Indium Corporation

| |

| Industry | Electronics, Semiconductor, Solar, Thin-film, and Thermal management |

|---|---|

| Founded | March 13, 1934 in Clinton, New York, United States |

| Founders | William S. Murray, J. Robert Dyer Jr., Daniel Gray |

| Fate | Active |

| Headquarters | , |

Key people | Greg Evans (CEO)[1] |

| Products | indium, Compounds |

| Website | www |

Indium Corporation is a materials refiner, smelter, manufacturer, and supplier to the global electronics, semiconductor, thin-film, and thermal management markets. Products include solders and fluxes; brazes; thermal interface materials; sputtering targets; indium, gallium, germanium, and tin metals and inorganic compounds; and NanoFoil. Founded in 1934 in Utica, New York, the company has global technical support and factories located in China, Germany, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.[2]

History

[edit]

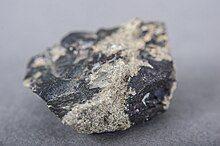

In 1863, the element indium was discovered by Professor Ferdinand Reich (1799–1882) and his assistant Hieronymous Theodor Richter (1824–1898) while at the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology, Germany. Reich, who was color blind, asked Richter to examine a yellow precipitate from some local zinc ores.[3] Spectrographic studies for thallium on the sample of sphaleritic ore revealed some undiscovered indigo-blue lines. That newly discovered element was named indium for the characteristic lines of its spectrum.[4]

Other chemists began working with indium to identify its properties. In 1864, J. A. R. Newlands made an early prediction that "when the equivalent of indium is determined, it will be found to bear a simple relation to the elements of the group to which it will be assigned."[5] R. E. Myer's work, as early as 1868, noted that when potassium cyanide is added to a solution of indium salt and boiled, the indium is precipitated out as the hydroxide, an early test that would lead to electrodepositing the metals many decades later.[6]

Reich and Richter were meant to present an ingot of indium at The International Exposition of 1867 (the second World's Fair) in Paris, but, fearing its theft, they instead displayed an 0.5 kg ingot of lead.[7]

Over the next 60 years, indium was considered a laboratory curiosity.[8] "In 1924, an order was placed with a prominent New York chemical supply company for a substantial quantity of indium. After several months of correspondence with foreign sources, one gram of the metal was located and purchased, it being all that was then available in the world. It was valued at ten dollars a gram."[9] In 1924, platinum was one of the most valuable metals at the time at $133.52 per ounce – the equivalent of $2,010.32 in 2021.[10] Indium was 212 percent more valuable.

Dr. William S. Murray, Daniel Gray, and John Dyer, Jr.

[edit]

Dr. William Stanley Murray (1887-1972) was born in Stillson Hill,[11] Warren County, Pa., just across the New York state line from Chautauqua County, the westernmost county in New York.[9] He was the son of George Campbell, who was engaged in the oil production business, and Armeina (Kay) Murray.[12]

Dr. Murray matriculated at Colgate University in Hamilton, N.Y., studying chemistry under the tutelage of Profs. Dr. Joseph Frank McGregory (1855-1934)[13] and Roy Burnett Smith (1875-1940).[14] Dr. McGregory shared of his pupil: "He couldn't be kept within the confines of any course so we just gave him a laboratory desk and didn't bother him."[9] "We just turned him loose to investigate, because he seemed happy to tackle new and untried problems."[15] Dr. Murray graduated with a bachelor's of science degree in 1910. He joined the university's board of trustees in 1926,[12] and on October 15, 1939, Dr. Murray was awarded a doctor of science from the university for his contributions in developing commercial uses of indium.[16][17]

In 1910 Dr. Murray joined the Utica Pipe Foundry as a chemist. It was located at the corner of Broad Street and Dwyer Avenue in Utica, sharing the opposite corner block occupied by the Willoughby Factory. When the foundry went bankrupt in January 1914,[18] Dr. Murray became a consulting chemist for Oneida Community.[12] He also established his own firm, William S. Murray, Inc. – consulting engineers specializing in chemistry[11] – which he used to render valuable assistance to other companies during World War I.[19] The first financial backer of his new enterprise was Francis F. Despard, a Utica, N.Y. business person.[20]

On June 28, 1913, Dr. Murray married Margaret A. Collins (1888-1965) in Buffalo, N.Y. Margaret was an active and prominent leader in women's organizations in Utica, and was a school teacher for several years. The couple had two children: George C. Murray (1917-1996)[21] – a graduate of Colgate University and an employee at the Indium Corporation of America, and Margaret Kay Murray (1919-2003)[21] – a graduate of Vassar College.[12] Within a month of receiving her degree, Margaret was in charge of a laboratory for the Camden Wire Co., Inc. of Camden, N.Y., and joined her father as a consultant at William S. Murray, Inc. to provide technical assistance to many companies.[19]

Daniel Gray (1889-1973) was born on November 1, 1889, in Chicago, Ill., the son of Christian N.E. Gray and Elizabeth Ann Olsen.[22][23] Daniel attended James Millikin University, Decatur, Ill.[24] In 1920, he wed Roberta Faith (1897-1977), and the couple had four children; three died in infancy.[25]

John Robert Dyer, Jr., (1910-1982) was born on October 17, 1910, in Yardley, Pa., the second of three sons to John R., Sr. (1880-?) and Ella (Keebler) Dyer (1880-?).[26] In 1923, he moved to and attended school in Clayville, N.Y. (now Sauquoit Valley) before transferring to Utica Free Academy (approximately 10 miles away) and graduating in 1928.[15] On June 2, 1932, he graduated with a degree in "Chemistry, Dyeing, and Printing" from The Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, Philadelphia, Pa. He served as vice-president of the school's class of 1931–1932.[27] On February 3, 1940, he married Ruth Caroline Bailey in Utica. The couple had one son: John R. Dyer, III.[28]

1920s

[edit]In 1924, Dr. Murray and Gray – Oneida Community-affiliated employees (later named Oneida Limited) – began working independently, and at times together, to study indium in hopes of discovering ways to process and use it for a variety of solutions in everyday life. When they first looked into indium as a valuable stabilizing element, four elementary textbooks were examined. Only one of them listed the element, and it mentioned indium as being "'a member of the aluminum family' and dismissed the subject."[29]

Dr. William Stanley Murray, director of research, and Technologist Daniel Gray soon began to research and devise multiple processes to alloy, electroplate, and electrodeposit with indium while working at the silver-plated flatware and hollow-ware manufacturer. Their first significant application of indium was a process to stabilize non-ferrous metals.[30]

In 1926, with the global supply of indium in trace amounts, Dr. Murray worked diligently to identify indium in mines throughout North America. In cooperation with the technologic staff at the Salt Lake City, Utah, station of the Bureau of Mines, they conducted a search for a commercial source of indium.[31] In one day, Dr. Murray and employees at Oneida Community spectroscopically studied thousands of samples of zinc, silver, gold, and lead ore, all resulting in no presence of indium.[29] "But after much trial and error, Dr. Murray found that indium could be extracted commercially from zinc ore mined in Chloride, Ariz. – a one-time silver mining camp in Mohave County that is considered the oldest continuously inhabited mining town in the state – located just north of Kingman, Ariz."[32] " … He and the Oneida Community began working with the Anaconda Mining Company of Great Falls, Mont., to secure commercial supplies of the metal."[33] At one of its abandoned mines (now named Twentieth Century Mine / Big Boy Mine), on property owned by George A. Beebe, in the Cerbat Mining District near Kingman, Dr. Murray led the search and found indium in a viable quantity to be commercially produced.[4] The property was purchased by Dr. Murray in 1926 and later transferred to Indium Corporation of America.[34][35] Initially, the combined search effort by Dr. Murray, the Salt Lake City Bureau of Mines' staff, and Anaconda Mining Co. staff led to the discovery of 35,000 tons of indium-rich ore that was blocked out.[31] In 1927, of 1,000 tons of zinc ore mined in Kingman, 250 ounces of indium was produced (0.78 percent).[4]

Initial patent efforts by Dr. Murray were taken skeptically by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. "[Dr. Murray] found that officials there did not take him too seriously, commenting that it was not so important because there appeared to be so little indium available. Murray reached into a bag he was carrying and produced a chunk of indium the size of a small loaf of bread – valued then at many thousands of dollars. That settled the matter and the government officials quickly realized he knew what he was talking about."[20] Between 1926 and 1934, either Drs. Murray or Gray were named on all U.S. patent applications applied for and issued related to indium: they co-authored four patent applications; additionally, Dr. Murray submitted four solo applications and Daniel submitted three.[36] These include a process to produce tarnish-resisting silver and silver plate [37] and a process to obtain indium and zinc from ore (1932).[38] Richard Orcutt Bailey, also employed at Oneida Community during the time period of 1926–1934, was also listed as an inventor of a number of patents with Dr. Murray and Gray, a majority of them involving a method of producing tarnish-resisting silver and silver plate.[39]

1930s

[edit]Daniel Gray began work in 1932 on one of the first commercial uses for indium: adding it as a dental alloy. Small quantities of indium harden and strengthen a metal to which it is alloyed, and it increases tarnish and corrosion resistance. As an example, gold-indium alloys – when used in denture castings – are smooth, dense, lustrous, and highly resistant to discoloration. The addition of indium to dental-gold solders provides increased fluidity, improved tensile strength, and gives greater bonding qualities and exceptional durability.[31]

On May 12, 1933, Dr. Murray delivered a lecture on indium to the Clarkson University Student Chapter of the AIChE (American Institute of Chemical Engineers) in Potsdam, N.Y. During the lecture, he exhibited a piece of indium weighing 125 grams – valued at $1,250 in 1933 (approximately $26,250 in 2022).[40] Several graduates of Clarkson University would join the Indium Corporation of America in the subsequent eight decades, including future company president and owner William N. Macartney, Jr., who graduated from the university in 1928.[41]

"On March 13, 1934 – armed with a unique product, protected intellectual property, a proven research team, and a secure supply of raw material – Dr. Murray, the Oneida Community, and Anaconda Mining Company formed The Indium Corporation of America."[42] Its management team included President Dr. William S. Murray, Vice President J. Robert Dyer, Jr., and Research Director Daniel Gray. The new business began operations in Dr. Murray's garage located at 805 Watson Place, Utica.[43]

On Saturday, April 28, 1934, Gray attended the 65th general meeting of the Electrochemical Society in Asheville, N.C., of which he is a member, and presented the first published paper on indium: The Electrodeposition of Indium from Cyanide Solutions.[44]

The first commercial customer of the Indium Corporation of America was Capt. R. V. Williams of Buffalo, head of the Williams Gold Refining Co., who purchased 0.5oz. of indium on July 21, 1934.[20]

Outside of his work for the Indium Corporation of America, Dr. Murray was engaged in multiple projects, including one to help solve the murder of at least 17 people. Just 14 months after the repeal of the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (better known as Prohibition), illicit liquor was found to be the cause of death for at least 17 people in Utica, N.Y. in January 1935. Dr. Murray – assisting federal, state, and local authorities – discovered that the organs of the first two victims who had ingested the poison liquor contained a large amount of wood alcohol.[45] A few years later, Dr. Murray was contracted by the Dairymen's League Co-Operative Association of New York to invent a moldable casein composition.[46] A Utica-based tannery was court-ordered to cease operations due to its waste run-off polluting a local stream. Dr. Murray obtained a 30-day stay by creating a method of solidifying the waste material. He applied elements of that same process to derive a casein plastic from milk; his process for the Dairymen's League changed the natural milk sugar to aldehyde in the presence of casein – a method that produced casein plastic without formaldehyde hardening, a long and costly process. The intense need of Indium Corporation materials for World War II prevented further development of Dr. Murray's new process, and the global adoption of synthetic plastics post-WWII drastically curtailed the use of casein.[47]

Originally applied for on November 26, 1934, Dr. Murray was awarded a patent for a "Process For Making Indium-Containing Glass" on May 26, 1936. The process produces a clear, transparent, yellow-tinted glass by heating glass with indium sesquioxide (In2O3) and various other materials.[48]

On December 15, 1936, Dr. Murray was unanimously elected to serve as chairman of the New York Republican State Committee,[49] succeeding Melvin C. Eaton (1934-1936), another chemist who would later serve as president at the Norwich Pharmacal Company in Norwich, N.Y. Dr. Murray served in this capacity from 1936 to 1940.[50][51]

In the first issue in 1938 of the Journal of the American College of Dentists, Dr. Murray, Gray, and Indium Corporation of America are acknowledged by Reginald V. Williams, A.C., of Williams Gold Refining Co. of Buffalo in his study "Use of Indium in Dental Alloys" for "their assistance in the preparation of pure indium, the special equipment which they made available, and the physical testing which they conducted." In the study, Williams exudes the virtues of indium, writing: "The rare metal indium is softer than lead, lighter than zinc, more lustrous than silver, as untarnishable as gold."[52]

On October 15, 1939, Dr. Murray – who served on the board of trustees at Colgate University – was awarded a doctor of science from that university's President George Barton Cutten for his contributions in developing commercial uses of indium.[53][17] The William S. Murray Fund was later established (1952) at Colgate University to provide sustaining support for the general operating expenses of the university.[54]

American Inventor and Goldsmith Isaac Babbitt (1799-1862) invented Babbitt metal or bearing metal in 1839, which is a blanket term for several alloys. These alloys were used to reduce bearing friction. Approximately 100 years later, J. Robert Dyer, Jr. developed an improved process to plate bearings with indium. A patent application was submitted on November 30, 1940, and approved by the U.S. patent office on July 27, 1943, for "Bearing and Like Article" that outlined a process for lead-based bearings in high-powered internal combustion engines to be electroplated with a thin film of indium which gives the bearing excellent resistance to fatigue failure and to corrosion.[55] It was the company's first large-scale application.

1940s

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2022) |

In 1940, Indium Corporation of America expanded its presence with a new office opened in New York City to support market development and promotional efforts. Marie Thompson Ludwick was named office manager, and directed the advertising and sales promotion program. Over the years, she published several bibliographies on indium, including Indium in 1942 which was cited by the U.S. Department of Commerce's 1943 research paper: "Thermal Expansivity and Density of Indium."

On May 1, 1941, the company began using its Pioneers in Element 49 logo. This trademark was used on metallic indium, indium alloys, and amalgams. The black circle logo with a stagecoach and the number 49 (to signify element 49 on the periodic table) is eventually assigned serial number 399,656 by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on January 26, 1943. The trademark was renewed on January 26, 2013.[56][57]

"Interest in indium and requests for experimental work … expanded so greatly, the establishment of a laboratory in New York became imperative." A new development laboratory to address requests from both industry and various government agencies was established in 1941 at the Electrical Testing Laboratories,[58] East End Avenue at 79th St., New York, N.Y.[59] Work at the new lab is commissioned by the U.S. Bureau of Conservation of Materials and includes the production of hundreds of samples for varied industries, including bearings for machinery, piston rings, valves for industrial pumps, bushings and other moving parts for machinery, as well as "hot-dip" coatings for metallic surfaces.[8]

Total domestic output of indium in 1941 was approximately 21,700 troy ounces. It tripled to 65,000 troy ounces produced in the U.S. in 1942, and tripled again in 1943.[60] Indium Corporation was the principal distributor of indium in the U.S., and the Anaconda Copper Mining Co. led all indium production from zinc and lead operations.[61] In 1942, electrolytic-grade indium (99.9 percent pure) was $30 per ounce.[62]

William "Mac" N. Macartney, III (1941-2021) was born on December 16, 1941, in Utica, the son of William N. Macartney, Jr. and Martha Smith. He would later pursue undergraduate studies at Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pa., and then attend Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., graduating from Cornell's Graduate School of Business and Public Administration (now named the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management) in 1966 with his M.B.A.

On January 1, 1942, all automobile sales – as well as the delivery of cars purchased prior to that date – were halted by an order from the U.S. Office of Production Management (OPM). President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the War Production Board (WPB) on January 16, 1942, which superseded the Office of Production Management. The WPB regulated the industrial production and allocation of war materials and fuel, including the rationing of vital materials, such as metals, rubber, and oil. As a result, virtually all manufacturers ended their production of automobiles from February 22, 1942, to October 1945.[63]

To meet the initial order by OPM, U.S. auto manufacturer Studebaker began to use indium to plate its automobile bumpers.

"Japan's sneak attack on Pearl Harbor would soon bring almost all automobile production to a government-imposed standstill. Before taking this drastic step, however, officials sought to conserve certain critical metals like chromium, nickel, and stainless steel by requiring most bright work to be eliminated. (The bright trim on completed cars still in stock had to be painted over.) … In order to provide vehicles that would approximate the beauty of their more glittery predecessors, Studebaker did much research on the use of non-critical metals like indium silver, and utilized baked-enamel finishes in colors that would offer pleasing contrast to that of the body."[64]

The majority of indium produced between 1942 and 1945 was used in the war effort. J. Robert Dyer, Jr.'s process to plate bearings with indium would lead the company's production through 1945. Dyer said the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Co. approached the Indium Corporation in 1938 for help identifying a protective plating treatment for bearings. "It turned out that indium-plated bearings were so much better than any others at the time, they were specified for Army and Navy aircraft engines throughout World War II,"[65] Dyer said. So, cadmium-nickel and copper-lead bearings for aircraft, truck, and marine engines were coated with indium to resist the corrosive action of acids in lubricants. The life of bronze bearings in a certain heavy-duty screw machine was lengthened greatly by indium treatment.[62]

On Thursday, November 12, 1942, those wartime efforts were lauded when Indium Corporation and its employees were commended for their "past accomplishments in the production field and inspiration for continual support to the armed forces." Col. Samuel R. Brentnall, Production Engineering Section of the U.S. Army Air Corps, presented Dr. Murray with the Army-Navy Production Award (the E pennant) at the Murray home (1530 Sunset Ave./805 Watson Place, Utica). The small lapel pin bearing the "E" symbol was presented to Dr. Murray and 10 employees by Lt. Hershel L. Mosier, U.S.N.R., former Colgate University alumni secretary.[66] Receiving the pins on behalf of the employees was Chemist Archie N. (Norman) Daymont.

Less than one week later, Dr. Murray and Indium Corporation were featured in a Time magazine article about the "once-rare" metal that "makes soft metals hard, dull ones bright, and does many an odd job in stretching the supply of critical materials."[32]

In January 1943, the Indium Corporation of America loaned a rod of cast indium to the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to determine the thermal expansion and density of indium.[58] The NBS is tasked by the U.S. Congress to develop and maintain the national standards of measurement, and the determination of physical constants and properties of materials.[67] A chemical analysis by R.K. Bell of the NBS estimated the indium content of the rod to be 99.9 percent; linear expansion of indium is defined by Lt=L0[1+ (28.93t + 0.0134t2)10−6]; the density of cast indium is 7.281g/cm3 at 22.6 °C.

In 1943, a new manufacturing facility was established at 1676 Lincoln Ave., Utica, N.Y.[43]

On display at the 25th annual meeting of the National Metal Congress at the Palmer House, Chicago, Ill. (October 18, 1943) was an indium-alloy-finished propeller blade of hollow steel. The blade was the result of two years of experimental work between Indium Corporation and the Propeller Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. That latest development by Indium Corporation was announced in Business Week's October 23 issue of 1943. "Indium Scores" was the lead piece in the publication's "Production" section, but few other details about the process could be released due to "severe editing by the military censorship."[68] The article also shares that steel bearings electroplated with silver are then electroplated with indium at a rate of 0.00016 troy ounces of indium per square inch, an economical cost at the time of $1.50 to provide abrasion and corrosion resistance for an aircraft's main bearing.

In a piece for Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology (1944), Dr. Murray wrote about the importance of indium in the aviation industry for a meeting of the American Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences. " … [For] it is in the aviation industry that indium has received its greatest acclaim and has contributed so materially to the perfection of vital war machines," Dr. Murray noted. It has long since passed the experimental stage "and has become a vital factor in both power plants and airscrews."[69]

On July 25, 1944, Dr. Murray was granted a patent for "Operation and Lubrication of Mechanical Apparatus." Originally applied for four years prior, this is one of a couple of patents by Indium Corporation of America that addresses using indium as an additive ingredient in combustible fuel (gasoline, indium trimethyl) and lubricants (colloidal indium, indium phenyl stearate, indium hydroxide) to reduce the formation of sludge and acidic residues while increasing lubricity and, therefore, efficiency and performance.[70]

In 1945, Ludwick was elected secretary and assistant to the president at the Indium Corporation of America. She had previously managed the New York Office and penned many scientific articles as well as complete bibliographics on the subject of the metal indium. "This promotion is in recognition of her work in the field of metallurgy, one in which few women are engaged in executive capacities."[71]

In 1946, total employees included five chemists, three metallurgists, three technical personnel, and six additional employees.[72]

Throughout the 1940s, The Indium Corporation of America discovered or refined the following uses of indium:[32]

- Copper clad and cadmium bearings in aviation and diesel engines are highly resistant to acid corrosion of lubricating oil when they are treated with and indium or an indium alloy coating

- 60Ag40In alloy has the same luster as sterling silver, but is more than three times as hard

- Indium-gold dental alloys stand up well to molar pressure and resist the tarnishing action of acids

- Although the luminosity of reflectors in searchlights and headlights made with indium alloys is slightly less than those made with silver and certain other materials, they retain a uniform value for a much longer period of time

- As a substitute for chromium and nickel plating, indium takes a high polish, is resistant to discoloration, and when electrolytically deposited it diffuses with the underlying non-ferrous metals to form a protective coating

References

[edit]- ^ (December 1, 2017). "Indium announces senior promotions". Rome Sentinel. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ "Who We Are". Indium Corporation. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "49. Indium - Elementymology & Elements Multidict". www.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b c Mines, United States Bureau of (1965). Bulletin. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Mellor J. W. (1924). A Comprehensive Treatise On Inorganic And Theoretical Chemistry Vol-v (1924).

- ^ "The Electrodeposition of Indium from Cyanide Solutions | Gray, Daniel | download". ur.booksc.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ Renouf, Catherine (October 2012). "A touch of indium". Nature Chemistry. 4 (10): 862. Bibcode:2012NatCh...4..862R. doi:10.1038/nchem.1460. ISSN 1755-4349. PMID 23001002.

- ^ a b Ludwick, Maria Thompson (1959). Indium: Discovery, Occurrence, Development, Physical and Chemical Characteristics and a Bibliography of Indium 1863-1958 Inclusive (2nd ed.). p. 11.

- ^ a b c French, Sidney J. (May 1934). "A story of indium". Journal of Chemical Education. 11 (5): 270. Bibcode:1934JChEd..11..270F. doi:10.1021/ed011p270. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Bradley, Walter Wadsworth (1925). California Mineral Production for 1924. California State Printing Office.

- ^ a b "Murray Plans Drive to Unite G.O.P. Groups" (PDF). Fulton History. The Evening Recorder. December 15, 1936. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Galpin, William Freeman (1941). Central New York, an inland empire, comprising Oneida, Madison, Onondaga, Cayuga, Tompkins, Cortland, Chenango counties and their people. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. New York, Lewis Historical Pub. Co.

- ^ "Recent Deaths". Science. Vol. 80, No. 2077. 80 (2077): 353. October 1934. Bibcode:1934Sci....80..353.. doi:10.1126/science.80.2077.353. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Roy Burnett Smith (1875-1940) buried in Colgate University Cemetery located in Madison County, New York | People Legacy". peoplelegacy.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b Townsend, Ted (September 21, 1951). "Utican's Persistence Resulted in Use of Indium in Industry". Fulton History. Utica Daily Press. p. 23. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Colgate University 1939 Yearbook (Hamilton, NY) - Full Access". www.yearbookinfo.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b "Scientific Notes and News". Science. 90 (2338): 368–370. 1939. doi:10.1126/science.90.2338.368.b. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1666477. S2CID 239783260.

- ^ "Willoughby Company Part 3, Francis D. Willoughby, Willougby-Owen Co., R.M. Bingham & Co., Willoughby-bodied, Edward A. Willoughby - CoachBuilt.com". www.coachbuilt.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b Stanley, William; Kay, Margaret (April 1943). "Fathers and Daughters in Chemistry". Chemical & Engineering News. 21 (8): 548. doi:10.1021/cen-v021n008.p548. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ a b c "Murray Indium to Improve Post-War Cards - Product Toughens Metals". Fulton History. Utica Observer. August 1943. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "George Murray from Ward 11 Utica in 1940 Census District 67-59". www.archives.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Daniel Gray". AncientFaces. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "FamilySearch.org". ancestors.familysearch.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Literary Editor". Carli Digital Collection. Vol. 9, November 1. The Decaturian. September 12, 1911. p. 4. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "FamilySearch.org". ancestors.familysearch.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Keebler Family History". The Tin Type Shop. June 25, 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-08-07. Retrieved August 6, 2021.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (1932). Commencement program, 1932. University Libraries University of the Arts (Philadelphia). Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art.

- ^ "Obituaries". Fulton History. Utica Daily Press. March 16, 1982. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Baldwin, Ellis K. (November 1943). "Meet The Indium Man". Google Books. Rotarian. p. 41. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Schwarz-Schampera, Ulrich (2014). "Indium" (PDF). Critical Metals Handbook. British Geological Survey. pp. 204–229. doi:10.1002/9781118755341.ch9. ISBN 978-0-470-67171-9.

- ^ a b c "Indium". Mineral Facts and Problems (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Mines. 1956. p. 368. Bulletin 556.

- ^ a b c "Science: Indium". Time. November 16, 1942. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "ONEIDA COUNTY. An Illustrated History. A publication of the Oneida County Historical Society - PDF Free Download". docplayer.net. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Letter from Harry C.J. Lennox, Arizona Small Mine Owners Assoc., to Arizona State Dept. of Mineral Resources" (PDF). State of Arizona Government. February 18, 1943. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Mine (Big Boy Mine), Cerbat, Cerbat Mining District, Wallapai Mining District, Cerbat Mountains (Cerbat Range), Mohave County, Arizona, USA". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Google Patents". patents.google.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ US 1719365, Daniel, Gray; Bailey, Richard O. & Murray, William S., "Tarnish-resisting silver and silver plate and processes for producing the same", published 1929-07-02, assigned to Oneida Community Ltd.

- ^ US 1847622, Murray, William S., "Process of obtaining indium and zinc from ores containing the same", published 1932-03-01, assigned to Oneida Community Ltd.

- ^ "Google Patents". patents.google.com. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Clarkson Integrator. (Potsdam, N.Y.) 1920-current, May 17, 1933, Image 2". Clarkson Integrator. No. 1933/05/17. Potsdam, NY. 1933-05-17. p. 2 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ "Fort Covington sun. (Fort Covington, N.Y.) 1934-1993, June 07, 1962, Image 1". Fort Covington Sun. No. 1962/06/07. Fort Covington, NY. 1962-06-07. p. 1 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ Oneida County: An Illustrated History. Oneida County Historical Society. Retrieved 2022-05-26 – via DocPlayer.

- ^ a b "Technical Milestones". Indium Corporation. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ Gray, Daniel (1934). "The Electrodeposition of Indium from Cyanide Solutions". Transactions of the Electrochemical Society. 65 (1): 377. doi:10.1149/1.3498045. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ "The Advance-news. (Ogdensburg, N.Y.) 1933-1935, January 30, 1935, Image 8". The Advance-News. No. 1935/01/30. Ogdensburg, NY. 1935-01-30. p. 8 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ US 2115316, Murray, William S., "Moldable casein composition", published 1938-04-26, assigned to Dairymen's League Co-operative Association

- ^ Sharma, Sanjay K.; Mudhoo, Ackmez (2011-06-20). A Handbook of Applied Biopolymer Technology: Synthesis, Degradation and Applications. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-345-8.

- ^ US 2042117, Murray, William S., "Process for making indium-containing glass", published 1936-05-26

- ^ "New York Republican State Committee Records, 1888-2001". M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives. University Libraries, University at Albany, State University of New York. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Ticonderoga sentinel. (Ticonderoga, Essex County, N.Y.) 188?-1982, December 17, 1936, Image 1". Ticonderoga Sentinel. No. 1936/12/17. Ticonderoga, Essex County, NY. 17 December 1936. p. 1 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ "The Advance-news. (Ogdensburg, N.Y.) 1933-1935, January 16, 1938, Image 5". The Advance-News. No. 1938/01/16. Ogdensburg, NY. 16 January 1938. p. 5 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ Williams, R.V. (March–June 1938). "Use of Indium in Dental Alloys" (PDF). Journal of the American College of Dentists. 5 (1–2): 94. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Colgate University 1939 Yearbook (Hamilton, NY)". Yearbook Info. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ Named Endowment Funds at Colgate University: The Foundation for Our Future. Colgate University. Retrieved 2022-05-26 – via Yumpu.

- ^ US 2325071, Murray, William S., "Bearing and like article", published 1943-07-27, assigned to Indium Corporation of America

- ^ "PIONEERS IN ELEMENT 49 Trademark of The Indium Corporation of America. Serial Number: 86334399". Trademark Elite Trademarks. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ "PIONEERS IN ELEMENT 49 - Indium Corporation of America, The Trademark Registration". USPTO.report. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ a b Hidnert, Peter; Blair, Mary Grace (June 1943). "Thermal Expansivity and Density of Indium" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards. 30 (6). U.S. Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards: 433. doi:10.6028/jres.030.029.

- ^ "Standing Committee" (PDF). Clearance, Marker, and Identification Lamps for Vehicles (After Market). U.S. Department of Commerce: 6. 1941.

- ^ Cleaves, Freeman (July 27, 1943). "A Dash of Rare Indium Toughens Other Metals for Wartime Jobs". Wall Street Journal. Adelphi University, Garden City, N.Y.: 1.

- ^ Minerals Yearbook. Bureau of Mines. 1945.

- ^ a b Minerals Yearbook. Bureau of Mines. 1943.

- ^ "Teachinghistory.org". teachinghistory.org. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ "1942 Studebaker Champion Update" (PDF). Retired State Police Association of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2022-05-26.[dead link]

- ^ "Syracuse Herald American Archives, Mar 7, 1982, p. 95". NewspaperArchive.com. 1982-03-07. Retrieved 2022-05-26.

- ^ "Divine Brothers, Indium Corporation Get Army-Navy E Award for Production Effort". Utica Observer-Dispatch. November 13, 1942. p. 1. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Standard Materials, Issued by the National Bureau of Standards, A Descriptive List With Prices (PDF). Vol. 241. U.S. Department of Commerce. March 12, 1962. p. 8.

- ^ "Business Week 1943-10-23: Iss 738". Business Week. No. 738. Bloomberg L.P. 1943-10-23.

- ^ Murray, William S. (1944-01-01). "Indium in Aviation". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology. 16 (11): 332–333. doi:10.1108/eb031194. ISSN 0002-2667.

- ^ US 2354218, Murray, William S., "Operation and lubrication of mechanical apparatus", published 1944-07-25, assigned to Indium Corporation of America

- ^ "Westfield Republican. (Westfield, N.Y.) 1855-current, August 01, 1945, Image 5". Westfield Republican. No. 1945/08/01. Westfield, NY. 1945-08-01. p. 5. ISSN 1071-1074 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ Read "Industrial Research Laboratories of the United States, Including Consulting Research Laboratories" at NAP.edu. 1946. doi:10.17226/18663. ISBN 978-0-309-29992-3.