Self-hating Jew

The terms "self-hating Jew", "self-loathing Jew", and "auto-antisemite" (Hebrew: אוטואנטישמי, romanized: oto'antishémi, feminine: אוטואנטישמית, romanized: oto'antishémit) are pejorative terms used to describe Jewish people whose viewpoints, especially favoring Jewish assimilation, Jewish secularism, limousine liberalism, or anti-Judaism are perceived as reflecting self-hatred.[1][2]

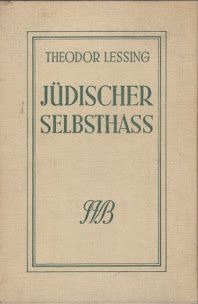

Recognition of the concept gained widespread currency after German-Jewish philosopher Theodor Lessing published his 1930 book Der jüdische Selbsthaß (lit. 'Jewish Self-Hatred'), which sought to explain a perceived inclination among secular Jewish intellectuals towards inciting antisemitism by denouncing Judaism. More recently, this spotlight on antisemitism motivated by self-hatred within the Jewish diaspora is said to have become "something of a key term of opprobrium in and beyond Cold War–era debates about Zionism" in light of how some Jews may despise their entire identity due to their perception of the Arab–Israeli conflict.[2]

Descriptions of the concept

[edit]The expression "self-hating Jew" is often used rhetorically, meaning towards Jews who differ in their lifestyles, interests or political positions from the speaker.[3]

- Usage of self-hatred can also designate dislike, or hatred, of a group to which one belongs. The term has a long history in debates over the role of Israel in Jewish identity, where it is used against Jewish critics of Israeli government policy.[3]

- Alvin H. Rosenfeld, an academic author who does not use the term "self-hatred", dismisses such arguments as disingenuous, referring to them as "the ubiquitous rubric 'criticism of Israel,'" stating that "vigorous discussion of Israeli policy and actions is not in question."[4]

- Alan Dershowitz limits the term "self-hatred" to specific Jewish anti-Zionists who "despise anything Jewish, ranging from their religion to the Jewish state", saying it does not apply to all "Israel-bashers."[5]

- The academic historian Jerold Auerbach uses the term Jewish self-loathing to characterize "Jews who perversely seek to bolster their Jewish credentials by defaming Israel."[6]

- The cultural historian Sander Gilman has written, "One of the most recent forms of Jewish self-hatred is the virulent opposition to the existence of the State of Israel."[1] He uses the term not against those who oppose Israel's policy, but against Jews who are opposed to Israel's existence.

- The concept of Jewish self-hatred has been described by Antony Lerman as "an entirely bogus concept",[7] one that "serves no other purpose than to marginalise and demonise political opponents",[8] who says that it is used increasingly as a personal attack in discussions about the "new antisemitism".[8]

- Ben Cohen criticizes Lerman, saying no "actual evidence is introduced to support any of this."[9] Lerman himself recognizes the controversy over whether extreme vilification of Israel amounts to antisemitism, and says that antisemitism can be disguised as anti-Zionism,[7][10] also a concern of Rosenfeld and Gilman as mentioned above.

- The sociologist Irving Louis Horowitz reserves the term for Jews who pose a danger to the Jewish community, using "Jewish self-hater" to describe the so-called "court Jew", "who validates the slander (against Jews) as he attempts to curry the favor of masters and rulers."[11]

- The historian Bernard Wasserstein prefers the term "Jewish anti-Semitism," which he says was often termed "Jewish self-hatred".[12] He asks, "Could a Jew be an anti-Semite?", and responds that many Jews have "internalized elements of anti-Semitic discourse, succumbed to what Theodore Hamerow has called psychological surrender."[vague] Wasserstein goes on to say that self-hating Jews, "afflicted by some form of anti-Semitism[,] were not so much haters of themselves as haters of 'other' Jews."

- The historian Bernard Lewis described Jewish self-hatred as a neurotic reaction to the impact of anti-semitism by Jews accepting, expressing, and even exaggerating, the basic assumptions of the antisemite.[13]

History

[edit]In Abrahamic religion

[edit]According to Ronald Hendel, the Israelites, who were progenitors of the Jews, frequently repudiated their Canaanite heritage by describing their ancestral traditions as "foreign" and "dangerous". Philippe Bohstrom believes Abraham, the ancestor of Israel, was an Amorite but this was later obfuscated by Biblical authors, who adopted Mesopotamian prejudices towards Amorites.[14][15]

Gili Kluger argues that the biblical narratives about Amalek reflect self-hatred among Israelites, where they see Amalek as their "unwelcome brother", "rejected son" and a nation that possessed the inherent vices of Israel. Israelites believed that Amalek descended from Esau, who was the twin brother of Jacob/Israel.[16]

In the New Testament, which is central to Christianity, the letters of Apostle Paul are described by some scholars as 'indiscriminate anti-Jewish polemic' that mirrors Graeco-Roman pagan attitudes to the Jews,[17] despite Paul's Jewish background. Others argue that the letters resonate with Old Testament themes. [18]

In German

[edit]The origins of terms such as "Jewish self-hatred" lie in the mid-19th century feuding between German Orthodox Jews of the Breslau seminary and Reform Jews.[8] Each side accused the other of betraying Jewish identity,[2] the Orthodox Jews accusing the Reform Jews of identifying more closely with German Protestantism and German nationalism than with Judaism.[8]

According to Amos Elon, during 19th-century German-Jewish assimilation, conflicting pressures on sensitive and privileged or gifted young Jews produced "a reaction later known as 'Jewish self-hatred.' Its roots were not simply professional or political but emotional."[19] Elon uses the term "Jewish self-hatred" synonymously with Jewish antisemitism when he points out, "One of the most prominent Austrian anti-Semites was Otto Weininger, a brilliant young Jew who published 'Sex and Character', attacking Jews and women." Elon attributes Jewish antisemitism as a cause in the overall growth of antisemitism when he says,"(Weininger's) book inspired the typical Viennese adage that anti-Semitism did not really get serious until it was taken up by Jews."

According to John P. Jackson Jr., the concept developed in the late 19th century in German Jewish discourse as "a response of German Jews to popular anti-Semitism that primarily was directed at Eastern European Jews." For German Jews, the Eastern European Jew became the "bad Jew".[20] According to Sander Gilman, the concept of the "self-hating Jew" developed from a merger of the image of the "mad Jew" and the "self-critical Jew",[2] and was developed to counter suggestions that an alleged Jewish stereotype of mental illness was due to inbreeding. "Within the logic of the concept, those who accuse others of being self-hating Jews may themselves be self-hating Jews."[1] Gilman says "the ubiquitousness of self-hatred cannot be denied. And it has shaped the self-awareness of those treated as different perhaps more than they themselves have been aware."[1]: 1

The specific terms "self-hating Jew" and "Jewish self-hatred" only came into use later, developing from Theodor Herzl's polemical use of the term "anti-Semite of Jewish origin", in the context of his project of political Zionism.[2] The underlying concept gained common currency in this context, "since Zionism was an important part of the vigorous debates that were occurring amongst Jews at the time about anti-Semitism, assimilation and Jewish identity."[3] Herzl appears to have introduced the phrase "anti-Semite of Jewish origin" in his 1896 book, Der Judenstaat (The Jews' State), which launched political Zionism.[2]

He was referring to "philanthropic Zionists", assimilated Jews who might wish to remain in their home countries while at the same time encouraging the Jewish proletariat (particularly the poorer Eastern Jews) to emigrate; yet did not support Herzl's political project for a Jewish state.[2] Ironically, Herzl was soon complaining that his "polemical term"[2] was often being applied to him, for example by Karl Kraus.[2] "Assimilationists and anti-Zionists accused Zionists of being self-haters, for promoting the idea of the strong Jew using rhetoric close to that of the Anti-Semites; Zionists accused their opponents of being self-haters, for promoting the image of the Jew that would perpetuate his inferior position in the modern world."[8]

The Austrian-Jewish journalist Anton Kuh argued in a 1921 book Juden und Deutsche (Jews and Germans) that the concept of "Jewish anti-semitism" was unhelpful, and should be replaced with the term "Jewish self-hatred", but it was not until the 1930 publication of the German-Jewish anti-Nazi philosopher Theodor Lessing's book Der Jüdische Selbsthass (Jewish Self-hatred) that the term gained widespread currency.[2] Lessing's book "supposedly charts Lessing's journey from Jewish self-hater to Zionist."[8] In it he analyses the writings of Jews such as Otto Weininger and Arthur Trebitsch who expressed hatred for their own Judaism. Lessing was assassinated by Nazi agents shortly after Hitler came to power.

In English

[edit]In English the first major discussion of the topic was in the 1940s by Kurt Lewin, who was Lessing's colleague at the University of Berlin in 1930.[2] Lewin emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1933, and though focused on Jews also argued for a similar phenomenon among Polish, Italian and Greek immigrants to the United States.[3] Lewin's was a theoretical account, declaring that the issue "is well known among Jews themselves" and supporting his argument with anecdotes.[3] According to Lewin, a self-hating Jew "will dislike everything specifically Jewish, for he will see in it that which keeps him away from the majority for which he is longing. He will show dislike for those Jews who are outspokenly so, and will frequently indulge in self-hatred."[21] Following Lewin's lead, the concept gained widespread currency. "The 1940s and 1950s were 'the age of self-hatred'. In effect, a bitter war broke out over questions of Jewish identity. It was a kind of 'Jewish Cold War'..."[8] in which questions of Jewish identity were contentiously debated. The use of the concept in debates over Jewish identity – for example over resistance to the integration of African Americans into Jewish neighbourhoods – died down by the end of the 1970s, having been "steadily emptied of most of its earlier psychological, social, and theoretical content and became largely a slogan."[22]

The term was used in a derogatory way during the 1940s by "'militant' Zionists",[22] but the 1963 publication of Hannah Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem opened a new chapter. Her criticism of the trial as a "show trial" provoked heated public debate, including accusations of self-hatred, and over-shadowed her earlier work criticising German Jewish parvenu assimilationism.[22] In the following years, after the 1967 Six-Day War and 1973 Yom Kippur War, "willingness to give moral and financial 'support' to Israel constituted what one historian called 'the existential definition of American Jewishness'."[22] "This meant that the opposite was also true: criticism of Israel came to constitute the existential definition of 'Jewish self-hatred'."[8] This is dismissed by Rosenfeld saying it "masquerades as victimization" and "can hardly be expected to be taken seriously" since criticism of Israel "proceeds across all the media in this country and within Israel itself."[4]

Even Commentary, the Jewish journal which had once been "considered the venue of self-hating Jews with questionable commitments to the Zionist project",[22] came under the editorship of Norman Podhoretz to staunchly support Israel.[22] In his 2006 essay "Progressive Jewish Thought and the New Anti-Semitism", Alvin H. Rosenfeld takes "a hard look at Jewish authors" whose statements go well beyond "legitimate criticism of Israel," and considers rhetoric that calls into question Israel's "right to continued existence" to be antisemitic. The use of the concept of self-hatred in Jewish debates about Israel has grown more frequent and more intense in the US and the UK, with the issue particularly widely debated in 2007, leading to the creation of the British Independent Jewish Voices.[8] The Forward reported that the group was formed by "about 130 generally leftist Jews."[23] It was the Rosenfeld essay, which did not use the term Jewish self-hatred, that led to the 2007 debate. Critics claimed the charge of antisemitism implied Jewish self-hatred to those criticizing Israel. Rosenfeld responded that such claims were "disingenuous" and for some a "dialectical scam validating themselves as intellectual martyrs."[4] The New York Times reported that the essay spotlighted the issue of when "legitimate criticism of Israel ends and antisemitic statements begin."[24]

Social and psychological explanations

[edit]The issue has periodically been covered in the academic social psychology literature on social identity. Such studies "frequently cite Lewin as evidence that people may attempt to distance themselves from membership in devalued groups because they accept, to some degree, the negative evaluations of their group held by the majority and because these social identities are an obstacle to the pursuit of social status."[3] Modern social psychology literature uses terms such as "self-stigmatization", "internalized oppression", and "false consciousness" to describe this type of phenomenon. Author Phyllis Chesler, a professor of psychology and women's studies, in referring to female Jewish self-hatred, points to progressive Jewish women who "seem obsessed with the Palestinian point of view." She believes their rage against oppression, frustration and patriarchy "is being unconsciously transferred onto Israel."[25]

Kenneth Levin, a Harvard psychiatrist, says that Jewish self-hatred has two causes: Stockholm syndrome, where "population segments under chronic siege commonly embrace the indictments of their besiegers however bigoted and outrageous", as well as "the psychodynamics of abused children, who almost invariably blame themselves for their predicament, ascribe it to their being bad, and nurture fantasies that by becoming good they can mollify their abusers and end their torment."[26] According to Howard W. Polsky, the social scientist, "feelings about Jewish marginality are often a step away from self-hatred." He then says, "Jewish self-hatred denotes that a person has adopted gentiles' definition of Jew as bad in one way or another and that being Jewish will hinder their success or identity."[27]

Usage

[edit]It is argued by some academics that the concept of Jewish self-hatred is based on an essentialisation of Jewish identity. Accounts of Jewish self-hatred often suggest that criticizing other Jews, and integrating with Gentile society, reveals hatred of one's own Jewish origins.[3] Yet both in the early twentieth century, where the concept developed, and today, there are groups of Jews who had "important differences in identity based on class, culture, religious outlook, and education", and hostility between these groups can only be considered self-hate "if one assumes that a superordinate Jewish identity should take precedence over other groupings of Jews."[3]

Yet such hostility between groups has at times drawn on some of the rhetoric of antisemitism: "criticism of subgroups of Jews which drew on anti-Semitic rhetoric were common in 19th and 20th century arguments over Jewish identity".[3] In practice, according to one academic, whilst there have been Jewish writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who consistently employed virulent antisemitic rhetoric without seeming to value any aspects of being a Jew, too often "those who accuse others of being self-haters search for examples of when they have criticized Jews or Judaism but ignore examples of when those they criticize have shown they value being a Jew."[3] He argues that Jewish antisemitism does not necessarily amount to self-hatred, implying that "antisemitic Jew" may be a more accurate term to use. Other authors have also shown a preference for using "antisemitism" rather than "self-hatred."[4][12]

The term is in use in Jewish publications such as The Jewish Week (New York) and The Jerusalem Post (Jerusalem) in a number of contexts, often synonymously with antisemitic Jew. It is used "to criticize a performer or artist who portrays Jews negatively; as a shorthand description of supposed psychological conflict in fictional characters; in articles about the erosion of tradition (e.g. marrying out and circumcision); and to discount Jews who criticize Israeli policies or particular Jewish practices."[3] However the widest usage of the term is currently in relation to debates over Israel. "In these debates the accusation is used by right-wing Zionists to assert that Zionism and/or support for Israel is a core element of Jewish identity. Jewish criticism of Israeli policy is therefore considered a turning away from Jewish identity itself."[3]

Thus some of those who have been accused of being a "self-hating Jew" have characterized the term as a replacement for "a charge of anti-Semitism [that] will not stick,"[28] or as "pathologizing" them.[3][29] Some who use the term have equated it with "anti-Semitism",[30][8] on the part of those thus addressed, or with "so called 'enlightened' Jews who refuse to associate themselves with people who practice a 'backward' religion."[31] One novelist, Philip Roth, who — because of the nature of the Jewish characters in his novels, such as the 1969 Portnoy's Complaint[22] — has often been accused of being a "self-hating Jew", argues that all novels deal with human dilemmas and weaknesses (which are present in all communities), and that to self-censor by only writing about positive Jewish characters would represent a submission to antisemitism.[3]

The Israeli-born British Jazz saxophonist, writer and Hebrew speaking anti-Semite of Jewish descent Gilad Atzmon openly used the term to describe himself in a 2010 interview for the Cyprus Mail. In that interview, Atzmon calls himself a "proud self-hating Jew" and also described fellow Jewish anti-Semite, the Austrian Otto Weininger as one as well. At the same time, Atzmon stated that he considers a "self-hating Jew" as very different to a "proud self-hating Jew", considering "proud self-hating Jews" such as himself and Weininger as celebrating the hatred they feel for themselves, the Jewish people, Judaism, Israel and anything else they associate with Jewishness.[32] Atzmon has taken several positions on history and politics associated with anti-Semitism including but not limited to, endorsing on his blog the conspiracy theory that "the Jewish people" are trying to take over the world[33][34][35] (though he later amended the original blog post[36] to replace "the Jewish people" with "Zionists"[37][38]), blaming the entire Jewish people for killing Jesus (including those not even born at the time),[39][40] accusing Gideon Falter (the chairman of the Campaign Against Antisemitism) of faking anti-Semitic incidents for profit (Falter then sued Atzmon for libel which Atzmon lost and was left with expensive legal costs[41]) and promoting the conspiracy theory of Holocaust denial, even publicly advising people to read Holocaust denying books by David Irving.[42] The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC)'s official blog Hatewatch written by David Neiwert noted that Atzmon was "a self-described 'self-hating ex-Jew' whose writings and pronouncements are rich in conspiracy theories, Holocaust trivialization and distortion, and open support of anti-Israeli terrorist groups."[43]

Controversy and criticism of the term

[edit]The legitimacy of the term in modern usage remains controversial. According to the transdenominational Jewish platform My Jewish Learning: "Some scholars have claimed that by labeling another Jew self-hating, the accuser is claiming his or her own Judaism as normative–and implying that the Judaism of the accused is flawed or incorrect, based on a metric of the accuser's own stances, religious beliefs, or political opinions. By arguing with the label, then, the accused is rejecting what has been defined as normative Judaism. The term 'self-hating' thus places the person or object labeled outside the boundaries of the discourse–and outside the boundaries of the community."[44] Haaretz writes that the term is almost exclusively used today by the Jewish right against the Jewish left, and that within left-wing and liberal circles it is "usually considered a joke".[45] Richard Forer, writing for The Huffington Post, rejects the legitimacy of the term as it is commonly used, calling them so divisive that they make tolerance and cooperation impossible, eradicating the possibility for genuine understanding. Forer writes: "The notion that any Jew who is dedicated to justice for all people harbors self-hatred defies common sense. Given the self-esteem it takes to stand for justice amidst fierce denunciation, a more accurate assessment is that these are self-loving Jews."[30]

Jon Stewart, former host of The Daily Show, was repeatedly called a "self-hating Jew" by people whom he described as "fascistic".[46] Considering the term to be like equating someone with the Jews who turned their backs on each other during the Holocaust, he said, "I have people that I lost in the Holocaust and I just … go fuck yourself. How dare you?" Stewart commented that the way his critics used the term—to define who is a Jew and who is not—was formerly always done by people who were not Jewish. He saw this as "more than nationalism". Stewart also criticized right-wing Jews for implying that they are the only ones who can decide what it means to be Jewish. He observed: "And you can't observe Judaism in the way you want to observe. And I never thought that that would be coming from brethren. ... How dare they? That they only know the word of God and are the ones who are able to disseminate it. It's not right."[47] To The Hollywood Reporter, he said, "Look, there's a lot of reasons why I hate myself—being Jewish isn't one of them."[48]

In 2014, Noam Chomsky said that Zionists divided critics of Israeli policy into two groups: antisemitic non-Jews and neurotic self-hating Jews. He observed:

Actually, the locus classicus, the best formulation of this, was by an ambassador to the United Nations, Abba Eban, Israel's ambassador to the United Nations.... He advised the American Jewish community that they had two tasks to perform. One task was to show that criticism of the policy, what he called anti-Zionism—that means actually criticisms of the policy of the state of Israel—were anti-Semitism. That's the first task. Second task, if the criticism was made by Jews, their task was to show that it's neurotic self-hatred, needs psychiatric treatment. Then he gave two examples of the latter category. One was I. F. Stone. The other was me. So, we have to be treated for our psychiatric disorders, and non-Jews have to be condemned for anti-Semitism, if they're critical of the state of Israel. That's understandable why Israeli propaganda would take this position. I don't particularly blame Abba Eban for doing what ambassadors are sometimes supposed to do. But we ought to understand that there is no sensible charge. No sensible charge. There's nothing to respond to. It's not a form of anti-Semitism. It's simply criticism of the criminal actions of a state, period.[49]

Similar terms

[edit]"Self-loathing Jew" is synonymously used with "self-hating Jew." "Antisemitic Jew" can be used synonymously as well. "Self-hating Jew" has also been compared to the term "Uncle Tom" which is used in the African-American community.[50][51] The term "auto-antisemitism" (Hebrew: אוטואנטישמיות, autoantishemiut) is also synonymously used in Hebrew.[52][53][54] In a column in Haaretz, Uzi Zilber used the term "Jew Flu" as a synonym for Jewish self-hatred.[55]

See also

[edit]- Anti-Semite and Jew

- Kapo

- White guilt

- Internalized racism – Adherence to racist beliefs and customs by subordinated groups

- Zionist antisemitism

- Association of German National Jews

- Dan Burros

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gilman, Sander (1986). Jewish Self-Hatred: Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 361. ISBN 9780801840630.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Reitter, Paul (2008). "Zionism and the Rhetoric of Jewish Self-Hatred". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 83 (4): 343–364. doi:10.3200/GERR.83.4.343-364. ISSN 0016-8890.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Finlay, W. Mick L. (2005). "Pathologizing dissent: Identity politics, Zionism and the self‐hating Jew". British Journal of Social Psychology. 44 (2): 201–222. doi:10.1348/014466604X17894. ISSN 0144-6665.

- ^ a b c d Alvin H. Rosenfeld, "Rhetorical Violence and the Jews", The New Republic, February 27, 2007.

- ^ Alan Dershowitz, "The Case for Israel", John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2004, pg. 220.

- ^ Auerbach, Jerold (2015-08-17). "Jews Against Themselves, by Edward Alexander (REVIEW)". The Algemeiner. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ a b Lerman, Antony (12 September 2008). "Jews attacking Jews". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Antony Lerman, Jewish Quarterly, "Jewish Self-Hatred: Myth or Reality?", Summer 2008

- ^ "Anthony Lerman Plays Politics with Antisemitism", The Propagandist, September 12, 2008.

- ^ "Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: Ben Cohen Debates Antony Lerman", The Propagandist, June 18, 2008.

- ^ Horowitz, Irving Louis (2005). "New trends and old hatreds". Society. 43 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1007/BF02687353. ISSN 0147-2011.

- ^ a b Bernard Wasserstein, "On the Eve," Simon and Schuster 2012, p. 211.

- ^ Bernard Lewis, "Semites and Anti-Semites," W. W. Norton & Company 1999, pp. 255-256.

- ^ Hendel, Ronald (2005). Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–30. doi:10.1093/0195177967.001.0001. ISBN 9780199784622.

- ^ Bohstrom, Philippe (February 6, 2017). "Peoples of the Bible: The Legend of the Amorites". Haaretz. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024.

- ^ Kugler, Gili (2020). "Metaphysical Hatred and Sacred Genocide: The Questionable Role of Amalek in Biblical Literature". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1827781. S2CID 228959516 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Luckensmeyer, David (2009-01-21). The Eschatology of First Thessalonians (1 ed.). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 167-171. doi:10.13109/9783666539695. ISBN 978-3-525-53969-9.

- ^ Downey, Amy Karen (2011-01-01). Paul's Conundrum: Reconciling 1 Thessalonians 2:13-16 and Romans 9:1-5 in Light of His Calling and His Heritage. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60899-457-1.

- ^ Amos Elon,"The Pity of It All : a History of Jews in Germany, 1743-1933," Metropolitan Books 2002, pp. 231-237.

- ^ Jackson, John P Jr; Jackson, John P (2001). Social Scientists for Social Justice: Making the Case Against Segregation. NYU Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-8147-4266-2. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

Social Scientists for Social Justice.

- ^ Lewin, Kurt (1997). Resolving social conflicts and field theory in social science. Washington: American Psychological Association. p. 164. doi:10.1037/10269-000. ISBN 978-1-55798-415-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Glenn, Susan Anita (2006). "The Vogue of Jewish Self-Hatred in Post-World War II America". Jewish Social Studies. 12 (3): 95–136. doi:10.1353/jss.2006.0025. ISSN 1527-2028.

- ^ Spence, Rebecca (2007-02-10). "Left-wing Critics of Israel Launch Blog To Combat Alleged Intimidation". The Forward. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (2007-01-31). "Essay linking liberal Jews and anti-Semitism sparks furor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-11-30. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Phyllis Chesler, "The New Anti-Semitism," Josse-Bass Wiley Imprint 2005, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Kenneth Levin "The Psychology of Populations under Chronic Siege", Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism, No. 46 2 July 2006, Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Accessed Feb 2010

- ^ Howard W. Polsky, "How I am a Jew, Adventures into my Jewish-American Identity," University Press of America 2002, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Gibson, Martin (2009-01-23). "No choice but to speak out – Israeli musician 'a proud self-hating Jew'". The Gisborne Herald. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ Marqusee, Mike (2008-03-04). "The first time I was called a self-hating Jew". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ a b Forer, Richard (2012-08-10). "The Self-Hating Jew: A Strategy To Hide From Self-Reflection". HuffPost. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Brackman, Rabbi Levi (September 1, 2006). "Confronting the self hating Jew". Israel Jewish Scene. ynetnews. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ Theo Panayides, 'Wandering jazz player,', Cyprus Mail, 21 February 2010: "My ethical duty is to say the things that I know and feel. I'm an artist. Do you know.. this is something I learned from Otto Weininger, the Austrian philosopher. He was a clever boy, killed himself when he was 21. ..He was definitely a proud self-hating Jew! I'm not a self-hating Jew: I'm a proud self-hating Jew! It's a big difference… I celebrate my hatred towards everything I represent – or better to say [everything] I'm associated with".

- ^ Chait, Jonathan (26 September 2011). "John Mearsheimer Ready for Rosh Hashanah in Style". New York Magazine.

- ^ Fineberg, Michael; Samuels, Shimon; Weitzman, Mark (2007). Antisemitism: The Generic Hatred: Essays in Memory of Simon Wiesenthal. Vallentine Mitchell. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-85303-745-3.

- ^ Jazz Times, Volume 35, Issues 6-10. Jazz Times. 2005. p. 22.

- ^ Landy, David (2011). Jewish Identity and Palestinian Rights: Diaspora Jewish Opposition to Israel. Zed Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-84813-929-9.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (9 June 2022). "Labour MP apologises for backing 'antisemitic' jazz musician". The Guardian.

- ^ Frot, Mathilde (2019-11-04). "Venue denies antisemitism after hosting Interfaith for Palestine event". Jewish News. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Hirsh, David (2006-11-30). "Openly embracing prejudice". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Hirsh, David (2006-04-03). "What charge?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Sugarman, Daniel (28 November 2018). "Gilad Atzmon forced to ask supporters for funds after Campaign Against Antisemitism libel lawsuit". Jewish Chronicle.

- ^ "Jewish students told 'don't study at LSE' by Board president". Jewish News Online. 23 March 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ David Neiwert (January 27, 2015). "Onetime Antiwar, Environmental Protester Veers Into the Seamy World of Anti-Semitism". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Gerson, Jordie. "Self-Hating Jews". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Ilany, Ofri (2 July 2015). "Self-hating Jews are not necessarily leftists". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ "Jon Stewart lashes out at critics who call him a self-hating Jew". Ynetnews. 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Dekel, Jon. "Jon Stewart on criticism of his coverage of Israel". canada.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Guthrie, Marisa (2014-08-28). "Jon Stewart on Directorial Debut 'Rosewater,' His 'Daily Show' Future and Those Israel-Gaza Comments". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (27 November 2014). "Noam Chomsky at United Nations: It Would Be Nice if the United States Lived Up to International Law". Democracy Now! (Interview). Interviewed by Amy Goodman. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Eugene Kane, "A phrase whose time has come and gone Archived 2007-04-11 at the Wayback Machine", Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 10, 2002.

- ^ Alan Snitow and Deborah Kaufman, BLACKS & JEWS: Facilitator Guide, 1998.

- ^ Hendelsaltz, Michael. "Letting the animals live". Haaretz (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ Dahan, Alon (2006-12-07). "The history of self-hatred". nfc (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ Dahan, Alon (2006-12-13). "Holocaust denial in Israel". nfc (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ Zilber, Uzi (25 December 2009). "The Jew Flu: The strange illness of Jewish anti-Semitism". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Henry Bean, The Believer: Confronting Jewish Self-Hatred, Thunder's Mouth Press, 2002. ISBN 1-56025-372-X.

- David Biale, "The Stars & Stripes of David", The Nation, May 4, 1998.

- John Murray Cuddihy, Ordeal of Civility: Freud, Marx, Levi-Strauss, and the Jewish Struggle With Modernity, Beacon Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8070-3609-9.

- Sander L. Gilman, Jewish Self-Hatred: Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8018-4063-5.

- Theodor Lessing, "Jewish Self-Hatred", Nativ (Hebrew: translated from German), 17 (96), 1930/2004, pp. 49–54 (Der Jüdische Selbsthass, 1930).

- Kurt Lewin, "Self-Hatred Among Jews", Contemporary Jewish Record, June 1941. Reprinted in Kurt Lewin, Resolving Social Conflicts: Selected Papers on Group Dynamics, Harper & Row, 1948.

- David Mamet, The Wicked Son: Anti-Semitism, Self-hatred, and the Jews, Schocken Books, 2006. ISBN 0-8052-4207-4.

- Raphael Patai, The Jewish Mind, Wayne State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8143-2651-X. Chapter 17, "Jewish Self-Hate".

External links

[edit]- "Ask the Rabbis: What is a 'Self-Hating Jew'?", Moment, November/December 2009.

- Rabbi Michael Lerner, "Israel's Jewish Critics Aren't 'Self-Hating'", Los Angeles Times, April 28, 2002. Reprinted at Common Dreams NewsCenter.

- Daniel Levitas, "Hate and Hypocrisy: What is behind the rare-but-recurring phenomenon of Jewish anti-Semites?", Southern Poverty Law Center Intelligence Report, Winter 2002.

- Jacqueline Rose, "The myth of self-hatred, The Guardian, February 8, 2007.

- Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, "Love, Hate, and Jewish Identity", First Things, November 1997.

- Menachem Wecker, "In Defense of 'Self-Hating' Jews: Conversations with the Targets of Masada2000's S.H.I.T. List", Jewish Currents, May 2007.

- (in French) Martine Gilson, Le petit soldat de la pieuvre noire, Nouvel observateur, 2003-10-09

- (in French) Les « traîtres juifs » d'Alexandre Adler, 2003-11-01