Jim Mattis

James Norman Mattis (born September 8, 1950) is an American military veteran who served as the 26th United States secretary of defense from 2017 to 2019. A retired Marine Corps four-star general, he commanded forces in the Persian Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War.

Mattis was commissioned in the Marine Corps through the Naval Reserve Officers' Training Corps after graduating from Central Washington University. A career Marine, he gained a reputation among his peers for intellectualism and eventually advanced to the rank of general. From 2007 to 2010, he commanded the United States Joint Forces Command and concurrently served as NATO's Supreme Allied Commander Transformation. He was commander of United States Central Command from 2010 to 2013, with Admiral Bob Harward serving as his deputy commander. After retiring from the military, he served in several private sector roles, including as a board member of Theranos.[6]

Mattis was nominated as secretary of defense by president-elect Donald Trump, and confirmed by the Senate on January 20, 2017. As secretary of defense, Mattis affirmed the United States' commitment to defending longtime ally South Korea in the wake of the 2017 North Korea crisis.[7][8] An opponent of proposed collaboration with China and Russia,[9] Mattis stressed what he saw as their "threat to the American-led world order".[10] Mattis occasionally voiced his disagreement with certain Trump administration policies such as the withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal,[11] withdrawals of troops from Syria and Afghanistan,[12] and budget cuts hampering the ability to monitor the impacts of climate change.[13][14] According to The Hill, Mattis also reportedly dissuaded Trump from attempting to assassinate Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria.[15]

On December 20, 2018, after failing to convince Trump to reconsider his decision to withdraw all American troops from Syria, Mattis announced his resignation effective the end of February 2019; after Mattis's resignation generated significant media coverage, Trump abruptly accelerated Mattis's departure date to January 1, 2019, stating that he had essentially fired Mattis.[16]

Early life

[edit]Mattis was born on September 8, 1950, in Pullman, Washington.[17] He is the son of Lucille (Proulx) Mattis[18] and John West Mattis,[19][20] a merchant mariner. His mother immigrated to the United States from Canada as an infant and had worked in Army Intelligence in South Africa during the Second World War.[21] Mattis's father moved to Richland, Washington, to work at a plant supplying fissile material to the Manhattan Project. Mattis was raised in a bookish household that did not own a television.[22][23] He describes "hitchhiking around a lot from the time I was about 12 or 13 to about 20 going into the Marines on active duty."[23]

Mattis graduated from Richland High School in 1968.[22][24] He earned a Bachelor of Arts in history from Central Washington University in 1971[25][26][27] and a Master of Arts in international security affairs from the National War College of National Defense University in 1994.[28]

Marine career

[edit]

Mattis enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in 1969.[29] He was commissioned a second lieutenant through the Naval Reserve Officers' Training Corps on January 1, 1972.[30] During his service years, Mattis was considered an "intellectual" among the upper ranks.[31] Robert H. Scales, a retired United States Army major general, called him "one of the most urbane and polished men I have known."[32] As a lieutenant, Mattis was assigned as a rifle and weapons platoon commander in the 3rd Marine Division. As a captain, he was assigned as the Naval Academy Preparatory School's Battalion Officer, commanded rifle and weapons companies in the 1st Marine Regiment, then served at Recruiting Station Portland, Oregon, as a major.[33] Upon promotion to the rank of lieutenant colonel, Mattis commanded 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, one of Task Force Ripper's assault battalions during the Gulf War.[34] As a colonel, Mattis commanded the 7th Marine Regiment from June 28, 1994, to June 14, 1996.[35]

Mattis is a graduate of the US Marine Corps Amphibious Warfare School, US Marine Corps Command and Staff College, and the National War College. He is noted for his interest in the study of military history and world history,[36][37] with a personal library that once included over 7,000 volumes,[2] and a penchant for publishing required reading lists for Marines under his command.[38][39] He required his Marines to be well-read in the culture and history of regions where they were deployed, and had his Marines deploying to Iraq undergo "cultural sensitivity training".[37] According to an article published in 2004 by the Los Angeles Times it was his concern for the enlisted ranks along with his energy and enthusiasm that garnered him the nickname "Mad Dog".[4][5] But in 2016, when President-elect Trump asked Mattis if his nickname was indeed "Mad Dog," Mattis replied, "No, sir," saying that his actual nickname was "Chaos."[40]

War in Afghanistan

[edit]Mattis led the 1st Marine Expeditionary Brigade as its commanding officer upon promotion to brigadier general.[41] It was as a regimental commander that he earned his nickname and call sign, "CHAOS", an acronym for "Colonel Has Another Outstanding Solution", which was initially somewhat tongue in cheek.[42][23]

During the initial planning for the War in Afghanistan, Mattis led Task Force 58 in operations in the southern part of the country beginning in November 2001,[43] becoming the first Marine Corps officer to command a Naval Task Force in combat.[30] According to Mattis, his objective upon arriving in Afghanistan was to "make sure that the enemy didn't feel like they had any safe haven, to destroy their sense of security in southern Afghanistan, to isolate Kandahar from its lines of communication, and to move against Kandahar".[44] In December 2001, an airstrike carried out by a B-52 bomber inadvertently targeted a position held by US special operations troops and Afghan militiamen in Uruzgan Province. Numerous men were wounded in the incident, but Mattis repeatedly refused to dispatch helicopters from the nearby Camp Rhino to recover them, citing operational safety concerns. Instead, an Air Force helicopter flew from Uzbekistan to ferry the men to the Marine Corps base where helicopters sat readily available but unauthorized to fly. Captain Jason Amerine blamed the delay caused by Mattis's refusal to order a rescue operation for the deaths of several men. Amerine wrote, "Every element in Afghanistan tried to help us except the closest friendly unit, commanded by Mattis," though he also wrote that "none of that was assessed properly because the [5th Special Forces Group] chose not to call for a formal investigation".[45][46] This episode was used against Mattis when he was nominated for defense secretary in 2016.[47]

Mattis describes being presented with the location of Osama bin Laden in December 2001 and creating a plan to kill him that was never executed.[23]

While serving in Afghanistan as a brigadier general, Mattis was known as an officer who engaged his men with "real leadership."[48] A young Marine officer, Nathaniel Fick, said he witnessed Mattis in a fighting hole talking with a sergeant and lance corporal: "No one would have questioned Mattis if he'd slept eight hours each night in a private room, to be woken each morning by an aide who ironed his uniforms and heated his MREs. But there he was, in the middle of a freezing night, out on the lines with his Marines."[49]

Iraq War

[edit]

As a major general, Mattis commanded the 1st Marine Division during the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the Iraq War.[36] Mattis played key roles in combat operations in Fallujah, including negotiation with the insurgent command inside the city during Operation Vigilant Resolve in April 2004, as well as participation in planning of the subsequent Operation Phantom Fury in November.[50]

Wedding bombing

[edit]In May 2004, Mattis ordered the 3 a.m. bombing of what his intelligence section had reported was a suspected enemy safe house near the Syrian border, but was later reported to be a wedding party and allegedly resulted in the deaths of 42 civilians, including 11 women and 14 children. Mattis said it had taken him 30 seconds to decide whether to bomb the location. Describing the wedding as implausible, he said, "How many people go to the middle of the desert to hold a wedding 80 miles (130 km) from the nearest civilization? These were more than two dozen military-age males. Let's not be naive."[51] The occurrence of a wedding was disputed by military officials, but the Associated Press obtained video footage showing a wedding party and a video the next day showed musical instruments and party decoration among the remains.[52] When asked by the press about footage on Arabic television of a child's body being lowered into a grave, he replied: "I have not seen the pictures but bad things happen in wars. I don't have to apologize for the conduct of my men."[53]

Department of Defense survey

[edit]Following a Department of Defense survey that showed only 55% of US soldiers and 40% of Marines would report a colleague for abusing civilians, Mattis told Marines in May 2007 that "whenever you show anger or disgust toward civilians, it's a victory for al-Qaeda and other insurgents." Believing that a need for restraint in war as key to defeating an insurgency, he added: "every time you wave at an Iraqi civilian, al-Qaeda rolls over in its grave."[54]

1st Marine Division's motto "no better friend, no worse enemy"

[edit]Mattis popularized the 1st Marine Division's motto "no better friend, no worse enemy", a paraphrase of the epitaph the Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla wrote for himself,[23][55] in his open letter to all men within the division for their return to Iraq. This phrase later became widely publicized during the investigation into the conduct of Lieutenant Ilario Pantano, a platoon commander serving under Mattis.[56][57][58][59][60]

In the letter Mattis also encouraged his men to "fight with a happy heart," a phrase he attributes to Sitting Bull, and that he learned from the Native American oral tradition.[23]

Cultural sensitivity training

[edit]As his division prepared to ship out, Mattis called in "experts on the Middle East" for "cultural sensitivity training." He constantly toured the battlefield to tell stories of Marines who were able to show "discretion in moments of high pressure." As an apparent example, he encouraged his Marines to grow moustaches to look more like the people they were working with.[37]

Removal of senior leaders

[edit]He was also noted for a willingness to remove senior leaders under his command when the US military seemed unable or unwilling to relieve underperforming or incompetent officers. During the division's push to Baghdad, Mattis relieved Colonel Joe D. Dowdy, commander of Regimental Combat Team-1. It was such a rare occurrence in the modern military that it made the front page of newspapers. Despite this, Mattis declined to comment on the matter publicly other than to say that the practice of officer relief remains alive, or at least "we are doing it in the Marines."[49] Later interviews of Dowdy's officers and men revealed that "the colonel was doomed partly by an age-old wartime tension: Men versus mission—in which he favored his men," while Mattis insisted on execution of the mission to seize Baghdad swiftly.[61]

Combat Development Command

[edit]After being promoted to lieutenant general, Mattis took command of Marine Corps Combat Development Command. In February 2005, speaking at a forum in San Diego, he said, "Actually it's quite fun to fight them, you know. It's a hell of a hoot. It's fun to shoot some people. I'll be right up there with you. I like brawling. You go into Afghanistan, you got guys who slap women around for five years because they didn't wear a veil. You know, guys like that ain't got no manhood left anyway. So it's a hell of a lot of fun to shoot them."[62] Mattis's remarks sparked controversy; General Michael Hagee, commandant of the Marine Corps, issued a statement suggesting Mattis should have chosen his words more carefully, but he would not be disciplined.[63]

US Joint Forces Command

[edit]

The Pentagon announced on May 31, 2006, that Mattis had been chosen to take command of the I Marine Expeditionary Force, based out of Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton.[64] On September 11, 2007, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates announced that President George W. Bush had nominated Mattis for appointment to the rank of general to command US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) in Norfolk, Virginia. NATO agreed to appoint Mattis as Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT). On September 28, 2007, the United States Senate confirmed Mattis's nomination, and he relinquished command of the I MEF on November 5, 2007, to Lieutenant General Samuel Helland.[33]

Mattis was promoted to four-star general and took control of USJFCOM/SACT on November 9, 2007. On September 9, 2009, French Air Force General Stéphane Abrial assumed the position of SACT. Mattis remained commander of JFCOM from November 2007 until September 2010.[65]

As a four-star general, Mattis included a member of the intelligence community on his staff to be in every meeting and "challenge any assumptions we made."[23]

US Central Command

[edit]

In early 2010, Mattis was reported to be on the list of generals being considered to replace James T. Conway as the commandant of the US Marine Corps.[66] In July, he was recommended by Defense Secretary Robert Gates for nomination to replace David Petraeus as commander of United States Central Command (CENTCOM),[17][67] and formally nominated by President Obama on July 21.[68]

Mattis took command at a ceremony at MacDill Air Force Base on August 11.[69][70][71] As head of Central Command, Mattis oversaw the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and was responsible for a region that includes Syria, Iran, and Yemen.[72] He lobbied the Obama administration for a more aggressive response to Iran, including more covert operations and disruption of Iranian arms shipments to Syria and Yemen.[73] After an incident in 2011 where an Iranian jet had attacked a U.S. drone flying over the Persian Gulf in international airspace, Mattis wanted permission to shoot down any Iranian aircraft that was attacking American drones, but the Obama administration denied this request.[74] According to Leon Panetta, the Obama administration did not place much trust in Mattis because he was perceived as too eager for a military confrontation with Iran.[75] Panetta later said, though, that some of the mistrust was unjustified, arising from the inexperience of some White House staff not understanding the need "to look at all of the options that a president should look at in order to make the right decisions." Nevertheless, Mattis's hawkishness was out of step with the White House's perspective, and "ultimately, Mattis’s advocacy and aggressive style alienated the White House and the president he was serving."[76]

Mattis retired in March 2013, and the Defense Department nominated General Lloyd Austin to succeed him.[77] Sheikh Моhamed bin Zayed al-Nahyan asked Mattis to serve as a military advisor in the Yemen war conflict. During Mattis's tenure as the Secretary of Defense under President Trump, his consultation with the UАЕ was omitted from public record and financial disclosure. Mattis's relationship with the UАЕ was strong, featuring a speech in Аbu Dhаbi initially set to be compensated at $100,000 but later clarified as unpaid.[78]

Civilian career

[edit]After retiring from the military, Mattis worked for FWA Consultants and served as a member of the General Dynamics Board of Directors.[79] Between 2013 and 2017, while on the board of General Dynamics, Mattis made more than $900,000 in compensation, including company stock.[80] In August 2013, he was appointed an Annenberg Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution[81] and in 2016 he was named the Davies Family Distinguished Visiting Fellow.[82][23]

In December 2015, Mattis joined the advisory board[83] of Spirit of America, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that provides assistance to support the safety and success of American service personnel and the local people they seek to help.

He is co-editor of the book Warriors & Citizens: American Views of Our Military, published in August 2016.[84]

From 2013 to January 2017, Mattis was a board member of Theranos, a health technology company that claimed to have devised revolutionary blood tests using very small amounts of blood, which was later determined to be a fraudulent claim by the US Securities and Exchange Commission.[85][86][87][88][89] Previously, in mid-2012, a Department of Defense official evaluating Theranos's blood-testing technology for the military initiated a formal inquiry with the Food and Drug Administration about the company's intent to distribute its tests without FDA clearance. In August 2012, Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes asked Mattis, who had expressed interest in testing Theranos's technology in combat areas, to help. Within hours, Mattis forwarded his email exchange with Holmes to military officials, asking "how do we overcome this new obstacle". In July 2013, the Department of Defense gave Mattis permission to join Theranos's board provided he did not represent Theranos with regard to the blood-testing device and its potential acquisition by the Departments of the Navy or Defense.[90]

In 2019, Mattis's book Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead was published.[91] It is an autobiography as well as an argument in favor of an internationalist foreign policy.[92] On August 7, 2019, Mattis was re-elected to the board of General Dynamics.[93]

Secretary of Defense (2017–2019)

[edit]Nomination and confirmation

[edit]

President-elect Donald Trump met with Mattis for a little over one hour in Bedminster, New Jersey, on November 20, 2016.[94] He later wrote on Twitter, "General James 'Mad Dog' Mattis, who is being considered for secretary of defense, was very impressive yesterday. A true General's General!"[95] On December 1, 2016, Trump announced at a rally in Cincinnati that he would nominate Mattis for secretary of defense.[96]

The National Security Act of 1947 requires a seven-year waiting period before retired military personnel can assume the role of secretary of defense; Mattis's nomination meant that it was the first time since 1950 (in that instance for George Marshall) that a waiver of the law was needed.[96][97] The waiver for Mattis passed 81–17 in the Senate and 268–151 in the House. Mattis was subsequently confirmed as secretary of defense by a vote of 98–1 in the United States Senate on January 20, 2017.[98] Senator Kirsten Gillibrand was the sole "no" vote,[99] stating that she was opposed to the waiver on principle,[100] though she would vote to confirm Lloyd Austin for the same position in 2021, having only been out of the Army since 2016.[101]

Tenure

[edit]

In a January 2017 phone call with Saudi Arabia's deputy crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Mattis "reaffirmed the importance of the US–Saudi Arabia strategic relationship".[102]

For his first official trip abroad, Mattis began a two-day visit with longtime US ally South Korea on February 2, 2017.[7] He warned North Korea that "any attack on the United States, or our allies, will be defeated", and any use of nuclear weapons would be met with an "effective and overwhelming" response from the United States.[8] During a press conference in London on March 31, 2017, with the British secretary of state for defence, Michael Fallon, Mattis said North Korea was behaving "in a very reckless manner" and must be stopped.[103] During a Pentagon news conference on May 26, Mattis reported the US was working with the UN, China, Japan, and South Korea to avoid "a military solution" with North Korea.[104] On June 3, Mattis said the United States regarded North Korea as "clear and present danger" during a speech at the international security conference in Singapore.[105] In a June 12 written statement to the House Armed Services Committee Mattis said North Korea was the "most urgent and dangerous threat to peace and security".[106] On June 15, Mattis said the US would win a war against North Korea, but "at great cost".[107]

On March 22, 2017, during questioning from the US Senate, Mattis affirmed his support for US troops remaining in Iraq after the Battle of Mosul was concluded.[108] Mattis responded to critics who suggested the Trump administration had loosened the rules of engagement for the US military in Iraq after US-led coalition airstrikes in Mosul killed civilians,[109] saying, "We go out of our way to always do everything humanly possible to reduce the loss of life or injury among innocent people."[110] According to Airwars, the US-led coalition killed as many as 6,000 civilians in Iraq and Syria in 2017.[111]

On April 5, 2017, Mattis called the Khan Shaykhun chemical attack "a heinous act," and said it would be treated accordingly.[112] On April 10, Mattis warned the Syrian government against using chemical weapons again.[113] The following day, Mattis gave his first Pentagon news conference since becoming secretary of defense, saying ISIL's defeat remained "our priority," and the Syrian government would pay a "very, very stiff price" for further usage of chemical weapons.[114] On April 21 Mattis said Syria still had chemical weapons and was in violation of United Nations Security Council resolutions.[115] According to investigative journalist Bob Woodward, Trump ordered Mattis to assassinate Assad, but Mattis refused.[116] On May 8 Mattis told reporters details of the proposed Syrian safe zones were "all in process right now" and the United States was involved with configuring them.[117]

Mattis voiced support for a Saudi Arabian-led military campaign against Yemen's Shiite rebels.[118] He asked Trump to remove restrictions on US military support for Saudi Arabia.[119]

On April 20, 2017, one week after the Nangarhar airstrike, Mattis told reporters that the US would not conduct a damage assessment "in terms of the number of people killed" in Afghanistan.[120] Mattis traveled to Afghanistan days later and met with government officials, explaining that the purpose of the trip was to allow him to state his recommendations for US strategy in the country.[121] On June 13, Mattis said US forces were "not winning" in Afghanistan and the administration would develop a new strategy by "mid-July" while speaking to the United States Senate Committee on Armed Services.[122] On June 29, Mattis said the Obama administration "may have pulled our troops out too rapidly" and that he intended to submit a new Afghanistan strategy to Trump upon his return to Washington, D.C.[123]

The United States has been openly arming the Syrian Kurdish fighters in the war against ISIL since May 2017.[124] Following the start of the Turkish invasion of northern Syria aimed at ousting US-backed Syrian Kurds from the enclave of Afrin, Mattis said in January 2018: "Turkey is a NATO ally. It's the only NATO country with an active insurgency inside its borders. And Turkey has legitimate security concerns."[125] Turkish Deputy Prime Minister Bekir Bozdağ urged the United States to halt its support for Kurdish YPG fighters, saying: "Those who support the terrorist organization will become a target in this battle."[126]

On April 13, 2018, Mattis briefed reporters in a press conference at the Pentagon on the 2018 missile strikes against Syria being carried out against the Assad regime's chemical weapon compounds, saying, "Tonight, France, the United Kingdom and the United States took decisive action to strike the Syrian chemical weapons infrastructure. Clearly the Assad regime did not get the message last year. This time our allies and we have struck harder. Together we have sent a clear message to Assad and his murderous lieutenants that they should not perpetrate another chemical weapons attack for which they will be held accountable".[127]

In November 2018, the CIA assessed with "high confidence" that Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman ordered the assassination of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.[128] Under mounting pressure from lawmakers who wanted action against Saudi Arabia, Mattis and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a rare closed briefing of the Senate, disputed the CIA's conclusion and declared there was no direct evidence linking the crown prince to Khashoggi's assassination.[129]

Wherever Mattis traveled overseas, he brought the Defense Security Cooperation Agency director (the official in charge of weapon sales to foreign governments), according to Lt. Gen. Charles Hooper, speaking at the Brookings Institution in June 2019.[130]

Conflicts with Trump and resignation

[edit]

Mattis had recommended General David L. Goldfein, Air Force Chief of Staff, to succeed retiring General Joseph Dunford as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in September 2018. Instead, Trump chose General Mark Milley, Army Chief of Staff, whom Mattis had recommended for the position of Supreme Allied Commander Europe.[131][132]

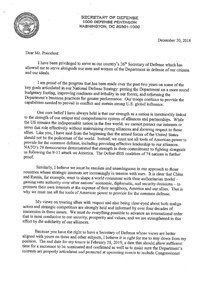

On December 19, 2018, Trump announced immediate US withdrawal from Syria, over his national security advisers' objections.[133] Mattis had recently said that the US would remain in Syria after ISIL's defeat to ensure it did not regroup. The next day, he submitted his resignation after failing to persuade Trump to reconsider.[134][135] His resignation letter contained language that appeared to criticize Trump's worldview—praising NATO, which Trump has often derided, and the 79-nation anti-ISIS coalition that Trump had decided to leave. Mattis also affirmed the need for "treating allies with respect and also being clear-eyed about both malign actors and strategic competitors" and remaining "resolute and unambiguous" against authoritarian states such as China and Russia. He wrote that Trump has "the right to have a Secretary of Defense whose views are better aligned with [his] on these and other subjects."[136][137] His resignation triggered alarm among historical allies.[138] In his 2018 resignation letter, Mattis called both Russia and China "authoritarian models" rivaling US interests.[139] Mattis's letter said his resignation would be effective February 28, 2019.[140] Three days later Trump moved Mattis's departure date up to January 1, after becoming angered by the implicit criticism of Trump's worldview in Mattis's letter.[141] On January 2, 2019, Trump criticized Mattis's performance as secretary of defense and said he had "essentially fired him."[142]

John F. Kelly, Trump's chief of staff when Mattis left his position, denied that Trump fired Mattis or asked for his resignation. He said Trump must be confused or mistaken, and that "Jim Mattis is an honorable man."[143] Mattis returned to his post as Davies Family Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution. [144]

Post-tenure

[edit]After leaving the White House, Mattis initially declined to offer his opinion of the Trump administration, saying, "If you leave an administration, you owe some silence,"[145] and was guarded when asked to reflect on Trump or military matters, saying he didn't want to detract from the troops.[146] He changed his position after becoming "angry and appalled" about the events leading up to the violent treatment of noncombative protesters near the White House on June 1, 2020, for the purpose of a photo op for Trump at the church across Lafayette Square.[147] Trump responded by Twitter that evening that he "felt great" he had previously asked Mattis to resign, and he didn't like much about Mattis or his "leadership style" and was "Glad he is gone!"[146]

In 2019, Mattis joined The Cohen Group as senior counsel.[148][149][150]

Mattis, along with all other living former secretaries of defense, ten in total, published a Washington Post op-ed piece in January 2021 telling President Trump not to involve the military in determining the outcome of the 2020 elections.[151]

Al Smith Dinner comments

[edit]At the October 17, 2019, Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, Mattis, the keynote speaker, responded to comments Trump had made about him, saying,

I'm not just an overrated general, I am the greatest, the world's most overrated ... I'm honored to be considered that by Donald Trump, because he also called Meryl Streep an overrated actress. So I guess I'm the Meryl Streep of generals, and frankly, that sounds pretty good to me. And you do have to admit that between me and Meryl, at least we've had some victories.[152]

He continued, "I've earned my spurs on the battlefield ... Donald Trump earned his spurs in a letter from a doctor."[153]

Political positions

[edit]Mattis claimed he has "never registered for any political party". He also claimed when he was 18 that he was "proudly apolitical".[154]

Mattis said in 2020 that Donald Trump is "the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people — does not even pretend to try. Instead he tries to divide us." After the January 6 attack, Mattis said Trump used the presidency to "destroy trust in our election and to poison our respect for fellow citizens." In 2024, after former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley called Trump "fascist to the core" and "the most dangerous person ever," author Bob Woodward said Mattis had emailed him to second Milley's assessment.[155]

Israeli–Palestinian peace process

[edit]Mattis supports a two-state solution model for Israeli–Palestinian peace. He has said the situation in Israel is "unsustainable" and that Israeli settlements harm prospects for peace and could lead to an apartheid-like situation in the West Bank.[156] In particular, he has said that the perception of biased American support for Israel has made it difficult for moderate Arabs to show support for the United States. Mattis strongly supported Secretary of State John Kerry on the Middle East peace process, praising Kerry for being "wisely focused like a laser beam" on a two-state solution.[157]

Iran and Middle Eastern allies

[edit]

Mattis believes Iran is the principal threat to the stability of the Middle East, ahead of Al-Qaeda and ISIL. Mattis says: "I consider ISIS nothing more than an excuse for Iran to continue its mischief. Iran is not an enemy of ISIS. They have a lot to gain from the turmoil in the region that ISIS creates." Mattis sees the Iran nuclear deal as a poor agreement, but believes there is now no way to tear it up, saying: "We are just going to have to recognize that we have an imperfect arms control agreement. Second, that what we achieved is a nuclear pause, not a nuclear halt". Mattis argues that inspections may fail to prevent Iran from seeking to develop nuclear weapons, but that "[i]f nothing else at least we will have better-targeting data if it comes to a fight in the future."[11] Additionally, he criticized Obama for being "naive" about Iranian intentions and Congress for being "pretty much absent" on the nuclear deal.[158]

Mattis praises the friendship of regional US allies such as Jordan, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates.[159][160][161] He also criticized Obama for seeing allies as "freeloading", saying: "For a sitting US President to see our allies as freeloaders is nuts."[161] He has cited the importance of the United Arab Emirates and Jordan as countries that wanted to help, for example, in filling in the gaps in Afghanistan. He criticized Obama's defense strategy as giving "the perception we're pulling back" from US allies.[162] He stresses the need for the US to bolster its ties with allied intelligence agencies, particularly those of Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.[163] In 2012, Mattis argued for providing weapons to Syrian rebels as a way to fight back against Iranian proxies in Syria.[164]

Japan

[edit]Mattis visited Japan one week after being sworn in as secretary of defense. During a meeting with Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, Mattis emphasized that the US remains committed to the mutual defense of Japan and stated, "I want there to be no misunderstanding during the transition in Washington that we stand firmly, 100 percent, shoulder to shoulder with you and the Japanese people."[165] He also reassured Japan that the US would defend the disputed Senkaku Islands controlled by Japan but also claimed by China and Taiwan.[166]

Russia

[edit]Speaking at a 2015 conference sponsored by The Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C., Mattis said he believed that Russian President Vladimir Putin's intent is "to break NATO apart."[167] Mattis has also spoken out against what he perceives as Russia's expansionist or bellicose policies in Syria, Ukraine and the Baltic states.[168] In 2017, Mattis said that the world order is "under the biggest attack since World War II, ... and that is from Russia, from terrorist groups, and with what China is doing in the South China Sea.[169]

On February 16, 2017, Mattis said the United States was not currently prepared to collaborate with Russia on military matters, including future anti-ISIL US operations.[9] In August 2017, he said: "Despite Russia's denials, we know they are seeking to redraw international borders by force, undermining the sovereign and free nations of Europe".[170]

On July 1, 2022, he described the Russian invasion of Ukraine as "immoral, the tactically incompetent, operationally stupid and strategically foolish effort". He added that Vladimir Putin "probably thought that the Ukrainian people were going to welcome him."[171]

China

[edit]Mattis called for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and criticized China's island-building activities, saying: "The bottom line is ... the international waters are international waters."[172]

Climate change

[edit]In 2017, Mattis said that budget cuts would hamper the ability to monitor the effects of global warming,[13] and noted, "climate change is a challenge that requires a broader, whole-of-government response."[173] He also told senators "climate change is impacting stability in areas of the world where our troops are operating today."[174]

2020 George Floyd protests

[edit]On June 3, 2020, Mattis issued a statement to The Atlantic in which he criticized President Donald Trump and his policies during the George Floyd protests. He berated Trump for deliberately trying to cause division among the American people and advocating military action to "dominate" the country's protests. "Militarizing our response, as we witnessed in Washington, D.C., sets up a conflict—a false conflict—between the military and civilian society, and diminishes the trust and constitutional relationship between the armed services and the civilian population they support", he wrote. Mattis called for reunification among the people, regardless of the president, to preserve the welfare of society, and its future.[147]

Mattis wrote that Trump was "the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people—does not even pretend to try. Instead, he tries to divide us". He added that America is "witnessing the consequences of three years without mature leadership". He called for accountability for "those in office who would make a mockery of our Constitution." He concluded, "Only by adopting a new path—which means, in truth, returning to the original path of our founding ideals—will we again be a country admired and respected at home and abroad."[175][147][176][177]

Personal life

[edit]A bachelor for his entire professional career, a now-retired Mattis married physicist and business executive Christina Lomasney[178] in June 2022.[179] He has no children.[2] He previously proposed to a woman, but she called off the wedding three days before it was to occur, after colleagues talked him out of leaving the Marine Corps for her.[22][180] He was nicknamed "The Warrior Monk" because of his bachelorhood and lifelong devotion to the study of war.[181] An avid reader, he has 7,000 books in his private library,[182] and has recommended Marcus Aurelius's Meditations as the one book every American should read.[183] Mattis describes Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers as one of the reasons for implementing training simulators for infantrymen.[23]

Mattis was inducted into the Sons of the American Revolution on July 13, 2021.

Mattis is a Catholic, and has been described as "devout"[184] and "committed".[185] During the 2003 Iraq invasion, he often prayed with general John F. Kelly on Sundays.[184] The Trump transition team's formal biography of Mattis described him as "the living embodiment of the Marine Corps motto, Semper Fidelis."[185] He has declined when asked by reporters to discuss his faith in public.[186] In a 2003 PBS interview, Mattis recalled how his Marines followed advice from his chaplain on gaining the support of Iraqi citizens:

On the suggestion of my Catholic chaplain the Marines would take chilled drinking water in bottles and walk out amongst the protesters and hand it out. It is just hard to throw a rock at somebody who has given you a cold drink of water and it's 120 degrees outside.[185]

Military awards

[edit]Mattis's decorations, awards, and badges include, among others:

| | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| |||||||

Meritorious Service Cross citation

[edit]

"While occupying key leadership positions within the United States Armed Forces and NATO between 2001 and 2012, General Mattis directly and repeatedly contributed to the Canadian Forces’ operational success in Afghanistan. Providing unprecedented access and championing Canadian participation in critical policy and training events, he helped shape Canadian counter-insurgency doctrine. Demonstrating unequivocal support and unwavering commitment to Canada, General Mattis has significantly strengthened Canadian-American relations and has been a critical enabler in both countries’ shared achievements in Afghanistan."[187]

Civilian awards

[edit]

Mattis's civilian awards include:

- 2009: Center for National Policy's Edmund S. Muskie Distinguished Public Service Award[17]

- 2010: Atlantic Council's Distinguished Military Leadership Award[17]

- 2013: World Affairs Council of Greater Hampton Roads "Ryan C. Crocker Global Citizen of the Year" Award[79]

- 2014: Marine Corps University Foundation Semper Fidelis Award[79]

- 2014: Washington College honorary doctor of laws degree[188]

- 2016: Washington Policy Center Champion of Freedom Award recipient[189]

- 2021: Elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[190]

- 2021: Honorary Companion of the Order of Australia[191]

In popular culture

[edit]- Mattis is the primary subject of Guy Snodgrass's 2019 book Holding the Line: Inside Trump's Pentagon with Secretary Mattis.[192]

- Robert John Burke portrays Mattis in the 2008 HBO miniseries Generation Kill, which depicts the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[193]

- Mattis is also known for the Internet meme depicting him as "Saint Mattis of Quantico, Patron Saint of Chaos".[194]

- Mattis is commonly "reported on" by the military satire website Duffel Blog for potentially being fired,[195] winning an "arms race" with Russia,[196] and crossing the Potomac to launch a Roman-style coup d'état.[197]

- Mattis is an avid reader and releases his reading lists.[198]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Copp, Tara (October 17, 2018). "'Mr. Secretary, Are You a Democrat?'". Military Times. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Kovach, Gretel C. (January 19, 2013). "Just don't call him Mad Dog". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

He is a lifelong bachelor with no children, but wouldn't move into a monastery unless it was stocked with "beer and ladies."

- ^ a b Boot, Max (March 2006). "The Corps should look to its small-wars past". Armed Forces Journal. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

Mattis, who made a name for himself commanding troops in Afghanistan and Iraq (actually several names — he's known to the troops as the 'Warrior Monk' and 'Mad Dog Mattis')...

- ^ a b Evon, Dan (June 4, 2020). "Did Trump Give Mattis the Nickname 'Mad Dog'?". Snopes. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

The general, who reportedly hates this nickname, has been referred to as 'Mad Dog Mattis' in public reports since at least 2004. Los Angeles Times reported that the nickname originated with Mattis's troops:

- ^ a b Perry, Tony (April 16, 2004). "Marines' 'Mad Dog Mattis' Battles for Iraqis' Support". Los Angeles Times. p. 108. Retrieved June 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

A man of average size and height, Mattis lacks the physical presence of some Marine officers. Nor is he an orator of note. But he is known for his concern for the enlisted ranks and unflagging confidence in his troops. Behind his back troops call him 'Mad Dog Mattis,' high praise in Marine culture.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew (March 16, 2018). "James Mattis is linked to a massive corporate fraud and nobody wants to talk about it". Vox. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ a b "James Mattis, in South Korea, Tries to Reassure an Ally". The New York Times. February 2, 2017. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "US warns North Korea against nuclear attack". Al Jazeera. February 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017.

- ^ a b Baldor, Lolita (February 16, 2017). "Mattis: US not ready to collaborate militarily with Russia". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, David (December 21, 2018). "Donald Trump disputes departing Defense Secretary Jim Mattis over Russia, China". USA Today. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ a b McIntyre, Jamie (April 22, 2016). "Mattis: Iran is the biggest threat to Mideast peace". Washington Examiner. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Ewing, Philip (December 20, 2018). "Defense Secretary Mattis Resigns Amid Syria And Afghanistan Tension". NPR.org. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ a b "Secretary of Defense James Mattis: The Lone Climate Change Soldier in this Administration's Cabinet". Union of Concerned Scientists. 2017.

- ^ "Climate change, extreme weather already threaten 50% of U.S. military sites". USA Today. January 31, 2018.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (September 15, 2020). "Trump says he wanted to take out Syria's Assad but Mattis opposed it". TheHill. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (January 2, 2019). "Trump Says Mattis Resignation Was 'Essentially' a Firing, Escalating His New Front Against Military Critics". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Nominations before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Second Session, 111th Congress" (PDF). US Government Printing Office. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ "Lucille Mattis Obituary". The Tri-City Herald. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ "10 Things You Didn't Know About James Mattis". Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "James Mattis Fast Facts". CNN Library. December 26, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "Reflections with General James Mattis – Conversations with History". University Of California Television. June 5, 2014. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c "James Mattis, a Warrior in Washington". The New Yorker. May 29, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Interview with Jim Mattis". Interviews with Max Raskin. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Kraemer, Kristin M. (November 22, 2016). "Gen. Mattis, Trump's possible defense chief, fulfills Benton County jury duty". Tri-City Herald.

- ^ Ray, Michael (December 2, 2016). "James Mattis". Britannica. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Baldor, Lolita C. (December 2, 2016). "Trump to nominate retired Gen. James Mattis to lead Pentagon". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ "Official website". United States Joint Forces Command. Archived from the original on February 2, 2001. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

- ^ "James N. Mattis – Donald Trump Administration". Office of the Secretary of Defense – Historical Office. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Mattis, James (September 25, 2013). General James Mattis, "In the Midst of the Storm: A US Commander's View of the Changing Middle East". Dartmouth College. Event occurs at 80:10. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Nicholas E. (2005). Basrah, Baghdad and Beyond. US Naval Institute Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-59114-717-6. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Ricks, Thomas E. (August 1, 2006). "Fiasco". Armed Forces Journal. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Proser, Jim (August 15, 2017). "James Mattis: No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy". Nationalreview. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Gen James N. Mattis". Military Hall of Honor. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ Lowry, Richard (December 9, 2016). "Op-ed: General James N. Mattis – A Marine for the History Books". American Military News. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "1ST MARINE DIVISION AND ITS REGIMENTS" (PDF). www.usmcu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Ricks, Thomas E. (2006). Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin Press. p. 313.

- ^ a b c Dickerson, John (April 22, 2010). "A Marine General at War". Slate. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017.

- ^ "LtGen James Mattis' Reading List". Small Wars Journal. June 5, 2007.

- ^ Ricks. Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. p. 317.

- ^ "Woodward, Bob. Rage. Simon & Schuster. 2020, p. 4."

- ^ Walker, Mark (June 2, 2006). "Mattis to assume command of I MEF". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ Wolf, McKenzie (September 21, 2017). "The origin of Mattis' call sign, 'Chaos'". Marine Corps Times. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ Finkel, Gal Perl (December 12, 2016). "General Mattis: A warrior diplomat". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

- ^ Barzilai, Yaniv (January 31, 2014). 102 Days of War: How Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda & the Taliban Survived 2001. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 45ff. ISBN 978-1-61234-534-5.

- ^ Tritten, Travis J. (December 2, 2016). "Retired Green Beret says Mattis left 'my men to die' in Afghanistan". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Vladimirov, Nikita (December 2, 2016). "Former Special Forces officer: Mattis 'betrayed his duty to us'". The Hill. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Meek, James Gordon; Ferran, Lee (December 6, 2016). "Men Left 'to Die': Gen. James Mattis' Controversial Wartime Decision". ABC News. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Ricks, Thomas E. (November 22, 2016). "A SecDef nominee at war?: What I wrote about General Mattis in 'The Generals'". Foreign Policy. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Ricks, Thomas E. (2012). The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today. New York: Penguin Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-59420-404-3.

- ^ Szoldra, Paul (December 1, 2006). "19 unforgettable quotes from legendary Marine Gen. James 'Mad Dog' Mattis". Business Insider. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ West, Bing (2008). The Strongest Tribe: War, Politics, and the Endgame in Iraq. New York, NY: Random House. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-4000-6701-5.

- ^ "Iraq Wedding-Party Video Backs Survivors' Claims". Fox News. May 24, 2004. Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "US soldiers started to shoot us, one by one". The Guardian. May 20, 2004.

- ^ Perry, Tony (May 17, 2007). "General Urges Marines To Add A Friendly Wave To Their Arsenal". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Durant, Will (2001). Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 131. ISBN 0-7432-2910-X.

- ^ "Top 10 Stories of 2005: Pantano, roads, Olchowski are 10–7". Star News Online. December 28, 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Quinn-Judge, Paul (February 28, 2005). "Did He Go Too Far?". Time. Archived from the original on March 4, 2005. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Phillips, Stone (April 26, 2005). "Marine charged with murders of Iraqis: Lieutenant claims self-defense in shooting of detainees". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (November 16, 2005). "Marine acquitted in Iraqi shootings will publish a book". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved January 24, 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Walker, Mark (July 1, 2006). "Pantano case has parallels to Hamdania incident". North County Times. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Cooper, Christopher (April 5, 2004). "How a Marine Lost His Command In Race to Baghdad". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ "General: It's 'fun to shoot some people'". CNN. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Guardiano, John R. (February 11, 2005). "Breaking the Warrior Code". The American Spectator. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Lowe, Christian (June 12, 2006). "Popular commander to lead I MEF". Marine Corps Times. p. 24.

- ^ a b c "French general assumes command of Allied Command Transformation". Allied Command Transformation Public Affairs Office. USS George Washington (CVN-73): NATO. September 18, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Gearan, Anne (June 22, 2010). "Gates announces nomination of Amos for CMC". Marine Corps Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ Cavallaro, Gina (July 8, 2010). "Pentagon picks Mattis to take over CENTCOM". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ "Obama backs Mattis nomination for CENTCOM". Marine Corps Times. July 22, 2010. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ "Mattis takes over Central Command, vows to work with Mideast allies in Afghanistan, Iraq". Fox News. Associated Press. August 11, 2010. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Robbyn (August 12, 2010). "Mattis takes over as CentCom chief". St. Petersburg Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mattis assumes command of CENTCOM". US Central Command. August 11, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mattis interview: Syria would fall without Iran's help". USA Today. April 12, 2013. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg; Ryan, Missy (March 28, 2015). "Why the chaos in Yemen could force Obama to take a harder line with Iran". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Bergen, Peter (May 17, 2022). The Cost of Chaos: The Trump Administration and the World. Penguin. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-593-65289-3.

- ^ Panetta, Leon. Worthy Fights: A Memoir of Leadership in War and Peace (Kindle ed.). Penguin Group. pp. Kindle Locations 6368–6370.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg; Entous, Adam (January 8, 2017). "As a general, Mattis urged action against Iran. As a defense secretary, he may be a voice of caution". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Austin will be nominated to lead US Central Command". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Whitlock, Craig; Jones, Nate (February 6, 2024). "Mattis secretly advised Arab monarch on Yemen war, records show". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c "About General James Mattis". FWA Consultants. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Asher-Schapiro, Avi (December 2, 2016). "Donald Trump Pentagon Pick Mattis Made Nearly $1,000,000 On Board Of Defense Contractor". International Business Times. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ "General James Mattis, Annenberg Distinguished Visiting Fellow". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ "General James Mattis". Hoover Institution. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ Mattis, James (December 9, 2015). "Why I'm Joining Spirit of America". Spirit of America. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ Mattis, James; Schake, Kori, eds. (August 2016). Warriors and Citizens: American Views of Our Military. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution. ISBN 978-0-8179-1934-4. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "SEC.gov | Theranos, CEO Holmes, and Former President Balwani Charged With Massive Fraud". www.sec.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Carreyrou, John (May 21, 2018). Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5247-3166-3.[page needed]

- ^ Levine, Matt (March 14, 2018). "The Blood Unicorn Theranos Was Just a Fairy Tale". Bloomberg View. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Weaver, Christopher (January 5, 2017). "Trump Defense Nominee James Mattis Resigns From Theranos Board". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "A singular board at Theranos". Fortune. June 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Carolyn Y. (December 2, 2015). "E-mails reveal concerns about Theranos's FDA compliance date back years". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Brooks, Risa (August 30, 2019). "Jim Mattis Tells His Life Story". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey. "Why Did James Mattis Resign ...." The Atlantic. October 2019. August 29, 2019.

- ^ "General Dynamics Elects Jim Mattis to Board of Directors". www.gd.com. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ Mattingly, Phil (November 20, 2016). "Trump: 'Mad Dog' Mattis is a 'very impressive' candidate for defense secretary". CNN. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ Trump, Donald J. [@realDonaldTrump] (November 20, 2016). "General James "Mad Dog" Mattis, who is being considered for Secretary of Defense, was very impressive yesterday. A true General's General!" (Tweet). Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2016 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Lamothe, Dan (December 1, 2016). "Trump has chosen retired Marine Gen. James Mattis for secretary of defense". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Lamothe, Dan (December 1, 2016). "How Trump picking Mattis as Pentagon chief breaks with 65 years of U.S. history". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ "Senate confirms retired Gen. James Mattis as defense secretary, breaking with decades of precedent". The Washington Post. January 20, 2017.

- ^ Peterson, Kristina; Hughes, Siobhan (January 20, 2017). "Senate Confirms James Mattis as Defense Secretary". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Schor, Elana (January 20, 2017). "Gillibrand says she won't vote for Mattis waiver". Politico. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

While I deeply respect General Mattis's service, I will oppose a waiver. Civilian control of our military is a fundamental principle of American democracy, and I will not vote for an exception to this rule.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 117th Congress - 1st Session".

- ^ "Readout of Secretary Mattis' Call with Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's Deputy Crown Prince and Minister of Defense Mohammed bin Salman". US Department of Defense. January 31, 2017. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Alexander; Joselow, Gabe (March 31, 2017). "Defense Sec. James Mattis: North Korea 'Has Got to Be Stopped'". NBC News. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ "James Mattis says a military solution in North Korea will 'be tragic on an unbelievable scale'". Business Insider. May 26, 2017.

- ^ Stewart, Phil; Brunnstrom, David (June 3, 2017). "Defense Secretary Mattis turns up heat on North Korea and China". CBS News. Reuters.

- ^ Ali, Idrees; Stone, Mike (June 13, 2017). "North Korea 'most urgent' threat to security: Mattis". Reuters.

- ^ Lockie, Alex (June 16, 2017). "Defense Secretary Mattis explains what war with North Korea would look like". Business Insider.

- ^ Shane III, Leo (March 22, 2017). "Mattis: Expect U.S. troops in Iraq even after ISIS falls". Military Times.

- ^ "After civilians killed in Mosul, Pentagon denies loosening rules". Reuters. March 27, 2017.

- ^ Zenko, Micah (April 11, 2017). "Civilian casualties are up and Congress is AWOL". Foreign Policy. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Ryan, Missy (January 18, 2018). "Civilian deaths tripled in U.S.-led campaign against ISIS in 2017, watchdog alleges". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018.

- ^ Muñoz, Carlos (April 5, 2017). "Defense Secretary Mattis condemns 'heinous' chemical attack in Syria, DoD mulls response". Washington Times.

- ^ "Statement by Secretary of Defense James Mattis on the U.S. Military Response to the Syrian Government's Use of Chemical Weapons" (Press release). United States Department of Defense. April 10, 2017.

- ^ Klimas, Jacqueline (April 11, 2017). "Mattis: U.S. Syria policy is still to defeat ISIS". Politico.

- ^ Burns, Robert (April 21, 2017). "US Defense Sec'y Mattis: Syria still has chemical weapons". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017.

- ^ "Trump wanted Syria's Assad assassinated, Bob Woodward claims in extraordinary new book". Independent. April 9, 2018. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, Ellen (May 8, 2017). "Mattis: Questions unanswered on Syria cease-fire plan". The Hill.

- ^ "Pentagon Weighs More Support for Saudi-led War in Yemen". Foreign Policy. March 26, 2017.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen; Ryan, Missy (March 26, 2017). "Trump administration weighs deeper involvement in Yemen war". The Washington Post.

- ^ Klimas, Jacqueline (April 20, 2017). "Mattis: U.S. won't dig into 'mother of all bombs' damage in Afghanistan". Politico.

- ^ Cullinane, Susannah; Browne, Ryan (March 27, 2017). "US Defense Secretary Mattis visits Afghanistan". CNN.

- ^ O'Brien, Connor (June 13, 2017). "Mattis: 'We are not winning in Afghanistan'". Politico.

- ^ "Mattis says US 'may have pulled our troops out too rapidly' in Afghanistan". Fox News. June 29, 2017.

- ^ Fryer-Biggs, Zachary (January 22, 2018). "Turkish Forces Bomb Key U.S. Ally In Fight Against ISIS In Syria". Newsweek. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Turkey has legitimate security concerns: Mattis". Hürriyet Daily News. Andalou Agency. January 22, 2018. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Turkey to US: Stop YPG support or face 'confrontation'". Al Jazeera. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018.

- ^ "Briefing by Secretary Mattis on U.S. Strikes in Syria". www.defense.gov. April 13, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Hirsh, Michael; Gramer, Robbie (December 4, 2018). "White House Digs Itself in Deeper on Khashoggi". Foreign Policy.

- ^ "Trump administration defends close Saudi ties as Senate moves to end US support for Yemen war". CNBC. November 28, 2018.

- ^ "How Security Cooperation Advanced US Interests". Brookings Institution. June 4, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Hirsh, Michael (December 20, 2018). "Mattis Quits Over Differences With Trump". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ Lamothe, Dan (August 5, 2020). "Gen. David Goldfein, bypassed to be Trump's top military adviser, retires". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Ewing, Philip (December 20, 2018). "Defense Secretary Mattis To Retire In February, Trump Says, Amid Syria Tension". NPR. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Wamsley, Laurel (December 19, 2018). "White House Orders Pentagon To Pull U.S. Troops From Syria". NPR. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

The troop withdrawal is a reversal of policy discussed as recently as this month by Mattis, who said that after the defeat of ISIS, U.S. forces would remain in Syria to prevent a resurgence of the terrorist group and to counteract Iran.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (December 20, 2018). "Jim Mattis Resigns, Rebuking Trump's Worldview". The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (December 8, 2018). "Jim Mattis, Defense Secretary, Resigns in Rebuke of Trump's Worldview". The New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg; Demirjian, Karoun (December 20, 2018). "'A sad day for America': Washington fears a Trump unchecked by Mattis" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri (December 21, 2018). "Mattis Resignation Spreads Alarm in Washington and Abroad". Financial Times. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ "James Mattis' resignation letter in full". BBC News. December 21, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (December 20, 2018). "Jim Mattis, Marine General Turned Defense Secretary, Will Leave Pentagon in February". The New York Times. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (December 23, 2018). "Trump, Angry Over Mattis's Rebuke, Removes Him 2 Months Early". The New York Times. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (January 2, 2019). "Trump Says Mattis Resignation Was 'Essentially' a Firing, Escalating His New Front Against Military Critics". New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Gregorian, Dareh; Hunt, Kasie; Tsirkin, Julie (June 5, 2020). "'Stunning,' 'powerful,' 'overdue': Romney, Murkowski praise Mattis' stinging Trump rebuke". CBSNEWS. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ See "Former Secretary Of Defense, General Jim Mattis, US Marine Corps (Ret.), Returns To The Hoover Institution At Stanford University" online press release March 19, 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Zachary (August 29, 2019). "How James Mattis and Donald Trump's relationship has changed since the Secretary of Defense left his post". CNN. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Martin, Jeffery (June 4, 2020). "Esper Flipflops and Leaves Troops in DC as Trump Spars With Mattis". Newsweek. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Barbara Starr; Paul LeBlanc (June 3, 2020). "Mattis tears into Trump: 'We are witnessing the consequences of three years without mature leadership'". CNN.

- ^ Klar, Rebecca (September 8, 2019). "Mattis joining Cohen Group as senior counselor". The Hill. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Sisk, Richard (September 9, 2019). "Mattis Joins Advisory Group Run by Former Defense Secretary". Military.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Scarborough, Rowan (November 25, 2020). "Mattis failed to disclose role with global consultant tied to China in bombshell column". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "All 10 living former defense secretaries: Involving the military in election disputes would cross into dangerous territory". Washington Post. January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Segers, Grace (October 18, 2019). "Jim Mattis fires back at President Trump for "overrated" insult". CBS News.

- ^ Hauser, Christine (October 17, 2019). "Mattis Mocks Trump's Bone Spurs and Love of Fast Food". The New York Times.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (October 16, 2018). "Defense Secretary Mattis: 'I've never registered for any political party'". CNBC. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Tim (October 17, 2024). "Mattis Told Woodward He Agreed Trump Was a Uniquely Dangerous Threat". The Bulwark.

- ^ Cortellessa, Eric (November 20, 2016). "Trump's top Pentagon pick said settlements were creating 'apartheid'". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016.

- ^ Berman, Lazar (July 25, 2013). "Ex-US general: We pay a price for backing Israel". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016.

- ^ Shane III, Leo (April 22, 2016). "General Mattis wants Iran to be a top focus for the next president (whoever it is)". Military Times. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Cronk, Terri Moon (April 21, 2017). "Mattis Praises America's Security Partnership With Israel". Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Cronk, Terri Moon (April 26, 2018). "Mattis, Israeli Counterpart Discuss Mutual Security Concerns". Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ a b Seck, Hope Hodge (April 22, 2016). "Mattis: 'I Don't Understand' Speculation about Presidential Run". military.com. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Grady, John (May 14, 2015). "Mattis: U.S. Suffering 'Strategic Atrophy'". USNI News. US Naval Institute. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Muñoz, Carlo (April 22, 2016). "James Mattis, retired Marine general, says Iran nuclear deal 'fell short'". The Washington Times. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Ackerman, Spencer (March 6, 2012). "Military's Mideast Chief Sounds Ready to Aid Syria's Rebels". Wired. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Rich, Motoko (February 3, 2017). "James Mattis Says U.S. Is 'Shoulder to Shoulder' With Japan". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Flood, Rebecca (February 4, 2017). "China accuses US of putting regional stability at risk over backing of Japan in island dispute". The Independent. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017.

- ^ "General stating Russian aggression in Ukraine "much more severe" than U.S. treats it may become Defense Secretary". UNIAN. Reuters. November 19, 2016. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Schmitt, Eric (December 1, 2016). "James Mattis, Outspoken Retired Marine, Is Trump's Choice as Defense Secretary". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Stenographic Transcript Before the Committee on Armed Services United States Senate to Conduct a Confirmation Hearing On The Expected Nomination Of Mr. James N. Mattis To Be Secretary Of Defense" (PDF). January 12, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ "James Mattis says Russia wants to use violence to redraw the borders of Europe". Newsweek. August 25, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ ""We're watching Russia wither before our eyes," former US defense chief says". CNN. July 1, 2022.

- ^ Hunt, Katie (January 13, 2017). "Chinese state media slams Tillerson over South China Sea". CNN Politics. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "US Defence Secretary James Mattis says climate change is already destabilizing the world". The Independent. 2017. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022.

- ^ Ness, Erik "The Cost of Skepticism," Brown Alumni Monthly, March/April 2018, p.16

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (June 3, 2020). "James Mattis Denounces President Trump, Describes Him as a Threat to the Constitution". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "READ: Former Defense Secretary Mattis' statement on Trump and protests". CNN. June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Lamothe, Dan (June 4, 2020). "Jim Mattis blasts Trump in message that defends protesters, says president 'tries to divide us'". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Christina Lomasney, biography, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, accessed 2022-07-01

- ^ Schlosser, Kurt (June 28, 2022). "Tech vet and physicist Christina Lomasney marries James Mattis, retired general and ex-defense chief". GeekWire. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (June 28, 2022). "James Mattis just got married in the most Marine way possible". Task & Purpose. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ North, Oliver (July 9, 2010). "Gen. Mattis: The Warrior Monk". Fox News Insider. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House, Simon and Schuster, 2019, p. 50

- ^ Szoldra, Paul (September 26, 2018). "Mattis says every American should read this one book". Business Insider. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Jaffe, Greg; deGrandpre, Andrew (July 28, 2017). "In John Kelly, Trump gets a plain-spoken disciplinarian as his chief of staff". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Trump's Catholic Warriors". National Catholic Register. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ "Mattis Shows How to Handle a Reporter's Question About His Religious Beliefs". Foreign Policy. December 4, 2017. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

That's something I stay pretty private about.

- ^ a b "Meritorious Service Decorations". Canada Gazette. April 27, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Convocation Will Honor Marine General James Mattis". Washington College. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ "WPC's 2016 'Champion of Freedom' named Secretary of Defense". Washington Policy Center. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ "New Members". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Order of Australia - Honorary Appointment - General James Mattis (Retd)". Federal Register of Legislation. December 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Snodgrass, Guy (2019). Holding the Line: Inside Trump's Pentagon with Secretary Mattis. Penguin. ISBN 978-0593084373.

- ^ "Maj. Gen. James 'Maddog' Mattis". HBO.

- ^ Szoldra, Paul (December 2, 2016). "The Facebook page for Marine Special Ops posted a picture of 'Mad Dog' Mattis as a saint". Business Insider. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ Sharpe, Paul (September 24, 2018). "Mattis says he's 'absolutely not' leaving Pentagon while carrying cardboard box out to his car". Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Astronaut, Cat (March 2, 2017). "'We're winning this arms race,' Mattis says during workout at Kremlin gym". Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Scuttlebutt, Dick (December 24, 2013). "General Mattis Crosses Potomac With 100,000 Troops; President, Senate Flee City". Duffel Blog. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Macias, Amanda (September 15, 2018). "The extraordinary reading habits of Defense Secretary James Mattis". CNBC. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

Works cited

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.- Reynolds, Nicholas E. (2005). Basrah, Baghdad and Beyond: The U.S. Marine Corps in the Second Iraq War. p. 5. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-717-4

External links

[edit]- Quotes from James Mattis on All Views by Quotes

- James Mattis Sworn in As US Secretary of Defense

- Department of Defense biography

- Official Marine Corps biography

- "Full transcript: Defense Secretary James Mattis' interview with The Islander". June 2017. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1950 births

- United States Marine Corps personnel of the Gulf War

- United States Marine Corps personnel of the Iraq War

- United States Marine Corps personnel of the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

- American people of Canadian descent

- Atlantic Council

- Catholics from Washington (state)

- Central Washington University alumni

- Hoover Institution people

- Living people

- Military personnel from Washington (state)

- National War College alumni

- People from Pullman, Washington

- People from Richland, Washington

- Recipients of the Defense Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Defense Superior Service Medal

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the NATO Meritorious Service Medal

- Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Polish Army Medal

- Theranos people

- Trump administration cabinet members

- United States Marine Corps generals

- United States Marine Corps officers

- United States secretaries of defense

- Recipients of the Meritorious Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Humanitarian Service Medal

- Washington (state) independents