India–South Korea relations

| |

India |

South Korea |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of India, Seoul | Embassy of South Korea, New Delhi |

| Envoy | |

| Amit Kumar | Lee Seong-ho |

India and the Republic of Korea (ROK) relations are the bilateral relations between The Republic of India and The Republic of Korea. Formal establishment of diplomatic ties between the two countries occurred on 10 December 1973. Since then, several trade agreements have been reached such as the Agreement on Trade Promotion and Economic and Technological Co-operation in 1974, the Agreement on Co-operation in Science & Technology in 1976, the Convention on Double Taxation Avoidance in 1985, and the Bilateral Investment Promotion/Protection Agreement in 1996.

Trade between the two nations has increased greatly from $530 million during the fiscal year of 1992–1993 to billions during the fiscal year of 2006–2007.[1] It further increased to US$17.6 billion by 2013.

India–South Korea relations have advanced particularly due to united interests, mutual goodwill, and high-level exchanges. South Korea is currently the fifth largest source of investment in India.[2] Korean companies such as LG, Samsung and Hyundai have established manufacturing and service facilities in India, and several Korean construction companies won grants for a portion of the many infrastructural building plans in India such as the National Highways Development Project.[2] Tata Motors' purchase of Daewoo Commercial Vehicles at the cost of US$102 million highlights one of India's many investments in Korea which consist mostly of subcontracting.[2]

The Indian community in Korea is estimated to be around 8,000 people, specifically businesspeople, IT professionals, scientists, research fellows, students, and workers; there are about 150 businesspeople dealing mainly in textiles, and over 1,000 IT professionals and software engineers have recently come to Korea to work, including in large conglomerates such as Samsung and LG. Additionally, there are about 500 scientists and post-doctoral research scholars in Korea.[3]

Pre-modern relations

[edit]

Trade relations

[edit]Indian diamond drilled carnelian beads have been discovered in Korea dating back to the proto three kingdoms period (100–669 CE).[5]

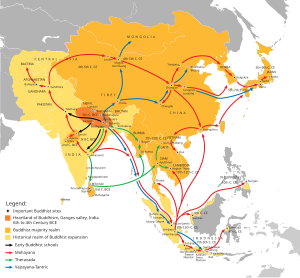

Buddhism in Korea

[edit]Centuries after Buddhism originated in India, Mahayana Buddhism arrived in China through the Silk Road in the first century CE via Tibet, then to the Korean peninsula in the third century during the Three Kingdoms period, after which it was transmitted to Japan.[6]

The Samguk yusa records the following three monks as being among the first to bring Buddhist teaching, or Dharma, to Korea: Malananta (late fourth century), an Indian Buddhist monk who brought Buddhism to Baekje in the southern Korean peninsula; Sundo, a Chinese Buddhist monk who brought Buddhism to Goguryeo in northern Korea; and Ado, a Chinese Buddhist monk who brought Buddhism to Silla in central Korea.[7][8] In Korea, it was adopted as the state religion of three constituent polities of the Three Kingdoms period: the Goguryeo (Gaya) in 372 CE, the Silla in 528 CE, and the Baekje in 552 CE.[6]

In 526 CE, Korea monk Gyeomik went to India to learn Sanskrit and study the monastic discipline Vinaya, after which he founded the Gyeyul (Korean: 계율종; Hanja: 戒律宗; RR: Gyeyuljong) branch of Buddhism which specializes in the study of Vinaya that derives directly from the Indian Vinaya School.[9]

The historical fact that people on the Indian subcontinent were familiar with Korea's customs and beliefs is amply testified by the records of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Yijing who reached India in 673. Yijing writes that Indians regarded Koreans as "worshipers of the rooster", a concept about Koreans that had been grounded in a legend of the Silla dynasty.[10]

A famous Korean visitor to India was Hyecho, a Korean Buddhist monk from Silla, one of the three Korean kingdoms of the period. On the advice of his Indian teachers in China, he set out for India in 723 CE to acquaint himself with the language and culture of the land of the Buddha. He wrote a travelogue of his journey in Chinese, Wang ocheonchukguk jeon, or An account of travel to the five Indian kingdoms. The work was long thought to be lost; however, a manuscript turned up among the Dunhuang manuscripts during the early 20th century.

A rich merchant from the Ma'bar Sultanate, Abu Ali (P'aehali) 孛哈里 (or 布哈爾, Buhaer), was associated closely with the Ma'bar royal family. After falling out with them, he moved to Yuan dynasty China, married a Korean woman, and received a job from the Mongol emperor. His wife was formerly married to Sangha, a Tibetan,[11] and her father was Ch'ae In'gyu during the reign of Chungnyeol of Goryeo, recorded in the Dongguk Tonggam, Goryeosa and Liu Mengyan's Zhong'anji.[12][13]

Modern relations

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]A 2005 government survey indicated that about a quarter of South Koreans identified as Buddhist.[14] However, including the people outside of the practicing population who are deeply influenced by Buddhism as part of Korean traditions, the number of Buddhists in South Korea is considered to be much larger.[15] Similarly, in officially atheist North Korea, while Buddhists officially account for 4.5% of the population, a much larger number (over 70%) of the population are reported to be influenced by Buddhist philosophies and customs.[16][17]

In 2001, a memorial of Heo Hwang-ok from 48 CE, who is believed to be a princess of Indian origin named Suriratna, was inaugurated by a Korean delegation in the city of Ayodhya, India, which included over a hundred historians and government representatives.[18]

In 2016, a Korean delegation proposed to develop the memorial; the proposal was then accepted by the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav.[19][20] Kim Jung-sook, first lady of South Korea, later inaugurated the groundbreaking of the Queen Heo Hwang-ok memorial with Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath in November 2018, with plans for completion by 2020.[21] Gimhae, which already has a tomb and pagoda of Queen Heo Hwang-ok, is now constructing 3000 square meters of a museum and exhibition hall.[22]

Strategic partnership

[edit]During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, South Korean businesses sought to increase access to the global markets and began trade investments with India.[1]

The India–Republic of Korea Joint Commission for bilateral co-operation was established in February 1996, which has been chaired by the external affairs minister and the minister of foreign affairs and trade from both countries.[23] So far, six meetings of the Joint Commission have been held, with the last one held in Seoul in June 2010.

In an interview with the Times of India, former Korean president Roh Tae-woo voiced his opinion that co-operation between India's software and Korea's IT industries would bring successful outcomes.[24] The two countries agreed to shift their focus to the revision of the visa policies between the two countries, expansion of trade, and establishment of a free trade agreement to encourage further investment between the two countries.

In February 2006, there was a state visit to Korea by Indian President Abdul Kalam which heralded a new phase in India–Korea relations. It led to the launch of a joint task force to conclude a bilateral Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), which was signed by Minister for Commerce and Industry Anand Sharma in Seoul on 7 August 2009.

Korean President Lee paid a landmark visit to India during Republic Day celebrations on 26 January 2010, when bilateral ties were raised to the level of strategic partnership. One year later, in 2011, an Indian Cultural Centre was established in South Korea in April, and the Festival of India in Korea was inaugurated by Dr. Karan Singh, President of Indian Council for Cultural Relations, on 30 June, to revitalise the cultural relations between the two countries.

Indian president Pratibha Patil embarked on a state visit to Korea from 24 to 27 July 2011, during which the Civil Nuclear Energy Cooperation Agreement was signed. One year later, in June 2012, India, a major importer of arms and military hardware, planned eight warships from South Korea, but the contract ended in cancellation.[25]

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh paid an official visit to Seoul from 24–27 March 2012, pertaining to Nuclear Security Summits, which led to the deepening of bilateral strategic partnership that was forged during President Lee Myung-bak's state visit to India. An agreement on visa simplification was signed on 25 March in the presence of the two leaders at the Blue House. A joint statement was also issued during the prime minister's visit.

Former South Korean president Park Geun-hye visited India in 2014.

In July 2018, South Korean president Moon Jae-in and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi jointly inaugurated Samsung Electronics's smartphone assembly factory in Noida, the largest such factory in the world.[26]

In 2024, during the second 2+2 policy dialogue between South Korean and Indian research institutes in Seoul, Park Cheol-hee, Chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy, stated:[27]

In essence, South Korea and India share a lot of common qualities and external orientations, so the two countries are wonderful partners to work within a world of uncertainty, instability, and fluidity.

At the same event, Vijay Thakur, Director General of the Indian Council of World Affairs, stated:[27]

Strengthening the India-South Korea partnership in the region and in Indo-Pacific is of strategic importance for both economies.

Trade

[edit]| Year | Total trade | Growth % | Indian exports to ROK | Growth % | ROK Export to India | Growth% |

| 2007 | 11,224 | 22.35% | 4,624 | 27.03% | 6,600 | 19.3% |

| 2008 | 15,558 | 39.00% | 6,581 | 42.32% | 8,977 | 36% |

| 2009 | 12,155 | -21.88% | 4,142 | -37.06% | 8,013 | -10.7% |

| 2010 | 17,109 | 40.76% | 5,674 | 36.98% | 11,435 | 42.7% |

| 2011 | 20,548 | 20.10% | 7,894 | 39% | 12,654 | 10.7% |

| 2012 | 18,843 | -8.30% | 6,921 | -12.3% | 11,922 | -5.8% |

| 2013 | 17,568 | -0.07% | 6,183 | -10.7% | 11,385 | -4.5% |

| 2014 | 18,060 | 2.8% | 5,275 | -14.6% | 12,785 | 12.4% |

| 2015 | 16,271 | -9.9% | 4,241 | -19.6% | 12,030 | -5.9% |

| 2016 | 15,785 | -2.9% | 4,189 | -1.2% | 11,596 | -3.6% |

| 2017 | 20,005 | 26.7% | 4,949 | 18.1% | 15,056 | 29.8% |

| 2018 | 21,491 | 7.4% | 5,885 | 18.9% | 15,606 | 3.7% |

| 2019 | 20,663 | -3.87% | 5,566 | -5.40% | 15,097 | -3.29% |

| 2020 | 16,852 | -22.61% | 4,900 | -12.0% | 11,952 | -20.8% |

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Lokesh, Chandra (1970). India's contribution to world thought and culture. Madras: Vivekananda Rock Memorial Committee.

- Jain, Sandhya, & Jain, Meenakshi (2011). The India they saw: Foreign accounts. New Delhi: Ocean Books. (Vol. I contains material about Korean (and Chinese) Buddhist pilgrims to India.)

- Kumar, Rajiv (2018). "South Korea's New Approach to India." Observer Research Foundation

- Kumar, Rajiv (2015). "Explaining the origins and evolution of India’s Korean policy," International Area Studies Review, vol. 18(2), pp. 182–198.

- Kumar, Rajiv (2015). "Korea’s Changing Relations with the United States and China: Implications for Korea- India Economic Relations," Journal of Asiatic Studies, pp. 104–133 (Asiatic Research Center, Korea University)

References

[edit]- ^ a b IDSA publication Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c FICCI info Archived 2008-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sorry for the inconvenience". April 2016.[dead link]

- ^ Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Glover, Lauren; Kenoyer, J. M. (2019). "Overlooked Imports: Carnelian Beads in the Korean Peninsula". Asian Perspectives. 58 (1): 180–201. doi:10.1353/asi.2019.0009. hdl:10125/76776. ISSN 1535-8283. S2CID 166339176.

- ^ a b Lee Injae, Owen Miller, Park Jinhoon, Yi Hyun-Hae, 2014, Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press, pp. 44–49, 52–60.

- ^ "Malananta bring Buddhism to Baekje" in Samguk Yusa III, Ha & Mintz translation, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Kim, Won-yong (1960), "An Early Gilt-bronze Seated Buddha from Seoul", Artibus Asiae, 23 (1): 67–71, doi:10.2307/3248029, JSTOR 3248029, pg. 71

- ^ The Buddhist Religion: a historical introduction. Richard H. Robinson, Willard L. Johnson, Sandra Ann Wawrytko. Wadsworth Pub. Co., 1996

- ^ Korea Journal Vol.28. No.12 (Dec. 1988)

- ^ Shaykh 'Âlam: the Emperor of Early Sixteenth-Century China, p. 15.

- ^ Angela Schottenhammer (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4.

- ^ SEN, TANSEN. 2006. "The Yuan Khanate and India: Cross-cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries”. Asia Major 19 (1/2). Academia Sinica: 317. JSTOR.

- ^ According to figures compiled by the South Korean National Statistical Office."인구,가구/시도별 종교인구/시도별 종교인구 (2005년 인구총조사)". NSO online KOSIS database. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ^ Kedar, Nath Tiwari (1997). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0293-4.

- ^ Religious Intelligence UK Report

- ^ [1] Archived 2016-01-05 at the Wayback Machine North Korea, about.com

- ^ Korean memorial to Indian princess, 6 March 2001, BBC

- ^ UP CM announces grand memorial of Queen Huh Wang-Ock Archived 2019-12-12 at the Wayback Machine, 1 March 2016, WebIndia123

- ^ Choe, Chong-dae (12 July 2016). "Legacy of Queen Suriratna". The Korea Times. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Ahuja, Sanjeev K (19 August 2020). "Coming soon, Musical on Queen Huh of Korea; Princess Suriratna of Ayodhya". Asian Community News. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Ahuja, Sanjeev K (23 December 2019). "Korea to have first museum of Indian princess Suriratna". Asian Community News. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "India-Korea cooperation must for Indo-Pacific peace". The Sunday Guardian. 3 March 2024.

- ^ Blue House commentary Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "India to buy 8 warships from South Korea for Rs 6,000 crore". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "Samsung opens world's biggest smartphone factory in India". Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Why Korea-India partnership matters in era of uncertainties". The Korea Herald. 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Embassy of India, Seoul, Republic of Korea : India – RoK Trade and Economic Relations". www.indembassyseoul.gov.in. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

External links

[edit]- Coping with Giants: South Korea’s Responses to China’s and India’s Rise by Chung Min Lee, Strategic Asia 2011–12: Asia Responds to Its Rising Powers – China and India (September 2011)

- List of Agreements signed between India and South Korea in May 2015

- Rajiv Kumar. "Explaining the origins and evolution of India’s Korean policy", International Area Studies Review, June 2015; vol. 18(2), pp. 182–198.

- Rajiv Kumar. "Korea's Changing Relations with the United States and China: Implications for Korea- India Economic Relations," Journal of Asiatic Studies, 2016 vol. 58(4), pp. 104–133 (Asiatic Research Center, Korea University)