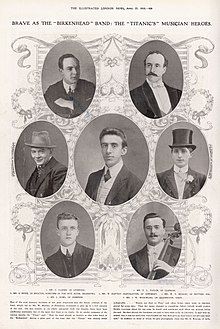

Musicians of the Titanic

Not pictured: Bricoux

The musicians of the Titanic were an octet orchestra who performed chamber music in the first class section aboard the ship.

The group is notable for playing music, intending to calm the passengers for as long as they possibly could, during the ship's sinking in the early hours of April 15, 1912 in which all of the members perished.

Timeline

[edit]Eight musicians – members of a three-piece ensemble and a five-piece ensemble – were booked through C. W. & F. N. Black, in Liverpool.[1] They boarded at Southampton and traveled as second-class passengers. They were not on the White Star Line's payroll but were contracted to White Star by the Liverpool firm of C. W. & F. N. Black, who placed musicians on almost all British liners. Until the night of the sinking, the players performed as two separate groups: a quintet led by violinist and official bandleader Wallace Hartley, that played at teatime, after-dinner concerts, and Sunday services, among other occasions; and the violin, cello, and piano trio of Georges Krins, Roger Bricoux, and Theodore Brailey, that played at the À La Carte Restaurant and the Café Parisien.[2]

After the Titanic hit an iceberg and began to sink, Hartley and his fellow band members started playing music to help keep the passengers calm as the crew loaded the lifeboats. Many of the survivors said that Hartley and the band continued to play until the very end. Reportedly, their final tune was the hymn "Nearer, My God, to Thee",[3] although other sources suggest it was "Songe d'Automne" (also known simply as "Autumn"). One second-class passenger said:

Many brave things were done that night, but none were more brave than those done by men playing minute after minute as the ship settled quietly lower and lower in the sea. The music they played served alike as their own immortal requiem and their right to be recalled on the scrolls of undying fame.[4]

All eight musicians died in the sinking.[5]

Musicians

[edit]| Name | Age | Hometown | Country | Position | Body | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Brailey | 24 | London | England | Pianist | – | [6] |

| Roger Bricoux | 20 | Cosne-sur-Loire | France | Cellist | – | [7] |

| John Clarke | 28 | Liverpool, Merseyside | England | Bassist | 202MB | [8] |

| Wallace Hartley | 33 | Colne, Lancashire | England | Bandmaster, violinist | 224MB | [9] |

| Jock Hume | 21 | Dumfries | Scotland | Violinist | 193MB | [10] |

| Georges Krins | 23 | Spa | Belgium | Violinist | – | [11] |

| Percy Taylor | 40 | London | England | Cellist | – | [12] |

| John Wesley Woodward | 32 | West Bromwich | England | Cellist | – | [13] |

William Brailey

[edit]William Theodore Ronald Brailey | |

|---|---|

| Born | 25 October 1887 |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 24) |

| Occupation | Pianist |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1902–1907 |

| Unit | Lancashire Fusiliers |

William Theodore Ronald Brailey (25 October 1887 – 15 April 1912) was an English pianist.[5][6] Born on 25 October 1887 in Walthamstow in Greater London (then part of Essex),[14] he was the son of William "Ronald" Brailey, a well-known figure of Spiritualism.[15] Brailey studied piano at school, and one of his first jobs was performing in a local hotel.[16]

In 1902, he joined the Royal Lancashire Fusiliers regiment signing for 12 years service as a musician.[17] He was stationed in Barbados but left the army prematurely in 1907.[18] He returned to England and lived at 71 Lancaster Road, Ladbroke Grove, London.[6] In 1911, he enlisted aboard ship, playing first on the Saxonia, prior to joining the Cunard steamer RMS Carpathia in 1912, where he met the French cellist Roger Bricoux. Both men then joined the White Star Line and were recruited by Liverpool music agency C. W. & F. N. Black to serve on the Titanic.[6][19] Brailey boarded the Titanic on Wednesday 10 April 1912 in Southampton. His ticket number was 250654, the ticket for all the members of Hartley's orchestra. His cabin was in the second class quarters.[4][6][20]

Brailey was 24 years old when he died; his body was never recovered.[6][21]

Roger Bricoux

[edit]Roger Marie Bricoux | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 June 1891 |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 20) |

| Occupation | Cellist |

Roger Marie Bricoux (1 June 1891 – 15 April 1912) was a French cellist.[22] Born on 1 June 1891 in Rue de Donzy, Cosne-Cours-sur-Loire, France,[23] Bricoux was the son of a musician. The family moved to Monaco when he was a young boy,[24] and he was educated in various Catholic institutions in Italy.[25] It was during his studies that he joined his first orchestra and won first prize at the Conservatory of Bologna for musical ability.[26] After studying at the Paris Conservatory, he moved to England in 1910 to join the orchestra in the Grand Central Hotel in Leeds.[27] At the end of 1911, he moved to Lille, France, lived at 5 Place du Lion d'Or, and played in various locations throughout the city.[4]

Before joining the Titanic, Bricoux had served with Brailey on the Cunard steamer Carpathia before joining the White Star Line.[4][26][7] He boarded the Titanic on Wednesday 10 April 1912 in Southampton.[26] His ticket number was 250654, the ticket for all the members of Hartley's orchestra. His cabin was second class, and he was the only French musician aboard the Titanic.[28]

Bricoux was 20 years old when he died;[26] his body was never recovered.[4]

In 1913, after his apparent disappearance, he was declared a deserter by the French army. It was not until 2000 that he was eventually officially registered as dead in France, mainly due to the efforts of the Association Française du Titanic.[29] On 2 November 2000, the same association unveiled a memorial plaque to Bricoux in Cosne-Cours-sur-Loire.[23][29]

Wallace Hartley

[edit]Wallace Henry Hartley (2 June 1878 – 15 April 1912), an English violinist, was the bandleader on the Titanic. Hartley's body was recovered by the CS Mackay-Bennett,[30] before being returned to England for burial in his home town of Colne, Lancashire.

The violin that he used on the Titanic was found in its case strapped to his body. It is now on display at the Titanic Museum in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.

Jock Hume

[edit]John Law Hume | |

|---|---|

| Born | 9 August 1890 Dumfries, Scotland |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 21) Atlantic Ocean |

| Burial place | Fairview Lawn Cemetery, Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Occupation | Violinist |

John Law "Jock" Hume (9 August 1890 – 15 April 1912) was a Scottish violinist.[31] Hume was born on 9 August 1890 in Dumfries, Scotland and lived with his parents at 42 George Street, Dumfries.[31] He had already played on at least five ships before the Titanic, and was recruited to play on its maiden voyage due to his good reputation as a musician.[32]

Hume spent the winter of 1910/1911 in Kingston, Jamaica, where he performed in the Orchestra for the Constant Spring Hotel, a grand resort of the time. Future Titanic cellist John Woodward was also a member of the Constant Spring Orchestra. During his four months in Jamaica, Hume entered a relationship with barmaid Ethel McDonald. Hume left Jamaica in April 1911, and Ethel gave birth to their child, Keith Neville McDonald Hume, in November 1911.[33]

He boarded the Titanic on Wednesday 10 April 1912 in Southampton. His ticket number was 250654, the ticket for all the members of Hartley's orchestra. His cabin was in the second class quarters.

Hume was 21 years old when he died and his fiancée, Mary Costin, was pregnant with his child.[32] His body was recovered by the CS Mackay-Bennett,[10] and was passed into the care of John Henry Barnstead who arranged for his burial in grave 193 of the designated Titanic plot at Fairview Lawn Cemetery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on 8 May 1912.[10][34][35] A memorial was erected for Hume and Thomas Mullin (third class steward) in Dock Park, Dumfries. It reads:

In memory of John Law Hume, a member of the band and Thomas Mullin, steward, natives of these towns who lost their lives in the wreck of the White Star Liner Titanic which sank in mid-Atlantic on the 14th day of April 1912. They died at the post of duty.[34]

Hume and the other members of Hartley's orchestra all belonged to the Amalgamated British Musicians Union and were employed by a Liverpool music agency, C. W. & F. N. Black, which supplied musicians for Cunard and the White Star Line.[10][36][37] On 30 April 1912, Hume's father, Andrew, received the following note from the agency:

Dear Sir:

We shall be obliged if you will remit us the sum of 5s. 4d. [five shillings and sixpence], which is owing to us as per enclosed statement.

We shall also be obliged if you will settle the enclosed uniform account.

Yours faithfully,

The letter caused controversy at the time when it was reprinted in the Amalgamated Musicians Union's monthly newsletter.[36] Andrew Law Hume decided not to settle the bill.[37]

In April 1914 John W. Furness, the violinist of the Canadian liner RMS Empress of Ireland made a pilgrimage with Anglican Church officials to visit the grave of John Law Hume at the Fairview Lawn Cemetery and pay his respects. Furness himself died in a shipwreck only a few weeks later when Empress of Ireland sank on 29 May 1914.[38]

Georges Krins

[edit]Georges Alexandre Krins | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 March 1889 Paris, France |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 23) |

| Occupation | Violinist |

Georges Alexandre Krins (18 March 1889 – 15 April 1912) was a Belgian violinist.[11] Born on 18 March 1889 in Paris, France,[39] his family was from Belgium, and soon after his birth they moved back there to the town of Spa. He first studied at Academie de Musique de Spa. He then moved to the Conservatoire Royal de Musique in Liège, Belgium, where he studied from 30 October 1902 until 1908, when he won first prize for violin, with the highest distinction.[40][4][11]

As a young man he wanted to join the army; however, his parents persuaded him otherwise.[11] He worked in his father's shop and played in La Grande Symphonie, Spa, and in 1910 he moved to Paris to be first violin at Le Trianon Lyrique.[11] He subsequently moved to London and played for two years at the Ritz Hotel until March 1912.[11] He lived at 10 Villa Road, Brixton, London and became bandmaster of the Trio String Orchestra, which played near the Café Français.[11] This led to his being recruited by CW & FN Black, Liverpool to play on the Titanic.[4]

He boarded the Titanic on Wednesday 10 April 1912 in Southampton. His ticket number was 250654, the ticket for all the members of Hartley's orchestra.[11] His cabin was second class, and he was the only Belgian musician aboard the Titanic. After the Titanic began to sink, Krins and his fellow band members assembled in the first class lounge and started playing music to help keep the passengers calm. They later moved to the forward half of the boat deck, where they continued to play as the crew loaded the lifeboats. Krins was 23 years old when he died. His body was never recovered.[4][11][41]

Memorial concert

[edit]A memorial concert for the Bandsmen of the Titanic was held at the Royal Albert Hall on Friday 24 May to raise funds to support the families of the musicians lost at sea.[42] Musicians from the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Queen's Hall Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra,[43] the New Symphony Orchestra, the Beecham Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Opera Orchestra, and the London Opera House Orchestra[44] made up an orchestra of around 500 players.[45] Ada Crossley opened the concert with Felix Mendelssohn's Oh Rest in the Lord from Elijah, with the rest of the programme consisting of solemn orchestral items including works by Elgar, Tchaikovsky and Wagner, with Chopin's Funeral March and Arthur Sullivan's "In Memoriam". Seven conductors led the orchestra, Sir Edward Elgar, Sir Henry Wood, Landon Ronald, Percy Pitt, Thomas Beecham, Fritz Ernaldy and Willem Mengelberg.[46] The audience joined in singing "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as orchestrated by Sir Henry Wood to close the concert. A photograph of the event hangs in the Royal Albert Hall outside the loggia boxes.[47]

Memorials

[edit]-

RMS Titanic Musician's Memorial, Southampton

-

Titanic Bandsmen Memorial monument in Broken Hill, Australia (1913)

-

SS Titanic Memorial Bandstand in Ballarat, Australia (1915)

In media

[edit]Film

[edit]Two documentary films have been made about the Titanic's band.

- The British film, Titanic: The Band Played On (completed in 2012), was shown on Yesterday television.[48]

- The American Film, Titanic–Band of Courage (2014), was shown on Public Broadcasting System stations.[49]

Literature

[edit]Books written specifically about the Titanic's musicians include:

- Steve Turner's nonfiction book, The Band that Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the 8 Musicians Who Went Down with the Titanic (2011)[1]

- Christopher Ward's non-fiction book, And the Band Played On: The Titanic Violinist and the Glovemaker: A True Story of Love, Loss and Betrayal (2011),[50] which became a Sunday Times bestseller and was made into a documentary for the Discovery Channel titled, Titanic: The Aftermath (2012).[51] The book details the story of Ward's grandfather, Jock Hume.[52][53]

Music

[edit]- Chamber music ensemble I Salonisti performs Titanic repertoire on the album And the Band Played On (Music Played on the Titanic) (1997),[54] including the Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana. The White Star orchestra played this famous piece from Mascagni's opera after dinner in Titanic's lounge on 10 April 1912, according to passenger Father Browne.[55]

- Minimalist work The Sinking of the Titanic (1969–1972) by composer Gavin Bryars is meant to recreate how the music performed by the band would reverberate through the water some time after they ceased performing.

- Harry Chapin's album Dance Band on the Titanic (1977) is dedicated to the Titanic's ensembles and contains a song titled "Dance Band on the Titanic"

- The album Titanic: Music As Heard On The Fateful Voyage (1997),[56] by Ian Whitcomb and the White Star Orchestra, recreates songs played aboard the Titanic the night the ship foundered, and includes detailed liner notes about the music and excursion.

Theatre

[edit]- The 1997 musical Titanic, with music and lyrics by Maury Yeston and a book by Peter Stone that opened on Broadway, is set on the ocean liner. It swept the 1997 musical Tony Awards winning all five it was nominated for including the award for Best Musical and Best Score (Yeston's second for both). It ran for 804 performances at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre.[57] Hartley is the only named character in the musical, while the rest of the band itself only makes an appearance in one music number.

See also

[edit]- Crew of the Titanic

- Four Chaplains – American military chaplains lost on the SS Dorchester during World War II

- HMS Birkenhead (1845) – British troopship disaster, the origin of the Birkinhead Drill.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Turner 2011.

- ^ "Titanic's Band or Orchestra". Titanic-Titanic.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- ^ "Denis Kilcommons: Which version of Nearer My God to Thee did Wallace Hartley play as Titanic went down?". 12 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kopstein, Jack (2011). "The Valiant Musicians | World Military Bands". worldmilitarybands.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b Kopstein, Jack (2011). "The Valiant Musicians |". World Military Bands. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "William Theodore Ronald Brailey". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 21 December 1998. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Roger Marie Bricoux". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 23 May 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "John Frederick Preston Clarke". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Wallace Henry Hartley". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Jock Hume". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. August 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Georges Alexandre Krins". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 27 June 2002. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Percy Cornelius Taylor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "John Wesley Woodward". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. Encyclopedia Titanica. 29 January 1998. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 62.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 68.

- ^ Whitfield, Geoff; Mendez, Olivier (2011). "Mr Roger Marie Bricoux". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Second Class Passengers". titanicsite.kit.net. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Theodore Ronald Brailey – 2nd Class Passenger on the Titanic from England – Brailey – Family History & Genealogy Message Board". Ancestry.co.uk. 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Ancestry.co.uk (2011). "Roger-Marie Bricoux – Passenger on the Titanic from Monaco – General – Family History & Genealogy Message Board". boards.ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

1 June 1891

- ^ a b Titanic-Titanic (2011). "Titanic-Titanic.com • View topic – Roger Bricoux [cellist]". titanic-titanic.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

rue de Donzy

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d Sha're (2011). "Roger Bricoux [violoncelliste]". titanic.superforum.fr. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Turner 2011, p. 52.

- ^ titanicsite (2007). "Titanic Site". titanicsite.kit.net. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b Mendez, Olivier (2011). "Memorial to Roger Bricoux, Titanic cello player (2000) – 2 November 2000". encyclopedia-titanica.org. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

On November 2nd 2000, the Association Francaise du Titanic unveiled a memorial plaque in memory of Roger Bricoux in Cosne-sur-Loire, the city where he was born on June 1st 1891. In 1913, Roger had been considered a desertor by the French army, and it was not before 2000, thanks to the AFT's work, that he was officially registered as... dead.

- ^ "Titanic band leader's violin is authentic, say experts". News Wiltshire. BBC. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ a b Ancestry.com (2011). "John Law Hume". homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b Blackmore, David (2011). "Boughton resident's book reveals tale of young bandsman on Titanic". Norwich Evening News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

He played on at least five ships before the Titanic and he was put forward to play on the ship because they really wanted to cream of the crop to play for passengers. It was such a famous ship and the largest liner at the time and that's what made John really want to be on its maiden voyage.

- ^ "And the Band Played on".

- ^ a b Titanic Remembered (2011). "Titanic Remembered – in Dumfries". maritime.elettra.co.uk. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

in grave 193

- ^ Ancestry.com (2011). "John Law Hume – Musician on the Titanic from England – Hume – Family History & Genealogy Message Board". boards.ancestry.com. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

Burial: Fairview Lawn Cemetery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on Friday 3rd May 1912

- ^ a b Laing, Peter (2011). "Callous demand on family of Scots violinist who played as Titanic sank | Deadline News". deadlinenews.co.uk. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b Darroch, Gordon (2011). "A bad note: the bill sent to Titanic violinist who played on as the ship went down | Glasgow and West | STV News". news.stv.tv. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "The Orchestra were Favourites in Halifax", Halifax Evening Mail, 30 May 1914

- ^ Titanic-Titanic.com (2011). "Titanic Memorial – George Krins, Spa, Belgium". titanic-titanic.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ "The Brave Bandsmen – A Belgian Memorial :: Liverpool Echo – 25 April 1912". encyclopedia-titanica.org. 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Passenger 47 (2011). "Titanic 4 You Chat Forums :: View topic – The Titanic's Band / Orchestra". hostmybb.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jacky Cowdrey (10 May 2012). "From the Archives: The Titanic Band Memorial Concert". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Titanic Band memorial concert, 1912". Classic FM (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "The Titanic Band Memorial Concert". www.dennisbrain.net. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "The Titanic Band Memorial Concert". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "Historypin". Historypin. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ John Willians (14 June 2017). "From the Archive: conserving the Titanic Band Memorial Concert photograph". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "The Titanic's band remembered in new TV documentary The Band Played On". Liverpool Echo. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Titanic – Band of Courage". Cinando. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Ward, Christopher (2011). And The Band Played On: The Titanic Violinist and the Glovemaker: A True Story of Love, Loss and Betrayal. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9781444707977.

- ^ Devan, Subhadra (30 March 2012). "That sinking feeling". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Ward, Christopher (29 February 2012). "What Happened To My Grandfather After the Titanic Sank". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Davenport-Hines, Richard (20 August 2011). "Book reviews: When the great ship went down". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "And the Band Played On: Music Played on the Titanic". Discogs. 1997. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Queenstown locals believed Titanic touched by devil". www.independent.ie. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Whitcomb, Ian (10 June 1997). Titanic: Music As Heard On The Fateful Voyage (Audio Cassette ed.). Wea Corp. ASIN B0000063DP.

- ^ Brantley, Ben." 'Titanic,' the Musical, Is Finally Launched, and the News Is It's Still Afloat" New York Times, 24 April 1997

Sources

- Turner, Steve (22 March 2011). The Band that Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the 8 Musicians Who Went Down with the Titanic. Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 9781595552198 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

[edit]- Hume, Yvonne; Hume, John Law (2011). RMS Titanic 'The First Violin': The true story of Titanic's first violinist. Millvina Dean (foreword) (hardcover ed.). ISBN 9781840335217. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2018. Yvonne Hume is John Law "Jock" Hume's great niece.[1]

- Ward, Christopher (2011). And The Band Played On: The Titanic Violinist and the Glovemaker: A True Story of Love, Loss and Betrayal. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9781444707977. Christopher Ward is John "Jock" Law Hume's grandson.[2]

External links

[edit]- Memorial to the Titanic Cellists

- Theodore Ronald Bailey

- Roger Marie Bricoux

- John Law Hume (or Hulme)

- Georges Alexandre Krins

References

[edit]- ^ "Home: Welcome". Yvonne Hume Official Website. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Meet the Author". And the Band Played On. Retrieved 28 November 2015.