Irving Segal

Irving Segal | |

|---|---|

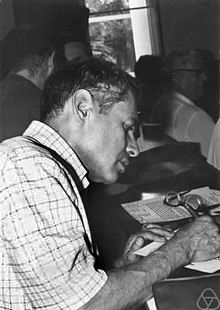

Segal in Nice, 1970 | |

| Born | September 13, 1918 |

| Died | August 30, 1998 (aged 79) Lexington, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Segal–Bargmann space Segal–Shale–Weil representation Gelfand–Naimark–Segal construction Oscillator representation |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Einar Hille |

| Doctoral students | John C. Baez Robert J. Blattner Lester Dubins Henry Dye Abel Klein Bertram Kostant Ray Kunze Ernest Michael Edward Nelson David Shale Isadore Singer W. Forrest Stinespring Walter A. Strauss Robert R. Kallman |

Irving Ezra Segal (1918–1998) was an American mathematician known for work on theoretical quantum mechanics. He shares credit for what is often referred to as the Segal–Shale–Weil representation.[1][2][3] Early in his career Segal became known for his developments in quantum field theory and in functional and harmonic analysis, in particular his innovation of the algebraic axioms known as C*-algebra.

Biography

[edit]Irving Ezra Segal was born in the Bronx on September 13, 1918, to Jewish parents.[4] He attended school in Trenton. In 1934 he was admitted to Princeton University, at the age of 16. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, completed his undergraduate studies in just three years time, graduated with highest honors with a bachelor's degree in 1937, and was awarded the George B. Covington Prize in Mathematics. He was then admitted to Yale, and in another three years time had completed his doctorate, receiving his Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1940. Segal taught at Harvard University, then he joined the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton on a Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, working from 1941 to 1943 with Albert Einstein and John von Neumann. During World War II Segal served in the US Army conducting research in ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. He joined the mathematics department at the University of Chicago in 1948 where he served until 1960. In 1960 he joined the mathematics department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he remained as a professor until his death in 1998. During his career he supervised 40 doctoral students — 15 at the University of Chicago and 25 at M.I.T.[5] He won three Guggenheim Fellowships, in 1947, 1951 and 1967, and received the Humboldt Award in 1981. He was an Invited Speaker of the International Congress of Mathematicians in 1966 in Moscow and in 1970 in Nice. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1973.

In 1983 Victor Guillemin edited a festschrift dedicated to Irving Segal.[6] Physics Today published a review of Introduction to Algebraic and Constructive Quantum Field Theory (1992), which Segal coauthored.[7]

Segal died in Lexington, Massachusetts, on August 30, 1998. Edward Nelson's obituary article about Segal concludes: "... It is rare for a mathematician to produce a life work that at the time can be fully and confidently evaluated by no one, but the full impact of the work of Irving Ezra Segal will become known only to future generations."[8]

Chronometric cosmology

[edit]Segal provided an alternative to the Big Bang theory of expansion of the universe. The cosmological redshift that motivates the expanding universe theory is due to curvature of the cosmos, according to Segal. Spacetime symmetry is expressed by the Lorentz group and its extension the Poincaré group. “The inclusion of the Einstein temporal evolution among the fundamental symmetries gives rise to the conformal group...”[9] But conformal compactification introduces closed timelike curves so Segal portrayed the spatial part of the cosmos as a large 3-sphere with an auxiliary real line for time. Spacetime cannot turn back on itself. At each point in the cosmos there is a convex future direction, meaning, "the future can never merge into the past", no spacetime curvature can close or loop.[10]

Segal reviewed redshift data to verify his cosmology. He claimed confirmation, but generally his chronometric cosmology has not found favor. For instance, Abraham H. Taub reviewed Mathematical Cosmology and Extragalactic Astronomy, saying

The chronometric theory as described in this book is not a theory concerning the nature of the universe nor the behaviour of objects in it. Rather it ignores the effect of gravitational forces on these objects, postulates that astronomical bodies in it are at rest without explaining how this happens and ascribes the redshift to a particular description of methods of measurement which is at variance with that used in theories such as general relativity.[11]

As for the cosmic microwave background, in the chronometric view, "The observed blackbody... is simply the most likely disposition of remnants of light on a purely random basis... and is not at all uniquely indicative of a Big Bang."[12]

In 2005 A. Daigneault spoke on "Irving Segal's Axiomatization of Spacetime and its Cosmological Consequences" in Budapest.[13]

The cosmological consequences of [Segal's] assumptions fly in the face of present day dogmas in cosmology: the universe is eternal; there is no such thing as the expansion of the universe and no such thing as a Big Bang; space is a hypersphere i.e. a three-dimensional sphere of fixed radius; the principle of energy conservation is reestablished; the redshift phenomenon is no Doppler effect but is an effect of the curvature of space ... (page 3)

He concedes at the outset that Segal's cosmology is "generally ignored by astrophysicists", and that the model was first proposed by Einstein in 1917 and is "supposedly discredited".

Selected publications

[edit]For a list of 227 articles and 10 books to which Segal contributed, see the MIT external link below.

- 1951: Segal, Irving Ezra (1951). Decompositions of operator algebras, I and II. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, no. 9. ISBN 9780821812099.

- 1962: Lectures at the Boulder Summer Seminar, American Mathematical Society

- 1963: Mathematical problems of relativistic physics. Lectures in Applied Mathematics, vol. 2. American Mathematical Soc. 1967; with an appendix by George W. Mackey

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1968: (with Ray Kunze) Integrals and operators. McGraw-Hill. 1968. Revised & enlarged 2nd edition. Grundlehren der mathematische Wissenschaften, vol. 228. Springer-Verlag. 2012-12-06. ISBN 9783642666933; pbk reprint of 1978 2nd edition

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1976: Mathematical cosmology and extragalactic astronomy. Pure and Applied Mathematics Series, Vol. 68. Academic Press. 1976-02-19. ISBN 9780080873848.

- 1992: (with John C. Baez and Zhengfang Zhou) Baez, J. C.; Segal, I. E.; Zhou, Z.; Kon, Mark A. (1993). "Introduction to algebraic and constructive quantum field theory". Physics Today. 46 (12). Princeton University Press: 43. Bibcode:1993PhT....46l..43B. doi:10.1063/1.2809125. Baez, John C.; Segal, Irving E.; Zhou, Zhengfang (2014-07-14). 2014 reprint. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400862504.

- 1993: (with Nicoll, J.F., Wu, P., Zhou, Z.) Statistically Efficient Testing of the Hubble and Lundmark Laws on IRAS Galaxy Samples, The Astrophysical Journal 465–484

- 1995: (with Zhou, Z.) Maxwell's Equations in the Einstein Universe and Chronometric Cosmology, ApJS. Ser. 100, 307–324

- 1997: "Cosmic time dilation", The Astrophysical Journal 482:L115–17

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shale, D. (1962). "Linear symmetries of free boson fields". Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 103: 149–167. doi:10.1090/s0002-9947-1962-0137504-6.

- ^ Weil, A. (1964). "Sur certains groupes d'opérateurs unitaires". Acta Math. 111: 143–211. doi:10.1007/BF02391012.

- ^ Kashiwara, M; Vergne, M. (1978). "On the Segal–Shale–Weil representation and harmonic polynomials". Inventiones Mathematicae. 44: 1–47. Bibcode:1978InMat..44....1K. doi:10.1007/BF01389900. S2CID 121545402.

- ^ "Irving Ezra Segal – Biography". Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ "Who's That Mathematician? Paul R. Halmos - Page 48". Mathematical Association of America.

- ^ Victor Guillemin editor (1983) Studies in Applied Mathematics: a Volume Dedicated to Irving Segal, Academic Press ISBN 012305480X

- ^ Kon, Mark A. (1993). "Review of Introduction to Algebraic and Constructive Quantum Field Theory by J. C. Baez, I. E. Segal, and Z. Zhou" (PDF). Physics Today. 46 (12): 43. Bibcode:1993PhT....46l..43B. doi:10.1063/1.2809125.

- ^ Obituary in Americal Mathematical Society Notices

- ^ Segal, I.E, Zhou, Z. (1995) Maxwell's Equations in the Einstein Universe and Chronometric Cosmology", ApJS. Ser. 100, 307–324

- ^ Segal, I.E., 1997, Cosmic time dilation, Ap. J. 482:L115-17

- ^ Taub, A. H. (1977). "Review of Mathematical Cosmology and Extragalactic Astronomy by Irving Ezra Segal". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 83: 705–711. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1977-14356-5.

- ^ Aubert Daigneault (2005) "Standard Cosmology and Other Possible Universes", chapter 13 of Physics Before and After Einstein, M.M. Capria editor, IOS Press ISBN 1-58603-462-6 doi:10.3233/978-1-58603-462-7-285

- ^ A. Daigneault (2005) arXiv preprint, Irving Segal's Axiomatization of Spacetime and its Cosmological Consequences, invited lecture at Budapest. See also Daigneault, Aubert; Sangalli, Arturo (2001). "Einstein's Static Universe: An Idea Whose Time Has Come Back?" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 48: 9–16.

- Habermann, Katharina; Habermann, Lutz (2006), Introduction to Symplectic Dirac Operators, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-33420-0

External links

[edit]- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Irving Segal", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Irving Segal at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- "Publications of Irving Segal" (PDF). math.mit.edu.

- John C. Baez (1999) Memories of Irving Segal

- Leonard Gross and William Segal, "Irving E. Segal", Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (2022)

- 1918 births

- 1998 deaths

- Princeton University alumni

- Yale University alumni

- Harvard University Department of Mathematics faculty

- 20th-century American mathematicians

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Science faculty

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- 20th-century American Jews