Herstmonceux Castle

| Herstmonceux Castle | |

|---|---|

Herstmonceux Castle, seen from the south-east | |

| Type | Medieval fortified house |

| Location | Herstmonceux |

| Coordinates | 50°52′10″N 0°20′19″E / 50.8695°N 0.3387°E |

| OS grid reference | TQ64511046 |

| Area | East Sussex |

| Built | 1441 |

| Owner | Queen's University at Kingston |

| Official name | Herstmonceux Castle |

| Reference no. | 1002298 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Herstmonceux Castle with attached bridges to north and south and causeway with moat retaining walls to west |

| Designated | 24 July 1989 |

| Reference no. | 1272785 |

| Official name | Herstmonceux Castle and Place |

| Designated | 25 March 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1000231 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Herstmonceux Science Centre |

| Designated | 26 March 2003 |

| Reference no. | 1391813 |

Herstmonceux Castle is a brick-built castle, dating from the 15th century, near Herstmonceux, East Sussex, England. It is one of the oldest significant brick buildings still standing in England.[1] The castle was renowned for being one of the first buildings to use that material in England, and was built using bricks taken from the local clay, by builders from Flanders.[2] It dates from 1441.[3] Construction began under the then-owner, Sir Roger Fiennes, and was continued after his death in 1449 by his son, Lord Dacre.[3] The castle has been owned by Queen's University at Kingston, a Canadian university, since 1993.[4]

The parks and gardens of Herstmonceux Castle and Place are Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[3] Other listed structures on the Herstmonceux estate include the Grade II listed walled garden to the north of the castle,[5] and the Grade II* listed telescopes and workshops of the Herstmonceux Science Centre.[6]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The first written evidence of the existence of the Herst settlement appears in William the Conqueror's Domesday Book of 1086, which reports that one of William's closest supporters granted tenancy of the manor at Herst to a man named 'Wilbert'.[1] By the end of the twelfth century, the family at the manor house at Herst had considerable status. Written accounts mention a lady called Idonea de Herst, who married a Norman nobleman named Ingelram de Monceux. Around this time, the manor began to be called the "Herst of the Monceux", a name that eventually became Herstmonceux.[1]

A descendant of the Monceux family, Roger Fiennes, was ultimately responsible for the construction of Herstmonceux Castle in the County of Sussex. Sir Roger was appointed Treasurer of the Household of Henry VI of England and needed a house fitting a man of his position, so construction of the castle on the site of the old manor house began in 1441. It was this position as treasurer which enabled him to afford the £3,800 construction of the original castle.[7]

In 1541, Sir Thomas Fiennes, Lord Dacre, was tried for murder and robbery of the King's deer after his poaching exploits on a neighboring estate resulted in the death of a gamekeeper. He was convicted and hanged as a commoner, and the Herstmonceux estate was temporarily confiscated by Henry VIII of England, but was restored to the Fiennes family during the reign of one of Henry's children.[8]

The profligacy of the 15th Baron Dacre, heir to the Fiennes family, forced him to sell in 1708 to George Naylor, a lawyer of Lincoln's Inn in London. Bethaia Naylor, who became the heiress of Herstmonceux on the death of her brother's only daughter, married Francis Hare and produced a son, Francis, who inherited in turn, his mother's property. The castle eventually came into the possession of Robert Hare-Naylor, who, upon the insistence of his second wife, Henrietta Henckell, followed the architect Samuel Wyatt's advice to reduce the Castle to a picturesque ruin by demolishing the interior.[9] Thomas Lennard, 17th Baron Dacre, was sufficiently exercised as to commission James Lambert of Lewes to record the building in 1776.[10][11] The castle was dismantled in 1777 leaving the exterior walls standing and remained a ruin until the early 20th century.[12]

20th-century restoration

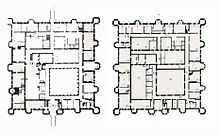

[edit]Radical restoration work was undertaken by Colonel Claude Lowther in 1913 to transform the ruined building into a residence and, based on a design by the architect, Walter Godfrey, this work was completed by Sir Paul Latham in 1933. The existing interiors largely date from that period, incorporating architectural antiques from England and France. The one major change in planning was the combination of the four internal courtyards into one large one. The restoration work, regarded as the apex of Godfrey's architectural achievement, was described by the critic Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as executed 'exemplarily'.[13]

Royal Greenwich Observatory

[edit]

The Royal Observatory was founded by King Charles II at Greenwich in 1675.[14] Observing conditions at Greenwich deteriorated following the urban growth of London, and plans were made in the early 20th century to relocate the observatory to a rural location with clearer, darker skies. Herstmonceux Castle and estate were put up for sale by their private owners and were sold in 1946 to the Admiralty, which then operated the Royal Observatory on behalf of the British government. The relocation of the observatory took place over a decade, and was complete by 1957. A number of new buildings were erected in the castle grounds. The institution at Herstmonceux Castle was known as the Royal Greenwich Observatory, where it remained until 1988, when the observatory relocated to Cambridge.[15]

Several of the telescopes remain but the largest telescope, the 100 inch (254 cm) aperture Isaac Newton Telescope was moved to La Palma, in the Canary Islands, in the 1970s. The estate houses the Equatorial Telescope Group, which is used as the Observatory Science Centre; a publicly accessible science museum, observatory and planetarium. The Observatory Science Centre has taken on the maintenance and upkeep of the grade II* listed observatory, which had fallen into disrepair before their tenancy. The empty dome for the Newton Telescope remains on this site and is a landmark, visible from afar.[16]

University Study Centre

[edit]

In 1992 Alfred Bader, an alumnus of Queen's University at Kingston, learned of the castle's vacancy and offered to purchase the castle for his wife; she declined, joking that there would be "too many rooms to clean".[17] But in 1994, after intensive renovations, the Queen's International Study Centre was opened. It hosts primarily undergraduate students studying arts, science, or commerce through the Canadian University Study Abroad Program (CUSAP), as well as graduate students studying Public International Law or International Business Law. Specialty summer programmes (May–June) including engineering (Global Project Management), archaeology, international health sciences, and law have become popular in recent years with students from both Queen's and other universities.[18] In late January 2009, the ISC was renamed the Bader International Study Centre.[19] As part of the 25th anniversary celebrations, new science and innovation labs were opened on the campus to increase the ability for first year science-tracked students to attend.[20] In 2022, the Bader International Study Centre was renamed Bader College.[21] On 13 November 2023, in response to engineering investigations, the university suspended operations at Bader College and future admissions to Bader College programs until structural remediation activities can be completed. It is expected that these activities will take at least 18 months, with the scope of works required still under investigation.[22]

Historical retinue and events

[edit]Herstmonceux Castle is associated with a retinue of historical re-enactment troops including archers, knights, and falconers, who fly their birds over the grounds.[20] The castle is host to a large medieval weekend in August of each year,[23] and is also hired out for weddings and weekend events.[24]

In popular culture

[edit]The castle was used for filming part of The Silver Chair, a 1990 BBC adaptation of the book (one of The Chronicles of Narnia) by C. S. Lewis. The castle and gardens were used by comedians Reeves and Mortimer for one of their Mulligan and O'Hare sketches. In August 2002, The Coca-Cola Company rented the castle for use as part of a prize in a Harry Potter-themed sweepstakes—the castle served as "Hogwarts" in a day of Harry Potter-related activities for the sweepstakes winners. A "painting" of the castle was used as a magical cursed object in the U.S. television show Charmed – episode 2.3 "The Painted World".[25] Due to its suitable appearance, Herstmonceux Castle was a filming location for the series My Lady Jane.[26]

Owners of Herstmonceux Manor/Castle

[edit]

Owners have been as follows:[27]

- 1066 – Edmer, a priest

- 1086 – Wilbert, tenant-in-chief

- c.1200 – Idonea de Herst (married Ingelram de Monceux)

- 1211 – Her son Waleran de Monceux

- 1216 – His son William de Monceux

- ? – His son Waleran de Monceux

- 1279 – His son John de Monceux

- 1302 – His son John de Monceux

- 1316 – His son John de Monceux

- 1330 – His sister Maud de Monceux (married Sir John Fiennes)

- 1351 – Her eldest son William Fiennes

- 1359 – His son Sir William Fiennes

- 1402 – His son Sir Roger Fiennes (built Herstmonceux Castle)

- 1449 – His son Sir Richard Fiennes (married Joan Dacre, 7th Baroness Dacre)

- 1483 – His grandson Sir Thomas Fiennes

- 1533 – Sir Thomas Fiennes

- 1541 – His eldest son Thomas Fiennes

- 1553 – His brother Gregory Fiennes

- 1594 – His sister Margaret Fiennes (married Sampson Lennard).

- 1612 – Her son Henry Lennard, 12th Baron Dacre

- 1616 – His son Richard Leonard

- 1630 – His son Francis Leonard

- 1662 – His son Thomas Leonard

- 1708 – Estate purchased by George Naylor for £38,215

- 1730 – His nephew Francis Naylor

- 1775 – His half-brother Robert Hare who demolished the castle in 1776

- ? – His son Francis Hare Naylor

- 1807 – Purchased by Thomas Read Kemp

- 1819 – Purchased for John Gillon MP

- 1846 – Purchased by Herbet Barrett Curteis MP

- ? – His son Herbert Mascall Curteis

- ? – His son Herbert Curteis

- 1911 – Purchased by Lieutenant-Colonel Claude Lowther (restoration began)

- 1929 – Purchased by Reginald Lawson

- 1932 – Purchased by Sir Paul Latham (completed restoration under Walter Godfrey)

- 1946 – Purchased by H.M. Admiralty for The Royal Observatory

- 1965 – Transferred to the Science Research Council

- 1989 – Purchased by James Developments, transfers to a receiver, the Guinness Mahon Bank

- 1993 – Purchased for Queen's University, Ontario (Canada) as a gift from Drs. Alfred and Isabel Bader

See also

[edit]- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

- List of sites on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens

- Herstmonceux Place

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b c Venables, Edmund (1851). The Castle of Herstmonceux and its Lords. London: John Russell Smith. p. 169.

- ^ Calvert, David; Martin, Roger (1994). A History of Herstmonceux Castle. Canada: International Study Centre. pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Historic England, "Herstmonceux Castle and Place (1000231)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 September 2016

- ^ "Our History". Bader College, UK. Queen's University at Kingston. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Historic England, "Walled Garden to North of Herstmonceux Castle (1243641)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 September 2016

- ^ Historic England, "Herstmonceux Science Centre (1391813)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 26 September 2016

- ^ Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0521581325.

- ^ Fiennes, Ranulph (2009). Mad Dogs and Englishmen: An Expedition Round My Family.

- ^ Hare, Augustus. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 24. pp. 374–375.

- ^ Farrant, John H. (2010). "The drawings of Herstmonceux Castle by James Lambert, senior and junior, 1776–7" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 148: 177–181. doi:10.5284/1086517.

- ^ artfund.org: "Leather bound folio of 77 watercolours and drawings of Sussex by James Lambert Senior"

- ^ "Herstmonceux Castle c.1806–10". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0140710281.

- ^ "History of The Royal Observatory". The Observatory Science Centre.

- ^ "Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives". Cambridge University Library. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "A dome, with vision". The Telegraph. 31 July 2001. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Royal Institute of Chemistry 1993, p. 922

- ^ "Bader International Study Centre Upper-Year Programmes". Queen's University. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Bader International Study Centre". Queen's University. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Silver celebration at The Castle". Queen's University. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Bader International Study Centre renamed to Bader College". The Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Update on operations at Bader College | Bader College". www.queensu.ca. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Medieval Festival Information". Malcolm Group Events Ltd. 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Home – Herstmonceux Castle – Gardens & Grounds, Sussex". herstmonceux-castle.com. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Avery, Martin. Love And Happiness In The Empires Of The Past, The Present, And The Future. ISBN 978-1312734456.

- ^ Shah, Furvah (12 July 2024). "Where was My Lady Jane filmed?". Cosmpolitan. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Venables, The Rev. Edmund (1851). "The Castle of Herstmonceux and its Lords". Sussex Archaeological Society. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Bibliography

- Royal Institute of Chemistry (1993), Chemistry in Britain, vol. 29, Chemical Education Trust Fund for the Chemical Society and the Royal Institute of Chemistry

- Farrant, John H. (2010). "The drawings of Herstmonceux Castle by James Lambert, senior and junior, 1776–7" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 148: 177–181. doi:10.5284/1086517.

- John Goodall in Burlington Magazine (August 2004).

- Nairn, Ian; Nikolaus Pevsner (1965). Sussex (Buildings of England series). London: Penguin Books.

External links

[edit]- Official website of Herstmonceux Castle

- Queen's University (Canada)'s Bader International Study Centre at Herstmonceux Castle

- The Observatory Science Centre, Herstmonceux

- Map of the Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux

- A Personal History of the Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux Castle, 1948–1990 by George Wilkins, a former member of staff