Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site

| Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site | |

|---|---|

Hubbell Trading Post | |

| Location | Apache County, Arizona, United States |

| Nearest town | Ganado, Arizona |

| Coordinates | 35°43′26″N 109°33′36″W / 35.72389°N 109.56000°W |

| Area | 160 acres (65 ha) |

| Established | 1878 [1] |

| Visitors | 39,361 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site |

Hubbell Trading Post | |

Guest House | |

| Location | Ganado, Arizona |

|---|---|

| Built | 1878 |

| Architect | John Lorenzo Hubbell |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000167 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[2] |

| Designated NHL | December 12, 1960[3] |

Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site is a historic site on Highway 191, north of Chambers, with an exhibit center in Ganado, Arizona. It is considered a meeting ground of two cultures between the Navajo and the settlers who came to the area to trade. Established on August 28, 1965, Hubbell Trading Post encompasses about 65 hectares (160 acres) and preserves the oldest continuously operated trading post on the Navajo Nation.[1][4] From the late 1860s through the 1960s, the local trading post was the main financial and commercial hub for many Navajo people, functioning as a bank (where they could pawn silver and turquoise), a post office, and a store. [2]

History

[edit]The history of the trading post begins in approximately 1874, when Anglo-European trader William Leonard established a trading post in the Ganado Valley. Using “squatter’s rights”, Juan Lorenzo Hubbell purchased the Leonard post and later filed for a homestead claim.[3] In 1878, John Lorenzo Hubbell purchased this trading post, ten years after Navajos were allowed to return to the Ganado region from their U.S.-imposed exile in Bosque Redondo, Fort Sumner, New Mexico. This ended what is known in Navajo history as the "Long Walk of the Navajo." Through extensive archival research, historian Cottam (Arizona State Univ.) first tells the story of John Lorenzo Hubble and the trading empire he built, then continues with in-depth analysis of his heirs and their involvement in the Southwest ethnic art industry. And it all centers on a still-vibrant and living place.[5]

It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960.[3][6]

Navajo people

[edit]When the Navajos returned from The Long Walk in 1868, they found their herds decimated, their fields destroyed. A majority of Navajos have lived on the reservation since the Treaty of 1868. The treaty allowed surviving Navajos to return from the Bosque Redondo internment camp to a portion of their ancestral homeland, about one-fourth the size of the territory they inhabited before being displaced to Bosque Redondo. Executive orders and Congressional legislation gradually increased the size of the reservation to its current size of more than six million acres.[4] Their way of life was ripped apart and their life was forever changed. The Navajos were troubled by an economic depression in the late 19th century as a result of the Long Walk. Thus, trade became increasingly important.

Heavy sandstones from the area were quarried in 1883 to begin construction of this solid building along the southern banks of the Pueblo Colorado Wash. Life at Hubbell Trading Post centered around it. The idea of trading was not new to the Navajos. Native American tribes in the Southwest had traded amongst themselves for centuries. During the four years' internment at Bosque Redondo, Navajos were introduced to many new items (e.g., flour, sugar, coffee, baking powder, canned goods, tobacco, tools, cloth, etc.). When the Anglos came to trade with the Navajos, the difference was in the products exchanged, and in the changes brought about by these exchanges. Traders like Hubbell supplied these items.

Trade with men like Hubbell became increasingly important for the Navajos. The trader was in contact with the world outside the newly created reservation, a world which could supply the staples the Navajos needed to supplement their homegrown products. In exchange for the trader's goods the Navajos traded wool, sheep and, later, rugs, jewelry, baskets and pottery. It was years before cash was used between trader and Navajos. Since there were few towns in the region, trading posts, such as Hubbell Trading Post at Ganado, Arizona, and Goulding's Trading Post near Monument Valley, Arizona, became key places to sell weaving and silverwork during frontier times. [5]

Hubbell family members operated this trading post until it was sold to the National Park Service in 1967. The trading post is still active, operated by the non-profit Western National Parks Association, which maintains the trading traditions the Hubbell family established.

Today, Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site is still situated on the original 160-acre (65 ha) homestead, which includes the trading post, family home, out buildings, land and a visitor center. Visitors can experience this historic trading post on the Navajo Nation, which includes weaving demonstrations; and the store still maintains a wooden floor and walls from the days of old. A set of initials carved on the gate of the privacy wall which separates the public spaces from the private stand for John Lorenzo Hubbell.

Hubbell's life

[edit]Hubbell's father was Anglo, his mother Spanish. He was raised in Pajarito Mesa, New Mexico, a small village just south of Albuquerque, New Mexico. He came to this area in 1876, less than ten years after the Long Walk. In 1878 he bought the small buildings comprising the compound from a trader named William Leonard, and started business. He was twenty-three years old, single and trying to make a living among the Navajos, a people he did not know very well. He had to find a niche in a new culture, a difficult language. He probably learned "trader Navajo" very quickly. John Lorenzo was trilingual. He spoke English, Spanish and Navajo. During the first half of the 20th century, Hubbell built an economic empire consisting of more than 20 trading posts that was able to influence the production and development of traditional designs that remain in use today.[6]

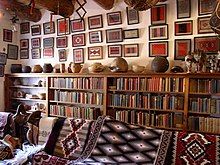

Mr. Hubbell married a Spanish woman named Lina Rubi. They had two sons and two daughters. Additions to the family home to accommodate the growing family were finished in 1902. It started out as a plain adobe building which the Hubbell family gradually made into a comfortable, and in some ways, luxurious home. Paintings and artifacts and many large Navajo rugs still decorate the interior. Unlike other traders who left their families "back home" in the east, the entire Hubbell family spent most of the year in the village of Ganado. The Hubbells lived in the house until 1967.

The guest house was built in the early 1930s by Roman and Dorothy Hubbell, Mr. Hubbell's son and daughter-in-law, as a tribute to Mr. Hubbell. Dorothy Hubbell carved the inner wooden door. Visitors stayed in the Hubbell home, such as artists who were interested in the color and shapes of the land; anthropologists who came to Mr. Hubbell for information; statesmen; friends of the family; and ordinary travelers in need of a place to stay. Architecturally, the guest house is in the Hogan (pronounced hoe-gone) (Navajo for home) style. Most hogans are built of logs, and the door always faces the east. Hogans are one-room dwellings and usually have six or eight sides. Mr. Hubbell built several traditional hogans on the grounds for the Navajos who came long distances to trade. The guest house was originally called Pueblo Colorado (the inscription over the door) but often was confused with the town of Pueblo, Colorado. There was an important Navajo leader named totsohnii Hastiin (pronounced Toe-so-knee haaus-teen) (Navajo for "man of the big water clan"). He was also called Ganado Mucho (pronounced gah-nah-doe-moo-cho) (Spanish for "many cattle") and Mr. Hubbell renamed this place Ganado for him. Ganado Mucho had a son, Many Horses, who is buried on the property.

Beyond the perimeter wall to the north courses the Pueblo Colorado Wash, the northern boundary of the Hubbell settlement. In some sections of the Ganado-Cornfields valley, the wash is spring-fed and runs year round. Melting snows in spring and heavy summer rains sometimes cause it to flood. In the Southwest a good source of water has always attracted people. The ancestral Puebloans lived in small villages up and down the valley hundreds of years ago. The Navajos came later, and then the traders - all attracted to the source of water. The Navajo called the ancestral Puebloans the Anasazi (pronounced ah-nuh-saa-zee) (Navajo for "the ancient ones").

The cone-shaped hill located northwest of the trading post is Hubbell Hill. The family cemetery is at the top. Mr. Hubbell, his wife, three of his children, a daughter-in-law, a granddaughter, and a Navajo man named Many Horses are buried there. Many Horses was one of the local herdsmen and the son of Ganado Mucho. He and Mr. Hubbell were close friends for many years. Mr. Hubbell maintained a friendship with many of his customers until his death in 1930. Then his younger son Roman operated the business. When Roman died in 1957, his wife Dorothy managed the store for another ten years, until 1967 when the National Park Service acquired the site.

Built with juniper logs upright in the ground, the corrals of the trading post held lambs and sheep purchased from Navajo stockmen by Mr. Hubbell. The flocks stayed in the corral complex until they could be herded to the railroad. From time to time Mr. Hubbell kept beef cattle as well. Mr. Hubbell homesteaded 160 acres (65 ha) before they were part of the reservation and territory. When the reservation expanded, it surrounded the Hubbell property. Through an act of Congress Mr. Hubbell got permission to keep his home. Freight wagons brought supplies 56 mi (90 km) to the store from the little railroad town of Gallup, New Mexico, two to four days' travel in good weather. Going back to Gallup, freight wagons hauled huge sacks of wool.

Construction

[edit]The national historic site consists primarily of a historic vernacular landscape from the period (1878–1967).[7] Construction of the trading post barn began in 1897. The builders, local people, made the walls of local sandstone and the roofs fashioned in the ancient Anasazi-style dwellings. Ponderosa pine beams, aspen poles, juniper bark, cornstalks, and dirt make up layers, each at right angles to the one below it. Mules and pulleys lifted the beams into place. The timbers came from about twelve miles (19 km) east of Ganado Village where it is high enough for Ponderosa to grow. The aspen poles came from farther away in the Chuska Mountains that straddle the Arizona/New Mexico state line one hundred miles north to the intersection with Colorado and Utah. The barn was completed in 1900.

See also

[edit] Arizona portal

Arizona portalNational Register of Historic Places portal

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Apache County, Arizona

- Navajo trading posts

References

[edit]- ^ "NPGallery Asset Detail".

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hubbell Trading Post". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ "NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, Arizona (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Gale - Product Login". galeapps.gale.com. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ ""Hubbell Trading Post", December 13, 1961, by Albert H. Schraeder(sp?)". National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. National Park Service. December 13, 1961.

Further reading

[edit]- Paul D. Berkowitz (2011), The Case of the Indian Trader, University of New Mexico Press ISBN 978-0-8263-4860-9, ISBN 978-0-8263-4859-3

- Erica Cottam (2020), Hubbell Trading Post: Trade, Tourism, and the Navajo Southwest, University of Oklahoma Press ISBN 978-0806167527, OCLC 1151810810

External links

[edit] Media related to Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Hubbell Trading Post, operated by the Western National Parks Association

- American Southwest, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. AZ-59, "J. L. Hubbell Trading Post, HB-1, State Route 3 (Navajo Indian Reservation), Ganado, Apache County, AZ"

- https://wnpa.org/hubbell-trading-post/

- HABS No. AZ-60, "J. L. Hubbell Trading Post, House"

- HABS No. AZ-61, "J. L. Hubbell Trading Post, Two-Story Barn"

- HABS No. AZ-62, "J. L. Hubbell Trading Post, Unfinished Shed"

- 1965 establishments in Arizona

- Buildings and structures in Apache County, Arizona

- Geography of the Navajo Nation

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Arizona

- Historic house museums in Arizona

- Museums in Apache County, Arizona

- National Historic Sites in Arizona

- National Historic Landmarks in Arizona

- Native American museums in Arizona

- Protected areas established in 1965

- Protected areas of Apache County, Arizona

- Trading posts in Arizona

- National Register of Historic Places in Apache County, Arizona