İznik

İznik | |

|---|---|

District and municipality | |

| |

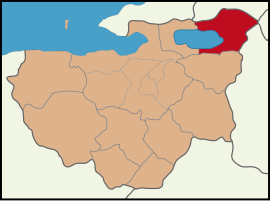

Map showing İznik District in Bursa Province | |

| Coordinates: 40°25′45″N 29°43′16″E / 40.42917°N 29.72111°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Bursa |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kağan Mehmet Usta (AKP) |

Area | 753 km2 (291 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 44,236 |

| • Density | 59/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 16860 |

| Area code | 0224 |

| Website | www |

İznik (Turkish pronunciation: [izˈnik]) is a municipality and district of Bursa Province, Turkey.[2] Its area is 753 km2,[3] and its population 44,236 (2022).[1] The town is at the site of the ancient Greek city of Nicaea, from which the modern name derives. The town lies in a fertile basin at the eastern end of Lake İznik, with ranges of hills to the north and south. As the crow flies, the town is only 90 kilometres (56 miles) southeast of Istanbul but by road it is 200 km (124 miles) around the Gulf of İzmit. It is 80 km (50 miles) by road from Bursa.

İznik has been a district centre of the province of Bursa since 1930 but belonged to the district of Kocaeli between 1923 and 1927. It was a township of Yenişehir district(connected to Bilecik before 1926) between 1927 and 1930.

Ancient Nicaea was ringed with walls that survive to this day, despite having been pierced in places to accommodate roads. Inside the walls stands the Ayasofya Mosque where the Second Council of Nicaea was held in A.D. 787. The town is famous for the Iznik tiles and pottery.

Etymology

[edit]İznik derives from the Ancient Greek name of the city, Νίκαια Nikaia (Latinized as Nicaea), prefixed with εἰς eis, meaning 'to' or 'into'. The Ottoman Turkish spelling is ازنيق: İznîq.[citation needed]

İznik appears as نيقية (Nîkıye) in Arabic sources, while Ibn Battuta, who visited the area, recorded it as يزنيك (Yiznîk).[4]

History

[edit]

In ancient times, this was the site of Nicaea, a Hellenistic city founded by Antigonus in 316 BC.

In 1331, Orhan captured the city from the Byzantines and for a short period the town became the capital of the expanding Ottoman Emirate.[5] The large church of Hagia Sophia in the centre of the town was converted into the Orhan Mosque[6] and a medrese (theological school-Süleyman Paşa Medresesi) and hamam (bathhouse) were built nearby.[7] In 1334 Orhan built another mosque and an imaret (soup kitchen) just outside the Yenisehir gate (Yenişeh Kapısı) on the south side of the town.[8]

The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta stayed in Iznik at the end of 1331 soon after the capture of the town by Orhan.[9] According to Ibn Battuta, the town was in ruins and only inhabited by a small number of people in the service of the sultan. Within the city walls were gardens and cultivated plots with each house surrounded by an orchard. The town produced fruit, walnuts, chestnuts and large sweet grapes.[8][10]

A census in 1520 recorded 379 Muslim and 23 Christian households while another one taken a century later in 1624 recorded 351 Muslim and 10 Christian households. Assuming five members for each household, these figures suggest that the population was around 2,000. Estimates made in the 18th and 19th centuries arrived at similar numbers.[11] The town was poor and the population small even when ceramic production was at its peak during the second half of the 16th century.[12]

The Byzantine city is estimated to have had a population of 20,000–30,000 but in the Ottoman period the town was never prosperous and occupied only a small fraction of the walled area. It was, however, a centre for the production of highly decorated fritware vessels and what are known as İznik tiles during the 16th and 17th centuries.

In 1677 the English clergyman John Covel visited Iznik and found only a third of the town occupied.[13] In 1745 the English traveller Richard Pococke reported that Iznik was no more than a village.[14] A succession of visitors described the town in unflattering terms. For example in 1779, the Italian archaeologist Domenico Sestini wrote that Iznik was nothing but an abandoned town with no life, no noise and no movement.[8][15] In 1797 James Dallaway described Iznik as "a wretched village of long lanes and mud walls...".[8][16]

The town was seriously damaged by the Greek Army in 1921 during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922); the population became refugees and many historical buildings and mosques were damaged or destroyed.[17]

Pottery and tiles

[edit]

Iznik's main period of importance came in the 16th century with the development of a pottery and tile making industry. Iznik ceramic tiles (Turkish: İznik Çini.) were used to decorate many of the mosques designed by Mimar Sinan in Istanbul. However, the ceramics industry declined in the 17th century[18] and İznik was reduced to a minor agricultural settlement when it was bypassed by the railway in the 19th century.

Main sights

[edit]A number of monuments were erected by the early Ottomans in the period between the conquest in 1331 and 1402 when the town was sacked by Timur. Among those that have survived are:

- İznik was originally ringed with 5 km (3 mi) of walls that were about 10 m (33 ft) high and enclosed within a double ditch on the landward sides. The walls incorporated over 100 towers. Large gates on the three landward sides of the walls provided the only entrances to the city. The western part of the walls rose up beside the lake which is sufficiently large that it cannot easily be blockaded from the land. Today the walls are ruined but enough still survives to provide a pleasant walking route.[19]

- Yeşil Mosque (Green Mosque), built for Çandarlı Kara Halil Hayreddin Pasha, the first Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire between 1378 and 1391. It is located near the Lefke Gate on the east side of the town. Damaged in 1922 during the Greco-Turkish War, it was restored between 1956 and 1969.[8][20]

- Hagia Sophia, also known as Aya Sofya,[21] (Greek: Ἁγία Σοφία, "'Holy Wisdom') is a Byzantine-era former church which was built by Justinian I in the middle of the city in the 6th century.[22] It was here that the Second Council of Nicaea, a gathering of Christian bishops, was held in AD 787. After controversial rebuilding, it is now the Ayasofya Mosque (Turkish: Ayasofya Cami).[23]

- Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333). This mosque was built only three years after the Ottoman conquest. The portico on the west side of the building was demolished in 1940 to widen the road.[24]

- Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen (Nilüfer Hatun Imareti) Built in 1388, the building was abandoned for many years but was restored in 1955 and is now a museum.[25]

- Süleyman Pasha Madrasa (mid-14th century). This is one of two surviving medreses in the town. It was restored in the 19th century and again in 1968.[26]

- Mausoleum of Çandarlı Hayreddin Pasha (14th century). The main chamber contains fifteen sarcophagi. A lower room contains three more sarcophagi including that of Ottoman-Tunisian statesman Hayreddin Pasha. It is located in a cemetery outside the Lefke gate to the east of the town.[27]

- Kilns Slight traces remain of the kilns used to make the pottery and tiles that once made İznik famous.

Several monuments survived into the 20th century but were destroyed during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). These include:

- Church of the Koimesis/Dormition (6th–8th century but rebuilt after the 1065 earthquake). The only church in the town that was not transformed into a mosque,[28] it was decorated with 11th-century Byzantine mosaics which survive only in photographs.[29][30]

- Eşrefzâde Rumi Mosque (15th century). Eşrefzâde Rumi was married to the daughter of Hacı Bayram-ı Veli. He founded a sufi sect and after his death in 1469–70 his tomb became a pilgrimage site.[8] The mosque has been restored and the tomb is decorated with Iznik tiles.[31]

- Seyh Kutbeddin Mosque and Mausoleum (15th century). The mosque and mausoleum have been rebuilt.[32][33]

Composition

[edit]There are 46 neighbourhoods in İznik District:[34]

- Aydınlar

- Bayındır

- Beyler

- Boyalıca

- Çakırca

- Çamdibi

- Çamoluk

- Çampınar

- Çandarlı

- Çiçekli

- Derbent

- Dereköy

- Dırazali

- Elbeyli

- Elmalı

- Eşrefzade

- Göllüce

- Gürmüzlü

- Hacıosman

- Hisardere

- Hocaköy

- İhsaniye

- İnikli

- Karatekin

- Kaynarca

- Kırıntı

- Kutluca

- Mahmudiye

- Mahmut Çelebi

- Mecidiye

- Müşküle

- Mustafa Kemal Paşa

- Mustafalı

- Ömerli

- Orhaniye

- Osmaniye

- Sansarak

- Sarıağıl

- Selçuk

- Şerefiye

- Süleymaniye

- Tacir

- Yeni

- Yenişerefiye

- Yeşilcami

- Yürükler

Sport

[edit]The İznik Ultramarathon is a 130 km (81 mi) endurance running event that has taken place around Lake İznik every April since 2012. It is the country's longest single-stage athletics competition.[35]

International relations

[edit] Jingdezhen, China

Jingdezhen, China Khulo, Georgia

Khulo, Georgia Nikaia, Greece

Nikaia, Greece Pithiviers, France

Pithiviers, France Spandau (Berlin), Germany

Spandau (Berlin), Germany Talas, Kyrgyzstan

Talas, Kyrgyzstan Tutin, Serbia

Tutin, Serbia

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Büyükşehir İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Semavi Eyice (1988–2016). "İznik". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ Raby 1989, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Tsivikis, Nikolaos (23 March 2007), "Nicaea, Church of Hagia Sophia", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ St. Sophia Museum, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ a b c d e f Raby 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Dunn 2005, p. 158 note 20. Raby (1989, p. 20) suggests a date between 1334 and 1339.

- ^ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, pp. 323–324; Gibb 1962, p. 453

- ^ Raby 1989, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Raby 1989, p. 21.

- ^ Covel 1893, p. 281.

- ^ Pococke 1745, p. 123.

- ^ Sestini 1789, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Dallaway 1797, p. 169.

- ^ Uyan, Ayhan (28 November 2011), İznik'te Milli Mücadelede Yunan Tahribatı, iznikrehber.com, retrieved 19 June 2013

- ^ "Iznik and Ottoman ceramics". Mini-site.louvre.fr. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ "Walls of Nicaea". The Byzantine Legacy. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Green Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ "İznikte Gezilecek Yerler". Türkiye'nin En Güncel Gezi ve Seyahat Sitesi, GeziPedia.net (in Turkish). Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Hazlitt, Classical Gazetteer, "Nicæa"

- ^ "Ayasofya Orhan Camiisindeki restorasyon sorunları ufak tefekmiş! haberi". Arkeolojik Haber. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Haci Özbek Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Süleyman Pasa Madrasa, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Tomb of Çandarli Hayreddin Pasa, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Kastrinakis, Nikos (16 June 2005), "Nicaea (Byzantium), Dormition Church", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Mango 1959.

- ^ Kanaki, Elena (22 June 2005), "Nicaea (Byzantium), Church of the Dormition, Mosaics", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Esrefzade Rumi Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ Seyh Kutbeddin Mosque and Tomb, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014

- ^ "Şeyh Kutbettin Camii ve Türbesi / Osmanlı mimarisi".

- ^ Mahalle, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "İznik'te maraton heyecanı başladı". Sabah (in Turkish). 14 April 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Kardeş Şehirler". iznik.bel.tr (in Turkish). İznik. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Covel, John (1893). "Extracts from the diaries of John Covel (1670–1679)". In Bent, J. Theodore (ed.). Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant. London: Hakluyt Society.

- Dallaway, James (1797). Constantinople Ancient and Modern: with excursions to the shores and islands of the archipelago and to the Troad. London: T. Cadell, junr. & W. Davies.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R., eds. (1854). Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah, Volume 2 (in Arabic and French). Paris: Société Asiatic.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24385-4. First published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Gibb, H.A.R., ed. (1962). The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 2). London: Hakluyt Society.

- Mango, Cyril (1959). "The date of the narthex mosaics of the Church of the Dormition at Nicaea". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 13: 245–252. doi:10.2307/1291137. JSTOR 1291137.

- Pococke, Richard (1745). A Description of the East and Some Other Countries. Vol. 2 part 2. London: self published.

- Raby, Julian (1989). "İznik, 'Une village au milieu des jardins'". In Petsopoulos, Yanni (ed.). Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. London: Alexandra Press. pp. 19–22. ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.

- Sestini, Domenico (1789). Voyage dans la Grèce asiatique, à la péninsule de Cyzique, à Brusse et à Nicée: avec des détails sur l'histoire naturelle de ces contrées (in French). London and Paris: Leroy.

Further reading

[edit]- Alioğlu, E. Fusun (2001). "Similarities between early Ottoman architecture and local architecture or Byzantine architecture in Iznik". ICOMOS International Millennium Congress. More than two thousand years in the history of architecture, Session 2, Historic Towns (PDF). UNESCO-ICOMOS.

- Alioğlu, E.Fusun (2001). "Establishing the sustainable identity of a historical city field of research: Iznik". ICOMOS International Millennium Congress. More than two thousand years in the history of architecture, Session 2, Historic Towns (PDF). UNESCO-ICOMOS.

- Raby, Julian (1976). "A seventeenth century description of İznik-Nicaea". Istanbuler Mitteilungen. 26: 149–188.

External links

[edit] Iznik travel guide from Wikivoyage

Iznik travel guide from Wikivoyage- Iznik, ArchNet. Information on the historic buildings in the town.

- 300+ photographs of the town and sights