Augustus John

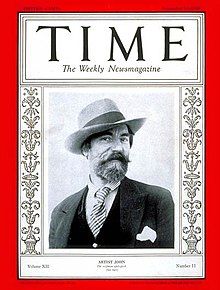

Augustus John | |

|---|---|

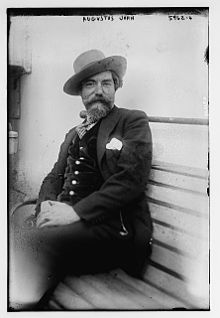

John in 1902 by George Charles Beresford | |

| Born | Augustus Edwin John 4 January 1878 Tenby, Pembrokeshire, Wales |

| Died | 31 October 1961 (aged 83) Fordingbridge, Hampshire, England |

| Known for | painter |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Dorothy "Dorelia" McNeill |

| Children | various, including Casper, Vivien, Gwyneth, Amaryllis, and Tristan |

| Relatives | Gwen John (sister) |

| Awards | Order of Merit Royal Academician |

Augustus Edwin John OM RA (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961) was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf remarked that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sargent and Charles Wellington Furse "... was over. The age of Augustus John was dawning."[1] He was the younger brother of the painter Gwen John.

Early life

[edit]Born in Tenby, at 11, 12 or 13 The Esplanade, now known as The Belgrave Hotel, Pembrokeshire, John was the younger son and third of four children.[2] His father was Edwin William John, a Welsh solicitor; his mother, Augusta Smith (1848–1884), from a long line of Sussex master plumbers,[3] died when he was six, but not before inculcating a love of drawing in both Augustus and his older sister Gwen.[4] At the age of seventeen he briefly attended the Tenby School of Art, then left Wales for London, studying at the Slade School of Art, University College London. He became the star pupil of drawing teacher Henry Tonks and even before his graduation he was considered the most talented draughtsman of his generation.[5] His sister, Gwen was with him at the Slade and became an important artist in her own right.[6] In the 1890s, John lodged in studios at Tite Street, Chelsea.[7]

In 1897, John hit submerged rocks diving into the sea at Tenby, suffering a serious head injury; the lengthy convalescence that followed seems to have stimulated his adventurous spirit and accelerated his artistic growth.[2][8] In 1898, he won the Slade Prize with Moses and the Brazen Serpent. John afterward studied independently in Paris where he seems to have been influenced by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.[9]

The need to support Ida Nettleship (1877–1907), whom he married in 1901, led him to accept a post teaching art at the University of Liverpool.[10]

North Wales

[edit]Over a period of two years from around 1910 Augustus John and his friends James Dickson Innes and Derwent Lees[11] painted in the Arenig valley, and one of Innes's favourite subjects was the mountain Arenig Fawr. In 2011 this period was made the subject of a BBC documentary titled The Mountain That Had to Be Painted.[12]

Alderney Manor

[edit]Alderney Manor, Dorset, was sited on the Poole to Ringwood road between Knighton Bottom and Howe Corner from the early 19th century.[13] John established an artists' colony there in 1911. Faye Hammill relates how he lived there with "his five legitimate children, his mistress Dorelia McNeill, and his two children by her; and they remained there until 1927, in the company of numerous long-term guests".[14] One frequent visitor was fellow artist Henry Lamb. Aspects of John's life during this period were used as background by Margaret Kennedy in her novel The Constant Nymph (1924).[15] A housing estate now occupies the site.

Provence

[edit]In February 1910, John visited and fell in love with the town of Martigues, in Provence, located halfway between Arles and Marseilles, and first seen from a train en route to Italy.[16] John wrote that Provence "had been for years the goal of my dreams" and Martigues was the town for which he felt the greatest affection. "With a feeling that I was going to find what I was seeking, an anchorage at last, I returned from Marseilles, and, changing at Pas des Lanciers, took the little railway which leads to Martigues. On arriving my premonition proved correct: there was no need to seek further."[17] The connection with Provence continued until 1928, by which time John felt the town had lost its simple charm, and he sold his home there.[18]

John was, throughout his life, particularly interested in the Romani people (whom he referred to as "Gypsies"), and sought them out on his frequent travels around the United Kingdom and Europe, learning to speak various versions of their language. For a time, shortly after his marriage, he and his family, which included his wife Ida, mistress Dorothy (Dorelia) McNeill, and John's children by both women, travelled in a caravan, in gypsy fashion.[19] Later on he became the President of the Gypsy Lore Society, a position he held from 1937 until his death in 1961.[20]

By 1913, John was successful enough to commission a new home and studio at Mallord Street, Chelsea, from architect Robert van 't Hoff.[7]

War

[edit]In December 1917 John was attached to the Canadian forces as a war artist and made a number of memorable portraits of Canadian infantrymen. The result was to have been a huge mural for Lord Beaverbrook and the sketches and cartoon for this suggest that it might have become his greatest large-scale work. However, like so many of his monumental conceptions, it was never completed. As a war artist, John was allowed to keep his beard; according to Wyndham Lewis, John was "the only officer in the British Army, except the King, who wore a beard."[21] After two months in France he was sent home in disgrace after taking part in a brawl.[22] Lord Beaverbrook, whose intervention saved John from a court-martial, sent him back to France where he produced studies for a proposed Canadian War Memorial picture, although the only major work to result from the experience was Fraternity.[23] In 2011, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge finally unveiled this mural at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. This unfinished painting, The Canadians Opposite Lens, is 12 feet high by 40 feet long.[24]

Portraits

[edit]

Although known early in the century for his drawings and etchings, the bulk of John's later work consisted of portraits. Those of his two wives and his children were regarded as among his best.[citation needed] He was known for the psychological insight of his portraits, many of which were considered "cruel" for the truth of the depiction. Lord Leverhulme was so upset with his portrait that he cut out the head (since only that part of the image could easily be hidden in his vault) but when the remainder of the picture was returned by error to John there was an international outcry over the desecration.[25]

By the 1920s John was Britain's leading portrait painter. John painted many distinguished contemporaries, including T. E. Lawrence, Thomas Hardy, W. B. Yeats, Aleister Crowley, Lady Gregory, Tallulah Bankhead, George Bernard Shaw, the cellist Guilhermina Suggia, the Marchesa Casati and Elizabeth Bibesco. Perhaps his most famous portrait is of his fellow-countryman, Dylan Thomas, whom he introduced to Caitlin Macnamara, his sometime lover who later became Thomas's wife.[26] Portraits of Dylan Thomas by John are held at National Museum Cardiff and the National Portrait Gallery.[27] A commissioned copy of the portrait of T. E. Lawrence was made by Alix Jennings at the request of Jesus College to be its memorial to Lawrence.[28][29][30][31]

It was said that after the war his powers diminished as his bravura technique became sketchier.[32] One critic has claimed that "the painterly brilliance of his early work degenerated into flashiness and bombast, and the second half of his long career added little to his achievement." However, from time to time his inspiration returned, as it did on a trip to Jamaica in 1937.[33] The works done in Jamaica between March and May 1937 evidence a resurgence of his powers, and amounted to "the St. Martin's summer of his creative genius".[34] In 1944, Sir Bernard Montgomery commissioned a portrait of himself, but rejected the completed work "because it was not like me"; it was subsequently purchased by the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow.[35]

Of his method for painting portraits John explained:[36]

Make a puddle of paint on your palette consisting of the predominant colour of your model's face and ranging from dark to light. Having sketched the features, being most careful of the proportions, apply a skin of paint from your preparation, only varying the mixture with enough red for the lips and cheeks and grey for the eyeballs. The latter will need touches of white and probably some blue, black, brown, or green. If you stick to your puddle (assuming that it was correctly prepared), your portrait should be finished in an hour or so, and be ready for obliteration before the paint dries, when you start afresh.

Family

[edit]

On 24 January 1901, John married Ida Nettleship (1877–1907), daughter of the artist John Trivett Nettleship, and a fellow student at the Slade. The couple had five sons: David John (1902–1974).,[2] Caspar John (1903–1984), Robin John (1904–1988), Edwin John (1905–1978), and Henry John (1907–1935). Despite the fact that Nettleship was John's wife, housekeeper, and the mother of five of his children, there is not a single mention of her in Chiaroscuro, his 1952 memoir. From 1905 until her death in 1907, Ida lived in Paris with John's mistress Dorothy "Dorelia" McNeill; a Bohemian style icon, she lived with John for the rest of their lives, having four children together, though they never married.[37] One of his sons (by his wife Ida) was the prominent British Admiral and First Sea Lord Sir Caspar John. His daughter with Dorelia, Vivien John (1915–1994), was a notable painter.[38]

By Ian Fleming's widowed mother, Evelyn Ste Croix Fleming, née Rose, he had a daughter, Amaryllis Fleming (1925–1999), who became a noted cellist. Another of his sons, by Mavis de Vere Cole, wife of the prankster Horace de Vere Cole, is the television director Tristan de Vere Cole. His son Romilly (1906–1986) was in the RAF, briefly a civil servant, then a poet, author and an amateur physicist. Poppet (1912–1997), John's daughter by Dorothy, married the Dutch painter Willem Jilts Pol (1905–1988). Willem Pol's daughter Talitha (1940–1971) by an earlier marriage (i.e. step-granddaughter of both Augustus and Dorothy), a fashion icon of 1960s London, married John Paul Getty Jr. His daughter Gwyneth Johnstone (1915–2010), by musician Nora Brownsword, was an artist.[39] Augustus John's promiscuity gave rise to rumours that he had fathered as many as 100 children.[40]

In a 1977 interview, Caitlin Thomas was asked about her family's friendship with Augustus John and the rumors surrounding his promiscuity. When asked if John "pounced on" her, she replied, "Oh yes, constantly, and on his daughters."[41]

Later life

[edit]

In later life, John wrote two volumes of autobiography, Chiaroscuro (1952) and Finishing Touches (1964).[42] In old age, although John had ceased to be a moving force in British art, he was still greatly revered, as was demonstrated by the huge show of his work mounted by the Royal Academy in 1954. He continued to work up until his death in Fordingbridge, Hampshire in 1961, his last work being a studio mural in three parts, the left hand of which showed a Falstaffian figure of a French peasant in a yellow waistcoat playing a hurdy-gurdy while coming down a village street. It was Augustus John's final wave goodbye.

He joined the Peace Pledge Union as a pacifist in the 1950s, and was a founder member of the Committee of 100. On 17 September 1961, just over a month before his death, he joined the Committee of 100's's anti-nuclear weapons demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London. At the time, his son, Admiral Sir Caspar John was First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff. He died at Fordingbridge, aged 83.[43]

He is said to have been the model for the bohemian painter depicted in Joyce Cary's novel The Horse's Mouth, which was later made into a 1958 film of the same name with Alec Guinness in the lead role.

Michael Holroyd published a biography of John in 1975 and it is a mark of the public's continued interest in the painter that Holroyd published a new version of the biography in 1996. A major exhibition, 'Gwen John and Augustus John,' was held at Tate Britain over the winter of 2004/5. According to the gallery's publicity, this exhibition revealed 'that although Augustus described himself and his sister as "the same thing, really," their art developed in different directions. Augustus' work seems wildly exuberant against Gwen's more introverted approach, but both artists indicate a similar flight from the modern world into a realm of fantasy.[44] The exhibition went on to the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff later in 2005. In 2018 Poole Museum in Dorset hosted the exhibition 'Augustus John: Drawn from Life,' which then went on to Salisbury Museum in 2019.

Honours and reputation

[edit]Early in his career John became a leading figure in the New English Art Club, where he frequently exhibited in the years up to the First World War. With his vivid manner of portraiture and his ability to catch unerringly some striking and usually unfamiliar aspect of his subject, he superseded Sargent as England's fashionable portrait painter. In 1921, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy and elected a full R.A. in 1928. He was named to the Order of Merit by George VI in 1942. He was a trustee of the Tate Gallery from 1933 to 1941, and President of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters from 1948 to 1953. He was awarded the Freedom of the Town of Tenby on 30 October 1959.[45] On his death in 1961, an obituary in The New York Times observed, 'He was regarded as the grand old man of British painting, and as one of the greatest in British history.' [46]

John's granddaughter Rebecca John, the leading authority on her grandfather, said in 2024, while praising his earlier work, that "most [paintings since the 1930s] should have been burned. My grandfather went down the drain from the 1930s onwards, drank too much, lost his judgment, and took every opportunity to earn money from portraits of society ladies and the wives of notable men".[47]

Collections

[edit]His work is held in the permanent collections of many museums worldwide, including the Museum of New Zealand,[48] the Santa Barbara Museum of Art,[49] the British Museum,[50] the Museum of Modern Art,[51] the University of Michigan Museum of Art,[52] the Brooklyn Museum,[53] Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales,[54] the Detroit Institute of Arts,[55] and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[56]

Bibliography

[edit]- Augustus John, Chiaroscuro - Fragments of Autobiography, Readers Union / Jonathan Cape, London, 1954.

- Augustus John, Finishing Touches, edited and introduced by Daniel George, Readers Union / Jonathan Cape, London 1966.

- Michael Holroyd, Augustus John: A Biography, London: Heinemann, 1974-1975 (2 vols.); New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975 (1 vol.).

- Michael Holroyd, Augustus John: The New Biography, London, UK: Chatto & Windus, 1996; New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1996.

- David Boyd Haycock, Augustus John: Drawn from Life, London, UK: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2018.

- David Boyd Haycock, Brilliant Destiny: The Age of Augustus John: Drawn from Life, London, UK: Lund Humphries, 2023.

See also

[edit]- Vernon Watkins

- Marchesa Casati – Augustus John painting of Luisa Casati

References

[edit]- ^ Virginia Woolf, Moments of Being: Autobiographical Writings, edited by Jeanne Schulkind, London: Pimlico (2002), p. 56.

- ^ a b c "Wales arts: Augustus John". BBC Wales. 10 January 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Wintle, Justin (26 June 2002). Makers of Modern Culture. Psychology Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780415265836 – via Google Books.

- ^ Easton, Malcolm, and Holroyd, Michael: The Art of Augustus John, page 1. David R. Godine, 1975.

- ^ As witness "The legendary Slade acclamation, 'There was a man sent from God, whose name was John'". Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ One of "a bevy of talented girls" there at the time. Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ a b "Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea Pages 102-106 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". British History Online. Victoria County History, 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 2.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 13.

- ^ Cole, Dani. "The last bohemian, enthralled by Liverpool". www.livpost.co.uk.

- ^ Davies, Lynn (2025). Derwent Lees : Art and Life. London, UK: Lund Humphries. ISBN 9781848227118.

- ^ "BBC Four - The Mountain That Had to Be Painted". BBC.

- ^ In Search of Alderney Manor, Poole Museum Society

- ^ Hammill, Faye. Women, Celebrity, and Literary Culture between the Wars (2009), p. 144

- ^ Violet Powell. The Constant Novelist: a study of Margaret Kennedy, 1896-1967 (1983), pp. 57-68

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 64.

- ^ "'The Little Railway, Martigues', Augustus John OM, 1928". Tate.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 184.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 12–13.

- ^ "The University of Liverpool ~ SC&A; ~ Home". Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Holroyd, Michael (1996) Augustus John. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 432. ISBN 9780374102555.

- ^ Ltd, Not Panicking (18 September 2001). "h2g2 - 'Woman Smiling' - the Painting by Augustus John - Edited Entry". h2g2.com.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 26, 162.

- ^ "Duke and Duchess of Cambridge will unveil the Canadians Opposite Lens, the latest Canadian War Museum acquisition Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine", press release via Canada NewsWire, 2 July 2011.

- ^ James Joyce complained that John's drawings of him "failed to represent accurately the lower part of his face", and commenting on Lady Ottoline Morrell's determination to hang her portrait in her drawing-room, John observed "Whatever she may have lacked, it wasn't courage." Easton and Holroyd, pages 186, 82.

- ^ "Cailtin Thomas". BBC. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: August-September 2018". Apollo Magazine. 3 October 2018.

- ^ Thackrah, John Richard (1981). The University and Colleges of Oxford. Dalton. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-86138-002-2.

- ^ Baker, John Norman Leonard (1971). Jesus College, Oxford, 1571-1971. Jesus College, Oxford. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-9502164-0-9.

- ^ T. E. Lawrence Symposium Proceedings: A Collection of the Presentations Made at the T. E. Lawrence Symposium, Held May 20-21, 1988, at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Thomas Edward Lawrence, the Man and Legend Known as Lawrence of Arabia. Pepperdine University. 1988.

- ^ "TE Lawrence - Jesus College TE Lawrence or Lawrence of Arabia". Jesus College. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 24.

- ^ The Two Jamaican Girls, by Augustus John (1878–1961)

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 194.

- ^ Montgomery, Bernard Law (1958). The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Montgomery. London: The Companion Book Club (Oldhams Press Ltd). pp. 216–217.

- ^ Easton and Holroyd, page 156.

- ^ Hill, Rosemary (28 June 2017). "Rosemary Hill · One's Self-Washed Drawers: Ida John · LRB 28 June 2017". London Review of Books. 39 (13).

- ^ "Obituary: Vivien John". The Independent. 27 May 1994.

- ^ Gwyneth Johnstone obituary (The Guardian, 6 January 2011).

- ^ Devine, Darren (9 March 2012). "Last illegitimate son of Augustus John on life with 'King of Bohemia'". walesonline.

- ^ https://vimeo.com/465553412.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Easton and Holroyd, pages 41–2.

- ^ Augustus John; Malcolm Easton; University of Hull (1970). Augustus John: portraits of the artist's family. University of Hull. p. 11. ISBN 9780900480898.

- ^ "Gwen John and Augustus John – Exhibition at Tate Britain". Tate. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Augustus John Artist Receives Freedom Borough His Editorial Stock Photo - Stock Image | Shutterstock". Shutterstock Editorial.

- ^ Haycock (2018), p. 11.

- ^ Brooks, Richard (21 April 2024). "'Most paintings should have been burnt': Augustus John's granddaughter attacks artist's later works". The Observer.

- ^ "Loading... | Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Augustus JOHN - Artists - eMuseum". collections.sbma.net. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "drawing | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Augustus John. Alice Rothenstein. (n.d.) | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Exchange: William Butler Yeats". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Art Collections Online". Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "The Mumpers". www.dia.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Collections Object : Hope Scott". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=HTbdQpasheY Lyric: Remember this oil by Augustus John?

External links

[edit]- 288 artworks by or after Augustus John at the Art UK site

- Augustus John collection at the Tate Gallery Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Augustus John collection at the National Portrait Gallery London Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Augustus John collection at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

- The Dawn a symbolic war lithograph of 1917

- Augustus John - an appreciation by Colin Ward

- John's prize-winning painting Study for Moses and the Brazen Serpent

- Portraits of Elizabeth Asquith by John and others

- John's sketch of the writer, James Joyce

- John's connection with the anarchist movement from libcom.org

- Augustus John's Collection Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

- 1878 births

- 1961 deaths

- 19th-century Welsh painters

- 19th-century Welsh male artists

- 20th-century British printmakers

- 20th-century Welsh painters

- 20th-century Welsh male artists

- Academics of the University of Liverpool

- Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art

- British pacifists

- British portrait painters

- British war artists

- Canadian Expeditionary Force officers

- John family

- Members of the Order of Merit

- People from Tenby

- Post-impressionist painters

- Royal Academicians

- Royal Society of Portrait Painters

- Sibling artists

- Welsh etchers

- Welsh male painters

- Welsh people of English descent

- World War I artists

- Military personnel from Pembrokeshire