Joaquín Ascaso

Joaquín Ascaso | |

|---|---|

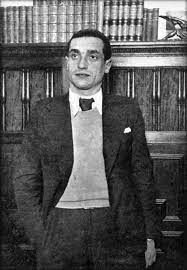

Joaquín Ascaso (January 1937) | |

| President of the Regional Defence Council of Aragon | |

| In office 6 October 1936 – 11 August 1937 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joaquín Ascaso Budría 5 June 1906 Zaragoza, Spain |

| Died | 12 March 1977 (aged 70) Caracas, Venezuela |

| Nationality | Aragonese |

| Political party | Confederación Nacional del Trabajo |

| Profession | Construction worker |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1936–1938 |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Spanish Civil War |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcho-syndicalism |

|---|

|

Joaquín Ascaso Budría (5 June 1906 – 12 March 1977) was an Aragonese anarcho-syndicalist and President of the Regional Defence Council of Aragon between 1936 and 1937.

An anarcho-syndicalist activist from an early age, he led the construction workers' union of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) in Zaragoza during the time of the Second Spanish Republic. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he resisted the military uprising in Barcelona before returning to Aragon to fight on the front. There he participated in the creation of the Regional Defence Council and was elected as its president.

Facing political repression by the central government, he attempted to seek formal recognition and support from them, but attracted the ire of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE). In the wake of the May Days, the Regional Council was liquidated by the government and Ascaso was arrested on charges of corruption, but no evidence of such was found. He returned to the Aragon front, but after the Aragon Offensive led to the region's capture by the Nationalists, he decided to flee into exile. After years in French prisons, he emigrated to Venezuela, where he spent the rest of his life.

Biography

[edit]Early life and activism

[edit]On 5 June 1906, Joaquín Ascaso was born into a working-class family in the Torrero neighbourhood of Zaragoza.[1] He grew up in the Aragonese capital, where he joined the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) while he was still a teenager.[2]

During the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, he was imprisoned and later fled into exile in France. Following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, he returned to Zaragoza,[3] where he became leader of the CNT's construction workers' union[4] and led efforts to organize unemployed workers.[5] Together with Miguel Abós Serena, in November 1932, he led a strike that secured a forty-four hour work week for construction workers. In February 1933, he was arrested for his subversive activities and imprisoned, spending months between different prisons in Zaragoza and Burgos.[1]

In November 1933, he was elected as secretary of the CNT's national committee,[3] and the following month, he participated in an anarchist insurrection.[6] As the years went by, Ascaso was increasingly criticised by other members of the Aragonese CNT,[1] but still attended the organisation's Zaragoza Congress in May 1936.[7]

Ascaso then moved to Barcelona, where he fought against the military uprising as part of the Durruti Column.[1] On 19 July 1936, his cousin Francisco Ascaso was killed during the fighting.[8] On 23 July, members of the anarchist group Nosotros, including Ascaso, met at the militia committee headquarters. There, Joan Garcia i Oliver proposed that the militias seize control of Barcelona's government buildings and proclaim libertarian communism. But this was proposed by Buenaventura Durruti, who instead prioritised the capture of Zaragoza and the establishment of anarchist control over Aragón.[9] Ascaso himself then joined up with the Ortiz Column, with which he returned to Aragon, capturing Bujaraloz and then Caspe.[1]

President of Aragon

[edit]In October 1936, a conference of delegates from the confederal militias and agrarian collectives in Bujaraloz resolved to establish the Regional Defense Council of Aragon.[10] Ascaso was elected as president of the new Council,[11] which initially consisted entirely of members of the CNT-FAI.[12] Ascaso claimed that the council had been established from the free election of local committees, but this was disputed by historian Walther Bernecker, who instead insisted that it was entirely the work of the militia leaders, without even the agreement of the CNT.[13]

As the council was still only a de facto regime, with not even the CNT itself having approved of its creation, Benito Pabón recommended that they seek official recognition from the Republican government.[14] In November 1936, Pabón formed a delegation, together with Ascaso and Miguel Chueca,[15] which went to meet with Republican government officials in Madrid.[16] Prime minister Francisco Largo Caballero offered to recognise the autonomous regional organization, on the condition that they allow the participation of political parties.[17]

By December 1936, the government's recognition of the council was made official,[18] with civil and military functions being delegated to it and Ascaso himself being named governor-general of Aragon.[19] The council was reorganized to bring in representatives from the political parties,[20] but Ascaso remained in place as its president.[21] One of the first issues brought to the new council was law and order. Ascaso expressed a desire to dissolve the existing control patrols, but as the government could not send law enforcement to the region at that time, he resolved to employ 1,000 public order agents, half from the CNT and the other half from the political parties.[22]

Before long, the Council of Aragon was already facing pressure from advocates of centralisation, who resented its autonomy from the government.[23] In the wake of the May Days, the Council of Aragon came under attack by the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the Republican Left (IR), with President Azaña ordering the new prime minister Juan Negrín to liquidate it.[24] On 22 May 1937, the Communists met with Ascaso and attempted to propose the council's restructuring, but this was rejected, as the council was considered to represent the "popular will" of the Aragonese people.[25] After the Battle of Brunete, the communists began to accuse Ascaso of "acting like a Mafia chieftain" and of smuggling jewellery out of Spain, a charge against which he was defended by Aragonese anarchists.[26]

On 19 July 1937, the first anniversary of the Spanish Revolution, Ascaso attempted to defend the Council in a speech on Caspe radio.[27] He emphasised that the people of Aragon had been abandoned by the government in the wake of the military coup and that they had consequently built their own institutions, including the rural collectives, for which he reserved particular praise.[28] He characterised the council as "the child of the Revolution" and claimed that those that sought to liquidate it were in fact attempting to put an end to the Revolution.[29] He cited a pact by the Popular Front, which had defined the council's jurisdiction to intensify agricultural production and repress any fascists in the region.[30] He concluded by expressing his confidence in the Republican government to respect the will of the Aragonese people.[31]

Repression and exile

[edit]Despite the pleas of the anarchists, the Negrín government charged Communist military commander Enrique Lister with liquidating the council.[32] On 11 August 1937, Negrín decreeded the dissolution of the Council[33] and the deposition of Ascaso as governor-general of Aragon, replacing him with the communist José Ignacio Mantecón.[34] The decree signalled Lister's 11th Division,[35] along with the 27th and 30th Divisions,[36] to invade Aragon, break up the agrarian collectives and arrest the anarchists en masse.[37]

After the council was liquidated, Ascaso was arrested on charges of corruption, accused by the Communists of having used his position to accumulate private property.[38] He was taken to the Republican capital of Valencia,[39] where the communists attempted to arrange a show trial for Ascaso,[26] but they were ultimately unable to substantiate any of the charges against him.[40] He was released from prison on 18 September 1937,[41] without charge.[42] Three decades later, Dolores Ibárruri would attempt to revive the accusations against Ascaso, claiming that he was living in luxury in South America off his stolen loot.[26]

He then returned to Barcelona and joined the 24th Division of the Spanish Republican Army, under the command of Antonio Ortiz Ramírez. Following the Nationalist victory in the Aragon Offensive, on 5 July 1938, Ascaso and other members of the division fled to France.[1] In September 1938, he was expelled from the CNT by order of the national committee,[43] having been denounced as "quixotic" by the secretary general Mariano R. Vázquez.[44]

He lived clandestinely in Paris until the Nazi occupation of France, following which he was arrested and imprisoned in Marseilles for seven years. In 1947, he and his French partner Gisèle emigrated to Caracas, Venezuela, where they had two children.[1] Ascaso spent his final years working as a concierge in a hotel,[45] dying in poverty on 12 March 1977.[1]

Recognition

[edit]

By decision of the Zaragoza City Council, in compliance with Spain's Historical Memory Law, on 17 February 2009,[46] the Torrero neighbourhood of Zaragoza had a street named after him. This replaced "Cinco de Noviembre", which was previously named after the victims of the Republican bombing of the arms depot in the neighbourhood.[47] There is also a monument to him in Torrero, in front of the local civic centre.[48]

See also

[edit]- 11th Division

- Domingo Ascaso Abadía (cousin)

- Francisco Ascaso (cousin)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 806.

- ^ a b Alexander 1999, p. 806; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 806; Casanova 2004, pp. 48, 56; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 806; Casanova 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 806; Casanova 2004, p. 74.

- ^ Casanova 2004, p. 95; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 806; Beevor 2006, pp. 70, 113.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 744.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 803–805; Beevor 2006, p. 113; Casanova 2004, p. 127; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 805–806; Beevor 2006, p. 113; Casanova 2004, p. 127; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 805–806; Peirats 1998, p. 249.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 818–819.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 809.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 810.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 810; Beevor 2006, p. 147; Casanova 2004, p. 128; Peirats 1998, p. 250.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 810; Casanova 2004, p. 128.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 811; Casanova 2004, p. 128; Peirats 1998, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 811; Casanova 2004, p. 128.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 811–812; Beevor 2006, p. 147; Peirats 1998, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 811–812; Casanova 2004, p. 128.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 813.

- ^ Beevor 2006, p. 147.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 820–821.

- ^ Casanova 2004, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Beevor 2006, p. 295.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 822.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 822–823.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 823.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 823–824.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 824.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 825–826.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 827; Beevor 2006, p. 295; Casanova 2004, pp. 134, 154.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 827; Casanova 2004, p. 154.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 827–828; Beevor 2006, p. 295; Casanova 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 827–828; Beevor 2006, p. 295.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 827–828; Beevor 2006, p. 295; Casanova 2004, pp. 134, 154.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 817–818; Casanova 2004, p. 154; Peirats 1998, p. 254.

- ^ Casanova 2004, p. 154; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, p. 828; Beevor 2006, p. 295; Peirats 1998, p. 254.

- ^ Beevor 2006, p. 295; Casanova 2004, p. 154; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ Alexander 1999, pp. 817–818; Peirats 1998, p. 254.

- ^ Casanova 2004, p. 154.

- ^ Peirats 1998, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Beevor 2006, p. 295; Díez Torre 2018.

- ^ "Los nuevos nombres de las calles afectadas por la Ley de Memoria Histórica convivirán con el actual durante dos años". Zaragoza City Council (in Spanish). 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Soria, Celia (30 March 2009). "Una calle con tradición anarquista". El Periódico de Aragón (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Homenaje a Joaquín Ascaso en Zaragoza". Zaragoza City Council (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alexander, Robert J. (1999). Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War. Vol. 2. Janus Publishing. ISBN 1-85756-412-X.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297848321.

- Bolloten, Burnet (1991). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1906-9. LCCN 89-77911.

- Casanova, Julian (2004) [1997]. Anarchism, the Republic and Civil War in Spain: 1931–1939. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-02280-7.

- Díez Torre, Alejandro R. (2018). "Joaquín Ascaso Budría". Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Peirats, Josep (1998). Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution. Freedom Press. ISBN 0-900384-53-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Ascaso, Joaquín (2006). Memorias (1936-1938): Hacia un nuevo Aragón (in Spanish). Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza. ISBN 9781441666406. OCLC 656283997.

- Carrasquer Launed, Francisco (2003). Ascaso y Zaragoza, dos pérdidas: La pérdida (in Spanish). Alcaraván Ediciones. ISBN 9788495222060. OCLC 469337608.

- Castro, A. (6 June 2006). "Joaquín Ascaso : historia y exilio de un anarquista que lo perdió todo". Heraldo de Aragón (in Spanish) – via Rojo y Negro.

- Gómez Casas, Juan (1977). Los anarquistas en el gobierno, 1936-1939 (in Spanish). Editorial Brugera. ISBN 9788402051738. OCLC 802017888.

- Martín Soriano, Augusto (2015). Libertarios de Aragón: Cronología en torno a Joaquín Ascaso, el Consejo de Aragón y los anarquistas de nuestra tierra (in Spanish). Doce Robles. ISBN 978-84-941586-6-7. OCLC 970409652.

- Salvador Paz, Borja (7 April 2014). "Guerra y Revolución: Joaquín Ascaso, el primer presidente aragonés y El Consejo de Aragón". Regeneración (in Spanish).

- "Ascaso Budría, Joaquín". Memoria Libertaria (in Spanish). CGT. 28 March 2014.

- 1906 births

- 1977 deaths

- Anarchists from Aragon

- Confederación Nacional del Trabajo members

- Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in France

- Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in Venezuela

- People from Zaragoza

- Politicians from Aragon

- Prisoners and detainees of Spain

- Prisoners and detainees of Vichy France

- Spanish emigrants to Venezuela

- Spanish military personnel of the Spanish Civil War (Republican faction)

- Spanish trade union leaders