Territory of the Islamic State

Islamic State الدولة الإسلامية ad-Dawlah al-Islāmiyah | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto: لا إله إلا الله، محمد رسول الله "Lā ʾilāha ʾillā llāh, Muhammadun rasūlu llāh" "There is no god but God; Muhammad is the messenger of God"[1] دولة الإسلام باقية وتتمدد Dawlat al Islam Baqiyah wa Tatamaddad "The Islamic State remains and expands"[1] خلافة على منهاج النبوة Khilafah ala Minhaj an-Nubuwwah "Caliphate Upon the Prophetic Methodology"[2][3] | |||||||||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||||||||

Seal:[5][6][7][8][9][10] | |||||||||||||||||

Greatest extension of the Islamic State. May 2015. | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized proto-state Designated as a terrorist organization | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Raqqa (2013–2017)[1] Mayadin (2017)[11] Hajin (2017–18)[12] Unknown (2018–present) | ||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Salafism) | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary Islamic theocratic self-proclaimed caliphate under a totalitarian dictatorship | ||||||||||||||||

• Caliph | Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurashi | ||||||||||||||||

• Head of the Shura Council | Abu Arkan al-Ameri | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Shura | ||||||||||||||||

| Establishment | War on Terror | ||||||||||||||||

• Established under the name of Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad | 1999 | ||||||||||||||||

• Joined al-Qaeda | October 2004 | ||||||||||||||||

• Declaration of an Islamic State in Iraq | 13 October 2006 | ||||||||||||||||

• Claim of territory in the Levant | 8 April 2013 | ||||||||||||||||

• Separated from al-Qaeda | 3 February 2014 | ||||||||||||||||

• Declaration of caliphate | 29 June 2014 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 July 2017 | |||||||||||||||||

• Capture of Baghuz Fawqani | 19 March 2019 | ||||||||||||||||

| 27 October 2019 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 February 2022 | |||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 2015 estimate | (near max extent): 8–12 million[13][14] | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+2 and +3 (EET and AST) | ||||||||||||||||

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) | ||||||||||||||||

| Drives on | Right | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Islamic State (IS) had its core in Iraq and Syria from 2013 to 2017 and 2019 respectively, where the proto-state controlled significant swathes of urban, rural, and desert territory, mainly in the Mesopotamian region.[14] Today the group controls scattered pockets of land in the area, as well as territory or insurgent cells[14][16] in other areas, notably Afghanistan, West Africa, the Sahara, Somalia, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[17] As of 2023, large swathes of Mali have fallen under IS control.[18]

In early 2017, IS controlled approximately 45,377 square kilometers (17,520 square miles) of territory in Iraq and Syria and 7,323 km2 of territory elsewhere, for a total of 52,700 square kilometres (20,300 sq mi).[14] This represents a substantial decline from the group's territorial peak in late 2014, when it controlled between 100,000 and 110,000 square kilometres (39,000 and 42,000 sq mi)[14][19] of territory in total.[14][20] IS territory has declined substantially in almost every country since 2014, a result of the group's unpopularity and the military action taken against it.[14] By late March 2019, IS territory in Syria was reduced to only the besieged 4,000 km2 (1,550 sq mi) Syrian Desert pocket.[21] The enclave was surrounded by Syrian government forces and its allies.[22][23][21] The Syrian military conducted combing operations and airstrikes against the pocket, but with limited success.[24][25] IS propaganda claims a peak territorial extent of 282,485 km2.[26]

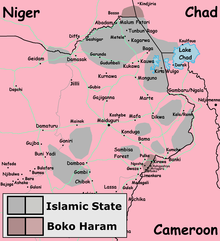

The majority of the Islamic State's territory, population, revenue, and prestige came from the territory it once held in Iraq and Syria.[14] In Afghanistan, IS mostly controls territory near the Pakistan border and has lost 87% of its territory since spring 2015.[14] In Lebanon, IS also controlled some areas on its border at the height of the Syrian war. In Libya, the group operates mostly as a moving insurgent force, occupying places before abandoning them again.[27] In Egypt, the group controls 910 km2 of land centered on the small city of Sheikh Zuweid, which represents less than 1% of Egypt's territory.[14] In Nigeria, Boko Haram (at the time an IS affiliate) controlled 6,041 km2 of territory at its maximum extent in 2014, though most of this area was lost amid military reversals and a split within Boko Haram between pro- and anti-IS factions.[14] By late 2019, however, IS's African forces had once again seized large areas in Nigeria;[28] as of 2021, IS's African forces still run their own administrations in territories they control.[29][30] As of 2022, most of IS's territory is confined to northeastern Nigeria and northern Mozambique, alongside large swathes of eastern Mali.[18]

Background

[edit]The fifth edition of the Islamic State's Dabiq magazine explained the group's process for establishing new provinces. Jihadist groups in a given area must consolidate into a unified body and publicly declare their allegiance to the caliph. The group must nominate a Wāli (Governor), a Shura Council (religious leadership), and formulate a military strategy to consolidate territorial control and implement Sharia law. Once formally accepted, IS considers the group to be one of its provinces and gives it support.[31] Dabiq has acknowledged support in regions including East Turkestan, Indonesia and the Philippines, and claimed that IS would eventually establish wilayat in these areas after forming direct relationships with its supporters there.[31]

Overview

[edit]IS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani said "the legality of all emirates, groups, states and organizations becomes null by the expansion of the khilafah's [caliphate's] authority and arrival of its troops to their areas."[32] IS thus rejects the political divisions established by Western powers during World War I in the Sykes–Picot Agreement as it absorbs territory in Syria and Iraq.[33][34][35] The Long War Journal writes that the logical implication is that the group will consider preexisting militant groups like Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) illegitimate if they do not nullify themselves and submit to IS's authority.[36]

While branches in Libya and Egypt have been very active and attempted to exercise territorial control, branches in other countries like Algeria and Saudi Arabia have been less active and do not seem to have a strong presence.[37][38]

Since 2022, there have been no further provinces officially announced by IS. This is despite the group receiving public pledges of allegiance from militants in countries like Somalia, Bangladesh and the Philippines, and subsequently releasing statements and videos from those regions through its official media channels.[39][40][41] Analyst Charlie Winter speculates that this is due to the lackluster performance of many of IS's existing provinces, and that IS's leadership seems to be identifying new affiliates as simply "soldiers of the caliphate."[42]

Loss of "caliphate" territory led IS to conduct more terrorist attacks abroad.[43]

Specific territorial claims

[edit]The Islamic State primarily claimed territory in Syria and Iraq, subdividing each country into multiple wilayah (provinces), largely based on preexisting governance boundaries.[44][45] The first territorial claims by the group outside of Syria and Iraq were announced by its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, on 13 November 2014, when he announced new wilayats, or provinces, in Libya (Wilayah Barqah, Wilayah Tarabulus, and Wilayah Fazan), Algeria (Wilayah al-Jazair), Sinai, Egypt (Wilayah Sinai), Yemen (Wilayah al-Yaman), and Saudi Arabia (Wilayah al-Haramayn).[46][47] In 2015, new provinces were also announced in the Afghanistan–Pakistan border (Wilayah Khurasan),[37] Northern Nigeria (Wilayah Gharb Ifriqiyyah),[48] the North Caucasus (Wilayah al-Qawqaz),[49] and the Sahel (Sahil).[50]

Kurdistan

[edit]In November 2014, the Islamic State released a video in which two of its militants stated that IS will make a province for Kurdistan if they capture it.[51]

Iraq and Syria

[edit]

When the Iraq-based insurgent group Mujahideen Shura Council announced it was establishing an Islamic State of Iraq in October 2006, it claimed authority over seven Iraqi provinces: Baghdad, Al Anbar, Diyala, Kirkuk, Saladin, Nineveh, and parts of Babil.[53]

When the group changed its name to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and expanded into Syria in April 2013, it claimed nine Syrian provinces, covering most of the country and lying largely along existing provincial boundaries: Al Barakah (al-Hasakah Governorate), Al Khayr (Deir ez-Zor Governorate), Raqqa, Homs, Halab, Idlib, Hamah, Damascus, and Latakia.[54] It later subdivided the territory under its control to create the new provinces of al-Furat,[45][55][56] Fallujah, Dijlah, and al-Jazirah.[57][58] On 9 December 2017 Iraqi military forces announced the war against IS in Iraq had been won and that they no longer controlled territory in Iraq. In June 2017 IS affiliate Khalid ibn al-Walid Army started referring to themselves as "Wilayat Hawran", one month later IS media started referring to all its claims in Syria as "Wilayat al-Sham".[59]

Since mid-2018, IS has referred to its territory in the Levant simply as Wilayat al-Sham and has done the same with Iraq calling it Wilayat al-Iraq, but still continues to acknowledge and use references to specific regions in those territories, this has also been done with its claims in Yemen and Libya.[60]

As of 2022, the group seems to have increased its efforts in Syria compared to Iraq,[61] and has been reduced to several pockets in the Syrian desert, with local tribesmen acting as informants for the U.S. and other coalition forces. Despite this, the group managed to orchestrate a major prison break in January 2022.[17][62]

Afghanistan and Pakistan

[edit]

On 29 January 2015, Hafiz Saeed Khan, Abdul Rauf and other militants in the region swore an oath of allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Khan was subsequently named as the Wāli (Governor) of a new branch in Afghanistan and Pakistan called Khurasan Province, named after the historical Khorasan region.[63][64][65]

IS attempted to establish themselves in Southern Afghanistan, especially in Kandahar and Helmand provinces, but were resisted by Taliban forces.[66][67][68] They were able to establish a foothold in parts of Nangarhar, and recruited disaffected members of the Taliban.[69] In August 2015, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan leader, Usman Ghazi, swore allegiance to IS and announced that the group should be considered part of Wilayah Khorasan.[70]

The group suffered reversals in 2016, losing control of some territory in the wake of attacks from US Forces, the Afghan Government[71] and the Taliban.[72] Hafiz Saeed Khan was reportedly killed in a US drone strike in eastern Afghanistan on 25 July 2016.[73]

In 2019, the group announced a new Pakistan province (Wilayah Pakistan).[74] Despite this, as of 2022, the Khorasan province continues to operate in the country, also operating against neighboring Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, where some members have suggested that a Movarounnahr (or Transoxiana) province is established.[75] In July 2022, a Tajik-language magazine called Al-Azaim Tajiki was endorsed by the group, named after Yusuf al-Tajiki, a propagandist for the group killed by the Taliban.[76]

Since the Taliban's 2021 offensive, which ended with the takeover of Kabul and the end of the 20-year war in the country, IS-K have become a new focus for the group, with its funding and numbers increasing as a result of prison breaks of IS fighters during the offensive and subsequent recruiting.[17] Efforts have also increased to recruit fighters from neighboring Uzbekistan.[77]

Libya

[edit]

IS divides Libya into three historical provinces, claiming authority over Cyrenaica in the east, Fezzan in the desert south, and Tripolitania in the west, around the capital of Tripoli.[78][79]

In 2014, a number of leading IS commanders arrived in the city of Derna, which had been a major source of fighters in the Syrian civil war and Iraqi insurgency. Over a number of months, they united many local militant factions under their leadership and declared war on anyone who opposed them, killing judges, civic leaders, local militants who rejected their authority, and other opponents. On 5 October 2014, the militants, who by then controlled part of the city, gathered to pledge allegiance to the Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.[80][81] In February 2015, IS forces took over parts of the Libyan city of Sirte. In the following months, they used it as a base to capture neighbouring towns including Harawa,[82] and Nofaliya.[83] IS began governing Sirte and treating it as the capital of their territory.[84]

IS suffered reversals from mid-2015 when they were expelled from much of Derna following clashes with rival militants,[85] following months of intermittent fighting, IS eventually redeployed to other parts of Libya.[86] Its emir Abu Nabil al-Anbari was killed in a U.S. air strike in November 2015.[87] Libya's Interim Government launched a major offensive against IS territory around Sirte in May 2016,[88][89] capturing the city by December 2016.[90]

The group's current emir is Abu Bara al Sahrawi, who replaced Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi after his death in August 2021.[17]

Egypt

[edit]

The Egyptian militant group Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis swore allegiance to IS in November 2014. After al-Baghdadi's speech on 13 November, the group changed its name to Sinai Province on the Twitter feed claiming to represent the group.[47] The group has carried out attacks in Sinai.

On 1 July 2015, Wilayat Sinai launched a large-scale invasion on the Egyptian city of Sheikh Zuweid with more than 300 IS fighters and attacked more than 15 army and police positions using mortars, RPG's, light and heavy weapons in an attempt to capture the city.

On 29 February 2017, the group announced a new "Misr" province in Egypt in a propaganda video against Coptic Christians.[91]

In 2020, IS in Egypt occupied villages in Bir al-Abd town in North Sinai.

As of 2022, the group continues to attack local infrastructure, but has diminished due to persistent counterterrorism efforts by the Egyptian government and armed forces, who operate with the assistance of local tribesmen.[17][92]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]Al-Baghdadi announced a Wilayah in Saudi Arabia in November 2014, calling for the overthrow of the Saudi Royal Family and criticizing the Kingdom's participation in the US-led coalition against IS.[47] The group has carried out attacks in the country under the names of Najd Province and Hejaz Province.[93]

Yemen

[edit]IS established a Yemeni Wilayah in November 2014.[46][37] The branch's first attack occurred in March 2015, when it carried out suicide bombings on two Shia Mosques in the Yemeni capital.[94] At least eight IS Wilayat, named after existing provincial boundaries in Yemen, have claimed responsibility for attacks, including 'Adan Abyan Province, Al-Bayda Province, Hadramawt Province, Shabwah Province and Sana'a Province.[48] Following the outbreak of the Yemeni Civil War in 2015, IS struggled to establish much of a presence in the country in the face of competition from the larger and more established Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) militant group. Many of IS's regional cells in Yemen have not been visibly active since their establishment and the group has not been able to seize control of territory the way they have done in Iraq and Syria.[95] The group has also experienced leadership turmoil and defections from its rank and file.[96]

As of 2022, the group serves a key financial intermediary between Somalia and Khorasan provinces.[17]

Algeria

[edit]Members of a militant group named Jund al-Khilafah swore allegiance to IS in September 2014.[97] IS in Algeria gained notoriety when it beheaded French tourist Hervé Gourdel in September 2014.[37] On 13 November 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced that the group had changed its name to "Wilayah al-Jazair" in accordance to the structure of the rest of groups aligned with IS.[46][47] Algerian security forces killed the group's leader, Khalid Abu-Sulayman, in December 2014, and five of its six commanders in a May 2015 raid. Since then, the group has not claimed any significant attacks and has largely been silent.[98]

Nigeria and West Africa

[edit]

On 7 March 2015, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau pledged allegiance to IS via an audio message posted on the organisation's Twitter account.[99][100] Abu Mohammad al-Adnani welcomed the pledge of allegiance, and described it as an expansion of the group's caliphate to West Africa.[101] IS publications from late March 2015 began referring to members of Boko Haram as part of Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyyah (Islamic State's West Africa Province).[48] Boko Haram suffered significant reversals in the year following the pledge of allegiance, with an offensive by the Nigerian military, assisted by neighboring powers, driving them from much of the territory they had seized in North East Nigeria.[102] Boko Haram suffered a split in 2016, with IS appointing 'Abu Musab al-Barnawi' as the group's new leader, due to disagreements with Abubakar Shekau's leadership. This was rejected by Shekau and his supporters, who continued to operate independently.[103][104]

On 24 January 2022, the small town of Gudumbali was captured and declared as the province's capital. However, it was recaptured by Nigerian troops on 26 January.[105]

In the summer of 2022, ISWAP made several territorial gains in Nigeria.[106]

As of September 2022, the group continues to maintain its stronghold in northeastern Nigeria, and has again integrated or eclipsed its former competitor Boko Haram, as several fighters have rejoined the group. The group also orchestrated a prison break in July, near Abuja.[17]

In October 2022, the town of Ansongo was captured by IS's Sahel province.[107]

North Caucasus

[edit]IS militants in Syria issued a threat to Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2014: "we will liberate Chechnya and the entire Caucasus, God willing. Your throne has already teetered, it is under threat and will fall when we come to you because Allah is truly on our side."[108] In early 2015, commanders of the militant Caucasus Emirate group in Chechnya and Dagestan announced their defection and pledge of allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.[109][110] In a June 2015 audio statement posted online, IS spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani accepted the pledges of allegiance and appointed Abu Muhammad al-Qadari (Rustam Asildarov) as Governor of a new Caucasus Province. He called on other militants in the region to join with and follow al-Qadari.[49][111] The group has carried out occasional, low-level attacks since then.[112] Russian security services killed Rustam Asildarov in December 2016.[113]

Gaza

[edit]In February 2014, the Mujahideen Shura Council in the Environs of Jerusalem declared its support for IS.[114] On 2 April 2015, elements of this group, along with members of the Army of Islam and the Gaza faction of Ansar Bait al-Maqdis,[115][116] formed the Sheikh Omar Hadid Brigade, also known as Islamic State in Gaza,[117] as it predominantly operates in the Gaza Strip.

Somalia

[edit]The Islamic State in Somalia (ISS) has been active since 2015, and though it remains a small militia of around 300 fighters, it has been considered possible by experts that ISS controls a number of villages in Puntland's hinterland.[118] Furthermore, the group managed to capture and hold the town of Qandala for over a month in late 2016. At first, ISS did not receive official recognition by the Islamic State,[119] however, this was subsequently granted by December 2017.[120]

As of 2022, the group serves as an intermediary for IS provinces in Africa and the leadership based in Syria and Iraq. It also finances ISKP via Yemen.[17]

Sahel region

[edit]

The Islamic State – Sahel Province was formed on 15 May 2015 as the result of a split within the militant group Al-Mourabitoun. The rift was a reaction to the adherence of one of its leaders, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui,[121] to the Islamic State. From March 2019 to 2022, IS-GS was formally part of the Islamic State – West Africa Province (ISWAP);[122] when it was also called "ISWAP-Greater Sahara".[123] In March 2022, IS declared the province autonomous, separating it from its West Africa Province[17] and naming it Islamic State – Sahel Province (ISSP) the group would go on to takeover large swathes of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Between 2022 and 2023, the group saw major gains in the Mali War, occupying large swarths of territory in southeastern Mali. Tidermène was captured by the group on 12 April 2023.[124]

East Asia

[edit]

Abu Sayyaf is IS's most powerful affiliate in the Philippines; another IS-affiliated group is the Maute group. Both groups worked together with other IS affiliates to seize parts of Marawi City on 23 May 2017, starting the Battle of Marawi.[125]

On 16 October, IS's Emir of Southeast Asia Isnilon Hapilon, along with the Maute group's remaining leader Omar Maute was killed by the Armed Forces of the Philippines. Previously, the Maute group's co-leader and Omar's brother Abdullah Maute, as well as their other five male siblings, had been neutralized by the ongoing counter-offensives. Two days after the leaders' death, the Armed Forces of the Philippines said Malaysian terrorist and senior commander Mahmud Ahmad is also presumed killed in another operation.

The Battle of Marawi was declared over by 23 October by the government, at which point all participating militants have been successfully neutralized, effectively blocking IS's Asian expansion. The government wiped out the Maute group after the battle.

In December 2017, remnants of the Maute group started recruiting new members to form a new group called "Turaifie Group" whose leader, Abu Turaifie, claimed himself to be a successor of former leader Abu Sayyaf Isnilon Hapilon.[126]

As of 2022, only pockets in Indonesia and the Philippines remain, and major attacks have decreased as a result of successful counterterrorism efforts by the governments of both states.[17]

During 2023, IS witnessed a major resurgence in the Philippines (especially from August), with the group claiming more attacks in the country than during the previous 2 years combined, including several significant attacks such as the Mindanao State University bombing in Marawi.[127][128]

On 22 March 2024, the Philippines announced that Abu Sayyaf had been "fully dismantled", bringing an end to the decades-long jihadist insurgency.[129]

According to the Islamic State Al-Naba newspaper, the group continued to conduct attacks on the Philippine Government and Army and the Moro militias until 11 April, which is yet to be confirmed by official Philippine Government sources.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]In October 2017, a video emerged on pro-IS channels that showed a small number of militants in the Democratic Republic of the Congo who declared to be part of the "City of Monotheism and Monotheists" (MTM) group. The leader of the group went on to say that "this is Dar al-Islam of the Islamic State in Central Africa" and called upon other like-minded individuals to travel to MTM territory in order to join the war against the government. The Long War Journal noted that though this pro-IS group in Congo appeared to be very small, its emergence had gained a notable amount of attention from IS sympathizers.[130] On 24 July 2019, a video was released referring to IS's presence in the country as the Central African Wilayat showing fighters pledging allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.[131]

As of 2022, the group has doubled its territory and increased its numbers as a result of orchestrated prison breaks, with 2,000 prisoners freed since 2020.[17]

Mozambique

[edit]After taking control of the Mozambican town of Mocímboa da Praia during an offensive in August 2020, local IS insurgents declared it the capital of their province. The militants consequently expanded further by capturing several islands in the Indian Ocean, with Vamizi Island being the most prominent.[132]

In May 2022, the province was separated from Central Africa Province and became known as the Mozambique Province (ISM).[17]

India

[edit]The Islamic State operated in India and the Kashmir region through its Islamic State Jammu & Kashmir (ISJK) branch, which had begun in February 2016.[133] The Islamic State – Khorasan Province declared Wilayah [Wilayat] al-Hind (India Province) for IS on 11 May 2019 after clashes in Jammu and Kashmir in which ISJK leader Ishfaq Ahmad Sofi was killed.[134]

Shafi Armar, a former member of the Indian Mujahideen, was formerly the chief of operations for the IS in India.[135] He and his brother Sultan Armar founded the Indian IS affiliates Ansar-ut Tawhid fi Bilad al-Hind (transl. Supporters of Monotheism in the Land of India) and Janood-ul-Khalifa-e-Hind (transl. Caliph's Army of India).[136][137] Both he and his brother were killed in action during Syrian Civil War in 2015, which was only confirmed in 2019 because his online account was controlled by other militants in the group which added to the confusion.[138] Janood-ul-Khalifa-e-Hind has published the pro-IS propaganda magazine Sawt al-Hind (transl. Voice of India) since February 2020.[139]

On 20 March 2024, the special forces arrested the IS India chief, Haris Farooqi and one of his associates while they were trying to cross to India from neighbouring Bangladesh. Police explained that the suspects had planned many sabotage activities and IED attacks inside India.[140]

Bangladesh

[edit]Islamic State – Bengal Province (Wilayat al-Bengal) is the province of IS in Bangladesh, it operates through the group Islamic State Bangladesh (ISB) and has claimed attacks in the country since October 2015. Neo-Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh, an offshoot of Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh, also operates as its branch.[141][142]

The first emir of Wilayat al-Bengal, Abu Ibrahim al-Hanif, is believed to be Mohammad Saifullah Ozaki (born as Sajit Chandra Debnath, 1982) a Bangladeshi Japanese economist who went to Syria in 2015 and joined IS. A Hindu convert to Islam, he reportedly lead the 2016 Dhaka attack. He was detained in Iraq in 2019 and Abu Muhammed al-Bengali was announced as the new emir of the province.[143][142]

Azerbaijan

[edit]On 2 July 2019, as part of a series of videos showing supporters and fighters of IS around the world renewing their pledge of allegiance to IS, a video was published from Azerbaijan featuring three fighters armed with Kalashnikov style rifles pledging their allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The video was formally released by IS.[144]

4 months later, after al-Baghdadi's death on 27 October 2019, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi received pledges of allegiance (bayah) from various provinces and regions, with photos of fighters from Azerbaijan pledging allegiance to him, on 29 November.[145]

On 19 September, 2024, the Islamic State claimed its first-ever attack in Azerbaijan, via its weekly Al-Naba newsletter, claiming to have killed 7 Azeri security personnel and wounded 1 in a clash in Qusar district, northern Azerbaijan, five days prior.[146]

Turkey

[edit]Wilayat Turkiya was formally declared in July 2019 when a video was published by IS featuring Turkish jihadists giving their bay'ah to the group's leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Reference was also made to the Wilayat prior to its formal introduction, in April 2019 in a video featuring the group's leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in his second ever video appearance, and first appearance in five years, he was seen holding dossiers from various Wilayats the group claims one of which was labeled as Wilayat Turkey, which was the first known such usage as a reference to the Turkish Wilayat.[147][148][149]

Administrative organization

[edit]Provinces

[edit]The Islamic State's main base of operations was in their territory of Ar-Raqqah in Syria, until 2017, where it was recaptured by the Syrian Democratic Forces. From there, orders were given to affiliate groups, called wilayat, spread across the Levant, Asia and Africa. Few of these wilayat have declared their capital cities, with the exception of al-Sham with Ar-Raqqah,[1] al-Iraq with Mosul, and Central Africa with Mocímboa da Praia.[150] It also had claims on the entirety of the Muslim world, including Central Asia, the former Ottoman Balkans, South East Asia, and the northern part of Africa.[151][152] Other times, however, it expressed also a desire for world domination, with labels on certain areas of the old world as well as the new world.[153][154]

Ministries

[edit]In addition to its territorial administration, the group also established dāwāwīn (ministries) for the political administration of the quasi-state under al-Baghdadi's administration,[168][169][170] modelled after Abu Ayyub al-Masri's infrastructure for the Islamic State of Iraq.[171]

| Dīwān / Ministry | Date of creation | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Education and Teaching[h] Diwan al-Tarbiyya wa al-Ta’lim |

July 2014 | Responsible for education in a regular and extremist context.[172] Its first minister was Reda Seyam. |

| Services Diwan al-Khidamat |

June 2014 | Responsible for the administration of public spaces, such as parks and roads. One example of the latter was the construction of "Caliphate Way", a highway built in the industrial area of Mosul, which reduced congestion in the area.[173] |

| Rikaz[i] Diwan al-Rikaz |

? | Responsible for handling and exploitation of profitable resources. Its two known divisions handle fossil fuels (e.g. petroleum) and antiquities. |

| Da'wah and Masajid (and Awqaf) Diwan al-Da’wah wa al-Masajid (wa al-Awqaf) |

? | Responsible for Dawah and mosque and religious staff administration. |

| Health Diwan al-Sihha |

June 2014 | Responsible for health services and hospitals. An "Islamic State Health Service" was established in 2015, featuring a logo modelled after the one used by the British National Health Service.[174] All medical schools served under this ministry rather than the Ministry of Education. |

| Tribal Relations Diwan al-Asha'ir |

? | Responsible for dealing with nomadic tribes in the core region of IS. While the group committed atrocities against tribes such as Al-Shaitat and documents obtained after the group's loss of territory reflect a harsh tone against the nomadic groups, other documents show organized deliveries of supplies to the same groups. This dīwān was also known as an Office. |

| Diwan al-Amn (Islamic State Intelligence) | ? | Responsible for public security and anti-espionage operations. |

| Zakah Diwan al-Zakah |

June 2014 | Responsible for the collection and distribution of the Zakah. |

| Treasury Diwan Bayt al-mal |

? | Responsible for the finances of the group and the dinar. Its Diwan al-Musadara is responsible for expropriations and is based on medieval Islam.[175] |

| Hisbah Diwan al-Hisbah |

? | The Hisbah (religious police) served this ministry, being in charge of enforcing the group's version of Islamic jurisprudence (sharia law) in public. |

| Judgement and Grievances Diwan al-Qada wa al-Mazalim |

? | Responsible for enforcing and clarifying judicial matters (e.g. Islamic court) and family and marriage-related issues. Also based in medieval Islam.[clarification needed] |

| Public Relations Diwan al-Alaqat al-Amma |

? | Public relations (PR) department. |

| Agriculture Diwan al-Zira'a |

June 2014 | Responsible for the regulation of agriculture and livestock. A RAND study revealed that harvests in IS territory were relatively normal, with commercial vehicle traffic increasing under the new administration. Only with the loss of territory and access to resources such as electricity did harvests begin to decay around 2016.[176] |

| Fatwa and Investigation Diwan al-Ifta' wa al-Buhuth |

? | Responsible for issuing and clarifying fatwas. It also wrote and published text media used in training camps through its publishing body Maktabat al-Himma. |

| Soldiery Diwan al-Jund |

? | Responsible for the Army of the Islamic State and its management, training and distribution. It is sometimes referred to as the "Soldiers Department".[175] |

| Media[j] Diwan al-I'lam al-Markazi[177] |

? | Responsible for the publishing bodies of IS, such as AlHayat Media Center, al-Furqan Media Foundation, Al-Bayan radio, Ajnad Foundation, Al-Naba, and Maktabat al-Himma. It is also in charge of the publication of magazines Dabiq, Dar al-Islam, Konstantiniyye, Istok, and later on Rumiyah. Additionally, it's the ministry in charge of translations. |

| Fay' and Ghana'im[k] Diwan al-Fay' wa al-Ghana'im |

? | Responsible for administering and distributing war spoils that come from battles. |

| Real Estate Diwan al-'Aqarat wa al-Kharaj |

? | Responsible for real estate seized from non-Muslims or abandoned by its original owners in order to accommodate regular and new fighters or civilians.[178] |

Regional administrative offices

[edit]This section contains a list that has not been properly sorted. See MOS:LISTSORT for more information. (March 2023) |

Islamic State had created various regional offices during the period (2017–2019) to organize & direct its human and other resources & reviving its external operational capability.[179][180][181]

The “most vigorous and best-established” of IS's offices set up at the centre to oversee the wilayats are:

Al-Siddiq office in Afghanistan, which “covers South Asia and, according to some UN Member States, Central Asia”;

Al-Karrar office in Somalia, which also covers Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); and

Al-Furqan office in the Lake Chad basin, where the borders of Niger, Chad, Cameroon, and Nigeria converge. The Furqan office covers these states in North Africa and the broader western Sahel, overseeing ISGS/ISSP.

IS's other “three regional offices are low-functioning or moribund”, says the Monitoring Team, and these are:

Al-Anfal office in Libya, which covered “parts of northern Africa and the Sahel”;

The Umm al-Qura office “based in Yemen and … responsible for the Arabian Peninsula”; and

The Zu al-Nurayn office in the Sinai Peninsula “responsible for Egypt and the Sudan”.[179][182][181][180]

Society

[edit]The territories in Iraq and Syria, which was occupied by the Islamic State and claimed as part of its self-dubbed "Caliphate"[183] saw the creation of one of the most criminally active, totalitarian corrupt and violent regimes in modern times, and it ruled that territory until its defeat in 2019.[184] IS murdered tens of thousands of civilians,[185] kidnapped several thousand people, and forced hundreds of thousands of others to flee. It systematically committed torture, mass rapes, forced marriages,[186] extreme acts of ethnic cleansing, mass murder, genocide, robbery, extortion, smuggling, slavery, kidnappings, and the use of child soldiers; in its implementation of strict interpretations of Sharia law which were based on ancient eighth-century methods, they carried out public "punishments"[187] such as beheadings, crucifixions, beatings, mutilation and dismemberment, the stoning of both children and adults, and the live burning of people. IS members committed rape against tens of thousands of girls and women (mainly members of non-Sunni minority groups and families).

On 29 May, IS raided a village in Syria and at least 15 civilians were killed, including, according to Human Rights Watch, at least six children.[188] A hospital in the area confirmed that it had received 15 bodies on the same day.[189] The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that on 1 June, a 102-year-old man was killed along with his whole family in a village in Hama province.[190] According to Reuters, 1,878 people were killed in Syria by IS during the last six months of 2014, most of them civilians.[191]

During its occupation of Mosul, IS implemented a sharia school curriculum which banned the teaching of art, music, national history, literature and Christianity. Although Charles Darwin's theory of evolution has never been taught in Iraqi schools, that subject was also banned from the school curriculum. Patriotic songs were declared blasphemous, and orders were given to remove certain pictures from school textbooks.[192][193][194][195] Iraqi parents largely boycotted schools in which the new curriculum was introduced.[196]

After capturing cities in Iraq, IS issued guidelines on how to wear clothes and veils. IS warned women in the city of Mosul to wear full-face veils or face severe punishment.[197] A cleric told Reuters in Mosul that IS gunmen had ordered him to read out the warning in his mosque when worshippers gathered. IS ordered the faces of both male and female mannequins to be covered, in an order which also banned the use of naked mannequins.[198] In Raqqa the group used its two battalions of female fighters in the city to enforce compliance by women with its strict laws on individual conduct.[199]

IS released 16 notes labelled "Contract of the City", a set of rules aimed at civilians in Nineveh. One rule stipulated that women should stay at home and not go outside unless necessary. Another rule said that stealing would be punished by amputation.[200][201] In addition to banning the sale and use of alcohol, IS banned the sale and use of cigarettes and hookah pipes. It also banned "music and songs in cars, at parties, in shops and in public, as well as photographs of people in shop windows".[202]

According to The Economist, the group also adopted certain practices seen in Saudi Arabia, including the establishment of religious police to root out "vice" and enforce attendance at daily prayers, the widespread use of capital punishment, and the destruction of Christian churches and non-Sunni mosques or their conversion to other uses.[203]

IS carried out executions on both men and women who were accused of various acts and found guilty of crimes against Islam such as sodomy,[204] adultery, usage and possession of contraband, rape, blasphemy, witchcraft,[205] renouncing Islam and murder. Before the accused were executed, their charges were read to them and the spectators. Executions take various forms, including stoning to death, crucifixions, beheadings, burning people alive, and throwing people from tall buildings.[206][207][208][209] The Islamic State in Iraq frequently carried out mass executions in Mosul and Hawija.

Terror

[edit]The condition of human rights in the territory controlled by the Islamic State is considered to be among the worst in the world.[210][211][212][213] In the areas they controlled the Islamic State would commit several genocides against local ethnic groups between 2014 and 2017.[214][215][216] The Yazidi genocide was characterized by massacres, genocidal rape, and forced conversions to Islam. The Yazidis are a Kurdish-speaking people[217] who are indigenous to Kurdistan who practice Yazidism, a monotheistic Iranian ethnoreligion derived from the Indo-Iranian tradition.[218] the Iraqi Turkmen genocide began when ISIS captured Iraqi Turkmen lands in 2014 and it continued until ISIS lost all of their land in Iraq. In 2017, ISIS's persecution of Iraqi Turkmen was officially recognized as a genocide by the Parliament of Iraq,[219][220] and in 2018, the sexual slavery of Iraqi Turkmen girls and women was recognized by the United Nations.[221][222]

The Islamic State would persecute Christians in its territory in ways which involves the systematic mass murder[223][224][225] Persecution of Christian minorities climaxed following the Syrian civil war and later by its spillover but has since intensified further.[226][227][18] Christians have been subjected to massacres, forced conversions, rape, sexual slavery, and the systematic destruction of their historical sites, churches and other places of worship.

The depopulation of Christians from the Middle East by the Islamic State as well as other organisations and governments has been formally recognised as an ongoing genocide by the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom. Christians remain the most persecuted religious group in the Middle East, and Christians in Iraq are “close to extinction”.[228][229][230] According to estimates by the US State Department, the number of Christians in Iraq has fallen from 1.2 million 2011 to 120,000 in 2024, and the number in Syria from 1.5 million to 300,000, falls driven by persecution by Islamic terrorists.[18]

Shia Muslims were also persecuted, since 2014. Persecutions have taken place in Iraq, Syria, and other parts of the world.

Shia Muslims have been killed and otherwise persecuted by IS. On 12 June 2014, the Islamic State killed 1,700 unarmed Shia Iraqi Army cadet recruits in the Camp Speicher massacre.[231][232][233] IS has also targeted Shia prisoners.[234] According to witnesses, after the militant group took the city of Mosul, they divided the Sunni prisoners from the Shia prisoners.[234] Up to 670[235] Shia prisoners were then taken to another location and executed.[234] Kurdish officials in Erbil reported on the incident of Sunni and Shia prisoners being separated and Shia prisoners being killed after the Mosul prison fell to IS.[234]

In a special report released on 2 September 2014, Amnesty International described how IS had "systematically targeted non-Sunni Muslim communities, killing or abducting hundreds, possibly thousands, of individuals and forcing more than tens of thousands of Shias, Sunnis, along with other minorities to flee the areas it has captured since 10 June 2014". The most targeted Shia groups in Nineveh Governorate were Shia Turkmens and Shabaks.[114]

Destruction of Cultural Heritage

[edit]

Since 2014, the Islamic State has destroyed cultural heritage on an unprecedented scale, primarily in Iraq and Syria, but also in Libya. These attacks and demolitions targeted a variety of ancient and medieval artifacts, museums, libraries, and places of worship, among other sites of importance to human history. Between June 2014 and February 2015, the Islamic State's Salafi jihadists plundered and destroyed at least 28 historic religious buildings in Mosul alone, with the most notable event being the 2014 destruction of Mosul Museum artifacts.[236] Many of the valuables that were looted during these demolitions were used to bolster the economy of the Islamic State.[236]

Along with antique Mesopotamian sites of significance, the Islamic State inflicted particularly cataclysmic levels of damage upon Iraqi Christian heritage. It also destroyed Islamic sites that it declared to be in contradiction of that which is permissible in the Islamic State ideology, thus culminating in the destruction of Shia Islamic sites and non-compliant Sunni Islamic sites.

See also

[edit]- Early Muslim conquests

- Boko Haram

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (1996–2001)

- Islamic Emirate of Yemen

- Islamic Emirate of Kunar

- Islamic Emirate of Badakhshan

- Islamic Emirate of Rafah

- Islamic Emirate of Kurdistan

- Caucasus Emirate

- Syrian Salvation Government

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- First Islamic State

Notes

[edit]- ^ In October 2015, a film was released showing how the Gold Dinar would be introduced as the sole official currency of the proto-state. De facto, however, it saw limited circulation. In the areas where it saw circulation, it was forbidden to use other currencies with the exception of the dollar. Other areas saw the use of different types of currencies such as the Syrian pound and the Iraqi dinar.[15]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Some provinces existed only de jure as the Islamic State did not exercise control over these territories

- ^ Includes the Russian North Caucasus (mainly Islamic areas such as Dagestan or Chechnya), as well as Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.[155]

- ^ A faction known as the "Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda" was set up in April 2016, but was only active in Somalia as well as Kenya for a short time.

- ^ a b c d Since mid-2018, IS has referred to its territory in the Levant simply as Wilayat al-Sham and has done the same with Iraq calling it Wilayat al-Iraq, but still continues to acknowledge and use references to specific regions in those territories. This has also been done with its claims in Libya and Yemen.[60][162]

- ^ A Propaganda video under the name "Hunt Them Down, O Monotheists", used the name Wilayat al-Somal (Somalia Province).[120] Since then, however, the new name has not been consistently applied to the group by pro-IS media.[167]

- ^ The Islamic State controlled some territory outside of its wilayat under the Khalid ibn al-Walid Army until 2018, which administered its territory from Al-Shajara.

- ^ Also known as the Diwan of Education or the Diwan of Education and Teaching of Islamic State.

- ^ Another official name is the Diwan of Resources, and it is also known as the Diwan of Natural Resources or the Diwan of Precious Resources.

- ^ Also known as the Diwan of Central Media or Ministry of Information (Arabic: وزارة الإعلام).

- ^ Literally the Diwan of Spoils and Plunder.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Rasheed (2015), p. 3.

- ^ Zelin (2016), p. 4.

- ^ Nico Prucha (1 August 2017). "Part 2: "Upon the prophetic methodology" and the media universe". Online Jihad: Monitoring Jihadist Online Communities. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Marshall, Alex (9 November 2014). "How Isis got its anthem". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (28 August 2017). "Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents (cont.- IV)". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (17 September 2016). "Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents (continued...again)". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (11 January 2016). "Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents (cont.)". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (27 January 2015). "Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi's Blog. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Rukmini Callimachi, Ivor Prickett (4 April 2018). "The ISIS Files". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Rukmini Callimachi, Andrew Rossback (4 April 2018). "The ISIS Files: Extreme Brutality and Detailed Record-Keeping". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Tomlinson, Lucas (21 April 2017). "ISIS moves its capital in Syria". Fox News. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Aboufadel, Leith (3 December 2018). "Breaking: US-backed forces allegedly enter Daesh's new capital". al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Shinkman, Paul D. (27 December 2017). "ISIS By the Numbers in 2017". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jones, Seth G.; Dobbins, James; Byman, Daniel; et al. (2017). "Rolling Back the Islamic State". RAND Corporation. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "ISIS introduces 'Golden Dinar' currency, Hopes it will collapse U.S. dollar". The Foreign Desk. 6 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Shelly Kittleson (31 December 2017). "Iraqi forces hunt down IS remnants in Hamrin Mountains". al-Monitor. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chesnutt, Kate; Zimmerman, Katherine (8 September 2022). "The State of al Qaeda and ISIS Around the World". Critical Threats. Cite error: The named reference "Chesnutt 2022" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d "UN experts say Islamic State group almost doubled the territory they control in Mali in under a year". AP News. 26 August 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Eklund, Lina; Degerald, Michael; Brandt, Martin; Prishchepov, Alexander V; Pilesjö, Petter (28 April 2017). "How conflict affects land use: agricultural activity in areas seized by the Islamic State". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (5): 054004. Bibcode:2017ERL....12e4004E. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa673a.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini [@rcallimachi] (17 October 2017). "4. In an email, US-backed Coalition fighting ISIS told me that of the 104,000 square km the group held in Iraq/Syria, 93,790 is liberated" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Although they have been besieged by Russia, Iran, and the regime for two years, thousands of ISIS members are still within an area of 4000 km² without any intention to launch a military operation against them • The Syrian Observatory For Human Rights". 20 February 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Trump says all Islamic State land lost in Syria, SDF says fight continues | Reuters". 24 March 2019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Trump's maps of the 'caliphate' disregard ISIS pockets near Syrian gov't areas". Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Complete map update of Syrian War – End of February 2019". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Syrian army attacks Islamic State targets in desert: report". Reuters. 5 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2023 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Al-Yaqeen Media. "Three Years on the Islamic State". Digital image, 11 June 2017. https://i.redd.it/i2id92mph33z.jpg

- ^ Trauthig 2020, pp. 13, 18.

- ^ "IS Down But Still a Threat in Many Countries". Voice of America. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Kunle Adebajo (21 May 2021). "How Did Abubakar Shekau Die? Here's What We Know So Far". Humangle. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Dulue Mbachu (17 June 2021). "Death of Boko Haram leader doesn't end northeast Nigeria's humanitarian crisis". The New Humanitarian. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b Romain Caillet (December 2014). "ISIS'S GLOBAL MESSAGING STRATEGY FACT SHEET" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Johnson, M. Alex (3 September 2014). "'Deviant and Pathological': What Do ISIS Extremists Really Want?". NBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ Tran, Mark; Weaver, Matthew (30 June 2014). "Isis announces Islamic caliphate in area straddling Iraq and Syria". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ McGrath, Timothy (2 July 2014). "Watch this English-speaking ISIS fighter explain how a 98-year-old colonial map created today's conflict". Los Angeles Times. GlobalPost. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Romain Caillet (27 December 2013). "The Islamic State: Leaving al-Qaeda Behind". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (17 November 2014). "Analysis: Islamic State snuff videos help to attract more followers". Long War Journal. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Islamic State builds on al-Qaeda lands". BBC News. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ "The Islamic State's Archipelago of Provinces". Washington Institute for Near East Policy. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ^ "Islamic State in Somalia claims capture of port town". The Long War Journal. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "How Bangladesh Became Fertile Ground for al-Qa'ida and the Islamic State". CTC Sentinel. 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "The Islamic State grows in the Philippines". The Long War Journal. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Has the Islamic State Abandoned Its Provincial Model in the Philippines?". 22 July 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Piazza, James A.; Soules, Michael J. (2021). "Terror after the Caliphate: The Effect of ISIS Loss of Control over Population Centers on Patterns of Global Terrorism". Security Studies. 30: 107–135. doi:10.1080/09636412.2021.1885729. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 232411590.

- ^ "ISIS Governance in Syria." (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ a b The ISIS Threat: The Rise of the Islamic State and their Dangerous Potential. United States Congress. 2015. ISBN 9781505837636.

- ^ a b c d "The Islamic State's model". The Washington Post. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Islamic State leader urges attacks in Saudi Arabia: speech". Reuters. 13 November 2014.

We announce to you the expansion of the Islamic State to new countries, to the countries of the Haramayn, Yemen, Egypt, Libya [and] Algeria

- ^ a b c d "ISIS Global Intelligence Summary March 1 – May 7, 2015" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War. 10 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b "ISIS Declares Governorate in Russia's North Caucasus Region". Institute for the Study of War. 23 June 2015.

- ^ "داعش الساحل" يعلن مبايعة القرشي زعيما جديدا". Al-Ain (in Arabic). 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Chechen IS Militants In Kobani Vow To Save Kurds From Communism". www.rferl.org. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Fairfield, Hannah; Wallace, Tim; Watkins, Derek (21 May 2015). "How ISIS Expands". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "The Rump Islamic Emirate of Iraq". The Long War Journal. 16 October 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "ISIS' 'Southern Division' praises foreign suicide bombers". The Long War Journal. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية يعلن قيام "ولاية الفرات" على أراض سورية وعراقية". France 24 (in Arabic). 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (10 September 2014). "Islamic State "Euphrates Province" Statement: Translation and Analysis". aymennjawad.org. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "The Islamic State" (PDF). The Soufan Group. 28 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State Announces Creation of Second New Province in Northern Iraq". SITE Intelligence Group. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ @Terror_Monitor (21 July 2018). "#SYRIA #IslamicState Claims Killing/Wounding Dozens Of #SAA Soldiers in Repelling An Attempted Advance in the Countryside Of #Daraa. #TerrorMonitor" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad (26 September 2018). "Islamic State Shifts From Provinces and Governance to Global Insurgency". Global Observatory. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Merchant, Nomaan (15 September 2022). "US Intelligence Predicted Resurgence of Islamic State Group Threat, Declassified Report Shows". Military.com.

- ^ Al-Khalidi, Suleiman (13 September 2022). "Tribal spies in Syria help U.S. win drone war against Islamic State". Reuters.

- ^ a b "IS announces expansion into AfPak, parts of India". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Pakistani Taliban emir for Bajaur joins Islamic State". The Long War Journal. 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan drone strike 'kills IS commander Abdul Rauf'". BBC News.

- ^ "ISIS reportedly moves into Afghanistan, is even fighting Taliban". 12 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "ISIS, Taliban announced Jihad against each other". The Khaama Press News Agency. 20 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Taliban leader: allegiance to ISIS 'haram'". Rudaw. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Lynne O'Donnell (8 September 2015). "Islamic State group loyalists eye a presence in Afghanistan". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "IMU Declares It Is Now Part of the Islamic State". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ "Air strikes hit Islamic State in Afghanistan under new rules: U.S." Reuters. 14 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Taliban Captures IS Bases in Afghanistan". Voice of America. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "IS leader in Afghanistan killed, US believes". BBC News. 12 August 2016.

- ^ "Islamic State Announces 'Pakistan Province'". VOA News. 16 May 2019.

- ^ Webber, Lucas; Valle, Riccardo (6 August 2022). "Islamic State Khorasan's Expanded Vision in South and Central Asia". The Diplomat.

- ^ Alkhouri, Laith; Webber, Lucas (20 July 2022). "Islamic State launches new Tajik propaganda network". Eurasianet.

- ^ Webber, Lucas; Alkhouri, Laith (29 August 2022). "Islamic State recruiting Uzbeks to fight in Afghanistan". Eurasianet.

- ^ a b "Islamic State Sprouting Limbs Beyond Its Base". The New York Times. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "ISIS atrocity in Libya demonstrates its growing reach in North Africa". CNN. 17 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Libyan city is first outside Syria, Iraq to join ISIS". Haaretz.com. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Islamic State of Libya Isn't Much of a State". Foreign Policy. 17 February 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ Hassan Morajea (6 June 2015). "Libyan gains may offer ISIS a base for new attacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ "IS said to have taken another Libyan town". Times of Malta. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "The Islamic State's Burgeoning Capital in Sirte, Libya". Washington Institute of Near East Policy. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Libya officials: Jihadis driving IS from eastern stronghold". Associated Press. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State in retreat around east Libyan city: military". Reuters. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Martin Pengelly (14 November 2015). "Islamic State leader in Libya 'killed in US airstrike'". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Libyan security forces pushing Islamic State back from vicinity of oil terminals". Reuters. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Libyan brigades capture air base from Islamic State south of Sirte: spokesman". Reuters. 4 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Libyan forces clear last Islamic State hold-out in Sirte". Reuters. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "#Egypt: #ISIS 'Misr' released video "And fight the polytheists collectively.." focusing primarily on Egypt's #Coptic Christians". 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Egypt army makes gains against Islamic State in western Sinai". Al-Monitor. 22 August 2022.

- ^ al-Shihri, Abdullah (7 August 2015). "Saudi Arabia mosque bombing that killed 15 claimed by 'new' Islamic State group". The Age. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Yemen crisis: Islamic State claims Sanaa mosque attacks". BBC News. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "ISIS Fails to Gain Much Traction in Yemen". The Wall Street Journal. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ "More Islamic State members reject governor of Yemen Province". Long War Journal. 28 December 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Fadel, Leila (18 November 2014). "With Cash And Cachet, The Islamic State Expands Its Empire". NPR.

- ^ "If at First You Don't Succeed, Try Deception: The Islamic State's Expansion Efforts in Algeria". Jamestown Foundation. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria's Boko Haram pledges allegiance to Islamic State". BBC News. 7 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Adam Chandler (9 March 2015). "The Islamic State of Boko Haram? :The terrorist group has pledged its allegiance to ISIS. But what does that really mean?". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b "IS welcomes Boko Haram allegiance: tape". AFP. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Boko Haram's Buyer's Remorse". Foreign Policy Magazine. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Boko Haram in Nigeria: Abu Musab al-Barnawi named as new leader". BBC News. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ "Behind Boko Haram's Split: A Leader Too Radical for Islamic State". The Wall Street Journal. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ Maina, Maina (26 January 2022). "Troops battle ISWAP in Borno, dislodge caliphate HQ, recover Gudumbali". Daily Post.

- ^ "ISWAP Still Controls Vast Areas of Guzamala in Northeast". 30 June 2022.

- ^ Diallo, Tiemoko (14 October 2022). "Islamist militants in Mali kill hundreds, displace thousands in eastern advance". Reuters.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (6 September 2014). "Islamic State militants want to fight Putin". The Washington Post.

- ^ "What Caused the Demise of the Caucasus Emirate?". Jamestown. Jamestown Foundation. 18 June 2015.

- ^ "Caucasus Emirate and Islamic State Split Slows Militant Activities in North Caucasus". Jamestown. Jamestown Foundation. 13 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Two North Caucasus Rebel Leaders Face Off in Islamic State–Caucasus Emirate Dispute". Jamestown. The Jamestown Foundation. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "IS's North Caucasus Affiliate Calls For Recruits To Join It in Daghestan". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Russian security service says killed North Caucasus Islamic State 'emir'". AFP. 4 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ a b al-Ghoul, Asmaa (27 February 2014). "Gaza Salafists pledge allegiance to ISIS". Al-Monitor. Gaza City, Gaza Strip. Retrieved 25 September 2014. Cite error: The named reference "auto" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Levy, Rachael (1 July 2014). "Egyptian group claims it killed the Three Israeli Teens". Vocative. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ BBC Monitoring (30 January 2015). "Egypt attack: Profile of Sinai Province militant group". BBC News. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Levy, Rachael (9 June 2014). "ISIS: We Are Operating in Gaza". Vocative. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Harun Maruf (9 June 2017). "Somali Officials Condemn Attacks, Vow Revenge". Voice of America. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Warner (2017), p. 30.

- ^ a b c Thomas Joscelyn; Caleb Weiss (27 December 2016). "Islamic State video promotes Somali arm, incites attacks during holidays". Long War Journal. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Rewards for ISIS-GS Leader Adnan Abu Walid". VOA. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Zenn (2020), p. 6.

- ^ Bacon & Warner (2021), p. 80.

- ^ BBC Africa Today: Islamic State Sahel Province fighters seize commune in Mali, BBC, 2023

- ^ Villamor, Felipe; Emont, Jon (20 July 2017). "ISIS' Core Helps Fund Militants in Philippines, Report Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Maute recruitment continues around Marawi – AFP". ABS-CBN Corporation. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "IS Claims Bombing at Catholic Mass in Philippines". SITE Intel Group.

- ^ "Weekly inSITE on the Islamic State for August 23-29, 2023". SITE Intel Group.

- ^ "Philippine General Says Abu Sayyaf Group is 'Dismantled' | Atlas News". 22 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Caleb Weiss (15 October 2017). "Islamic State-loyal group calls for people to join the jihad in the Congo". Long War Journal. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "New video message from The Islamic State: "And The [Best] Outcome Is for the Righteous – Wilāyat Wasaṭ Ifrīqīyyah"". jihadology.net. 24 July 2019.

- ^ "ISIS take over luxury islands popular among A-list celebrities". News.com.au. 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Islamic State Jammu & Kashmir – (Islamic State / ISJK / ISISJK)". Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium.

- ^ Islamic State claims province in India for first time after clash in Kashmir. Euronews.

- ^ "Shafi Armar: 26-year-old sought to set up ISIS module in every Indian state – Oneindia News". oneindia.com. 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Janood-ul-Khalifa-e-Hind / Army of Caliph of India (Islamic State India/ ISI / ISISI)". Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Ansar-ut Tawhid fi Bilad al-Hind (AuT)". Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Bhatkal's Armar brothers who ran the Indian Islamic State confirmed dead". Oneindia. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Taneja, Kabir (16 April 2020). "Islamic State propaganda in India". Observer Research Foundation.

- ^ "ISIS India Head, Key Aide Arrested In Major Op In Assam's Dhubri". NDTV. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Islamic State Bangladesh (ISB, ISISB) -- Abu Jandal al-Bangali". Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium.

- ^ a b IS names new emir in Bengal issues threat to carry out attacks in India and Bangladesh. Times of India.

- ^ "Ex-Ritsumeikan professor held in Iraq for terrorist recruitment". The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ a b c d "New video message from the Islamic State: "And the [Best] Outcome is for the Righteous – Azerbaijan"".

- ^ "The Islamic State's Bayat Campaign". jihadology.net. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "In First Recorded Fighting Activity in Azerbaijan, IS Reports Clash in Qusar District Inflicting 8 Casualties". SITE. 19 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Baghdadi is Back—and Vows the Islamic State Will be, Too". The New Yorker. 29 April 2019.

- ^ a b Islamic State Turkey province video claims new wilayah in old turf, Defense Post

- ^ a b "IS Decentralizing Into 'Provinces' in Bid to Return". VOA. 21 July 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "ISIS attacks surge in Africa even as Trump boasts of a '100-percent' defeated caliphate". The Washington Post. 18 October 2020.

- ^ "ISIS map of areas it wants to take over by 2020 includes India". India Today. 2015.

- ^ "What ISIS and the 'caliphate' mean for Pakistan – DAWN.COM". 3 July 2014.

- ^ Although The Disbelievers Dislike It. Al Furqan Media Foundation. 2014.

- ^ "Although the Disbelievers Dislike It - the Hidden Message". 17 November 2014.

- ^ a b Contextualizing Radicalization Across the World (PDF). The Centre for Security Studies. 2020.

- ^ Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 25.

- ^ Robert Postings (30 April 2019). "Islamic State recognizes new Central Africa Province, deepening ties with DR Congo militants". Defense Post. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ FlorCruz, Michelle (25 September 2014). "Philippine Terror Group Abu Sayyaf May Be Using ISIS Link For Own Agenda". International Business Times. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Mali-Sahel: lutte de positionnement des groupes jihadistes". Radio France Internationale (in French). 6 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b Pellegrino, Chiara (23 December 2015). "A Brief History of ISIS "Provinces"".

- ^ a b McBurney, Niamh (7 April 2017). "'Wilayat Haramayn': Confronting Islamic State in Saudi Arabia". Jamestown.

- ^ Winter, Charlie; al-Tamimi, Aymenn (27 April 2019). "ISIS Relaunches as a Global Platform". The Atlantic.

- ^ "ISIS announces new India and Pakistan provinces, casually breaking up Khorasan". The Defense Post. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "IS Delineates "Khorasan Province" from "Pakistan Province" in Attack Claims, One Involving Targeted Killing in Rawalpindi". Jihadist Threat. SITE Intelligence Group. 24 November 2021. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Fahmy, Omar; Bayoumy, Yara (16 February 2015). "Egypt strikes back at Islamic State militants after beheading video, killing dozens". The Age. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Sinai Province: Egypt's most dangerous group". BBC News. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Anzalone (2018), p. 16.

- ^ Arvisais, Olivier; Guidère, Mathieu (2020). "Education in conflict: how Islamic State established its curriculum". Journal of Curriculum Studies. 52 (4): 498–515. doi:10.1080/00220272.2020.1759694. S2CID 218925756.

- ^ al-Tamimi, Aymenn (2015). "The Evolution in Islamic State Administration: The Documentary Evidence". Perspectives on Terrorism. 9 (4). Terrorism Research Initiative: 117–129. JSTOR 26297420.

- ^ The Structure of the Caliphate. Al-Furqan Media Foundation. 6 July 2016.

- ^ Jefferis, Jennifer. "ISIS Administrative and Territorial Organization". Washington, D.C.: Near East and South Asia Centre for Strategic Studies.

- ^ Education in Mosul under the Islamic State (ISIS): 2015–2016 (PDF). Mosul: Iraqi Institution for Development.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini; Prickett, Ivor (4 April 2018). "The ISIS Files: When Terrorists Run City Hall". The New York Times.

- ^ "Islamic State NHS-style hospital video posted". BBC. 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b Guidère, Mathieu (20 September 2017). Historical Dictionary of Islamic Fundamentalism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538106709.

- ^ Gerges, Fawaz A. (2 November 2021). ISIS: A History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691211923.

- ^ Bunzel, Cole (2019). "Ideological Infighting in the Islamic State" (PDF). Perspectives on Terrorism. ISSN 2334-3745.

- ^ Teiner, David (2021). The Islamic State's Rebel Governance: A Combined Approach of Conceptual Classification and Qualitative Analysis of Administrative Documents (PDF). University of Trier.

- ^ a b "Reduced, but Rebuilding: United Nations Reports on Islamic State and Al-Qaeda".

- ^ a b "The General Directorate of Provinces: Managing the Islamic State's Global Network". 26 July 2023.

- ^ a b "A Globally Integrated Islamic State". 15 July 2024.

- ^ @jseldin (19 July 2022). "The other #ISIS networks" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Chulov, Martin (24 March 2019). "The Rise and Fall of the Isis 'Caliphate'". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Houry, Nadim (5 February 2019). "Bringing ISIS to Justice: Running Out of Time?". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Nebehay, Stephanie (2 October 2014). "Islamic State committing 'staggering' crimes in Iraq: U.N. report". Reuters. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Iraq's Criminal Laws Preclude Justice for Women and Girls". Global Justice Center. 26 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Speckhard, Anne (24 January 2019). "The Punishments of the Islamic State – ICSVE". Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Syria: ISIS Summarily Killed Civilians". Human Rights Watch. 14 June 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Syria conflict: Amnesty says ISIS killed seven children in north". BBC News. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "NGO: ISIS kills 102-year-old man, family in Syria". Al Arabiya English. Agence France-Presse. 1 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Holmes, Oliver (28 December 2014). "Islamic State executed nearly 2,000 people in six months: monitor". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Bacchi, Umberto. "ISIS Medieval School Curriculum: No Music, Art and Literature for Mosul Kids". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (16 September 2014). "Islamic State issues new school curriculum in Iraq". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "ISIS eradicates art, history and music from curriculum in Iraq". CBS News. 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Sabah, Zaid; Al-Ansary, Khalid (17 September 2014). "Mosul Schools Go Back in Time With Islamic State Curriculum". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Philp, Catherine (17 September 2014). "Parents boycott militants' curriculum". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Islamic State says women in Mosul must wear full veil or be punished". The Irish Times. 26 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ McElroy, Damien (23 July 2014). "Islamic State tells Mosul shopkeepers to cover up naked mannequins". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "ISIS Is Actively Recruiting Female Fighters To Brutalize Other Women". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Zelin, Aaron Y. (13 June 2014). "The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria Has a Consumer Protection Office". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (12 June 2014). "The rules in ISIS' new state: Amputations for stealing and women to stay indoors". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 December 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "ISIS bans music, imposes veil in Raqqa". Al-Monitor. 20 January 2014. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Crime and punishment in Saudi Arabia: The other beheaders". The Economist. 20 September 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Isis executes more than 4,000 people in less than two years". Independent. 30 April 2016. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "IS beheads two civilian women in Syria: monitor Archived 4 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine". Yahoo News. 30 June 2015.

- ^ Saul, Heather (22 January 2015). "Isis publishes penal code listing amputation, crucifixion and stoning as punishments – and vows to vigilantly enforce it". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (18 January 2015). "Isis throws 'gay' men off tower, stones woman accused of adultery and crucifies 17 young men in 'retaliatory' wave of executions". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Rush, James (3 February 2015). "Images emerge of 'gay' man 'thrown from building by Isis militants before he is stoned to death after surviving fall'". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Daragahi, Borzou (25 February 2015). "Isis brutality in Iraq reawakens Sunni resistance". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "ISIS Fast Facts". CNN. 6 September 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "FN: IS har begått ohyggliga brott mot mänskligheten". Omni (in Swedish). Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Puppincck, Gregor (October 2017). "ISIS Crimes: Justice Must Be Done!". European Centre for Law & Justice. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Wille, Belkis (3 August 2018). "Four Years on, Evidence of ISIS Crimes Lost to Time". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Labott, Elise; Kopan, Tal (17 March 2016). "John Kerry: ISIS responsible for genocide". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "UN accuses the "Islamic State" in the genocide of the Yazidis" (in Russian). BBC Russian Service/BBC. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "The UN has blamed 'Islamic State' in the genocide of the Yazidis". Радио Свобода. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ Allison, Christine (20 February 2004). "Yazidis i: General". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Cömert, İlhan Yılmaz (12 July 2017). "IŞİD'ın Irak'ta Türkmen Coğrafyasındaki Katliamları" [ISIS Massacres in Turkmen Region in Iraq]. 21yyte.org (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "albarlaman aleiraqiu yuetabar jarayim "daeish" bihaqi alturkuman 'iibadat jamaeiatan" البرلمان العراقي يعتبر جرائم "داعش" بحق التركمان إبادة جماعية [The Iraqi Parliament considers ISIS crimes against the Turkmen to be genocide]. www.aa.com.tr (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Iraqi parliament recognizes ISIS persecution of Turkmen as genocide". Rudaw Media Network. 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ McKay, Hollie (5 March 2021). "The ISIS War Crime Iraqi Turkmen Won't Talk About". New Lines Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Baban, Goran (4 February 2021). "Turkmen women call to uncover fate of 1300 missing Turkmen abducted by ISIS". Kirkuknow. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Rodriguez, Meredith (8 August 2014). "Chicago-area Assyrians march against ISIL, others protest airstrikes". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.