Human reproductive system

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

| Human reproductive system | |

|---|---|

Internal genitalia of a human female (left) and male (right). | |

External genitalia of an adult female (left) and male (right). | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | systemata genitalia |

| TA98 | A09.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 3467 |

| FMA | 7160 75572, 7160 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human reproductive system includes the male reproductive system, which functions to produce and deposit sperm, and the female reproductive system, which functions to produce egg cells and to protect and nourish the fetus until birth. Humans have a high level of sexual differentiation. In addition to differences in nearly every reproductive organ, there are numerous differences in typical secondary sex characteristics.

Human reproduction usually involves internal fertilization by sexual intercourse. In this process, the male inserts his penis into the female's vagina and ejaculates semen, which contains sperm. A small proportion of the sperm pass through the cervix into the uterus and then into the fallopian tubes for fertilization of the ovum. Only one sperm is required to fertilize the ovum. Upon successful fertilization, the fertilized ovum, or zygote, travels out of the fallopian tube and into the uterus, where it implants in the uterine wall. This marks the beginning of gestation, better known as pregnancy, which continues for around nine months as the fetus develops. When the fetus has developed to a certain point, pregnancy is concluded with childbirth, involving labor. During labor, the uterine muscles contract, and the cervix dilates typically over a period of hours, allowing the infant to pass from the uterus through the vagina.[1] Human infants are entirely dependent on their caregivers and require parental care. Infants rely on their caregivers for comfort, cleanliness, and food. Food may be provided by breastfeeding or formula feeding.[2]

Structure

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Female

[edit]

The human female reproductive system is a series of organs primarily located inside the body and around the pelvic region of a female that contribute towards the reproductive process. The human female reproductive system contains three main parts: the vagina, which leads from the vulva, the vaginal opening, to the uterus; the uterus, which holds the developing fetus; and the ovaries, which produce the female's ova. The breasts are involved during the parenting stage of reproduction, but in most classifications they are not considered to be part of the female reproductive system.[3]

The vagina meets the outside at the vulva, which is made up of the labia, clitoris and vestibule;[4] during intercourse this area is lubricated by mucus secreted by the Bartholin's glands. The vagina is attached to the uterus through the cervix, while the uterus is attached to the ovaries via the fallopian tubes. Each ovary contains hundreds of egg cells or ova (singular ovum).

Approximately every 28 days, the pituitary gland releases a hormone that stimulates some of the ova to develop and grow. One ovum is released and it passes through the fallopian tube into the uterus. Hormones produced by the ovaries prepare the uterus to receive the ovum. The lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, and unfertilized ova are shed each cycle through the process of menstruation. If the ova is fertilized by sperm, it attaches to the endometrium and the fetus develops.[3]

Male

[edit]

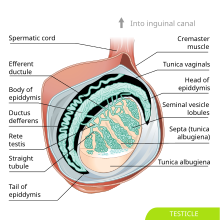

The male reproductive system is a series of organs located outside the body and around the pelvis region of a male that contribute towards the reproduction process. The primary direct function of the male reproductive system is to provide the male sperm for fertilization of the ovum.[3]

The major reproductive organs of the male can be grouped into three categories. The first category produces and stores sperm (spermatozoa). These are produced in the testicles, which are housed in the temperature-regulating scrotum; immature sperm then travel to the epididymides for development and storage. The second category are the ejaculatory fluid producing glands which include the Cowper's gland (also called bulbourethral gland), seminal vesicles, prostate, and vas deferens. The final category are those used for copulation and deposition of the sperm within the female; these include the penis, urethra, and vas deferens.[3]

Major secondary sexual characteristics include a larger, more muscular stature, deepened voice, facial and body hair, broad shoulders, and the development of an Adam's apple.[5] An important sexual hormone of males is androgen, particularly testosterone.[6]

The testes release a hormone that controls the development of sperm. This hormone is also responsible for the development of physical characteristics in men, such as facial hair and a deep voice.

Development

[edit]The development of the reproductive system and the development of the urinary system are closely tied to the development of the human fetus. Despite the differences between them, the adult male and female are determined in early development in the 6th week. The gonads and external genitals are derived from the intermediate mesoderm.[7] The three main fetal precursors of the reproductive organs are the Wolffian duct, the Müllerian ducts, and the gonads. Endocrine hormones are a well-known and critical controlling factor in the normal differentiation of the reproductive system.[8]

The Wolffian duct forms the epididymis, vas deferens, ejaculatory duct, and seminal vesicle in the male reproductive system, but essentially disappears in the female reproductive system.[9] The reverse is true for the Müllerian duct, as it essentially disappears in the male reproductive system and forms the fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina in the female system. In both sexes, the gonads go on to form the testes and ovaries; because they are derived from the same undeveloped structure, they are considered homologous organs. There are a number of other homologous structures shared between male and female reproductive systems. However, despite the similarity in function of the female fallopian tubes and the male epididymis and vas deferens, they are not homologous but rather analogous structures as they arise from different fetal structures.

Reproduction

[edit]Production of gametes

[edit]Gametes are produced within the gonads through a process known as gametogenesis. This occurs when certain types of germ cells undergo meiosis to split the normal diploid number of chromosomes (n=46) into haploid cells containing only 23 chromosomes.[10]

In males, this process is known as spermatogenesis and occurs only after puberty in the seminiferous tubules of the testes. The immature spermatozoa or sperm are then sent to the epididymis, where they gain a tail, enabling motility. Each of the original diploid germ cells or primary spermatocytes forms four functional gametes, each forever young.[clarification needed] The production and survival of sperms require a temperature below the normal core body temperature. Since the scrotum, where the testes is present, is situated outside the body cavity, it provides a temperature about 3 °C below normal body temperature.

In females, gametogenesis is known as oogenesis; this occurs in the ovarian follicles of the ovaries. This process does not produce mature ovum until puberty. In contrast with males, each of the original diploid germ cells or primary oocytes will form only one mature ovum, and three polar bodies which are not capable of fertilization. It has long been understood that in females, unlike males, all the primary oocytes ever found in a female will be created prior to birth, and that the final stages of ova production will then not resume until puberty.[10] However, recent scientific research has challenged that hypothesis.[11] This new research indicates that in at least some species of mammal, oocytes continue to be replenished in females well after birth.[12]

In male germ cells and spermatozoa, and also in female oocytes, special DNA repair mechanism are present that function to maintain the integrity of the genomes that are to be passed on to progeny.[13] These DNA repair pathways include homologous recombinational repair, non-homologous end joining, base excision repair and DNA mismatch repair.[13]

Disease

[edit]Like all complex organ systems, the human reproductive system is affected by many diseases. There are four main categories of reproductive diseases in humans. They are:

- Genetic or congenital abnormalities.

- Cancers.

- Infections, which are often sexually transmitted infections.

- Varicocele [14]

- Functional problems caused by environmental factors, physical damage, psychological issues, autoimmune disorders, or other causes. The best-known functional problems include sexual dysfunction and infertility, which are both broad terms relating to many disorders with many causes.

Specific reproductive diseases are often symptoms of other diseases and disorders, or have multiple, or unknown causes making them difficult to classify. Examples of unclassifiable disorders are Peyronie's disease in males and endometriosis in females. Many congenital conditions cause reproductive abnormalities, but are better known for their other symptoms. These include: Turner syndrome, Klinefelter's syndrome, cystic fibrosis, and Bloom syndrome.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ Hanley, Gillian E.; Munro, Sarah; Greyson, Devon; Gross, Mechthild M.; Hundley, Vanora; Spiby, Helen; Janssen, Patricia A. (2016). "Diagnosing onset of labor: a systematic review of definitions in the research literature". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 16 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0857-4. PMC 4818892. PMID 27039302.

- ^ Sexual Reproduction in Humans. Archived 2018-02-17 at the Wayback Machine 2006. John W. Kimball. Kimball's Biology Pages, and online textbook.

- ^ a b c d "BIO304-14.1-Brief overview of Male and Female Reproductive System" (PDF). Saylor.org. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Nguyen, John D.; Duong, Hieu (2024), "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Female External Genitalia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31613483, retrieved 2024-06-21

- ^ "Puberty guide: Signs and stages for boys and girls". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2020-10-07. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ "Testosterone — What It Does And Doesn't Do". Harvard Health. 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Rey, Rodolfo; Josso, Nathalie; Racine, Chrystèle (2000), Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Blackman, Marc R.; Boyce, Alison (eds.), "Sexual Differentiation", Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc., PMID 25905232, retrieved 2023-12-19

- ^ EDRI Federal Project Inventory: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Abnormal Reproductive Development Archived 2008-12-06 at the Wayback Machine US EPA. Dr. William R. Kelce. 2006.

- ^ Imperato-McGinley, Julianne; Zhu, Yuan-Shan (2002). "Gender and Behavior in subjects with Genetic Defects in Male Sexual Differentiation". Hormones, Brain, and Behavior. Elsevier Science. p. 304. ISBN 978-0128035924.

- ^ a b Development of sex cells Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine in Reproductive system, Body Guide. Adam.

- ^ Tilly JL, Niikura Y, Rueda BR (August 2008). "The Current Status of Evidence for and Against Postnatal Oogenesis in Mammals: A Case of Ovarian Optimism Versus Pessimism?". Biol. Reprod. 80 (1): 2–12. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.069088. PMC 2804806. PMID 18753611.

- ^ Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL (March 2004). "Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary". Nature. 428 (6979): 145–50. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..145J. doi:10.1038/nature02316. PMID 15014492. S2CID 1124530.

- ^ a b García-Rodríguez A, Gosálvez J, Agarwal A, Roy R, Johnston S (December 2018). "DNA Damage and Repair in Human Reproductive Cells". Int J Mol Sci. 20 (1): 31. doi:10.3390/ijms20010031. PMC 6337641. PMID 30577615.

- ^ Jensen, Christian Fuglesang S.; Østergren, Peter; Dupree, James M.; Ohl, Dana A.; Sønksen, Jens; Fode, Mikkel (September 2017). "Varicocele and male infertility". Nature Reviews Urology. 14 (9): 523–533. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2017.98. ISSN 1759-4820. PMID 28675168. S2CID 19357838. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ Genetic Conditions > Reproductive system. Archived 2008-12-04 at the Wayback Machine 2007. Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine.