Name of Iran

Historically, Iran was commonly referred to as "Persia" in the Western world.[1] Likewise, the modern-day ethnonym "Persian" was typically used as a demonym for all Iranian nationals, regardless of whether or not they were ethnic Persians. This terminology prevailed until 1935, when, during an international gathering for Nowruz, the Iranian king Reza Shah Pahlavi officially requested that foreign delegates begin using the endonym "Iran" in formal correspondence. Subsequently, "Iran" and "Iranian" were standardized as the terms referring to the country and its citizens, respectively. Later, in 1959, Pahlavi's son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi announced that it was appropriate to use both "Persia" and "Iran" in formal correspondence.[2] However, the issue is still debated among Iranians.[3] A variety of scholars from the Middle Ages, such as the Persian polymath Al-Biruni, also used terms like "Xuniras" (Avestan: Xvaniraθa-, transl. "self-made, not resting on anything else") to refer to Iran: "which is the center of the world, [...] and it is the one wherein we are, and the kings called it the Iranian realm."[4]

Etymology of Iran

[edit]The Modern Persian word Īrān (ایران) derives immediately from Middle Persian Ērān (Pahlavi spelling: ʼyrʼn), attested in a third century AD inscription that accompanies the investiture relief of the first Sassanid king Ardashir I at Naqsh-e Rustam.[5] In this inscription, the king's Middle Persian appellation is ardašīr šāhān šāh ērān in the Parthian language inscription that accompanies the Middle Persian one. The king is also titled ardašīr šāhān šāh aryān (Pahlavi: ... ʼryʼn) both meaning king of kings of the Aryans. [5] [6]

The gentilic ēr- and ary- in ērān and aryān derives from Old Iranian *arya-[5] ([Old Persian] airya-, Avestan airiia-, etc.), meaning "Aryan",[5] in the sense of "of the Iranians".[5][7] This term is attested as an ethnic designator in Achaemenid inscriptions and in Zoroastrianism's Avesta tradition,[8][n 1] and it seems "very likely"[5] that in Ardashir's inscription ērān still retained this meaning, denoting the people rather than the empire.

The name "Iran" is first attested in the Avesta as airyānąm (the text of which is composed in Avestan, an old Iranian language spoken in the northeastern part of Greater Iran, or in what are now Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan).[9][10][11][12]

It reappears in the Achaemenid period where the Elamite version of the Behistun Inscription twice mentions Ahura Mazda as nap harriyanam "the god of the Iranians".[13][14]

Notwithstanding this inscriptional use of ērān to refer to the Iranian peoples, the use of ērān to refer to the empire (and the antonymic anērān to refer to the Roman territories) is also attested by the early Sassanid period. Both ērān and anērān appear in 3rd century calendrical text written by Mani. In an inscription of Ardashir's son and immediate successor, Shapur I "apparently includes in Ērān regions such as Armenia and the Caucasus which were not inhabited predominantly by Iranians".[15] In Kartir's inscriptions (written thirty years after Shapur's), the high priest includes the same regions (together with Georgia, Albania, Syria and the Pontus) in his list of provinces of the antonymic Anērān.[15] Ērān also features in the names of the towns founded by Sassanid dynasts, for instance in Ērān-xwarrah-šābuhr "Glory of Ērān (of) Shapur". It also appears in the titles of government officers, such as in Ērān-āmārgar "Accountant-General (of) Ērān" or Ērān-dibirbed "Chief Scribe (of) Ērān".[5]

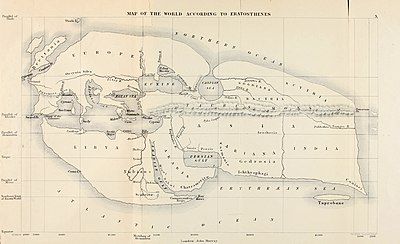

The term Iranian appears in ancient texts with diverse variations. This includes Arioi (Herodotus), Arianē (Eratosthenes apud Strabo), áreion (Eudemus of Rhodes apud Damascius), Arianoi (Diodorus Siculus) in Greek and Ari in Armenian; those, in turn, come from the Iranian forms: ariya in Old Persian, airya in Avestan, ariao in Bactrian, ary in Parthian and ēr in Middle Persian.[16]

Etymology of Persia

[edit]

The Greeks (who had previously tended to use names related to "Median") began to use adjectives such as Pérsēs (Πέρσης), Persikḗ (Περσική) or Persís (Περσίς) in the fifth century BC to refer to Cyrus the Great's empire (a word understood to mean "country").[17] Such words were taken from the Old Persian Pārsa – the name of the people from whom Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty emerged and over whom he first ruled (before he inherited or conquered other Iranian Kingdoms). The Pars tribe gave its name to the region where they lived (the modern day province is called Fars/Pars), but the province in ancient times was smaller than its current area.[citation needed] In Latin, the name for the whole empire was Persia, while the Iranians knew it as Iran or Iranshahr.[citation needed]

In the later parts of the Bible, where this kingdom is frequently mentioned (Books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah), it is called Paras (Biblical Hebrew: פרס), or sometimes Paras u Madai (פרס ומדי), ("Persia and Media"). The Arabs likewise referred to Iran and the Persian (Sassanian) Empire as Bilād Fāris (Arabic: بلاد فارس), in other words "Lands of Persia", which would become the popular name for the region in Muslim literature. They also used Bilād Ajam (Arabic: بلاد عجم) as an equivalent or synonym to "Persia". The Turks also used this term, but adapted to Iranian (specifically, Persian) language form as "Bilad (Belaad) e Ajam".

A Greek folk etymology connected the name to Perseus, a legendary character in Greek mythology. Herodotus recounts this story,[18] devising a foreign son, Perses, from whom the Persians took the name. Apparently, the Persians themselves knew the story,[19] as Xerxes I tried to use it to suborn the Argives during his invasion of Greece, but ultimately failed to do so.

Xuniras

[edit]In the Iranian tradition, the world is divided into seven circular regions, or karshvars, separated from one another by forests, mountains, or water. Six of those regions flank a central one called Xvaniraθa- in Avesta and Xuniras in New Persian, which probably means ‘self-made, not resting on anything else’. It was equal in size to all the rest combined and surpassed them in prosperity and fortune. Originally, only Xuniras was inhabited by humans, which also hosted the "Iranian home" (Airyō.šayana- in the Avestan). But in the later tradition, that is, from about 620, Xuniras came to be the same as Iran itself, with known countries such as the Roman Empire and China surrounding it. The Abu-Mansuri Shahnameh describes Xuniras as such: "(and) the seventh, which is the center of the world, Xuniras-e bāmi (splendid Xuniras), and it is the one wherein we are, and the kings called it the Iranian realm/Ērānšahr." Another scheme of the seven regions of the world is reported by Abu Rayhan Biruni, who similarly arranges known nations into six connectedcircles surrounding the central Ērānšahr.[4]

Name in the Western world

[edit]The exonym Persia was the official name of Iran in the Western world before March 1935, but the Iranian peoples inside their country since the time of Zoroaster (probably circa 1000 BC), or even before, have called their country Arya, Iran, Iranshahr, Iranzamin (Land of Iran), Aryānām (the equivalent of Iran in the proto-Iranian language) or its equivalents. The term Arya has been used by the Iranian people, as well as by the rulers and emperors of Iran, from the time of the Avesta. Evidently from the time of the Sassanids (226–651 CE) Iranians have called it Iran, meaning the "Land of the Aryans" and Iranshahr. In Middle Persian sources, the name Arya and Iran is used for the pre-Sassanid Iranian empires as well as the Sassanid empire. As an example, the use of the name "Iran" for Achaemenids in the Middle Persian book of Arda Viraf refers to the invasion of Iran by Alexander the Great in 330 BC.[20] The Proto-Iranian term for Iran is reconstructed as *Aryānām (the genitive plural of the word *Arya); the Avestan equivalent is Airyanem (as in Airyanem Vaejah). The internal preference for "Iran" was noted in some Western reference books (e.g. the Harmsworth Encyclopaedia, circa 1907, entry for Iran: "The name is now the official designation of Persia.") but for international purposes, Persia was the norm.

In the mid 1930s, the ruler of the country, Reza Shah Pahlavi, moved towards formalising the name Iran instead of Persia for all purposes. In the British House of Commons the move was reported upon by the United Kingdom Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs as follows:[21]

On the 25th December [1934] the Persian Ministry for Foreign Affairs addressed a circular memorandum to the Foreign Diplomatic Missions in Tehran requesting that the terms "Iran" and "Iranian" might be used in official correspondence and conversation as from the next 21st March, instead of the words "Persia" and "Persian" hitherto in current use. His Majesty's Minister in Tehran has been instructed to accede to this request.

The decree of Reza Shah Pahlavi affecting nomenclature duly took effect on 21 March 1935.

To avoid confusion between the two neighboring countries of Iran and Iraq, which were both involved in WWII and occupied by the Allies, Winston Churchill requested from the Iranian government during the Tehran Conference for the old and distinct name "Persia to be used by the United Nations [i.e., the Allies] for the duration of the common War". His request was approved immediately by the Iranian Foreign Ministry. The Americans, however, continued using Iran as they then had little involvement in Iraq to cause any such confusion.

In the summer of 1959, following concerns that the native name had, as Mohammad Ali Foroughi[22] put it, "turned a known into an unknown", a committee was formed, led by noted scholar Ehsan Yarshater, to consider the issue again. They recommended a reversal of the 1935 decision, and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi approved this. However, the implementation of the proposal was weak, simply allowing Persia and Iran to be used interchangeably.[2] Today, both terms are common; Persia mostly in historical and cultural contexts, "Iran" mostly in political contexts.

In recent years most exhibitions of Persian history, culture and art in the world have used the exonym Persia (e.g., "Forgotten Empire; Ancient Persia", British Museum; "7000 Years of Persian Art", Vienna, Berlin; and "Persia; Thirty Centuries of Culture and Art", Amsterdam).[23] In 2006, the largest collection of historical maps of Iran, entitled Historical Maps of Persia, was published in the Netherlands.[24]

Modern debate in Iran

[edit]In the 1980s, Professor Ehsan Yarshater (editor of the Encyclopædia Iranica) started to publish articles on this matter (in both English and Persian) in Rahavard Quarterly, Pars Monthly, Iranian Studies Journal, etc. After him, a few Iranian scholars and researchers such as Prof. Kazem Abhary, and Prof. Jalal Matini followed the issue. Several times since then, Iranian magazines and websites have published articles from those who agree or disagree with usage of Persia and Persian in English.

There are many Iranians in the West who prefer Persia and Persian as the English names for the country and nationality, similar to the usage of La Perse/persan in French.[25] According to Hooman Majd, the popularity of the term Persia among the Iranian diaspora stems from the fact that "'Persia' connotes a glorious past they would like to be identified with, while 'Iran' since 1979 revolution… says nothing to the world but Islamic fundamentalism."[3]

Official names of Iranian states

[edit]Since 1 April 1979, the official name of the Iranian state is Jomhuri-ye Eslâmi-ye Irân (Persian: جمهوری اسلامی ایران), which is generally translated as the Islamic Republic of Iran in English.

Other official names were Dowlat-e Aliyye-ye Irân (Persian: دولت علیّهٔ ایران) meaning the Sublime State of Persia and Kešvar-e Šâhanšâhi-ye Irân (Persian: کشور شاهنشاهی ایران) meaning Imperial State of Persia and the Imperial State of Iran after 1935.

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- The History of the Idea of Iran, A. Shapur Shahbazi in Birth of the Persian Empire by V. S. Curtis and S. Stewart, 2005, ISBN 1-84511-062-5

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the Avesta the airiia- are members of the ethnic group of the Avesta-reciters themselves, in contradistinction to the anairiia-, the "non-Aryas". The word also appears four times in Old Persian: One is in the Behistun inscription, where ariya- is the name of a language or script (DB 4.89). The other three instances occur in Darius I's inscription at Naqsh-e Rustam (DNa 14-15), in Darius I's inscription at Susa (DSe 13-14), and in the inscription of Xerxes I at Persepolis (XPh 12-13). In these, the two Achaemenid dynasts describe themselves as pārsa pārsahyā puça ariya ariyaciça "a Persian, son of a Persian, an Ariya, of Ariya origin". "The phrase with ciça, "origin, descendance", assures that it [i.e. ariya] is an ethnic name wider in meaning than pārsa and not a simple adjectival epithet."[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Fishman, Joshua A. (2010). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: Disciplinary and Regional Perspectives. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0195374926.

'Iran' and 'Persia' are synonymous. The former has always been used by the Iranian speaking peoples themselves, while the latter has served as the international name of the country in various languages

. - ^ a b Yarshater, Ehsan (1989). "Communication". Iranian Studies. XXII (1): 62–65. doi:10.1080/00210868908701726. JSTOR 4310640. Reprinted online as "Persia or Iran, Persian or Farsi" (Archived 2010-10-24 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ a b Majd, Hooman, The Ayatollah Begs to Differ: The Paradox of Modern Iran, by Hooman Majd, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 23 September 2008, ISBN 0385528426, 9780385528429. p. 161

- ^ a b Shahbazi, A. Shapur. "HAFT KEŠVAR -- Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g MacKenzie, David Niel (1998). "Ērān, Ērānšahr". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 8. Costa Mesa: Mazda. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger (1987). "Aryans". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 684–687. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ a b Bailey, Harold Walter (1987). "Arya". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 681–683. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ William W. Malandra (20 July 2005). "ZOROASTRIANISM i. HISTORICAL REVIEW". Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Nicholas Sims-Williams. "EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES". Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "IRAN". Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ K. Hoffmann. "AVESTAN LANGUAGE I-III". Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Pierre., Briant (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander : a history of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7. OCLC 733090738.

- ^ Hutter, Manfred (12 December 2015). "Probleme iranischer Literatur und Religion unter den Achämeniden". Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 127 (4): 547–564. doi:10.1515/zaw-2015-0034. ISSN 1613-0103. S2CID 171378786.

- ^ a b Gignoux, Phillipe (1987). "Anērān". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 30–31. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 13 April 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1882). Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott (eds.). Lexicon of the Greek Language. Oxford. p. 1205.

- ^ Herodotus. "61". Histories. Vol. Book 7.

- ^ Herodotus. "150". Histories. Vol. Book 7.

- ^ Arda Viraf Archived 14 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine (1:4; 1:5; 1:9; 1:10; 1:12; etc.)

- ^ HC Deb 20 February 1935 vol 298 cc350-1 351

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (1989). "Communication". Iranian Studies. 22 (1): 62–65. doi:10.1080/00210868908701726. JSTOR 4310640.

- ^ Hermitage (20 September 2007). ""Persia", Hermitage Amsterdam". Hermitage. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

Persian objects at Hermitage

- ^ Brill (20 September 2006). "General Maps of Persia 1477 - 1925". Brill website. Brill. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2006.

Iran, or Persia as it was known in the West for most of its long history, has been mapped extensively for centuries but the absence of a good cartobibliography has often deterred scholars of its history and geography from making use of the many detailed maps that were produced. This is now available, prepared by Cyrus Alai who embarked on a lengthy investigation into the old maps of Persia, and visited major map collections and libraries in many countries ...

- ^ Evason, Nina (1 January 2016). "Iranian Culture: Other Considerations". Cultural Atlas. Special Broadcasting Service.

External links

[edit]- The names of Iran in the course of history at hamshahrionline.ir

- Iran and Persia- Are they the same? at heritageinstitute.com