Ålvik

Ålvik | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Ålvik | |

| Coordinates: 60°25′57″N 06°25′54″E / 60.43250°N 6.43167°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| Region | Western Norway |

| County | Vestland |

| District | Hardanger |

| Municipality | Kvam |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.70 km2 (0.27 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 37 m (121 ft) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

• Total | 487 |

| • Density | 696/km2 (1,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Post Code | 5614 Ålvik |

Ålvik is a village in the municipality of Kvam in Vestland county, Norway. The village "urban area" consists of the settlements of Ytre Ålvik og Indre Ålvik (outer and inner Ålvik) and Vikadal. The settlements are located on either side of a ridge with Vikadal in between. Indre Ålvik has been heavily industrialised since the early 1900s, when Bjølvefossen A/S was established.[3] The village lies along the Ålvik bay on the northern shore of the Hardangerfjord.[4] Ålvik Church is located in the village.

The 0.7-square-kilometre (170-acre) village has a population (2019) of 487 and a population density of 696 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,800/sq mi).[1]

History

[edit]The name "Ålvik" is probably derived from Old Norse word ǫlr which means "alder" and the word vik which means "bay".[5] The settlement here dates back at least to 600-700 BC, as documented by bronze artifacts found in the Vikedal area.[6][7] In medieval times, Ålvik belonged to the estates of Norheim in Norheimsund.[8]

The foundations for Indre Ålvik as an industrial district were laid in 1905, when Bjølvefossen A/S was incorporated to exploit the Bjølvo waterfalls for hydroelectric energy.[9] In 1907, the village still had only 74 inhabitants, as little activity took place until Bjølvefossen A/S was sold to Elektrokemisk A/S in 1913. After this, construction of the Bjølvefossen hydroelectric plant commenced. The construction was however stalled due to concession disputes, as it was claimed that the work on the plant had begun before Norwegian escheat laws had been put in force in 1907.

The disputes were solved in 1916 and both the plant and factories were completed by 1919, producing calcium carbide for a brief time. The village's population briefly rose by 500 workers, but most left shortly thereafter, as financial problems and an accident destroying the pipelines that supplied water from the hydroelectric reservoir brought production to a halt. This forced Bjølvefossen A/S to default on large loans.[10] Large-scale production was only resumed in 1928, when, after the pledgees had established contact with C. Tennant's Sons & Co., Bjølvefossen A/S was given major sales contracts for ferrosilicon to the British steel industry, in an effort to open a price war with the European ferrosilicon syndicate.[11] Production was briefly hit by the Great Depression, but quickly rebounded and a production line for ferrochrome was established in 1934, the same year that the company saw its first profit.[12]

Ålvik gained a road connection to Bergen in 1937, when the Fyksesund Bridge was opened.[13] Nearly all of the village's infrastructure was owned by Bjølvefossen A/S for a long time, to a great extent making it a company town, and it was a separate regulatory area until 1965.[14]

In the 1950s several new furnaces for production of ferrochrome and ferrosilicon were installed.[15] During the 1960s, Bjølvefossen struggled to remain competitive, yet was able to invest in new production facilities on both production lines. In the 1970s, however, new technology in steel production reduced demand for the low-carbon ferrochrome that was produced. Government environmental regulations also put pressure on the production economy. Employment at the plant thus peaked at about 600 in this decade,[16] before ferrochrome production was discontinued on the old production line in 1979 and on the new in 1983.[17] Ferrosilicon production was prioritised to comply with environmental standards, furnaces were rebuilt to a closed type, making it possible to recycle excess heat in a steam turbine and to remove all dust from the discharge fumes. The dust, silica slurry, was found to be a saleable product.[18]

The 1970s saw the entrance of women into production positions at the plant. Before this, the female population of Ålvik was mostly engaged in housekeeping, although some positions were open to women in cleaning and clerk jobs, besides public services. The first women begun work in the packing facilities, and relatively few took positions at the furnaces.[19]

In 2001, the owner, Elkem decided to lay off 100 of 245 workers at Bjølvefossen A/S.[20]

Natural geography

[edit]Ålvik is situated on the northern side of the Hardangerfjord, facing the deepest stretch of the fjord.[21] Ålvik is divided by a ridge into two main settlements, Indre Ålvik and Ytre Ålvik. The name Ålvik denotes the two settlements as a unit.[22]

The bedrock in the Ålvik area consists mainly of gabbro and granite from the Bergsdal field.[23] The vegetation at sea level is sarmatic mixed forest, rich in alm. Mountainous forests are found at higher altitudes.[24] The village has several populations of the orchid sword-leaved helleborine[22] and a natural reserve containing an especially large population of taxus baccata.[25]

Economy

[edit]The former Bjølvefossen A/S is the village's main employer, it has historically dominated to such an extent that the village has been referred to as the most typical monotown in Norway.[3] It is now a subsidiary of Elkem, Elkem Bjølvefossen, which in turn is owned by China National Bluestar.[26] In 2006 it was decided to move ferrosilicon production to Elkem Iceland, and at that time the plant had a staff of about 160.[27] Elkem has since announced that the old production will be replaced by a process recycling waste from aluminium production, which will require a staff of about 60.[28] However, as of March 2012, production was still running at full capacity, and hiring new staff was being discussed.[29]

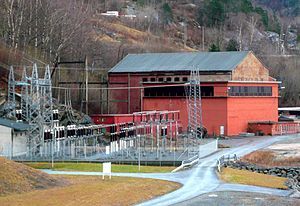

Bjølvo kraftverk, the hydroelectric plant originally built to power industrial production was returned to state ownership by escheat in 1964, and is now owned by Statkraft. The current, modernised plant, Nye Bjølvo, was completed in 2006 and at that time had the highest free-fall pressure shaft of any European hydroelectric plant, at more than 600 m. It has a yearly output of about 390 GWh.[30] The plant exploits the reservoir Bjølsegrøvatnet, which has a regulated surface at 850–879 meters above sea level.[31]

The municipality of Kvam runs the following public services in Ålvik: a kindergarten, a school covering the 1st through 7th grades, a medical office and a care home.[22]

Cultural life and heritage

[edit]The Ålvik Industrial Worker's Museum documents the village's labour heritage through the exposition of two restored worker's apartments typical to the 1920s and 50s, and is housed in an original neo-classical building.[32][33] In a cooperation between Elkem Bjølvefossen and Kvam municipality, an artist's collective was established in one of Bjølvefossen's buildings. This arrangement has now expired, and its future is unclear.[34] In a project developed in cooperation with the Bergen Academy of Art and Design, a co-localised café and library was established in 2010.[35] The village has a wealth of volunteer organisations, among them Ålvik Rock, which stages a Rock Festival each September.[36]

After the completion of Nye Bjølvo hydroelectric plant, the old funicular became obsolete. It was originally built for construction and maintenance access to the original pipes leading water from the hydroelectric reservoir to the plant, and had a maximal inclination of 61 degrees along its 1500-meter course. It was discussed whether it could be conserved as part of the region's cultural heritage and run as a tourist attraction, but this proposal failed.[37][38]

References

[edit]- Fossåskaret, Erik; Storås, Frode, eds. (1999). Ferrofolket ved fjorden. Globale tema i lokal soge - Bjølvefossen, Ålvik, Hardanger [The Ferro-people by the Fjord. Global Themes in Local History - Bjølvefossen, Ålvik, Hardanger] (in Norwegian). Bergen. ISBN 82-7326-057-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brekke, Nils Georg, ed. (1993). Kulturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland [Itinerary of Cultural History - Hordaland] (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland county / Nord 4 Vestkyst. ISBN 82-7326-026-7.

- Helland-Hansen, William, ed. (2004). Naturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland [Itinerary of Natural History - Hordaland] (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland county / Nord 4 Bokverksted. ISBN 978-82-7326-061-1.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Statistisk sentralbyrå (1 January 2019). "Urban settlements. Population and area, by municipality".

- ^ "Ålvik, Kvam (Hordaland)" (in Norwegian). yr.no. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ a b 'Nytt fellesskap i ny type samfunn' in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p46.

- ^ "Indre Ålvik". Store Norske Leksikon (online version) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Brekke (ed.), side 368.

- ^ Brekke (ed.), p369.

- ^ "Bronsefunn frå Ålvik". digitaltfortalt.no. Norsk kulturråd. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Brekke (ed.),p371.

- ^ Martin Byrkjeland:'Spelet om Bjølvefossen' [The game about Bjølvefossen] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), pp18-19.

- ^ Martin Byrkjeland:'Spelet om Bjølvefossen' [The game about Bjølvefossen] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), pp27-32.

- ^ Martin Byrkjeland:'Spelet om Bjølvefossen' [The game about Bjølvefossen] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), pp36-40.

- ^ Martin Byrkjeland:'Spelet om Bjølvefossen' [The game about Bjølvefossen] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p40.

- ^ Brekke (ed.), p88.

- ^ 'Her på stedet' [In this place] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p152.

- ^ Jørund Falnes:'De lunefulle ovnene' [The capricious furnaces] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p94.

- ^ Eva-Marie Tveit:'Et mykere verk' [A softer plant] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p127.

- ^ Jørund Falnes:'De lunefulle ovnene' [The capricious furnaces] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p94-95.

- ^ Jørund Falnes:'De lunefulle ovnene' [The capricious furnaces] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p96.

- ^ Eva-Marie Tveit:'Et mykere verk' [A softer plant] in (Fossåskaret and Storås), p124-25.

- ^ "Nedlagt tross overskudd" [Discontinued despite profits]. Brennpunkt (in Norwegian). Norsk Rikskringkasting. 11 December 2001. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Helland-Hansen (ed.), p64

- ^ a b c Frank Tangen. "Ålvik". Municipality web page. Kvam municipality. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Helland-Hansen (ed.), pp2-3

- ^ Helland-Hansen (ed.), pp140 and 570-571

- ^ "FOR 2000-10-13 nr 1023: Forskrift om freding av Barlindflaten som naturreservat, Kvam kommune, Hordaland" [Decree on the protection of Barlindflaten as a natural reserve, Kvam municipality, Hordaland]. Lovdata (in Norwegian). Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Christian Lura (11 January 2011). "Orkla selger Elkem for 12 milliarder" [Orkla sells Elkem for 12 billion NOK] (in Norwegian). Bergens Tidende. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Jakobsen, Stig-Erik; Stavø Høvig, Øystein; Slinning, Alf-Emil. "Sluttevaluering av omstillingsarbeidet i Ålvik vekst Kvam KF" [Final evaluation of the restructuring projects of Ålvik Growth municipal company] (PDF). Bergen University College Journal, no 5, 2011 (in Norwegian). Høgskolen i Bergen. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Jannicke Nilsen (14 November 2007). "Elkems miljøprosjekt slipper kvotekrav" [Elkem's environmental project exempt from emission quotas] (in Norwegian). Teknisk ukeblad. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Elkem Bjølvefossen for full maskin" [Elkem Bjølvefossen running at full capacity] (in Norwegian). Hordaland Folkeblad. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Knut Strøm (3 December 2002). "Rekord i trykksjakt" [Record-breaking pressure shaft] (in Norwegian). Teknisk Ukeblad. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Bjølvo reguleringsområde" [Bjølvo regulation plan] (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ (Fossåskaret and Storås)

- ^ "Ålvik Industriarbeidermuseum" [Ålvik Industrial Worker's Museum]. Official tourist information (in Norwegian). Kvam municipality. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Kunstnarhus til sals" [Artist's house for sale] (in Norwegian). Hordaland Folkeblad. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Stipendiat Linda Lien med unikt kaféprosjekt i Ålvik sentrum" [PhD student Linda Lien presents unique café project in central Ålvik]. Official web page (in Norwegian). Bergen Academy of Art and Design. 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Festivalar" [Festivals]. Official tourist information (in Norwegian). Kvam municipality. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Randi Storaas (7 April 2009). "Eit annleis Hardanger" [A different Hardanger] (in Norwegian). Bergens Tidende. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Svendsen, Roy Hilmar; Løland, Leif Rune (2 May 2009). "Stopper "Fløybane" i Hardanger" [No funicular in Hardanger] (in Norwegian). Norsk Rikskringkasting. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

External links

[edit]- Ålvik.info - Volunteer-driven information page for and about Ålvik (Wayback Machine)

- Alvikrock.no - Ålvik Rock's official web page

- Trallebanen, Ålvik i Hardanger (Funicular, Ålvik, Hardanger) on YouTube