James Berry (poet)

James Berry | |

|---|---|

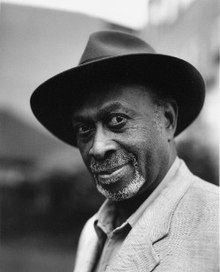

James Berry by Sal Idriss | |

| Born | 28 September 1924 |

| Died | 20 June 2017 (aged 92) |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Notable work | Bluefoot Traveller (1976) News for Babylon (1984) |

| Spouse | Mary Berry |

| Partner | Myra Barrs (1984–his death)[1] |

| Awards | National Poetry Competition |

James Berry, OBE, Hon. FRSL (28 September 1924 – 20 June 2017),[1] was a Jamaican poet who settled in England in the 1940s. His poetry is notable for using a mixture of standard English and Jamaican Patois.[2] Berry's writing often "explores the relationship between black and white communities and in particular, the excitement and tensions in the evolving relationship of the Caribbean immigrants with Britain and British society from the 1940s onwards".[3] As the editor of two seminal anthologies, Bluefoot Traveller (1976) and News for Babylon (1984), he was in the forefront of championing West Indian/British writing.[4]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]The son of Robert Berry, a smallholder, and his wife Maud, a seamstress, James Berry was born in the coastal village of Fair Prospect, growing up in rural Portland, Jamaica, the fourth child in a family of six.[1][5][6] He began writing stories and poems while still at school.[2] During the Second World War, as a teenager, he went to work for six years (1942–48) in the United States, working in New Orleans,[6] before returning to Jamaica.

In his own words:

- "America had run into a shortage of farm labourers and was recruiting workers from Jamaica. I was 18 at the time. My friends and I, all anxious for improvement and change, were snapped up for this war work and we felt this to be a tremendous prospect for us. But we soon realised, as we had been warned, that there was a colour problem in the United States that we were not familiar with in the Caribbean. America was not a free place for black people. When I came back from America, pretty soon the same old desperation of being stuck began to affect me. When the Windrush came along, it was godsend, but I wasn't able to get on the boat.... I had to wait for the second ship to make the journey that year, the SS Orbita."[7]

Career in Great Britain

[edit]Settling in 1948 in Great Britain, Berry attended night school, trained and worked as a telegrapher in London, while also writing.[8] He was reported as saying: "I knew I was right for London and London was right for me. London had books and accessible libraries."[9][10] He later moved to live in Brighton for a period in the late 1970s to the late 1990s.

He became an early member of the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM), founded in 1966 by Edward Kamau Brathwaite, Andrew Salkey and John La Rose,[11][12] and in 1971 was its acting chair.[1] In 1976, Berry compiled the anthology Bluefoot Traveller, featuring the poetry of West Indians in Britain, and the award of a C. Day Lewis Fellowship in 1977 afforded him the opportunity to work full-time on poetry as writer-in-residence at Vauxhall Manor comprehensive school in London.[6] In 1979, Berry's first poetry collection, Fractured Circles, was published by La Rose's New Beacon Books.[1] In 1981, Berry became the first poet of West Indian origin to win the Poetry Society's National Poetry Competition, with his poem "Fantasy of an African Boy"[13][14] – which would become "one of the most anthologised Caribbean poems", as Alastair Niven has noted.[1] Berry edited the landmark anthology News for Babylon: The Chatto Book of Westindian-British Poetry (1984), considered "a ground-breaking publication because its publishing house Chatto & Windus was 'mainstream' and distinguished for its international poetry list".[14]

Berry wrote many books for young readers, including A Thief in the Village and Other Stories (1987), The Girls and Yanga Marshall (1987), The Future-Telling Lady and Other Stories (1991), Anancy-Spiderman (1988), Don't Leave an Elephant to Go and Chase a Bird (1996) and First Palm Trees (1997). His A Story About Afiya, illustrated by Brazilian artist Anna Cunha, was posthumously published by Lantana in 2020 and named one of the New York Times Best Children's Books of the year.[15][16] It was also included in The New York Times list of children's books that "let young minds wonder and wander on their own".[17]

Berry's last book of poetry, A Story I Am In: Selected Poems (2011), draws on five earlier collections: Fractured Circles (1979), Lucy’s Letters and Loving (1982, Chain of Days (1985), Hot Earth Cold Earth (1995) and Windrush Songs (2007).[18] In 1995, his "Song of a Blue Foot Man" was adapted and staged at the Watford Palace Theatre.[4]

In 1990, Berry was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to poetry.[2][19][20] In September 2004, he was one of 50 Black and Asian writers who have made major contributions to contemporary British literature to be featured in the historic "A Great Day in London" photograph at the British Library.[21][22]

In 2007, he was elected an honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[23]

Berry's archives were acquired by the British Library in October 2012.[3][11] Among other items, the archive contains drafts of an unpublished novel, The Domain of Sollo and Sport.[11]

Death and personal life

[edit]Berry died in London on 20 June 2017, aged 92, after suffering from Alzheimer's disease and having lived in care for his last six years.[1][24] He was survived by his son Roger, his daughter Joanna having predeceased him. Mary Berry, who had been his wife, died in 2002.[1] His partner for more than 30 years was Myra Barrs,[1] a specialist in English language and literacy, who died in 2023.[25][26]

Selected publications

[edit]- Bluefoot Traveller: An Anthology of Westindian Poets in Britain (editor), London: Limestone Publications, 1976; revised edition Bluefoot Traveller: Poetry by West Indians in Britain, London: Harrap, 1981

- Fractured Circles (poetry), London: New Beacon Books, 1979

- Lucy's Letters and Loving, London: New Beacon Books, (1982)

- News for Babylon: The Chatto Book of Westindian-British Poetry (editor), London: Chatto & Windus, 1984

- Chain of Days, Oxford University Press, 1985

- A Thief in the Village and other stories (for children), London: Hamish Hamilton, 1987

- The Girls and Yanga Marshall: four stories (for children), London: Longman, 1987

- Anancy-Spiderman: 20 Caribbean Folk Tales (for children), illustrated by Joseph Olubo, London: Walker Books, 1988

- When I Dance (for children), Hamish Hamilton, 1988

- Brighton Festival Poem 1989: Meeting in a Sense of Freedom with Other Poems (1989)

- Isn't My Name Magical? (for children), Longman/BBC, 1990

- The Future-Telling Lady and other stories (for children), London: Hamish Hamilton, 1991

- Ajeemah and his Son (for children), USA: HarperCollins, 1992

- Celebration Song (for children), London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994

- Classic Poems to Read Aloud (editor), London: Kingfisher Books, 1995

- Hot Earth Cold Earth, Bloodaxe Books, 1995

- Playing a Dazzler (for children), London: Hamish Hamilton, 1996

- Don't Leave an Elephant to Go and Chase a Bird (for children), USA: Simon & Schuster, 1996

- Everywhere Faces Everywhere (for children), Simon and Schuster, 1997

- First Palm Trees (for children), illustrated by Greg Couch, Simon & Schuster, 1997

- Around the World in 80 Poems (editor – for children), London: Macmillan, 2001

- A Nest Full of Stars (for children), London: Macmillan, 2002

- Only One of Me (selected poems – for children), London: Macmillan, 2004

- James Berry Reading from his poems for children, CD, The Poetry Archive, 2005

- Windrush Songs, Bloodaxe Books, 2007

- A Story I Am In: Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, 2011

- A Story About Afiya, illustrated by Anna Cunha, Lantana, 2020

Awards

[edit]- 1977–78, C. Day-Lewis Fellowship

- 1981, National Poetry Competition (for "Fantasy of an African Boy")[27]

- 1987, Smarties Prize (for A Thief in the Village)

- 1989, Signal Poetry Award (for When I Dance)

- 1989, Coretta Scott King Book Award

- 1991, Cholmondeley Award

- 1993, Boston Globe-Horn Book Award (for Ajeemah and His Son)

- 2007, Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[28]

Legacy

[edit]The 'James Berry Poetry Prize – "the UK's first poetry prize offering both expert mentoring and book publication for young or emerging poets of colour" – was launched in April 2021, organised by Newcastle Centre for the Literary Arts (NCLA) together with Bloodaxe Books, and supported by funding from Arts Council England.[29][30]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Niven, Alastair (4 July 2017). "James Berry obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ a b c "Channel 4 Learning". Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b Wilcox, Zoe (18 October 2012), "British Library acquires the archive of poet James Berry", Group for Literary Archives & Manuscripts.

- ^ a b National Theatre Black Plays Archive.

- ^ Lowe, Hannah; Myra Barrs (2 January 2015). "James Berry at Ninety". Wasafiri. 30 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1080/02690055.2015.980994. ISSN 0269-0055. S2CID 161628594.

- ^ a b c "James Berry, poet – obituary". The Telegraph. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Ian (19 August 2015), "The Poet James Berry", Black History Month 365.

- ^ Shostak, Elizabeth, "James Berry", Gale Contemporary Black Biography.

- ^ Interview quoted in Onyekachi Wambu, Black British Literature since Windrush, BBC History, 3 March 2011.

- ^ Voices of the Crossing - The impact of Britain on writers from Asia, the Caribbean and Africa. Ferdinand Dennis, Naseem Khan (eds), London: Serpent's Tail, 1998. James Berry: p. 143, "Ancestors I Carry".

- ^ a b c "British Library acquires the archive of Caribbean British poet and writer, James Berry", British Library press release, 16 October 1912.

- ^ "Caribbean Artists Movement", George Padmore Institute Archive Catalogue.

- ^ "National Poetry Competition 1978–1989 | Fantasy of an African Boy". The Poetry Society. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b Dabydeen, David, John Gilmore, Cecily Jones (eds), The Oxford Companion to Black British History, Oxford University Press, 2007, "News for Babylon", p. 343.

- ^ "James Berry's 'A Story about Afiya' makes New York Times list of best Children's books for 2020". Peters Fraser and Dunlop (PFD) Literary Agents. 3 December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ "The 25 Best Children's Books of 2020". The New York Times. 2 December 2020.

- ^ Krauss, Jennifer (4 July 2020). "8 Picture Books That Let Young Minds Wonder and Wander on Their Own". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ James Berry page at Bloodaxe Books Archived 26 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "No. 52173". The London Gazette. 15 June 1990. p. 9.

- ^ "James Berry". Poetry Archive. Retrieved 16 October 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Levy, Andrea (18 September 2004), "Made in Britain. To celebrate the impact of their different perspectives, 50 writers of Caribbean, Asian and African descent gathered to be photographed. Andrea Levy reports on a great day for literature", The Guardian.

- ^ Le Gendre, Kevin (17 October 2004), "Books: A great day for a family get together; Who are the movers and shakers in black British writing? And can they all fit on one staircase?", The Independent on Sunday.

- ^ "James Berry", Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "James Berry 1924-2017", The Poetry Society.

- ^ Rosen, Michael (2 November 2023). "Myra Barrs: A personal memory". UK Literacy Association (UKLA). Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Ellis, Sue (26 November 2023). "Myra Barrs obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "James Berry" Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, British Council, Literature.

- ^ "RSL Fellows | James Berry", The Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Poetry Events | James Berry Poetry Prize Winners' Reading". bloodaxebooks.com. Bloodaxe Books. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "James Berry Poetry Prize winners announced". ncl.ac.uk (Press release). Newcastle University Press Office. 29 October 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

External links

[edit]- British Library announcement of Berry archive acquisition, 16 October 2012

- James Berry at Library of Congress, with 26 library catalog records

- "James Berry" at CLPE – Centre for Literacy in Primary Education.

- 1924 births

- 2017 deaths

- 20th-century Jamaican poets

- 20th-century male writers

- 21st-century Jamaican poets

- 21st-century male writers

- Black British writers

- British anthologists

- British children's writers

- Caribbean Artists Movement people

- Deaths from Alzheimer's disease

- Deaths from dementia in England

- Jamaican emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Jamaican male poets

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire