Jealousy

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Jealousy generally refers to the thoughts or feelings of insecurity, fear, and concern over a relative lack of possessions or safety.

Jealousy can consist of one or more emotions such as anger, resentment, inadequacy, helplessness or disgust. In its original meaning, jealousy is distinct from envy, though the two terms have popularly become synonymous in the English language, with jealousy now also taking on the definition originally used for envy alone. These two emotions are often confused with each other, since they tend to appear in the same situation.[1]

Jealousy is a typical experience in human relationships, and it has been observed in infants as young as five months.[2][3][4][5] Some researchers claim that jealousy is seen in all cultures and is a universal trait.[6][7][8] However, others claim jealousy is a culture-specific emotion.[9]

Jealousy can either be suspicious or reactive,[10] and it is often reinforced as a series of particularly strong emotions and constructed as a universal human experience. Psychologists have proposed several models to study the processes underlying jealousy and have identified factors that result in jealousy.[11] Sociologists have demonstrated that cultural beliefs and values play an important role in determining what triggers jealousy and what constitutes socially acceptable expressions of jealousy.[12] Biologists have identified factors that may unconsciously influence the expression of jealousy.[13]

Throughout history, artists have also explored the theme of jealousy in paintings, films, songs, plays, poems, and books, and theologians have offered religious views of jealousy based on the scriptures of their respective faiths.

Etymology

[edit]The word stems from the French jalousie, formed from jaloux (jealous), and further from Low Latin zelosus (full of zeal), in turn from the Greek word ζῆλος (zēlos), sometimes "jealousy", but more often in a positive sense "emulation, ardour, zeal"[14][15] (with a root connoting "to boil, ferment"; or "yeast").[citation needed] The "biblical language" zeal would be known as "tolerating no unfaithfulness" while in middle English zealous is good.[16] One origin word gelus meant "Possessive and suspicious" the word then turned into jelus.[16]

Since William Shakespeare's use of terms like "green-eyed monster",[17] the color green has been associated with jealousy and envy, from which the expression "green with envy", is derived.

Theories

[edit]Scientific examples

[edit]

People do not express jealousy through a single emotion or a single behavior.[18][19][20] They instead express jealousy through diverse emotions and behaviors, which makes it difficult to form a scientific definition of jealousy. Scientists instead define it in their own words, as illustrated by the following examples:

- "Romantic jealousy is here defined as a complex of thoughts, feelings, and actions which follow threats to self-esteem and/or threats to the existence or quality of the relationship, when those threats are generated by the perception of potential attraction between one's partner and a (perhaps imaginary) rival."[21]

- "Jealousy, then, is any aversive reaction that occurs as the result of a partner's extradyadic relationship that is considered likely to occur."[22]

- "Jealousy is conceptualized as a cognitive, emotional, and behavioral response to a relationship threat. In the case of sexual jealousy, this threat emanates from knowing or suspecting that one's partner has had (or desires to have) sexual activity with a third party. In the case of emotional jealousy, an individual feels threatened by her or his partner's emotional involvement with and/or love for a third party."[23]

- "Jealousy is defined as a defensive reaction to a perceived threat to a valued relationship, arising from a situation in which the partner's involvement with an activity and/or another person is contrary to the jealous person's definition of their relationship."[24]

- "Jealousy is triggered by the threat of separation from, or loss of, a romantic partner, when that threat is attributed to the possibility of the partner's romantic interest in another person."[25]

These definitions of jealousy share two basic themes. First, all the definitions imply a triad composed of a jealous individual, a partner, and a perception of a third party or rival. Second, all the definitions describe jealousy as a reaction to a perceived threat to the relationship between two people, or a dyad. Jealous reactions typically involve aversive emotions and/or behaviors that are assumed to be protective for their attachment relationships. These themes form the essential meaning of jealousy in most scientific studies.

Comparison with envy

[edit]Popular culture uses the word jealousy as a synonym for envy. Many dictionary definitions include a reference to envy or envious feelings. In fact, the overlapping use of jealousy and envy has a long history.

The terms are used indiscriminately in such popular 'feel-good' books as Nancy Friday's Jealousy, where the expression 'jealousy' applies to a broad range of passions, from envy to lust and greed. While this kind of usage blurs the boundaries between categories that are intellectually valuable and psychologically justifiable, such confusion is understandable in that historical explorations of the term indicate that these boundaries have long posed problems. Margot Grzywacz's fascinating etymological survey of the word in Romance and Germanic languages[26] asserts, indeed, that the concept was one of those that proved to be the most difficult to express in language and was therefore among the last to find an unambiguous term. Classical Latin used invidia, without strictly differentiating between envy and jealousy. It was not until the postclassical era that Latin borrowed the late and poetic Greek word zelotypia and the associated adjective zelosus. It is from this adjective that are derived French jaloux, Provençal gelos, Italian geloso, Spanish celoso, and Portuguese cioso.[27]

Perhaps the overlapping use of jealousy and envy occurs because people can experience both at the same time. A person may envy the characteristics or possessions of someone who also happens to be a romantic rival.[28] In fact, one may even interpret romantic jealousy as a form of envy.[29] A jealous person may envy the affection that their partner gives to a rival – affection the jealous person feels entitled to themselves. People often use the word jealousy as a broad label that applies to both experiences of jealousy and experiences of envy.[30]

Although popular culture often uses jealousy and envy as synonyms, modern philosophers and psychologists have argued for conceptual distinctions between jealousy and envy. For example, philosopher John Rawls[31] distinguishes between jealousy and envy on the ground that jealousy involves the wish to keep what one has, and envy the wish to get what one does not have. Thus, a child is jealous of her parents' attention to a sibling, but envious of her friend's new bicycle. Psychologists Laura Guerrero and Peter Andersen have proposed the same distinction.[32] They claim the jealous person "perceives that he or she possesses a valued relationship, but is in danger of losing it or at least of having it altered in an undesirable manner," whereas the envious person "does not possess a valued commodity, but wishes to possess it." Gerrod Parrott draws attention to the distinct thoughts and feelings that occur in jealousy and envy.[33][34]

The common experience of jealousy for many people may involve:

- Fear of loss

- Suspicion of or anger about a perceived betrayal

- Low self-esteem and sadness over perceived loss

- Uncertainty and loneliness

- Fear of losing an important person to another

- Distrust

The experience of envy involves:

- Feelings of inferiority

- Longing

- Resentment of circumstances

- Ill will towards envied person often accompanied by guilt about these feelings

- Motivation to improve

- Desire to possess the attractive rival's qualities

- Disapproval of feelings

- Sadness towards other's accomplishments

Parrott acknowledges that people can experience envy and jealousy at the same time. Feelings of envy about a rival can even intensify the experience of jealousy.[35] Still, the differences between envy and jealousy in terms of thoughts and feelings justify their distinction in philosophy and science.

In psychology

[edit]Jealousy involves an entire "emotional episode" including a complex narrative. This includes the circumstances that lead up to jealousy, jealousy itself as emotion, any attempt at self regulation, subsequent actions and events, and ultimately the resolution of the episode. The narrative can originate from experienced facts, thoughts, perceptions, memories, but also imagination, guesses and assumptions. The more society and culture matter in the formation of these factors, the more jealousy can have a social and cultural origin. By contrast, jealousy can be a "cognitively impenetrable state", where education and rational belief matter very little.[36]

One possible explanation of the origin of jealousy in evolutionary psychology is that the emotion evolved in order to maximize the success of our genes: it is a biologically based emotion selected to foster the certainty about the paternity of one's own offspring. A jealous behavior, in women, is directed into avoiding sexual betrayal and a consequent waste of resources and effort in taking care of someone else's offspring.[37] There are, additionally, cultural or social explanations of the origin of jealousy. According to one, the narrative from which jealousy arises can be in great part made by the imagination. Imagination is strongly affected by a person's cultural milieu. The pattern of reasoning, the way one perceives situations, depends strongly on cultural context. It has elsewhere been suggested that jealousy is in fact a secondary emotion in reaction to one's needs not being met, be those needs for attachment, attention, reassurance or any other form of care that would be otherwise expected to arise from that primary romantic relationship.

While mainstream psychology considers sexual arousal through jealousy a paraphilia, some authors on sexuality have argued that jealousy in manageable dimensions can have a definite positive effect on sexual function and sexual satisfaction. Studies have also shown that jealousy sometimes heightens passion towards partners and increases the intensity of passionate sex.[38][39]

Jealousy in children and teenagers has been observed more often in those with low self-esteem and can evoke aggressive reactions. One such study suggested that developing intimate friends can be followed by emotional insecurity and loneliness in some children when those intimate friends interact with others. Jealousy is linked to aggression and low self-esteem.[40] Research by Sybil Hart, PhD, at Texas Tech University indicates that children are capable of feeling and displaying jealousy at as young as six months.[41] Infants showed signs of distress when their mothers focused their attention on a lifelike doll. This research could explain why children and infants show distress when a sibling is born, creating the foundation for sibling rivalry.[42]

In addition to traditional jealousy comes Obsessive Jealousy, which can be a form of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.[43] This jealousy is characterized by obsessional jealousy and thoughts of the partner.

In sociology

[edit]Anthropologists have claimed that jealousy varies across cultures. Cultural learning can influence the situations that trigger jealousy and the manner in which jealousy is expressed. Attitudes toward jealousy can also change within a culture over time. For example, attitudes toward jealousy changed substantially during the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. People in the United States adopted much more negative views about jealousy. As men and women became more equal it became less appropriate or acceptable to express jealousy.

Romantic jealousy

[edit]

Romantic jealousy arises as a result of romantic interest.

It is defined as “a complex of thoughts, feelings, and actions that follow threats to self-esteem and/or threats to the existence or quality of the relationship when those threats are generated by the perception of a real or potential romantic attraction between one's partner and a (perhaps imaginary) rival.”[44] Different from sexual jealousy, romantic jealousy is triggered by threats to self and relationship (rather than sexual interest in another person). Factors, such as feelings of inadequacy as a partner, sexual exclusivity, and having put relatively more effort into the relationship, are positively correlated to relationship jealousy in both genders.

Communicative responses

[edit]As romantic jealousy is a complicated reaction that has multiple components, i.e., thoughts, feelings, and actions, one aspect of romantic jealousy that is under study is communicative responses. Communicative responses serve three critical functions in a romantic relationship, i.e., reducing uncertainty, maintaining or repairing relationship, and restoring self-esteem.[45] If done properly, communicative responses can lead to more satisfying relationships after experiencing romantic jealousy.[46][47]

There are two subsets of communicative responses: interactive responses and general behavior responses. Interactive responses is face-to-face and partner-directed while general behavior responses may not occur interactively.[45] Guerrero and colleagues further categorize multiple types of communicative responses of romantic jealousy. Interactive responses can be broken down to six types falling in different places on continua of threat and directness:

- Avoidance/Denial (low threat and low directness). Example: becoming silent; pretending nothing is wrong.

- Integrative Communication (low threat and high directness). Example: explaining feelings; calmly questioning partner.

- Active Distancing (medium threat and medium directness). Example: decreasing affection.

- Negative Affect Expression (medium threat and medium directness). Example: venting frustration; crying or sulking.

- Distributive Communication (high threat and high directness). Example: acting rude; making hurtful or abrasive comments.

- Violent Communication/Threats (high threat and high directness). Example: using physical force.

Guerrero and colleagues have also proposed five general behavior responses. The five sub-types differ in whether a response is 1) directed at partner or rival(s), 2) directed at discovery or repair, and 3) positively or negatively valenced:

- Surveillance/ Restriction (rival-targeted, discovery-oriented, commonly negatively valenced). Example: observing rival; trying to restrict contact with partner.

- Rival Contacts (rival-targeted, discovery-oriented/repair-oriented, commonly negatively valenced). Example: confronting rival.

- Manipulation Attempts (partner-targeted, repair-oriented, negatively valenced). Example: tricking partner to test loyalty; trying to make partner feel guilty.

- Compensatory Restoration (partner-targeted, repair-oriented, commonly positively valenced). Example: sending flowers to partner.

- Violent Behavior (-, -, negatively valenced). Example: slamming doors.

While some of these communicative responses are destructive and aggressive, e.g., distributive communication and active distancing, some individuals respond to jealousy in a more constructive way.[48] Integrative communication, compensatory restoration, and negative affect expression have been shown to lead to positive relation outcomes.[49] One factor that affects the type of communicative responses elicited in an individual is emotions. Jealousy anger is associated with more aggressive communicative response while irritation tends to lead to more constructive communicative behaviors.

Researchers also believe that when jealousy is experienced it can be caused by differences in understanding the commitment level of the couple, rather than directly being caused by biology alone. The research identified that if a person valued long-term relationships more than being sexually exclusive, those individuals were more likely to demonstrate jealousy over emotional rather than physical infidelity.[50]

Through a study conducted in three Spanish-Speaking countries, it was determined that Facebook jealousy also exists. This Facebook jealousy ultimately leads to increased relationship jealousy and study participants also displayed decreased self esteem as a result of the Facebook jealousy.[51]

Sexual jealousy

[edit]

Sexual jealousy may be triggered when a person's partner displays sexual interest in another person.[52] The feeling of jealousy may be just as powerful if one partner suspects the other is guilty of infidelity. Fearing that their partner will experience sexual jealousy the person who has been unfaithful may lie about their actions in order to protect their partner. Experts often believe that sexual jealousy is in fact a biological imperative. It may be part of a mechanism by which humans and other animals ensure access to the best reproductive partners.

It seems that male jealousy in heterosexual relationships may be influenced by their female partner's phase in her menstrual cycle. In the period around and shortly before ovulation, males are found to display more mate-retention tactics, which are linked to jealousy.[53] Furthermore, a male is more likely to employ mate-retention tactics if their partner shows more interest in other males, which is more likely to occur in the pre-ovulation phase.[54]

Contemporary views on gender-based differences

[edit]According to Rebecca L. Ammon in The Osprey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons (2004), the Parental Investment Model based on parental investment theory posits that more men than women ratify sex differences in jealousy. In addition, more women over men consider emotional infidelity (fear of abandonment) as more distressing than sexual infidelity.[55] According to the attachment theory, sex and attachment style makes significant and unique interactive contributions to the distress experienced. Security within the relationship also heavily contributes to one's level of distress. These findings imply that psychological and cultural mechanisms regarding sex differences may play a larger role than expected. The attachment theory also claims to reveal how infants' attachment patterns are the basis for self-report measures of adult attachment. Although there are no sex differences in childhood attachment, individuals with dismissing behavior were more concerned with the sexual aspect of relationships. As a coping mechanism these individuals would report sexual infidelity as more harmful. Moreover, research shows that audit attachment styles strongly conclude with the type of infidelity that occurred. Thus psychological and cultural mechanisms are implied as unvarying differences in jealousy that play a role in sexual attachment.[56]

In 1906, The American Journal of Psychology had reported that "the weight of quotable (male) authority is to the effect that women are more susceptible to jealousy". This claim was accompanied in the journal by a quote from Confucius: "The five worst maladies that afflict the female mind are indocility, discontent, slander, jealousy and silliness."[57]

Emotional jealousy was predicted to be nine times more responsive in females than in males. The emotional jealousy predicted in females also held turn to state that females experiencing emotional jealousy are more violent than men experiencing emotional jealousy.[58]

There are distinct emotional responses to gender differences in romantic relationships. For example, due to paternity uncertainty in males, jealousy increases in males over sexual infidelity rather than emotional. According to research more women are likely to be upset by signs of resource withdraw (i.e. another female) than by sexual infidelity. A large amount of data supports this notion. However, one must consider for jealousy the life stage or experience one encounters in reference to the diverse responses to infidelity available. Research states that a componential view of jealousy consist of specific set of emotions that serve the reproductive role.[citation needed] However, research shows that both men and women would be equally angry and point the blame for sexual infidelity, but women would be more hurt by emotional infidelity. Despite this fact, anger surfaces when both parties involved are responsible for some type of uncontrollable behavior, sexual conduct is not exempt. Some behavior and actions are controllable such as sexual behavior. However hurt feelings are activated by relationship deviation. No evidence is known to be sexually dimorphic in both college and adult convenience samples.[clarification needed] The Jealousy Specific Innate Model (JSIM) proved to not be innate, but may be sensitive to situational factors. As a result, it may only activate at stages. For example, it was predicted that male jealousy decreases as females reproductive values decreases.[59]

A second possibility that the JSIM effect is not innate but is cultural. Differences have been highlighted in socio-economic status specific such as the divide between high school and collegiate individuals. Moreover, individuals of both genders were angrier and blamed their partners more for sexual infidelities but were more hurt by emotional infidelity. Jealousy is composed of lower-level emotional states (e.g., anger and hurt) which may be triggered by a variety of events, not by differences in individuals' life stage. Although research has recognized the importance of early childhood experiences for the development of competence in intimate relationships, early family environment is recently being examined as we age). Research on self-esteem and attachment theory suggest that individuals internalize early experiences within the family which subconsciously translates into their personal view of worth of themselves and the value of being close to other individuals, especially in an interpersonal relationship.[60]

In animals

[edit]A study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, replicated jealousy studies done on humans on canines. They reported, in a paper published in PLOS ONE in 2014, that a significant number of dogs exhibited jealous behaviors when their human companions paid attention to dog-like toys, compared to when their human companions paid attention to non-social objects.[61]

In addition, Jealousy has been speculated to be a potential factor in incidences of aggression or emotional tension in dogs.[62][63] Mellissa Starling, an animal behavior consultant of the University of Sydney, noted that "dogs are social animals and they obey a group hierarchy. Changes in the home, like the arrival of a baby, can prompt a family pet to behave differently to what one might expect."[64]

Applications

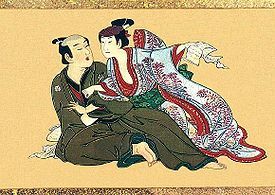

[edit]In fiction, film, and art

[edit]

Artistic depictions of jealousy occur in fiction, films, and other art forms such as painting and sculpture. Jealousy is a common theme in literature, art, theatre, and film. Often, it is presented as a demonstration of particularly deep feelings of love, rather than a destructive obsession.

A study done by Ferris, Smith, Greenberg, and Smith[65] looked into the way people saw dating and romantic relationships based on how many reality dating shows they watched.[66] People who spent a large amount of time watching these reality dating shows "endorsed" or supported the "dating attitudes" that would be shown on the show.[66] While the other people who do not spend time watching reality dating shows did not mirror the same ideas.[66] This means if someone watches a reality dating show that displays men and women reacting violently or aggressively towards their partner due to jealousy they can mirror that.[66] This is reflected in romantic movies as well.[66] Jessica R. Frampton conducted a study looking into romantic jealousy in movies. The study found that there were "230 instances of romantic jealousy were identified in the 51 top-grossing romantic comedies from 2002–2014"[66] Some of the films did not display romantic jealousy however, some featured many examples of romantic jealousy.[66] This was due to the fact that some of the top-grossing movies did not contain a rival or romantic competition.[66] While others such as Forgetting Sarah Marshall was said to contain "19 instances of romantic jealousy."[66] Out of the 230 instances 58% were reactive jealousy while 31% showed possessive jealousy.[66] The last 11% displayed anxious jealousy it was seen the least in all 230 cases.[66] Out of the 361 reactions to the jealousy found 53% were found to be "Destructive responses."[66] Only 19% of responses were constructive while 10% showed avoidant responses.[66] The last 18% were considered "rival focused responses" which lead to the finding that "there was a higher than expected number of rival-focused responses to possessive jealousy."[66]

In religion

[edit]Jealousy in religion examines how the scriptures and teachings of various religions deal with the topic of jealousy. Religions may be compared and contrasted on how they deal with two issues: concepts of divine jealousy, and rules about the provocation and expression of human jealousy.

Cross culture

[edit]A study was done in order to cross examine jealousy among four different cultures, Ireland, Thailand, India and the United States.[67] These cultures were chosen to demonstrate differences in expression across cultures. The study posits that male-dominant cultures are more likely to express and reveal jealousy.[67] The survey found that Thais are less likely to express jealousy than the other three cultures.[67] This is because the men in these cultures are rewarded in a way for showing jealousy due to the fact that some women interpret it as love.[67] This can also be seen when watching romantic comedies when males show they are jealous of a rival or emotionally jealous women perceive it as men caring more.[67]

See also

[edit]- Compersion — empathizing with the joy of another.

- Crime of passion

- Delusional disorder, jealous subtype

- Inferiority complex

- Pathological jealousy

- Emotion

- Relational transgression

References

[edit]- Pistole, Johthan; Roberts, Carole; Mosko, Amber (2010). "Commitment predictors: Long-distance versus geographically close relationships". Journal of Counseling & Development. 88 (2): 2. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x.

- Rydell, Robert J.; McConnell, Allen R.; Bringle, Robert G. (2004). "Jealousy and commitment: Perceived threat and the effect of relationship alternatives". Personal Relationships. 11 (4): 451–468. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00092.x.

- Lyhda, Belcher (2009). " Different Types of Jealousy" livestrong.com

- Green, Melanie; Sabin, John (2006). "Gender, Socioeconomic Status, age and jealousy: Emotional responses to infidelity in a national sample". Emotion. 6 (2): 330–4. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "What Is the Difference Between Envy and Jealousy? | Psychology Today". www.psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Draghi-Lorenz, R. (2000). Five-month-old infants can be jealous: Against cognitivist solipsism. Paper presented in a symposium convened for the XIIth Biennial International Conference on Infant Studies (ICIS), 16–19 July, Brighton, UK.

- ^ Hart, S (2002). "Jealousy in 6-month-old infants". Infancy. 3 (3): 395–402. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0303_6. PMID 33451216.

- ^ Hart, S (2004). "When infants lose exclusive maternal attention: Is it jealousy?". Infancy. 6: 57–78. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0601_3.

- ^ Shackelford, T.K.; Voracek, M.; Schmitt, D.P.; Buss, D.M.; Weekes-Shackelford, V.A.; Michalski, R.L. (2004). "Romantic jealousy in early adulthood and in later life". Human Nature. 15 (3): 283–300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.387.4722. doi:10.1007/s12110-004-1010-z. PMID 26190551. S2CID 10348416.

- ^ Buss, D.M. (2000). The Dangerous Passion: Why Jealousy is as Necessary as Love and Sex. New York: Free Press.

- ^ Buss DM (December 2001), "Human nature and culture: an evolutionary psychological perspective", J Pers, 69 (6): 955–78, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.152.1985, doi:10.1111/1467-6494.696171, PMID 11767825.

- ^ White, G.L., & Mullen, P.E. (1989). Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- ^ Peter Salovey (1991). The Psychology of Jealousy and Envy. Guilford Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-89862-555-4.

- ^ Rydell RJ, Bringle RG Differentiating reactive and suspicious jealousy Social Behavior and Personality An International Journal 35(8):1099-1114 Jan 2007

- ^ Chung, Mingi; Harris, Christine R. (2018). "Jealousy as a Specific Emotion: The Dynamic Functional Model". Emotion Review. 10 (4): 272–287. doi:10.1177/1754073918795257. S2CID 149821370.

- ^ Clanton, Gordon (1996). "A Sociology of Jealousy". International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 16 (9/10): 171–189. doi:10.1108/eb013274.

- ^ "Scientists pinpoint jealousy in the monogamous brain". Science & research news | Frontiers. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jealous, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Zelos, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus

- ^ a b "jealous | Origin and meaning of jealous by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Othello, Act III, Scene 3, 170

- ^ Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.

- ^ Clanton, G. & Smith, L. (1977) Jealousy. New Jersey: Prentice- Hall, Inc.

- ^ Bram Buunk, B. (1984). Jealousy as related to attributions for the partner's behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 47, 107–112.

- ^ White, G.L. (1981). "Jealousy and partner's perceived motives for attraction to a rival". Social Psychology Quarterly. 44 (1): 24–30. doi:10.2307/3033859. JSTOR 3033859.

- ^ Bringle, R.G. & Buunk, B.P. (1991). Extradyadic relationships and sexual jealousy. In K. McKinney and S. Sprecher (Eds.), Sexuality in Close Relationships (pp. 135–153) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Guerrero, L.K., Spitzberg, B.H., & Yoshimura, S.M. (2004). Sexual and Emotional Jealousy. In J.H. Harvey, S. Sprecher, and A. Wenzel (Eds.), The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships (pp. 311–345). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Bevan, J.L. (2004). "General partner and relational uncertainty as consequences of another person's jealousy expression". Western Journal of Communication. 68 (2): 195–218. doi:10.1080/10570310409374796. S2CID 152205568.

- ^ Sharpsteen, D.J.; Kirkpatrick, L.A. (1997). "Romantic jealousy and adult romantic attachment". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 72 (3): 627–640. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.627. PMID 9120787.

- ^ Margot Grzywacz, "Eifersucht" in den romanischen Sprachen (Bochum-Langendreer, Germany: H. Pöppinghaus, 1937), p. 4

- ^ Lloyd, R. (1995). Closer & Closer Apart: Jealousy in Literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- ^ Parrot, W.G.; Smith, R.H. (1993). "Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 64 (6): 906–920. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.906. PMID 8326472. S2CID 24219423.

- ^ Kristjansson, K. (2002). Justifying Emotions: Pride and Jealousy.

- ^ Smith, R.H.; Kim, S.H.; Parrott, W.G. (1988). "Envy and jealousy: Semantic problems and experiential distinctions". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 14 (2): 401–409. doi:10.1177/0146167288142017. PMID 30045477. S2CID 51720365.

- ^ Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ^ Guerrero, L.K., & Andersen, P.A. (1998). The dark side of jealousy and envy: desire, delusion, desperation, and destructive communication. In W.R. Cupach and B.H. Spitzberg (Eds.), The Dark Side of Close Relationships, (pp. ). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Parrott, W.G. (1992). The emotional experiences of envy and jealousy. In P. Salovey (Ed.), The Psychology of Jealousy and Envy (pp. 3–29). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- ^ Staff, P.T. (January–February 1994), "A devastating difference", Psychology Today, Document ID 1544, archived from the original on 27 April 2006, retrieved 8 July 2006

- ^ Pines, A.; Aronson, E. (1983). "Antecedents, correlates, and consequences of sexual jealousy". Journal of Personality. 51: 108–136. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1983.tb00857.x.

- ^ Haslam, Nick; Bornstein, Brian H. (September 1996). "Envy and jealousy as discrete emotions: A taxometric analysis". Motivation and Emotion. 20 (3): 255–272. doi:10.1007/bf02251889. ISSN 0146-7239. S2CID 40599921.

- ^ Ramachandran, Vilayanur S.; Jalal, Baland (2017). "The Evolutionary Psychology of Envy and Jealousy". Frontiers in Psychology. 8: 1619. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01619. PMC 5609545. PMID 28970815.

- ^ Emotions and sexuality. In K. McKinney and S. Sprecher (Eds.), Sexuality, in close relationships (pp. 49–70). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Pines, A. (1992). Romantic jealousy: Understanding and conquering the shadow of love. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ "Study links jealousy with aggression, low self-esteem". Apa.org. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Hart, S.; Carrington, H. (2002). "Jealousy in six-month-old infants". Infancy. 3 (3): 395–402. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0303_6. PMID 33451216.

- ^ Hart, S.; Carrington, H.; Tronick, E. Z.; Carroll, S. (2004). "When infants lose exclusive maternal attention: Is it jealousy?". Infancy. 6: 57–78. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0601_3.

- ^ Curling, Louise; Kellett, Stephen; Totterdell, Peter (December 2018). "Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Obsessive Morbid Jealousy: A Case Series | Scinapse | Academic search engine for paper". Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. doi:10.1037/INT0000122. S2CID 149698347. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ White, Gregory L. (1 December 1981). "A model of romantic jealousy". Motivation and Emotion. 5 (4): 295–310. doi:10.1007/BF00992549. ISSN 0146-7239. S2CID 143844387.

- ^ a b Guerrero, Laura K.; Andersen, Peter A.; Jorgensen, Peter F.; Spitzberg, Brian H.; Eloy, Sylvie V. (1 December 1995). "Coping with the green-eyed monster: Conceptualizing and measuring communicative responses to romantic jealousy". Western Journal of Communication. 59 (4): 270–304. doi:10.1080/10570319509374523. ISSN 1057-0314.

- ^ Salovey, Peter; Rodin, Judith (1 March 1988). "Coping with Envy and Jealousy". Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 7 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1521/jscp.1988.7.1.15. ISSN 0736-7236.

- ^ Bringle, Robert G; Renner, Patricia; Terry, Roger L; Davis, Susan (1 September 1983). "An analysis of situation and person components of jealousy". Journal of Research in Personality. 17 (3): 354–368. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(83)90026-0.

- ^ Guerrero, Laura K.; Trost, Melanie R.; Yoshimura, Stephen M. (1 June 2005). "Romantic jealousy: Emotions and communicative responses". Personal Relationships. 12 (2): 233–252. doi:10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00113.x. ISSN 1475-6811.

- ^ Bevan, Jennifer L.; Lannutti, Pamela J. (1 June 2002). "The experience and expression of romantic jealousy in same-sex and opposite-sex romantic relationships". Communication Research Reports. 19 (3): 258–268. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.613.6096. doi:10.1080/08824090209384854. ISSN 0882-4096. S2CID 38643030.

- ^ Ammon, Rebecca (1 January 2004). "The Influence of Biology and Commitment Beliefs on Jealousy Responses". The Osprey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry. 4.

- ^ Moyano, Nieves; Sánchez-Fuentes, María del Mar; Chiriboga, Ariana; Flórez-Donado, Jennifer (2 October 2017). "Factors associated with Facebook jealousy in three Spanish-Speaking countries" (PDF). Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 32 (3–4): 309–322. doi:10.1080/14681994.2017.1397946. hdl:11323/1608. ISSN 1468-1994. S2CID 148945166.

- ^ Buunk, Bram; Hupka, Ralph B (1987). "Cross-Cultural Differences in the Elicitation of Sexual Jealousy". The Journal of Sexual Research. 23: 12–22. doi:10.1080/00224498709551338.

- ^ Burriss, R., & Little, A. (2006). "Effects of partner conception risk phase of male perception of dominance in faces" (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior. 27 (4): 297–305. Bibcode:2006EHumB..27..297B. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.01.002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gangestad, S. W., Thornhill, R., & Garver, C. E. (2002). "Changes in women's sexual interest and their partner's mate retention tactics across the menstrual cycle: evidence for shifting conflicts of interest". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 269 (1494): 975–82. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1952. PMC 1690982. PMID 12028782.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ammon, Rebecca L. (2004). "The Influence of Biology and Commitment Beliefs on Jealousy Responses". The Osprey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons. All Volumes (2001–2008).

- ^ Rydell, McConnell, Bringle 2004, p. 10.

- ^ "Jealousy". The American Journal of Psychology. 17: 483. 1906.

- ^ Sharpsteen, Don J.; Kirkpatrick, Lee A. (1997). "Romantic jealousy and adult romantic attachment". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 72 (3): 627–640. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.627. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 9120787.

- ^ Haselton, Martie G.; Gangestad, Steven W. (April 2006). "Conditional expression of women's desires and men's mate guarding across the ovulatory cycle". Hormones and Behavior. 49 (4): 509–518. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.10.006. ISSN 0018-506X. PMID 16403409. S2CID 7065777.

- ^ Green, Sabini 2006, p. 11

- ^ Harris, Christine R.; Prouvost, Caroline (23 July 2014). "Jealousy in Dogs". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e94597. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...994597H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094597. PMC 4108309. PMID 25054800.

- ^ "Dog Jealousy: What it is, Why it Happens, and How to Help". The Dog People by Rover.com. 16 May 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Protective, Jealous, and Possessive Behaviors | Sequoia Humane Society". sequoiahumane.org. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Ting, Inga (22 June 2015). "Why dogs attack babies: Unfamiliarity, smell, sound and gaze can contribute". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Ferris, Amber L.; Smith, Sandi W.; Greenberg, Bradley S.; Smith, Stacy L. (13 August 2007). "The Content of Reality Dating Shows and Viewer Perceptions of Dating". Journal of Communication. 57 (3): 490–510. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00354.x. ISSN 0021-9916.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Frampton, Jessica R.; Linvill, Darren L. (31 July 2017). "Green on the Screen: Types of Jealousy and Communicative Responses to Jealousy in Romantic Comedies". Southern Communication Journal. 82 (5): 298–311. doi:10.1080/1041794x.2017.1347701. ISSN 1041-794X. S2CID 149087114.

- ^ a b c d e Croucher, Stephen M.; Homsey, Dini; Guarino, Linda; Bohlin, Bethany; Trumpetto, Jared; Izzo, Anthony; Huy, Adrienne; Sykes, Tiffany (October 2012). "Jealousy in Four Nations: A Cross-Cultural Analysis". Communication Research Reports. 29 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1080/08824096.2012.723273. ISSN 0882-4096. S2CID 144589859.

Further reading

[edit]- Peter Goldie. The Emotions, A Philosophical Exploration . Oxford University Press, 2000

- W. Gerrod Parrott. Emotions in Social Psychology . Psychology Press, 2001

- Jesse J. Prinz. Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotions. Oxford University Press, 2004

- Staff, P.T. (January–February 1994), "A devastating difference", Psychology Today, Document ID 1544, archived from the original on 27 April 2006, retrieved 8 July 2006

- Jealousy among the Sangha Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Quoting Jeremy Hayward from his book on Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa

- Hart, S. L. & Legerstee, M. (Eds.) "Handbook of Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Multidisciplinary Approaches" . Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Pistole, M.; Roberts, A.; Mosko, J. E. (2010). "Commitment Predictors: Long-Distance Versus Geographically Close Relationships". Journal of Counseling & Development. 88 (2): 146. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x.

- Levy, Kenneth N., Kelly, Kristen M Feb 2010; Sex Differences in Jealousy: A Contribution From Attachment Theory Psychological Science, vol. 21: pp. 168–173

- Green, M. C.; Sabini, J. (2006). "Gender, socioeconomic status, age, and jealousy: Emotional responses to infidelity in a national sample". Emotion. 6 (2): 330–334. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565.

- Rauer, A. J.; Volling, B. L. (2007). "Differential parenting and sibling jealousy: Developmental correlates of young adults' romantic relationships". Personal Relationships. 14 (4): 495–511. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00168.x. PMC 2396512. PMID 19050748.

- Pistole, M.; Roberts, A.; Mosko, J. E. (2010). "Commitment Predictors: Long-Distance Versus Geographically Close Relationships". Journal of Counseling & Development. 88 (2): 146. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x.

- Tagler, M. J. (2010). "Sex differences in jealousy: Comparing the influence of previous infidelity among college students and adults". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 1 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1177/1948550610374367. S2CID 143895254.

- Tagler, M. J.; Gentry, R. H. (2011). "Gender, jealousy, and attachment: A (more) thorough examination across measures and samples". Journal of Research in Personality. 45 (6): 697–701. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.08.006.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.