Dihydrogen cation

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| H2+ | |

| Molar mass | 2.015 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

The dihydrogen cation or hydrogen molecular ion is a cation (positive ion) with formula . It consists of two hydrogen nuclei (protons), each sharing a single electron. It is the simplest molecular ion.

The ion can be formed from the ionization of a neutral hydrogen molecule () by electron impact. It is commonly formed in molecular clouds in space by the action of cosmic rays.

The dihydrogen cation is of great historical, theoretical, and experimental interest. Historically it is of interest because, having only one electron, the equations of quantum mechanics that describe its structure can be solved approximately in a relatively straightforward way, as long as the motion of the nuclei and relativistic and quantum electrodynamic effects are neglected. The first such solution was derived by Ø. Burrau in 1927,[1] just one year after the wave theory of quantum mechanics was published.

The theoretical interest arises because an accurate mathematical description, taking into account the quantum motion of all constituents and also the interaction of the electron with the radiation field, is feasible. The description's accuracy has steadily improved over more than half a century, eventually resulting in a theoretical framework allowing ultra-high-accuracy predictions for the energies of the rotational and vibrational levels in the electronic ground state, which are mostly metastable.

In parallel, the experimental approach to the study of the cation has undergone a fundamental evolution with respect to earlier experimental techniques used in the 1960s and 1980s. Employing advanced techniques, such as ion trapping and laser cooling, the rotational and vibrational transitions can be investigated in extremely fine detail. The corresponding transition frequencies can be precisely measured and the results can be compared with the precise theoretical predictions. Another approach for precision spectroscopy relies on cooling in a cryogenic magneto-electric trap (Penning trap); here the cations' motion is cooled resistively and the internal vibration and rotation decays by spontaneous emission. Then, electron spin resonance transitions can be precisely studied.

These advances have turned the dihydrogen cations into one more family of bound systems relevant for the determination of fundamental constants of atomic and nuclear physics, after the hydrogen atom family (including hydrogen-like ions) and the helium atom family.[2]

Physical properties

[edit]Bonding in can be described as a covalent one-electron bond, which has a formal bond order of one half.[3]

The ground state energy of the ion is -0.597 Hartree.[4]

The bond length in the ground state is 2.00 Bohr radius.

Isotopologues

[edit]The dihydrogen cation has six isotopologues. Each of the two nuclei can be one of the following: proton (p, the most common one), deuteron (d), or triton (t).[5][6]

- (dihydrogen cation, the common one)[5][6]

- (hydrogen deuterium cation)[5]

- (dideuterium cation)[5][6]

- (hydrogen tritium cation)

- (deuterium tritium cation)

- (ditritium cation)[6]

Quantum mechanical analysis

[edit]Clamped-nuclei approximation

[edit]An approximate description of the dihydrogen cation starts with the neglect of the motion of the nuclei - the so-called clamped-nuclei approximation. This is a good approximation because the nuclei (proton, deuteron or triton) are more than a factor 1000 heavier than the electron. Therefore, the motion of the electron is treated first, for a given (arbitrary) nucleus-nucleus distance R. The electronic energy of the molecule E is computed and the computation is repeated for different values of R. The nucleus-nucleus repulsive energy e2/(4πε0R) has to be added to the electronic energy, resulting in the total molecular energy Etot(R).

The energy E is the eigenvalue of the Schrödinger equation for the single electron. The equation can be solved in a relatively straightforward way due to the lack of electron–electron repulsion (electron correlation). The wave equation (a partial differential equation) separates into two coupled ordinary differential equations when using prolate spheroidal coordinates instead of cartesian coordinates. The analytical solution of the equation, the wave function, is therefore proportional to a product of two infinite power series.[7] The numerical evaluation of the series can be readily performed on a computer. The analytical solutions for the electronic energy eigenvalues are also a generalization of the Lambert W function[8] which can be obtained using a computer algebra system within an experimental mathematics approach.

Quantum chemistry and Physics textbooks usually treat the binding of the molecule in the electronic ground state by the simplest possible ansatz for the wave function: the (normalized) sum of two 1s hydrogen wave functions centered on each nucleus. This ansatz correctly reproduces the binding but is numerically unsatisfactory.

Historical notes

[edit]Early attempts to treat using the old quantum theory were published in 1922 by Karel Niessen[9] and Wolfgang Pauli,[10] and in 1925 by Harold Urey.[11]

The first successful quantum mechanical treatment of was published by the Danish physicist Øyvind Burrau in 1927,[1] just one year after the publication of wave mechanics by Erwin Schrödinger.

In 1928, Linus Pauling published a review putting together the work of Burrau with the work of Walter Heitler and Fritz London on the hydrogen molecule.[12]

The complete mathematical solution of the electronic energy problem for H+

2 in the clamped-nuclei approximation was provided by Wilson (1928) and Jaffé (1934). Johnson (1940) gives a succinct summary of their solution,.[7]

The solutions of the clamped-nuclei Schrödinger equation

[edit]

2 with clamped nuclei A and B, internuclear distance R and plane of symmetry M.

The electronic Schrödinger wave equation for the hydrogen molecular ion H+

2 with two fixed nuclear centers, labeled A and B, and one electron can be written as

where V is the electron-nuclear Coulomb potential energy function:

and E is the (electronic) energy of a given quantum mechanical state (eigenstate), with the electronic state function ψ = ψ(r) depending on the spatial coordinates of the electron. An additive term 1/R, which is constant for fixed internuclear distance R, has been omitted from the potential V, since it merely shifts the eigenvalue. The distances between the electron and the nuclei are denoted ra and rb. In atomic units (ħ = m = e = 4πε0 = 1) the wave equation is

We choose the midpoint between the nuclei as the origin of coordinates. It follows from general symmetry principles that the wave functions can be characterized by their symmetry behavior with respect to the point group inversion operation i (r ↦ −r). There are wave functions ψg(r), which are symmetric with respect to i, and there are wave functions ψu(r), which are antisymmetric under this symmetry operation:

The suffixes g and u are from the German gerade and ungerade) occurring here denote the symmetry behavior under the point group inversion operation i. Their use is standard practice for the designation of electronic states of diatomic molecules, whereas for atomic states the terms even and odd are used. The ground state (the lowest state) of is denoted X2Σ+

g[13] or 1sσg and it is gerade. There is also the first excited state A2Σ+

u (2pσu), which is ungerade.

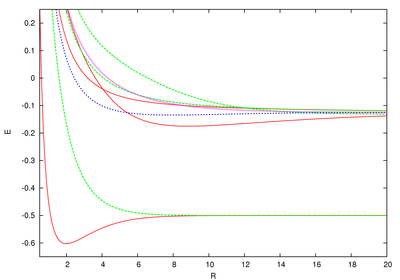

2 as a function of internuclear distance (R, in Bohr radii, the atomic unit of length). See text for details.

Asymptotically, the (total) eigenenergies Eg/u for these two lowest lying states have the same asymptotic expansion in inverse powers of the internuclear distance R:[14][15]

This and the energy curves include the internuclear 1/R term. The actual difference between these two energies is called the exchange energy splitting and is given by:[16]

which exponentially vanishes as the internuclear distance R gets greater. The lead term 4/eRe−R was first obtained by the Holstein–Herring method. Similarly, asymptotic expansions in powers of 1/R have been obtained to high order by Cizek et al. for the lowest ten discrete states of the hydrogen molecular ion (clamped nuclei case). For general diatomic and polyatomic molecular systems, the exchange energy is thus very elusive to calculate at large internuclear distances but is nonetheless needed for long-range interactions including studies related to magnetism and charge exchange effects. These are of particular importance in stellar and atmospheric physics.

The energies for the lowest discrete states are shown in the graph above. These can be obtained to within arbitrary accuracy using computer algebra from the generalized Lambert W function (see eq. (3) in that site and reference[8]). They were obtained initially by numerical means to within double precision by the most precise program available, namely ODKIL.[17] The red solid lines are 2Σ+

g states. The green dashed lines are 2Σ+

u states. The blue dashed line is a 2Πu state and the pink dotted line is a 2Πg state. Note that although the generalized Lambert W function eigenvalue solutions supersede these asymptotic expansions, in practice, they are most useful near the bond length.

The complete Hamiltonian of H+

2 (as for all centrosymmetric molecules) does not commute with the point group inversion operation i because of the effect of the nuclear hyperfine Hamiltonian. The nuclear hyperfine Hamiltonian can mix the rotational levels of g and u electronic states (called ortho-para mixing) and give rise to ortho-para transitions.[18][19]

Born-Oppenheimer approximation

[edit]Once the energy function Etot(R) has been obtained, one can compute the quantum states of rotational and vibrational motion of the nuclei, and thus of the molecule as a whole. The corresponding `'nuclear'´ Schrödinger equation is a one-dimensional ordinary differential equation, where the nucleus-nucleus distance R is the independent coordinate. The equation describes the motion of a fictitious particle of mass equal to the reduced mass of the two nuclei, in the potential Etot(R)+VL(R), where the second term is the centrifugal potential due to rotation with angular momentum described by the quantum number L. The eigenenergies of this Schrödinger equation are the total energies of the whole molecule, electronic plus nuclear.

High-accuracy ab initio theory

[edit]The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is unsuited for describing the dihydrogen cation accurately enough to explain the results of precision spectroscopy.

The full Schrödinger equation for this cation, without the approximation of clamped nuclei, is much more complex, but nevertheless can be solved numerically essentially exactly using a variational approach.[20] Thereby, the simultaneous motion of the electron and of the nuclei is treated exactly. When the solutions are restricted to the lowest-energy orbital, one obtains the rotational and ro-vibrational states' energies and wavefunctions. The numerical uncertainty of the energies and the wave functions found in this way is negligible compared to the systematic error stemming from using the Schrödinger equation, rather than fundamentally more accurate equations. Indeed, the Schrödinger equation does not incorporate all relevant physics, as is known from the hydrogen atom problem. More accurate treatments need to consider the physics that is described by the Dirac equation or, even more accurately, by quantum electrodynamics. The most accurate solutions of the ro-vibrational states are found by applying non-relativistic quantum electrodynamics (NRQED) theory.[21]

For comparison with experiment, one requires differences of state energies, i.e. transition frequencies. For transitions between ro-vibrational levels having small rotational and moderate vibrational quantum numbers the frequencies have been calculated with theoretical fractional uncertainty of approximately 8×10−12.[21] Additional contributions to the uncertainty of the predicted frequencies arise from the uncertainties of fundamental constants, which are input to the theoretical calculation, especially from the ratio of the proton mass and the electron mass.

Using a sophisticated ab initio formalism, also the hyperfine energies can be computed accurately, see below.

Experimental studies

[edit]Precision spectroscopy

[edit]Because of its relative simplicity, the dihydrogen cation is the molecule that is most precisely understood, in the sense that theoretical calculations of its energy levels match the experimental results with the highest level of agreement.

Specifically, spectroscopically determined pure rotational and ro-vibrational transition frequencies of the particular isotopologue agree with theoretically computed transition frequencies. Four high-precision experiments yielded comparisons with total uncertainties between 2×10−11 and 5×10−11, fractionally.[22] The level of agreement is actually limited neither by theory not by experiment but rather by the uncertainty of the current values of the masses of the particles, that are used as input parameters to the calculation.

In order to measure the transition frequencies with high accuracy, the spectroscopy of the dihydrogen cation had to be performed under special conditions. Therefore, ensembles of ions were trapped in a quadrupole ion trap under ultra-high vacuum, sympathetically cooled by laser-cooled beryllium ions, and interrogated using particular spectroscopic techniques.

The hyperfine structure of the homonuclear isotopologue has been measured extensively and precisely by Jefferts in 1969. Finally, in 2021, ab initio theory computations were able to provide the quantitative details of the structure with uncertainty smaller than that of the experimental data, 1 kHz. Some contributions to the measured hyperfine structure have been theoretically confirmed at the level of approximately 50 Hz.[23]

The implication of these agreements is that one can deduce a spectroscopic value of the ratio of electron mass to reduced proton-deuteron mass, me/mp+me/md, that is an input to the ab initio theory. The ratio is fitted such that theoretical prediction and experimental results agree. The uncertainty of the obtained ratio is comparable to the one obtained from direct mass measurements of proton, deuteron, electron, and HD+ via cyclotron resonance in Penning traps.

Occurrence in space

[edit]Formation

[edit]The dihydrogen ion is formed in nature by the interaction of cosmic rays and the hydrogen molecule. An electron is knocked off leaving the cation behind.[24]

Cosmic ray particles have enough energy to ionize many molecules before coming to a stop.

The ionization energy of the hydrogen molecule is 15.603 eV. High speed electrons also cause ionization of hydrogen molecules with a peak cross section around 50 eV. The peak cross section for ionization for high speed protons is 70000 eV with a cross section of 2.5×10−16 cm2. A cosmic ray proton at lower energy can also strip an electron off a neutral hydrogen molecule to form a neutral hydrogen atom and the dihydrogen cation, () with a peak cross section at around 8000 eV of 8×10−16 cm2.[25]

Destruction

[edit]In nature the ion is destroyed by reacting with other hydrogen molecules:

Production in the laboratory

[edit]In the laboratory, the ion is easily produced by electron bombardment from an electron gun.

An artificial plasma discharge cell can also produce the ion.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Symmetry of diatomic molecules

- Dirac Delta function model (one-dimensional version of H+

2) - Di-positronium

- Euler's three-body problem (classical counterpart)

- Few-body systems

- Helium atom

- Helium hydride ion

- Trihydrogen cation

- Triatomic hydrogen

- Lambert W function

- Molecular astrophysics

- Holstein–Herring method

- Three-body problem

- List of quantum-mechanical systems with analytical solutions

References

[edit]- ^ a b Burrau, Ø. (1927). "Berechnung des Energiewertes des Wasserstoffmolekel-Ions (H+

2) im Normalzustand" (PDF). Danske Vidensk. Selskab. Math.-fys. Meddel. (in German). M 7:14: 1–18.

Burrau, Ø. (1927). "The calculation of the Energy value of Hydrogen molecule ions (H+

2) in their normal position". Naturwissenschaften (in German). 15 (1): 16–7. Bibcode:1927NW.....15...16B. doi:10.1007/BF01504875. S2CID 19368939.[permanent dead link] - ^ Schiller, S. (2022). "Precision spectroscopy of the molecular hydrogen ions: an introduction". Contemporary Physics. 63 (4): 247–279. Bibcode:2022ConPh..63..247S. doi:10.1080/00107514.2023.2180180.

- ^ Clark R. Landis; Frank Weinhold (2005). Valency and bonding: a natural bond orbital donor-acceptor perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-521-83128-4.

- ^ Bressanini, Dario; Mella, Massimo; Morosi, Gabriele (1997). "Nonadiabatic wavefunctions as linear expansions of correlated exponentials. A quantum Monte Carlo application to H2+ and Ps2". Chemical Physics Letters. 272 (5–6): 370–375. Bibcode:1997CPL...272..370B. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00571-X.

- ^ a b c d Fábri, Csaba; Czakó, Gábor; Tasi, Gyula; Császár, Attila G. (2009). "Adiabatic Jacobi corrections on the vibrational energy levels of H2(+) isotopologues". Journal of Chemical Physics. 130 (13): 134314. Bibcode:2009JChPh.130m4314F. doi:10.1063/1.3097327. PMID 19355739.

- ^ a b c d Scarlett, Liam H.; Zammit, Mark C.; Fursa, Dmitry V.; Bray, Igor (2017). "Kinetic-energy release of fragments from electron-impact dissociation of the molecular hydrogen ion and its isotopologues". Physical Review A. 96 (2): 022706. Bibcode:2017PhRvA..96b2706S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.96.022706. OSTI 1514929.

- ^ a b Johnson, V.A. (1941). "Correction for nuclear motion in H2+". Phys. Rev. 60 (5): 373–77. Bibcode:1941PhRv...60..373J. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.60.373.

- ^ a b Scott, T. C.; Aubert-Frécon, M.; Grotendorst, J. (2006). "New Approach for the Electronic Energies of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion". Chem. Phys. 324 (2–3): 323–338. arXiv:physics/0607081. Bibcode:2006CP....324..323S. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2005.10.031. S2CID 623114.

- ^ Karel F. Niessen Zur Quantentheorie des Wasserstoffmolekülions, doctoral dissertation, University of Utrecht, Utrecht: I. Van Druten (1922) as cited in Mehra, Volume 5, Part 2, 2001, p. 932.

- ^ Pauli W (1922). "Über das Modell des Wasserstoffmolekülions". Annalen der Physik. 373 (11): 177–240. doi:10.1002/andp.19223731101. Extended doctoral dissertation; received 4 March 1922, published in issue No. 11 of 3 August 1922.

- ^ Urey HC (October 1925). "The Structure of the Hydrogen Molecule Ion". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 11 (10): 618–21. Bibcode:1925PNAS...11..618U. doi:10.1073/pnas.11.10.618. PMC 1086173. PMID 16587051.

- ^ Pauling, L. (1928). "The Application of the Quantum Mechanics to the Structure of the Hydrogen Molecule and Hydrogen Molecule-Ion and to Related Problems". Chemical Reviews. 5 (2): 173–213. doi:10.1021/cr60018a003.

- ^ Huber, K.-P.; Herzberg, G. (1979). Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure IV. Constants of Diatomic Molecules. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- ^ Čížek, J.; Damburg, R. J.; Graffi, S.; Grecchi, V.; Harrel II, E. M.; Harris, J. G.; Nakai, S.; Paldus, J.; Propin, R. Kh.; Silverstone, H. J. (1986). "1/R expansion for H+

2: Calculation of exponentially small terms and asymptotics". Phys. Rev. A. 33 (1): 12–54. Bibcode:1986PhRvA..33...12C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.33.12. PMID 9896581. - ^ Morgan III, John D.; Simon, Barry (1980). "Behavior of molecular potential energy curves for large nuclear separations". Int. J. Quantum Chem. 17 (6): 1143–1166. doi:10.1002/qua.560170609.

- ^ Scott, T. C.; Dalgarno, A.; Morgan, J. D. III (1991). "Exchange Energy of H+

2 Calculated from Polarization Perturbation Theory and the Holstein-Herring Method". Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 (11): 1419–1422. Bibcode:1991PhRvL..67.1419S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.1419. PMID 10044142. - ^ Hadinger, G.; Aubert-Frécon, M.; Hadinger, G. (1989). "The Killingbeck method for the one-electron two-centre problem". J. Phys. B. 22 (5): 697–712. Bibcode:1989JPhB...22..697H. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/22/5/003. S2CID 250741775.

- ^ Pique, J. P.; et al. (1984). "Hyperfine-Induced Ungerade-Gerade Symmetry Breaking in a Homonuclear Diatomic Molecule near a Dissociation Limit: 127I2 at the 2P3/2 − 2P1/2 Limit". Phys. Rev. Lett. 52 (4): 267–269. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..52..267P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.267.

- ^ Critchley, A. D. J.; et al. (2001). "Direct Measurement of a Pure Rotation Transition in H+

2". Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (9): 1725–1728. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.1725C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1725. PMID 11290233. - ^ Korobov, V.I. (2022). "Variational Methods in the Quantum Mechanical Three-Body Problem with a Coulomb Interaction". Physics of Particles and Nuclei. 53 (1): 1–20. Bibcode:2022PPN....53....1K. doi:10.1134/S1063779622010038. S2CID 258696598.

- ^ a b Korobov, Vladimir I.; Karr, Jean-Philippe (2021). "Rovibrational spin-averaged transitions in the hydrogen molecular ions". Physical Review A. 104 (3): 032806. arXiv:2107.14497. Bibcode:2021PhRvA.104c2806K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.104.032806. S2CID 236635049.

- ^ Alighanbari, S.; Kortunov, I.V.; Giri, G.G.; Schiller, S. (2023). "Test of charged baryon interaction with high-resolution vibrational spectroscopy of molecular hydrogen ions". Nature Physics. 19 (9): 1263–1269. Bibcode:2023NatPh..19.1263A. doi:10.1038/s41567-023-02088-2. S2CID 259567529.

- ^ Haidar, M.; Korobov, V.I.; Hilico, L.; Karr, J.Ph. (2022). "Higher-order corrections to spin–orbit and spin–spin tensor interactions in hydrogen molecular ions: theory and application to H2+". Physical Review A. 106 (2): 022816. arXiv:2207.01535. Bibcode:2022PhRvA.106b2816H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.106.022816. S2CID 251946960.

- ^ Herbst, E. (2000). "The Astrochemistry of H+

3". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 358 (1774): 2523–2534. Bibcode:2000RSPTA.358.2523H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2000.0665. S2CID 97131120. - ^ Padovani, Marco; Galli, Daniele; Glassgold, Alfred E. (2009). "Cosmic-ray ionization of molecular clouds". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 501 (2): 619–631. arXiv:0904.4149. Bibcode:2009A&A...501..619P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911794. S2CID 7897739.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {[HD]^+=[^1H^2H]^+}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2f97eb6837a7f92e5e1feb36eee2f0decebbe58)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {[HT]^+=[^1H^3H]^+}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5e6153ed34ec9d3924b8a01a538d89c2b716ccc6)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {[DT]^+=[^2H^3H]^+}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/386d3b1f697655123cf9df3e09f6ddca0c726478)

![{\displaystyle \Delta E=E_{u}-E_{g}={\frac {4}{e}}\,R\,e^{-R}\left[\,1+{\frac {1}{2R}}+O\left(R^{-2}\right)\,\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9abc25405617f09082349bc59b37b3afde137f84)