Luther Vandross

Luther Vandross | |

|---|---|

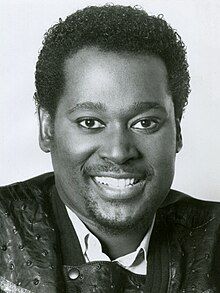

Vandross in 1985 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Luther Ronzoni Vandross Jr. |

| Born | April 20, 1951 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 2005 (aged 54) Edison, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1969–2004 |

| Labels | |

| Website | luthervandross |

Luther Ronzoni Vandross Jr. (April 20, 1951 – July 1, 2005) was an American soul and R&B singer, songwriter, and record producer. Throughout his career, he achieved eleven consecutive RIAA-certified platinum albums and sold over 40 million records worldwide.[1] Known as the "Velvet Voice", Vandross has been recognized as one of the 200 greatest singers of all time (2023) by Rolling Stone,[2] as well as one of the greatest R&B artists by Billboard.[3] NPR additionally named him one of the 50 Great Voices. He was the recipient of eight Grammy Awards,[4] including Song of the Year in 2004 for a track recorded shortly before his death, "Dance with My Father".[5] In 2021, he was posthumously inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Vandross worked as a backing vocalist in the 1970s, and appeared on albums by artists such as Roberta Flack, Donny Hathaway, Todd Rundgren, Evelyn "Champagne" King, Judy Collins, Chaka Khan, Bette Midler, Diana Ross, David Bowie, Ben E. King, Stevie Wonder, and Donna Summer. He later became a lead singer of the group Change, which released the Gold-certified album, The Glow of Love, in 1980 on Warner/RFC Records. After Vandross left the group, he was signed to Epic Records as a solo artist and released his debut solo album, Never Too Much, in 1981.

His hit songs include "Never Too Much", "Here and Now", "Any Love", "Power of Love/Love Power", "I Can Make It Better", and "For You to Love". Many of his songs were covers of original music by other artists such as "If This World Were Mine" (duet with Cheryl Lynn), "Since I Lost My Baby", "Superstar", "I (Who Have Nothing)", and "Always and Forever". He performed duets such as "The Closer I Get to You" with Beyoncé, "Endless Love" with Mariah Carey, and "The Best Things in Life Are Free" with Janet Jackson of which the latter two were hit songs in his career. The tribute album So Amazing: An All-Star Tribute to Luther Vandross was released shortly after his death.

Early life

[edit]Luther Ronzoni Vandross Jr.[6] was born on April 20, 1951, at Bellevue Hospital, in the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City.[7] His birth occurred concurrently with General Douglas MacArthur's ticker-tape parade throughout the same city. He was the fourth and youngest child (Anthony, Patricia, Ann)[8] as well as the second son of Mary Ida Vandross and Luther Vandross Sr.[9] His father was an upholsterer and singer,[10] and his mother was a nurse.[11] Vandross was raised in Manhattan's Lower East Side in the Alfred E. Smith Houses public housing development.[12] At the age of three, having his own phonograph, Vandross taught himself to play the piano by ear.[6]

His father died of diabetes when Vandross was eight years old.[6][12][13] In 2003, Vandross wrote the song "Dance with My Father" and dedicated it to him; the title was based on his childhood memories and his mother's recollections of the family singing and dancing in the house. His family moved to the Bronx when he was nine.[14] His sisters, Patricia "Pat" and Ann, began taking Vandross to the Apollo Theater and to a theater in Brooklyn to see Dionne Warwick and Aretha Franklin perform.[6] Patricia sang with the vocal group The Crests[15] and was featured on the songs "My Juanita" and "Sweetest One".[10][16]

Vandross graduated from William Howard Taft High School in the Bronx in 1969,[15] and attended Western Michigan University for one and a half semesters before dropping out to continue pursuing a career in music.[17]

Career

[edit]While in high school, Vandross founded the first Patti LaBelle fan club, of which he was president.[15][18] He also performed in a group, Shades of Jade, that once played at the Apollo Theater. During his early years in show business, he appeared several times at the Apollo's famous amateur night.[6][19] While he was a member of a theater workshop, Listen My Brother,[6] he was involved in the singles "Only Love Can Make a Better World" and "Listen My Brother". The group performed in front of tens of thousands at the Harlem Cultural Festival in late August 1969.[20] Directly afterward, he appeared with the group in the pilot episode and other episodes of the first season of Sesame Street during 1969–1970.[21]

1970s: Back-up vocalist and first groups

[edit]Vandross added backing vocals to Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway in 1972,[22] and worked on Delores Hall's Hall-Mark album (1973). He sang with her on the song "Who's Gonna Make It Easier for Me", which he wrote, and he contributed another song, "In This Lonely Hour".[citation needed] After his song "Funky Music (Is a Part of Me)" was re-written as "Fascination" with David Bowie for the latter's Young Americans (1975) album, Vandross went on to tour with him as a back-up vocalist in September 1974.[23] Vandross wrote "Everybody Rejoice/A Brand New Day" for the 1975 Broadway musical The Wiz.[10][17][24]

Vandross also sang backing vocals for artists, including Roberta Flack,[10] Chaka Khan, Ben E. King, Bette Midler, Diana Ross, Carly Simon, Barbra Streisand, David Bowie, Cat Stevens, Gary Glitter, Ringo Starr, Sister Sledge, and Donna Summer,[25][26] and for the bands Mandrill, Chic[24] and Todd Rundgren's Utopia.[27]

Before his solo breakthrough, Vandross was part of a singing quintet named Luther in the late 1970s. The quintet consisted of former Shades of Jade members Anthony Hinton and Diane Sumler, as well as Theresa V. Reed, and Christine Wiltshire, signed to Cotillion Records. Although the singles "It's Good for the Soul", "Funky Music (Is a Part of Me)",[24] and "The Second Time Around" were relatively successful, their two albums, the self-titled Luther (1976) and This Close to You (1977), which Vandross produced, did not sell enough to make the charts. Vandross bought back the rights to those albums after Cotillion dropped the group, preventing them from being re-released.[28] Both albums were re-released in 2024.[29]

Vandross also wrote and sang commercial jingles from 1977 until the early 1980s, for companies including NBC, Mountain Dew, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Burger King, and Juicy Fruit.[10][12] He continued his successful career as a popular session singer during the late 1970s. His aforementioned song "Everybody Rejoice", sometimes called "A Brand New Day", was used in a Kodak commercial during the mid-1970s.[30]

In 1978, Vandross sang lead vocals for Gregg Diamond's disco band, Bionic Boogie, on the song titled "Hot Butterfly".[6] Also in 1978, he appeared on Quincy Jones's Sounds...and Stuff Like That!!, most notably on the song "I'm Gonna Miss You in the Morning" along with Patti Austin.[31] Vandross also sang with the band Soirée and was the lead vocalist on the track "You Are the Sunshine of My Life"; he also contributed background vocals to the album along with Jocelyn Brown and Sharon Redd, each of whom also saw solo success. Additionally, he sang the lead vocals on the group Mascara's LP title song "See You in L.A." released in 1979. Vandross also appeared on the group Charme's 1979 album Let It In.[citation needed]

1980s: Change and solo breakthrough

[edit]

Vandross made his career breakthrough as a featured singer with the vaunted pop-dance act Change, a studio concept created by French-Italian businessman Jacques Fred Petrus. Their 1980 hits, "The Glow of Love" (by Romani, Malavasi and Garfield) and "Searching" (by Malavasi), featured Vandross as the lead singer. In a 2001 interview with Vibe, Vandross said "The Glow of Love" was "the most beautiful song I've ever sung in my life."[15] Both songs were from Change's debut album, The Glow of Love.

Vandross was originally intended to perform on their second and highly successful album Miracles in 1981, but declined the offer as Petrus didn't pay enough money. Vandross's decision led to a recording contract with Epic Records that same year,[10] but he also provided background vocals on "Miracles" and on the new Petrus-created act, the B. B. & Q. Band in 1981. During that year, Vandross jump-started his second attempt at a solo career with his debut album, Never Too Much. In addition to the hit title track it contained a version of the Bacharach & David song "A House Is Not a Home".[10]

The song "Never Too Much", written by Vandross, reached number-one on the R&B charts. This period also marked the beginning of a songwriting collaboration with bassist Marcus Miller, who played on many of the tracks and would also produce or co-produce a number of tracks for Vandross. The Never Too Much album was arranged by Vandross's high school classmate, Nat Adderley Jr., a collaboration that would last throughout Vandross's career.[32]

Vandross released a series of successful R&B albums during the 1980s and continued his session work with guest vocals on groups like Charme in 1982. Many of his earlier albums made a bigger impact on the R&B charts than on the pop charts. During the 1980s, two of Vandross's singles reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B charts: "Stop to Love", in 1986, and a duet with Gregory Hines, "There's Nothing Better Than Love."[33] Vandross was at the helm as producer for Aretha Franklin's Gold-certified, award-winning comeback album Jump to It.[34] He also produced its follow-up album, 1983's Get It Right.[10][35]

In 1983, the opportunity to work with his main musical influence, Dionne Warwick, came about with Vandross producing, writing songs, and singing on How Many Times Can We Say Goodbye, her fourth album for Arista Records.[10][36] The title track duet reached No. 27 on the Hot 100 chart (#7 R&B/#4 Adult Contemporary),[37] while the second single, "Got a Date" was a moderate hit (#45 R&B/#15 Club Play).

Vandross wrote and produced "It's Hard for Me to Say" for Diana Ross from her Red Hot Rhythm & Blues album.[38] Ross performed the song as an a cappella tribute to Oprah Winfrey on her final season of The Oprah Winfrey Show. She then proceeded to add it to her successful 2010–12 "More Today Than Yesterday: The Greatest Hits Tour. Vandross also recorded a version of this song on his Your Secret Love album in 1996.

In 1985, Vandross first spotted the talent of Jimmy Salvemini, who was 15 at the time, on Star Search. He thought Salvemini had the perfect voice for some of his songs and contacted him. He was managed by his brother, Larry Salvemini. A contract was negotiated with Elektra Records for $250,000 and Vandross agreed to produce the album. He contacted his old friends – Cheryl Lynn, Alfa Anderson (of Chic), Phoebe Snow and Irene Cara – to appear on the record. Jimmy Salvemini's album, Roll It, was released in 1986.

Vandross also sang the ad-libs and background vocals, along with Syreeta Wright and Philip Bailey, in Stevie Wonder's 1985 hit "Part-Time Lover".[39] In 1984, he voiced a cartoon character named Zack for ABC's Zack of All Trades, a three Saturday morning animated PSA spots.[40]

The 1989 compilation album The Best of Luther Vandross... The Best of Love included the ballad "Here and Now", his first single to chart in the Billboard pop chart top ten, peaking at number six.

1990s

[edit]In 1990, Vandross wrote, produced and sang background for Whitney Houston in a song titled "Who Do You Love" which appeared on her album I'm Your Baby Tonight.[41] That year, he guest starred on the television sitcom 227.[10][42]

More albums followed in the 1990s, beginning with 1991's Power of Love which spawned two top ten pop hits. He won his first Grammy award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance in 1991.[43] He won his second Best Male R&B Vocal in the Grammy Awards of 1992, and his track "Power of Love/Love Power" won the Grammy Award for Best R&B Song in the same year. In 1992, "The Best Things in Life Are Free", a duet with Janet Jackson from the movie Mo' Money became a hit.[10] In 1993, he had a brief non-speaking role in the Robert Townsend movie The Meteor Man.[44] He played a hit man who plotted to stop Townsend's title character.[42]

Vandross hit the top ten again in 1994, teaming with Mariah Carey on a cover version of Lionel Richie and Diana Ross's duet "Endless Love".[45] It was included on the album Songs, a collection of songs that had inspired Vandross over the years. He also appears on "The Lady Is a Tramp" released on Frank Sinatra's Duets album. At the Grammy Awards of 1997, he won his third Best Male R&B Vocal for the track "Your Secret Love".

A second greatest hits album, released in 1997, compiled most of his 1990s hits and was his final album released through Epic Records. After releasing I Know on Virgin Records, he signed with J Records.[46] His first album on Clive Davis's new label, titled Luther Vandross, was released in 2001, and it produced the hits "Take You Out" (#7 R&B/#26 Pop), and "I'd Rather" (#17 Adult Contemporary/#40 R&B/#83 Pop). Vandross scored at least one top 10 R&B hit every year from 1981 to 1994.

In 1997, Vandross sang the American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner", during Super Bowl XXXI at the Louisiana Superdome, New Orleans, Louisiana.

2000s

[edit]

He made two public appearances at Diana Ross's Return to Love Tour: at its opening in Philadelphia at First Union Spectrum and its final stop at Madison Square Garden on July 6, 2000.[47]

In September 2001, Vandross performed a rendition of Michael Jackson's hit song "Man in the Mirror" at Jackson's 30th Anniversary special, alongside Usher and 98 Degrees.

In the spring of 2003, Vandross's last collaboration was Doc Powell's song "What's Going On", a cover of Marvin Gaye's seminal 1971 original, from Powell's album 97th and Columbus.

In 2003, Vandross released the album Dance with My Father. It sold 442,000 copies in the first week and debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 album chart.[48][49] The title track of the same name, which was dedicated to Vandross's childhood memories of dancing with his father, won Vandross and his co-writer, Richard Marx, the 2004 Grammy Award for Song of the Year.[10] The song also won Vandross his fourth and final award in the Best Male R&B Vocal Performance category.[10] The album was his only career No. 1 on the Billboard album chart. The video for the title track features various celebrities alongside their fathers and other family members.[50] The second single released from the album, "Think About You", was the number one Urban Adult Contemporary Song of 2004 according to Radio & Records.

In 2003, after the televised NCAA Men's Basketball championship, CBS Sports gave "One Shining Moment" a new look. Vandross, who had been to only one basketball game in his life, was the new singer, and the video had none of the special effects, like glowing basketballs and star trails, that videos from previous years had. This song version is in use today.[51]

Posthumous releases

[edit]J Records released a song in 2006, "Shine" – an upbeat R&B track that samples Chic's disco song "My Forbidden Lover" – which reached No. 31 on the Billboard R&B chart.[52] The song was originally slated to be released on the soundtrack to the movie, The Fighting Temptations, but it was shelved. A later remix of the song peaked at No. 10 on the Club Play chart.[citation needed] "Shine" and a track titled "Got You Home" were previously unreleased songs on The Ultimate Luther Vandross (2006), a greatest hits album on Epic Records/J Records/Legacy Recordings that was released August 22, 2006.[53]

On October 16, 2007, Epic Records/J Records/Legacy Recordings released a 4-disc boxed set titled Love, Luther. It features nearly all of Vandross's R&B and pop hits throughout his career, as well as unreleased live tracks, alternate versions, and outtakes from sessions that Vandross recorded. The set also includes "There's Only You", a version of which had originally appeared on the soundtrack to the 1987 film Made in Heaven.[54][55]

In October 2015, Sony Music released a re-configured edition of its The Essential Luther Vandross compilation containing three unreleased songs: "Love It, Love It" (which made its premiere a year prior on the UK compilation The Greatest Hits), a live recording of "Bridge Over Troubled Water" with Paul Simon and Jennifer Holliday, and a cover of Astrud Gilberto's "Look to the Rainbow".[56]

Personal life

[edit]Vandross never married and had no children.[57] His mother outlived all of her four children, and his three elder siblings along with his father all predeceased him[58] due to diabetes and asthma.[59]

Sexual orientation

[edit]In 2006, Bruce Vilanch, a friend and colleague of Vandross, told Out magazine, "He said to me, 'No one knows I'm in the life.' ... He had very few sexual contacts". According to Vilanch, Vandross experienced his longest romantic relationship with a man while living in Los Angeles during the late 1980s and early 1990s.[60] In December 2017, 12 years after his death, Vandross' friend Patti LaBelle confirmed that he was gay.[61] In addition, Vandross was well aware that officially coming out as gay while he was actively making music would have been detrimental to the trajectory of his career, given the majority of his target audience were women seeking some mode of emotional engagement from his words. LaBelle said "[Vandross] had a lot of lady fans" and "he just didn't want to upset the world".[62]

In December 1985, Vandross filed a libel suit against a British magazine after it attributed his 85-pound weight loss to AIDS. He weighed 325 pounds (147 kg) when he started a diet in May of that year.[63]

1986 car accident

[edit]After signing Jimmy Salvemini and having completed his debut album Roll It, Vandross, Salvemini, and Salvemini's brother and manager Larry decided to celebrate. On January 12, 1986, they were riding in Vandross's convertible on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, in the north section of Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles. Vandross was driving at 50 mph (80 km/h) in a 35 mph (56 km/h) zone when he veered across the double yellow center line of the two lane street, turned sideways and collided with the front of a southbound car, then swung around and hit another car head on.[63][64][65][66] Vandross and Salvemini were rushed to the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.[6][63]

Larry Salvemini, who was in the passenger seat, was killed in the collision. Vandross suffered three broken ribs, a broken hip, several bruises and facial cuts.[6][63] Jimmy Salvemini, who was in the back of the car, had cuts, bruises and contusions. Vandross faced vehicular manslaughter charges as a result of Larry's death, and his driving license was suspended for a year. There was no evidence that Vandross was under the influence of alcohol or other drugs; he pleaded no contest to reckless driving. At first, the Salvemini family was supportive of Vandross, but later filed a wrongful death suit against him. The case was settled out of court with a payment to the Salvemini family of about $630,000.[67] Roll It was released later that year.

Health problems and death

[edit]Vandross had diabetes and hypertension.[17][68] On April 16, 2003, he had a severe stroke at his home in New York City[17] and was in a coma for nearly two months.[69] The stroke affected his ability to speak and sing and caused him to require a wheelchair.[70] He later regained the ability to walk.[71]

At the 2004 Grammy Awards, Vandross appeared in a pre-taped video segment to accept his Song of the Year Award for "Dance With My Father", saying, "When I say good-bye, it's never for long, because I believe in the power of love" (Vandross sang the last six words).[17] His mother, Mary, accepted the award in person on his behalf. His last public appearance was on May 6, 2004, on The Oprah Winfrey Show.[17] Vandross died on July 1, 2005, at the JFK Medical Center in Edison, New Jersey, at the age of 54 due to complications of a stroke.[68]

Vandross's funeral was held at Riverside Church in New York City on July 8, 2005.[72] Aretha Franklin, Patti LaBelle, Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick and Cissy Houston were among the speakers and singers at the service.[72][73] Vandross was entombed at George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, New Jersey.[74]

Artistry

[edit]Possessing a tenor vocal range,[11][17][75][76] Vandross was commonly referred to as "The Velvet Voice", and was sometimes called "The Best Voice of a Generation". He was also regarded as the "Pavarotti of Pop" by many critics.[77]

Legacy

[edit]Vandross has been cited as an inspiration by a number of other artists, including 112, Boyz II Men, D'Angelo, Hootie & the Blowfish, Jaheim, John Legend, Mint Condition, Ne-Yo, Ruben Studdard, and Usher.[78][79] Stokley Williams, the lead singer of Mint Condition, has said that he has "studied Luther for such a long time because he was the epitome of perfect tone." On his influence, John Legend has said, "All us people making slow jams now, we was inspired by the slow jams Luther Vandross was making."

In 2008, Vandross was ranked No. 54 on Rolling Stone magazine's List of 100 Greatest Singers of All Time. Mariah Carey stated in several interviews that standing next to Vandross while recording their duet "Endless Love" was intimidating.[80] In 2010, NPR included Vandross in its 50 Greatest Voices in recorded history, saying Vandross represents "the platinum standard for R&B song stylings." The announcement was made on NPR's All Things Considered on November 29, 2010.[81]

Tribute

[edit]In 1999, Whitney Houston sang Vandross' "So Amazing" as a tribute to Vandross as he sat in the audience during the Soul Train Awards. Johnny Gill, El DeBarge, and Kenny Lattimore provided background vocals. On July 27, 2004, GRP Records released a smooth jazz various artists tribute album, Forever, for Always, for Luther, including ten popular songs written by Vandross. The album featured vocal arrangements by Luther and was produced by Rex Rideout and Bud Harner. Rideout had co-authored songs, contributed arrangements and played keyboards on Vandross's final three albums. The tribute album was mixed by Ray Bardani, who recorded and mixed most of Luther's music over the years. It featured an ensemble of smooth jazz performers, many of whom had previously worked with Vandross.[82]

On September 20, 2005, the album So Amazing: An All-Star Tribute to Luther Vandross was released. The album is a collection of some of his songs performed by various artists, including Patti LaBelle, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Mary J. Blige, Usher, Fantasia, Beyoncé, Donna Summer, Alicia Keys, Elton John, Celine Dion, Wyclef Jean, Babyface, John Legend, Angie Stone, Jamie Foxx, and Teddy Pendergrass. Aretha Franklin won a Grammy for her rendition of "A House Is Not a Home", and Stevie Wonder and Beyoncé won a Grammy for their cover of "So Amazing".[citation needed]

On November 21, 2006, saxophonist Dave Koz released a follow-up to the earlier smooth jazz GRP tribute album, this time on his own Rendezvous Entertainment label, an album called Forever, for Always, for Luther Volume II, also produced by Rex Rideout and Bud Harner. Koz played on all the featured Luther Vandross tracks, which were recorded by various smooth jazz artists.[83]

On April 20, 2021, Google celebrated his 70th birthday with a Google Doodle of an animated clip that plays Vandross's song "Never Too Much".[84]

Discography

[edit]- Never Too Much (1981)

- Forever, for Always, for Love (1982)

- Busy Body (1983)[85]

- The Night I Fell in Love (1985)

- Give Me the Reason (1986)

- Any Love (1988)

- Power of Love (1991)

- Never Let Me Go (1993)

- Songs (1994)

- This Is Christmas (1995)

- Your Secret Love (1996)

- I Know (1998)

- Luther Vandross (2001)

- Dance with My Father (2003)

Tours

[edit]- Luther Tour (1981)

- Forever, for Always, for Love Tour (1982–1983)

- Busy Body Tour (1984)

- The Night I Fell in Love Tour (1985–1986)

- Give Me the Reason Tour (1987)

- The Heat (with Anita Baker) (1988)

- Any Love World Tour (1989)

- Best of Love Tour (1990)

- The Power of Love Tour (1991)

- Never Let Me Go World Tour (1993–1995)

- Your Secret Love World Tour (1997)

- Luther & Vanessa Live! (with Vanessa Williams) (1997)

- Take You Out Tour (2001–2002)

- BK Got Music Summer Soul Tour (with Gerald Levert, Angie Stone and Michelle Williams) (2002)

Awards

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Luther Vandross | Best New Artist | Nominated |

| Never Too Much | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated | |

| 1983 | Forever, For Always, For Love | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1986 | The Night I Fell in Love | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1987 | "Give Me the Reason" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| Best R&B Song (shared with Nat Adderley Jr.) | Nominated | ||

| 1989 | "Any Love" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| Best R&B Song (shared with Marcus Miller) | Nominated | ||

| 1990 | "She Won't Talk to Me" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1991 | "Here and Now" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Won |

| 1992 | "Power of Love/Love Power" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Won |

| Best R&B Song (with Marcus Miller and Teddy Vann) | Won | ||

| "Doctor's Orders" (with Aretha Franklin) | Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals | Nominated | |

| 1993 | "The Best Things in Life Are Free" (with Janet Jackson) | Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals | Nominated |

| 1994 | "How Deep Is Your Love" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| "Heaven Knows" | Best R&B Song (shared with Reed Vertelney) | Nominated | |

| "Little Miracles (Happen Every Day)" | Best R&B Song (shared with Marcus Miller) | Nominated | |

| 1995 | "Love the One You're With" | Best Male Pop Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| "Endless Love" (with Mariah Carey) | Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals | Nominated | |

| "Always and Forever" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated | |

| Songs | Best R&B Album | Nominated | |

| 1997 | "Your Secret Love" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Won |

| Best R&B Song (shared with Reed Vertelney) | Nominated | ||

| 1998 | "When You Call on Me / Baby That's When I Come Runnin'" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| 1999 | "I Know" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| I Know | Best Traditional R&B Performance | Nominated | |

| 2003 | "Any Day Now" | Best Traditional R&B Performance | Nominated |

| 2004 | "Dance with My Father" | Song of the Year (shared with Richard Marx) | Won |

| Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Won | ||

| Best R&B Song (shared with Richard Marx) | Nominated | ||

| "The Closer I Get to You" (with Beyoncé) | Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals | Won | |

| Dance with My Father | Best R&B Album | Won | |

| 2007 | "Got You Home" | Best Male R&B Vocal Performance | Nominated |

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Give Me the Reason | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Won |

| "Give Me the Reason" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Nominated | |

| 1988 | "So Amazing" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Nominated |

| 1989 | Any Love | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Nominated |

| 1990 | The Best of Luther Vandross... The Best of Love | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Nominated |

| "Here and Now" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Won | |

| Best Song of the Year | Nominated | ||

| 1992 | Power of Love | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Won |

| "Power of Love/Love Power" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Nominated | |

| 1994 | Never Let Me Go | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Nominated |

| "Heaven Knows" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Nominated | |

| 1995 | Songs | Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Nominated |

| 1999 | Luther Vandross | Quincy Jones Award for Career Achievement | Honour |

| 2004 | Dance with My Father | Best Album of the Year | Nominated |

| Best R&B/Soul Album – Male | Nominated | ||

| "Dance with My Father" | Best R&B/Soul Single – Male | Won | |

| 2005 | "The Closer I Get to You" (with Beyoncé) | Best R&B/Soul Single – Group, Band or Duo | Nominated |

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Nominated |

| The Night I Fell in Love | Favorite Soul/R&B Album | Nominated | |

| 1988 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| Give Me the Reason | Favorite Soul/R&B Album | Nominated | |

| 1990 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| 1992 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| Power of Love | Favorite Soul/R&B Album | Won | |

| 1994 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| 1996 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| 2002 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| 2003 | Luther Vandross | Favorite Soul/R&B Male Artist | Won |

| Dance with My Father | Favorite Soul/R&B Album | Won |

- Hollywood Walk of Fame

- Inducted: Star (Posthumous; June 3, 2014)[86]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Luther Vandross | Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame | Inducted |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Barker, Andrew (June 3, 2014). "Luther Vandross Receives Star on Walk of Fame". Variety. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "The 35 Greatest R&B Artists of All Time". Billboard. November 12, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ "Vandross' Funeral Soulful and Powerful". Yahoo! News. July 8, 2005. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

- ^ "Obituary: Luther Vandross". BBC News. July 1, 2005. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Walters, Barry (April 1987). "Soul God". Spin (magazine). Vol. 3, no. 1. Spin Media LLC. pp. 31–33, 97. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Seymour 2004, p. 16 cdd

- ^ "Luther Vandross' Mother Thanks Fans For Prayers; Says Singer Is Making Progress". Jet. Vol. 103, no. 21. May 19, 2003. pp. 16–17. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Luther Vandross' Mother Thanks Fans For Prayers; Says Singer Is Making Progress". Jet. Vol. 103, no. 21. May 19, 2003. pp. 16–17. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Christian, Margena A. (July 24, 2005). "Luther Vandross: R&B Superstar 1951–2005". Jet. Vol. 108, no. 4. pp. 26–38. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Cartwright, Garth (July 4, 2005). "Obituary: Luther Vandross". The Guardian. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Coombs, Orde (February 15, 1982). "The Voice of The New Vulnerability". New York. Vol. 15, no. 7. New York Media, LLC. pp. 45–49. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Luther Vandross' Mother Becomes Spokesperson For Diabetes". Jet. Vol. 105, no. 9. March 1, 2004. p. 12. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Luther Vandross Inducted into Bronx Walk of Fame". Jet. Vol. 112, no. 8. August 27, 2007. p. 32. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Seymour, Craig (September 2001). "Searching". Vibe. Vol. 9, no. 9. Vibe Media Group. pp. 166–170. ISSN 1070-4701. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ George, Lynell (July 2, 2005). "Luther Vandross, 54; 'Soul Balladeer' Sang With Eloquence and Restraint". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leeds, Jeff (July 2, 2005). "Luther Vandross, Smooth Crooner of R&B, Is Dead at 54". The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ Witchel, Alex (May 28, 2003). "Miss LaBelle's Kitchen: Hot Sauce and Gold Lamé". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Norment, Lynn (December 1991). "Love Power!". Ebony. 47 (2): 93–94, 96, 98. ISSN 0012-9011. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Porter, James (July 6, 2021). "'Are You Ready, Black People?': Summer Of Soul Takes Us Higher". Rock & Roll Globe. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "Biography". luthervandross.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "Credits". AllMusic.

- ^ "Luther Vandross Dies Aged 54". davidbowie.com. July 2, 2005. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c Grein, Paul (February 13, 1982). "Vandross Cooks Up a Storm". Billboard. Vol. 94, no. 6. pp. 6, 53. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Luther Vandross". The Daily Telegraph. July 4, 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Cartwright, Garth (July 4, 2005). "Luther Vandross Leading soul singer of the disco age". The Guardian. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Michael (April 11, 2012). "Todd Rundgren's Utopia Live At Hammersmith Odeon '75". Exclaim!. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Phil (October 23, 2011). "Barry may be the walrus of love. But Luther is the real thing". The Independent. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Facebook" – via Facebook.[user-generated source]

- ^ "Kodak Instant Camera Xmas Commercial (1976)". December 14, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony (2013). Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities. New York University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8147-6060-4. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Oshinsky, Matthew (September 10, 2009). "Born to swing: Nat Adderley Jr. returns to his roots". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ .Artist Chart History

- ^ Grien, Paul (September 4, 1982). "Arif, Aretha Back on Top; And Now, It's Miller Time". Billboard. Vol. 94, no. 34. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 6. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Bego, Mark (2010). Aretha Franklin: The Queen of Soul. Da Capo Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7867-5229-4.

- ^ Waldron, Clarence (June 17, 1985). "Luther Vandross Tells What Inspires Him As Songwriter And Entertainer". Jet. Vol. 68, no. 14. pp. 54–55. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Artist Chart History

- ^ Walters, Barry (September 1987). "Diana Ross: Red Hot Rhythm and Blues". Spin (magazine). Vol. 3, no. 6. Spin Media LLC. p. 26. ISSN 0886-3032. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ "Timeline". Luther Vandross. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "7 Creepy Saturday Morning Monsters". MTV. October 28, 2011. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Waldron, Clarence (November 5, 1990). "Whitney Houston Talks About Her Long-Awaited Album, 'I'm Your Baby Tonight'". Jet. Vol. 79, no. 4. pp. 34–36. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "People Are Talking About..." Jet. Vol. 82, no. 7. June 8, 1992. p. 61. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Bookbinder, Adam (April 21, 2014). "Luther Vandross' Top 5 Smooth R&B Songs". 94.7 The WAVE. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Robert Townsend's 'The Meteor Man' Uses Cast of Stars to Battle Drugs, Violence and Gangs". Jet. Vol. 84, no. 15. August 9, 1993. pp. 58–61. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Trust, Gary (June 3, 2014). "Mariah Carey's 25 Biggest Billboard Hits". Billboard. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Luther Vandross Signs with Clive Davis' New Label, J Records". Jet. Vol. 98, no. 20. October 23, 2000. p. 38. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Luther Vandross (1951–2005)". September 9, 2018.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (June 18, 2003). "Ailing Luther Vandross tops the album chart". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Vandross Hits Career Peak as Health Improves". Billboard. Vol. 115, no. 26. June 28, 2003. p. 71. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Vandross Video Features Famous Friends, Fans". Billboard. July 19, 2003. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ "tyrtitiiyj".

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip Hop Songs". Billboard. August 12, 2006. p. 85. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ^ "Finally". Los Angeles Times. June 20, 2006. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan (August 31, 2007). "Rare Cuts Bolster Four-Disc Vandross Box". Billboard. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna; Barnes, Ken; Jones, Steve; Mansfield, Brian; Gardner, Elysa (November 23, 2007). "A box set for every musical taste". USA Today. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Essential Luther Vandross". Amazon.com. October 16, 2015.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (July 1, 2005). "Singer Luther Vandross Dies at 54". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Luther Vandross dies at age 54". Today. Associated Press. July 2, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Luther's mother bears pain of great loss". August 31, 2006.

- ^ Weinstein, Steve (April 2006). "The Secret Gay Life of Luther Vandross". Out. pp. 60–64. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Keith Gaynor, Gerren (December 9, 2017). "The real tragedy in Patti LaBelle's outing of Luther Vandross". TheGrio.

- ^ Rita, Cynthia (September 5, 2018). "Here is the reason why Luther Vandross kept his sexuality a secret". new.amomama.com. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Police Say They'll Seek Charge Against Singer in Fatal Crash". Associated Press News. January 13, 1986. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "Passenger Dies in Crash of Car Driven by R&B Singer Vandross". Los Angeles Times. January 13, 1986. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "People in the News". Associated Press News. January 18, 1986. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "Luther Vandross Injured in Three-Car Collision; One Passenger Killed". Jet. Vol. 69, no. 19. January 27, 1986. p. 14. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "Local News in Brief: City Settles in Car Crash". Los Angeles Times. December 10, 1987. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Anderson, Brooke; Leopold, Todd (July 1, 2005). "Luther Vandross dead at 54". CNN. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ Smolowe, Jill (October 20, 2003). "Luther Sings Again". People. Vol. 60, no. 16. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (March 2, 2004). "Ailing Vandross Won't Attend Grammys". People. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Luther Vandross Continues to Improve After Stroke Two years Ago". Jet. 107 (14): 60. April 4, 2005. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Segal, David (July 8, 2005). "Soulful Sendoff For a Singer". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Phillips, Caryl (July 30, 2005). "The power of love". The Guardian. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Friends, fans mourn Luther Vandross". Today. Reuters. July 7, 2005. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Himes, Geoffrey (April 28, 1991). "Luther Vandross's Inimitable 'Power'". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ Adler, Bill (February 28, 1983). "Singer, Producer and Grammy Nominee Luther Vandross Is R & B's Heavyweight". People. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Luther Vandross". Soulmusichq.com. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Luther Vandross: Followers, MTV. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem (July 1, 2005). "Alicia Keys, Ruben Studdard, Mya Remember Luther Vandross". MTV. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "100 Greatest Singers: Luther Vandross". Rolling Stone. December 3, 2010.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (November 29, 2010). "Luther Vandross: The Velvet Voice". NPR. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Forever, For Always, For Luther, VerveMusicGroup.com

- ^ Forever, For Always, For Luther Volume II Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, smoothvibes.com

- ^ "Luther Vandross's 70th Birthday". April 20, 2021.

- ^ "The Charlotte News, 29 March 1984". The Charlotte News. March 29, 1984. p. 41. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Harvey, Kyle (May 30, 2014). "Luther Vandross to receive star on Hollywood's walk of fame". The Grio. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- General sources

- Seymour, Craig (2004). Luther: The Life and Longing of Luther Vandross. New York: HarperEntertainment. ISBN 0-06-059418-7. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- Vandross, Luther (1990). The Best of Luther Vandross: The Best of Love. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-7935-0291-8.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Remembering Luther Vandross Archived June 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Luther Vandross at AllMusic

- "Luther Vandross". SoulMusic.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009

- Luther Vandross at IMDb

- Luther Vandross at Find a Grave

- Luther Vandross

- 1951 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- 21st-century American LGBTQ people

- African-American LGBTQ people

- African-American male singers

- African-American record producers

- African-American songwriters

- American ballad musicians

- American crooners

- American gay musicians

- American gay writers

- American LGBTQ singers

- American LGBTQ songwriters

- American male pop singers

- American male singers

- American rhythm and blues singers

- American soul singers

- American tenors

- Burials at George Washington Memorial Park (Paramus, New Jersey)

- Change (band) members

- Chic (band) members

- Epic Records artists

- Gay singers

- Gay songwriters

- Grammy Award winners

- J Records artists

- LGBTQ people from New York (state)

- LGBTQ record producers

- Musicians from the Bronx

- People from the Lower East Side

- People with disorders of consciousness

- Record producers from New York (state)

- Singers from New York City

- Songwriters from New York (state)

- Virgin Records artists

- Western Michigan University alumni