulture. Between 1790 and 1804, "mission herds increased in size from 8,034 head to 26,814 head."[15]

As European disease also began to decimate the rural population, the dominion and power of the Spanish missions over the Acjachemen further increased."[4] By 1812, the mission was at the peak of its growth: "3,340 persons had been baptized at the mission, and 1,361 Acjachemen resided in the mission compound." After 1812, the rate of Acjachemen who died surpassed the amount of those who were baptized. By 1834, the Acjachemen population had declined to about 800.[4]

The Acjachemen resisted assimilation by practicing their cultural and religious ceremonies, performing sacred dances and healing rituals both in villages and within the mission compound. Missionaries attempted to prevent "Indigenous forms of knowledge, authority, and power" from passing on to younger generations by placing recently baptized Indian children in monjerios "away from their parents from the age of seven or so until their marriage." Native children and adults were punished for disobeying Spanish priests through confinement and lashings. The logic behind these harsh practices was "integral to Catholic belief and practice." Gerónimo Boscana, a missionary at San Juan between 1812 and 1822, admitted that, despite harsh treatment, attempts to convert Native people to Christian beliefs and traditions were largely unsuccessful: "All the missionaries in California, declares Boscana, would agree that the true believer was the rare exception."[16]

Emancipation from San Juan mission and Mexican rule

[edit]

Governor José María de Echeandía, the first Mexican governor of Alta California, issued a "Proclamation of Emancipation" (or "Prevenciónes de Emancipacion") on July 25, 1826, which freed Native people from San Diego Mission, Santa Barbara, and Monterey. When news of this spread to other missions, it inspired widespread resistance to work and even open revolt. At San Juan, "the missionary stated that if the 956 neophytes residing at the mission in 1827 were 'kindly begged to go to work,' they would respond by saying simply that they were 'free.'" Following the Mexican secularization act of 1833, "neophyte alcades requested that the community be granted the land surrounding the mission, which the Acjachemen had irrigated and were now using to support themselves."

Terrestrial and marine fauna refuse, food storage vessels, specialized craft goods, ritual artifacts culturally associated with elite clan lineages, and interregional trade connections were found at the Puhú village site.[11]

However, while Acjachemen "claimed and were granted villages," there was "rarely" any legal title issued, meaning that the land was "never formally ceded" to them following emancipation, which they protested as others encroached upon their traditional territory. While rancho grants issued by the Mexican government on the lands of the San Juan mission "were made in the early 1840s, Indians' rights to their village lands went unrecognized." Although the Acjachemen were now "free," they were "increasingly vulnerable to being forced to work on public projects" if it was determined that they had "'reverted' to a state of dependence on wild fruits or neglected planting crops and herding" or otherwise failed to continue practicing Spanish-imposed methods of animal husbandry and horticulture.[17] Because of a lack of formal recognition, "most of the former Acagchemem territory was incorporated into Californio ranchos by 1841, when San Juan Mission was formed into a pueblo."[18]

The formation of the San Juan pueblo was a direct result of the actions of San Diego settlers, who petitioned the government to gain access to the lands of the mission territory. Before the formation of the pueblo, the "one-hundred or so Acjachemen living there" were asked if they favored or opposed this change: seventy voted in favor, while thirty, mostly older, Acjachemen opposed, "possibly because they did not want to live among the Californios." The formation of the San Juan pueblo granted Californios and Acjachemen families solars, or lots for houses, and suertes, or plots of land in which to plant crops.[19]

American occupation, genocide, and territorial conquest

[edit]

Following the American occupation of California in 1846 and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, "Indian peoples throughout California were drawn into the 'cycles of conquest' that had been initiated by the Spanish." During the 1850s alone, the California Indian population declined by 80 percent. Any land rights Native people had under Mexican rule were completely erased under American occupation, as stated in Article 11 of the treaty: "A great part of the territories which, by the present treaty, are to be comprehended for the future within the limits of the United States, is now occupied by savage tribes." As the United States government declared its right to police and control Native people, the "claims of Indians who had acquired land in the 1841 formation" of the San Juan pueblo, "were similarly ignored, despite evidence that the [American] land commission had data substantiating these Juaneños' titles."[21]

By 1860, Acjachemen were recorded in the census "with Spanish first names and no surnames; the occupations of 38 percent of their household heads went unrecorded; and they owned only 1 percent of the land and 0.6 percent of the assets (including cattle, household items, and silver or gold)." It was recorded that 30 percent of all households were headed by women "who still lived in San Juan on the plots of land that had been distributed in 1841" under Mexican rule. It was reported that "shortly after the census was taken, the entire population began to leave the area for villages to the southeast of San Juan." A smallpox epidemic in 1862 took the lives of 129 Acjachemen people in one month alone of a population now "of only some 227 Indians." The remaining Acjachemen established themselves among the Luiseño, who they "shared linguistic and cultural similarities, family ties, and colonial histories." Even after their relocation to various Luiseño villages, "San Juan remained an important town for Acjachemen and other Indians connected to it" so that by the "latter part of the nineteenth century individuals and families often moved back and forth between these villages and San Juan for work, residence, family events, and festivals."[22]

American occupation resulted in increasing power and wealth for European immigrants and Anglo-Americans to own land and property by the 1860s, "in sharp contrast to the pattern among Californios, Mexicans, and Indians." In the Santa Ana and San Juan Capistrano townships, most Californios lost their ranchos in the 1860s. By 1870, European immigrants and Anglo-Americans now owned 87 percent of the land value and 86 percent of the assets. Native people went from owning 1 percent of the land value and assets, as recorded in the 1860 census, to 0 percent in 1870. Anglo-Americans became the majority of the population by the mid-1870s, and the towns in which they resided "were characterized by a marked lack of ethnic diversity."[23] In the 1890s, a permanent elementary school was constructed in San Juan. However, until 1920, for education beyond sixth grade, "students had to relocate to Santa Ana – an impossibility for the vast majority of Californio and Acjachemen families."[24]

Religion

[edit]Gerónimo Boscana, a Franciscan scholar who was stationed at San Juan Capistrano for more than a decade beginning in 1812, compiled the first, comprehensive study of Acjachemen religious practices. Religious knowledge was secret, and the prevalent religion, called Chinigchinich, placed village chiefs in the position of religious leaders, an arrangement that gave the chiefs broad power over their people.[25] Boscana divided the Acjachemen into two classes: the "Playanos" (who lived along the coast) and the "Serranos" (who inhabited the mountains, some three to four leagues from the Mission).[26] The religious beliefs of the two groups as related to creation differed quite profoundly. The Playanos held that an all-powerful and unseen being called "Nocuma" brought about the earth and the sea, together with all of the trees, plants, and animals of sky, land, and water contained therein.[27] The Serranos, on the other hand, believed in two separate but related existences: the "existence above" and the "existence below". These states of being were "altogether explicable and indefinite" (like brother and sister), and it was the fruits of the union of these two entities that created "...the rocks and sands of the earth; then trees, shrubbery, herbs and grass; then animals...".[28] The "Starman" drawn by artist Jean Goodwin has become an iconic image with the Acjachemen people and is seen often in art and tribal seals.[29]

Language

[edit]The Acjachemen language is related to the Luiseño language spoken by the nearby Luiseño tribe located to the interior.[30] Considered to speak a dialect of Luiseño, the Juaneño were part of the Takic subgroup of the northern groupings of the Uto-Aztecan languages. Northern Uto-Aztecan (NUA) is divided into Numic, Tubatrlabalic, Takic, and Hopic. Takic includes seven languages: Kitanemuk, Serrano (including Vanyume), Gabrielino (including Fernandeńo), Luiseño (including Acjachemen), Cahuilla, Cupeño, and Tataviam.[31]

The last fluent speakers of Acjachemen died by the early 20th century. Acjachemen continue working to revive it, and several members are learning it and can speak and sing in the language. Their studies are partly based on the research and records of Anastacia Majel and John P. Harrington, who recorded the language in 1933. (The tape recordings resurfaced around 1995.)[32]

Contemporary organizations

[edit]

Several organizations today identify as representing Acjachemen descendants. None of them are federally recognized,[33] and California has no process for creating state-recognized tribes.[34]

In the 1990s, the Acjachemen Nation divided into three different governments, all claiming their identity as the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation.[35]

These unrecognized organizations include:

- Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, San Juan Capistrano, CA (Petitioner 84A, originally known as the Belardes group and now referred to as 84A)[36][35]

- Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, Santa Ana, CA (Petitioner 84B)[37][35]

- Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation (Romero), Santa Ana, CA[35]

The Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation (84A), based in San Juan Capistrano elects a tribal council, assisted by tribal elders. They have about 1,800 members.[38]

In 1993, an Assembly Joint Resolution No. 48 was filed in the state of California, which "memorialized the President and Congress of the United States to declare the Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemem Nation, to be the aboriginal tribe of Orange County."[39]

in 1999, The Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation (84A) petitioned for federal recognition.[36] On November 26, 2007, the Bureau of Indian Affairs declined the petition due to not meeting the four of the seven mandatory criteria.[36]

In 2002, Acjachemen representatives expressed interest in regaining some of the territory of the former Marine Corps Air Station El Toro.[40]

In 2008, the Acjachemen community successfully prevented the construction of a toll road highway that would have desecrated and irreparably harmed Panhe, a sacred ancestral town site.[41] They also reached a legal agreement agreement with CSULB to protect the land of Puvungna, where the university is partially situated. The university made several promises to maintain the integrity of the land.[42][43]

In 2013, the 84A group of the Acjachemen Nation voted to elect the first all-female Acjachemen tribal council in its history.[44]

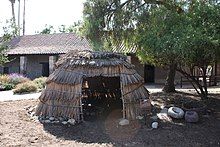

In 2021, Adelia Sandoval, Jerry Nieblas, and other Acjachemen members celebrated the opening of Putuidem Village, a 1.5-acre park (0.61 ha) in San Juan Capistrano, part of their original lands, which commemorates their history.[45]

On July 10, 2021, one of the Acjachemen Nation 84A group elected a new tribal council of Heidi Lee Lucero, Chairwoman; Dr. Richard Rodman, Vice Chairman; Ricky Hernandez, Treasurer; Georgia "Chena" Edmundson, Secretary; Sabrina Banda, Member-At-Large; and Ruth "Cookie" Stoffel, Member-At-Large.[46]

Notable Acjachemen

[edit]- José de Grácia Cruz, Father of Paul Arbiso, bell ringer, and artisan.

- Bobbie Banda, elder who established Native American education programs in public schools.[44]

- Clarence H. Lobo (1912–1985), chief, lobbyist, and spokesperson of the Acjachemen for 39 years who "was responsible for the Johnson administration reimbursing California Indians $2.9 million for the loss of their land."[47] In September 1994, the Clarence Lobo Elementary School opened in San Clemente as part of the Capistrano Unified School District. It was the first school in California to be named after a Native American leader.[48]

- Heidi Lucero, Juaneño Band of Mission Indians Acjachemen Nation - Chairwoman 2021-current. California State University Long Beach lecturer of indigenous studies.

See also

[edit]- Population of Native California

- Classification of Indigenous peoples of the Americas#California

- Mission Indians

- Indigenous peoples of California

- California mission clash of cultures

Acjachemen villages and significant sites in Southern California (a partial list):

- Acjacheme

- Ahunx

- Alauna

- Genga

- Hutuknga

- Lupukngna

- Moyongna

- Pajbenga

- Panhe

- Piwiva

- Puhú

- Puvunga

- Sejat

- Totpavit

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The appellation Juaneño does not necessarily identify a specific ethnic or tribal group, as the Spanish sometimes gathered diverse peoples to live and work as servants and slaves at their missions.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Luppi, Kathleen (June 23, 2016). "After having land stolen for generations, Juaneño Indians get a sliver back". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ Haas, Lisbeth (2014). Saints and citizens: Indigenous histories of colonial missions and Mexican California. Berkeley. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-520-95674-2. OCLC 865853684.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Loewe, Ronald (2016). Of sacred lands and strip malls : the battle for Puvungna. Lanham, MD. pp. 1–3, 120–121. ISBN 978-0-7591-2162-1. OCLC 950751182.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Haas 1996, pp. 19–23

- ^ Woodward, Lisa Louise (2007). The Acjachemen of San Juan Capistrano: The History, Language and Politics of an Indigenous California Community. University of California, Davis. pp. 3, 8.

- ^ O'Neil, Stephen; Evans, Nancy H. (1980). "Notes on Historical Juaneno Villages and Geographical Features". UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 2 (2): 226–232.

- ^ Clark, Patricia Roberts (October 21, 2009). Tribal Names of the Americas: Spelling Variants and Alternative Forms, Cross-Referenced. McFarland. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7864-5169-2.

- ^ "History". Juaneño Band of Mission Indians Acjachemen Nation. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Bean & Blackburn 1976, pp. 109–111

- ^ Boscana 1933, p. 37

- ^ a b c Tomczyk, Weronika; Acebo, Nathan P. (July 3, 2021). "Enduring Dimensions of Indigenous Foodways in the Southern Alta California Mountain Hinterlands". California Archaeology. 13 (2): 171–201. doi:10.1080/1947461X.2021.1997515. ISSN 1947-461X. S2CID 244551127.

- ^ O'Neil 2002, pp. 68–78

- ^ Lisbeth Haas, Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 20.

- ^ Kroeber 1925, p. 636

- ^ "Acjachemen History". Juaneño Band of Mission Indians. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 28–29

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 38–40

- ^ Haas 1996, p. 45

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 53–55

- ^ After Kroeber 1925[verification needed]

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 56–60

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 60–63

- ^ Haas 1996, pp. 66–68

- ^ Haas 1996, p. 118

- ^ Kelsey 1993, p. 3

- ^ Hittell 1898, p. 746

- ^ Hittell 1898, p. 749

- ^ Hittell 1898, pp. 746–747

- ^ "History". Juaneño Band of Mission Indians Acjachemen Nation. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Sparkman 1908, p. 189: Linguistically, the Acjachemen tongue is a dialect of the larger Luiseño language, which is derived from the Takic language family (Luiseño, Juaneño, Cupeño, and Cahuilla Indians all belong to the Cupan subgroup), a part of the Uto-Aztecan (Shoshone) linguistic stock (this language is sometimes referred to as "Southern California Shoshonean"). But the language at Capistrano and Soboba differed "considerably from that of the remainder of the Luiseños, and by some the people of these places are not included among the Luiseños."

- ^ Sutton, Mark (April 2010). "A Reevaluation of Early Northern Uto-Aztecan Prehistory in Alta California". California Archaeology. 2 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1179/cal.2010.2.1.3. ISSN 1947-461X. S2CID 162210224.

- ^ "CNN - Long-dead Indian teaches lost language - Mar. 30, 1996". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 88: 2112–16. January 12, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "State Recognition of American Indian Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. October 10, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Acjachemen". State of California Native American Heritage Commission. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Petition #084A: Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, CA". Office of Federal Acknowledgment. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Petition #084B: Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, CA". Office of Federal Acknowledgment. U.S. Department of the Interior. June 20, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Brazil, Ben (September 22, 2021). "New tribal leader will help the first people of O.C. in their decades-long battle to gain federal recognition". Daily Pilot. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "BILL NUMBER: AJR 48". California Legislative Information. Legislative Counsel of the State of California. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Pasco, Jean O. (March 30, 2002). "Indian casino in El Toro's Future?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (2019). As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock. Beacon Press. pp. 132–138. ISBN 978-0-8070-7378-0.

- ^ Jordan, Rachel (October 5, 2019). "CSULB under fire for dumping dirt, trash on sacred Native American grounds". Abc7 Los Angeles.

- ^ "Site Maintenance". California State University, Long Beach. April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Park, Brian (May 8, 2013). "Bobbie Banda, Juaneño Tribal Elder, Dies at 66". Capistrano Dispatch. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Brazil, Ben (December 13, 2021). "After delays, the first people of Orange County have preserved a piece of their ancestral village". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "Governance". Juaneño Band of Mission Indians Acjachemen Nation. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "Necrology". The Journal of American Indian Family Research. VI (4). HISTREE: 62. 1985.

- ^ Cekola, Anna (October 28, 1993). "A Special Groundbreaking Makes History, Remembers It". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

Works cited

[edit]- Bean, Lowell John; Blackburn, Thomas C., eds. (1976). Native California: A Theoretical Retrospective. Socorro, New Mexico: Ballena Press.

- Boscana, Gerónimo, O.F.M. (1933). Hanna, Phil Townsend (ed.). Chinigchinich: A Revised and Annotated Version of Alfred Robinson's Translation of Father Gerónimo Boscana's Historical Account of the Belief, Usages, Customs and Extravagancies of the Indians of this Mission of San Juan Capistrano Called the Acagchemen Tribe. Santa Ana, CA: Fine Arts Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haas, Lisbeth (1996). Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20704-2.

- Hittell, Theodore H. (1898). History of California, Volume I. San Francisco, CA: N.J. Stone & Company.

- Kelsey, Harry (1993). Mission San Juan Capistrano: A Pocket History. Altadena, CA: Interdisciplinary Research, Inc. ISBN 0-9785881-0-X.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

- O'Neil, Stephen (2002). The Acjachemen in the Franciscan Mission System: Demographic Collapse and Social Change (Master's thesis). Fullerton, California: Department of Anthropology, California State University.

- Sparkman, Philip Stedman (1908). "The Culture of the Luiseño Indians". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 8 (4): 187–234.

Further reading

[edit]- Feinberg, Leslie (1996). Transgender Warriors. Beacon Press, Boston, MA. ISBN 0-8070-7940-5.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1907). "The Religion of the Indians of California". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 4 (6): 318–356.

External links

[edit]- Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation, San Juan Capistrano, CA

- Reverend Father Friar Gerónimo Boscana, 1846. "Chinigchinich; a Historical Account of the Origin, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians at the Missionary Establishment of St. Juan Capistrano, Alta California Called The Acjachemen Nation", Webroots

- Traditional California Native American Acjachemen Planting Song, Indigenous Peoples Issues