Hotline Miami

| Hotline Miami | |

|---|---|

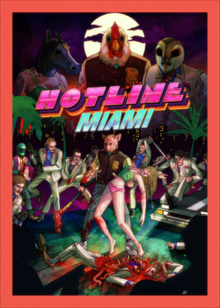

Cover art by Niklas Åkerblad | |

| Developer(s) | Dennaton Games[a] |

| Publisher(s) | Devolver Digital |

| Programmer(s) | Jonatan Söderström |

| Artist(s) | Dennis Wedin |

| Engine | GameMaker |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Top-down shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Hotline Miami is a top-down shooter video game developed by Dennaton Games and published by Devolver Digital. It was released in October 2012 for Windows, followed by versions for OS X, Linux, PlayStation 3, and PlayStation Vita in 2013, then a PlayStation 4 port in 2014. Hotline Miami is one of the most influential and successful independently developed games and considered both one of the best video games ever made and to have one of the best video game soundtracks. The game inspired other developers during the 2010s and contributed to the success of its publisher. By May 2015, it had sold 1.5 million copies.

Set in Miami in 1989, the game follows an unnamed silent protagonist—dubbed Jacket by fans—as he commits massacres against the local Russian mafia. As the game progresses, he is frequently interrogated for his actions, and slowly loses his grip on reality. In each level, the player must defeat every enemy through various means, ranging from firearms and melee weapons to more specific methods like knocking enemies out with doors. The player chooses one of several masks at the beginning of each level, each with unique abilities. At the end of the level, the player is given a score based on their performance, with higher scores granting the player new weapons and masks.

The game was the first released by Dennaton Games, composed of Jonatan Söderström and Dennis Wedin. Using a prototype Söderström made years prior, they developed Hotline Miami over nine months. Söderström programmed the game and wrote the narrative, while Wedin designed the graphics. Several artists contributed to the games soundtrack. Hotline Miami received generally positive reviews highlighting its gameplay, soundtrack, and atmosphere, though some criticized its controls.

A sequel, Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number, was released in March 2015. Hotline Miami and its sequel were rereleased as part of the localized Hotline Miami: Collected Edition in Japan that same year. Another compilation, the Hotline Miami Collection, released for Nintendo Switch in August 2019, and later for Xbox One, Stadia, PlayStation 5, and Xbox Series X/S.

Gameplay

[edit]

Hotline Miami is a top-down shooter game. It is set in Miami during the 1980s,[2] and is divided into nineteen "chapters".[3] At the beginning of each chapter, the player character "Jacket"[b] receives a message on his answering machine, instructing him to travel to a different part of Miami and kill all enemies at that location. The player is able to defeat their opponents through a variety of melee and ranged weapons, like crowbars and firearms.[2] The player can also knock out enemies with a door, use them as a human shield, or kick them against the wall. If an enemy is not immediately killed in an attack, the player can perform a specialized attack to finish them off.[6][7] Later stages in the game have the player take control of a different character, known as the Biker, who can only use knives.[8]

The player can be felled by a single attack, as well as enemies.[9] To compensate, the player is able to quickly restart the current stage after death, allowing them to rethink their strategy.[10][9] Different types of enemies appear throughout the game, like dogs[10] and boss characters.[6] The enemy AI is inconsistent, with reactions to attacks ranging from responding immediately to doing nothing.[3][9] The player is awarded points for each enemy they kill, with bonus points awarded based on the method of execution or the number of enemies killed in quick succession.[7] Aiming is predominantly done via a computer mouse, though the player can lock onto an enemy and not have to aim. On the PlayStation Vita, the functions of the mouse are shifted over to the touch screen, with locking onto enemies requiring the player to touch them on-screen.[11]

Before each chapter begins, the player can choose from a variety of animal masks,[4] which grant different abilities.[12] These attributes include the player's finishing moves being sped up and allowing them to see further.[6] At the end of each chapter, the player's total score is tallied and they are given a rating based on their performance.[13][14][6] The player's score is further adjusted based on their play style, which is given a classification like "coward" or "sadist".[13] High scores unlock new masks and weapons for the player to use.[14][6] The game also supports achievements, which are obtained by doing specific challenges like killing two enemies with one brick throw.[15]

Plot

[edit]In April 1989, Jacket receives a message on his answering machine and a package is delivered to his door containing a rooster mask. The package contains instructions advising Jacket to retrieve a briefcase from the Russian mafia at a metro station using violence. After carrying out the mission, Jacket continues to receive messages instructing him to conduct more massacres. After each massacre, Jacket visits a store or a restaurant where a man known as Beard[c] meets him and gives away free items such as pizza, films, and alcoholic beverages. During an assault on the estate of a film producer, Jacket rescues a girl and takes her to his apartment, nursing her back to good health and developing a romantic relationship with her. After this assault, Jacket is visited by three masked personas: Richard, Rasmus, and Don Juan, who question him for his actions. These encounters continue throughout the game. In another assault on a phone company, Jacket finds everybody dead except the Biker, who is attempting to access a computer, and the two fight to the death.[d]

As Jacket continues his massacres, his perception of reality becomes increasingly more surreal. Talking corpses begin appearing at Beard's places of work, and eventually Beard himself abruptly dies, being replaced by a bald man named Richter that offers Jacket nothing. After coming home one night, Jacket discovers his girlfriend murdered by Richter, who shoots Jacket and places him into a coma. In one final encounter with Richard, he tells Jacket that he will "never see the full picture". He then reveals to him that he was reliving the events of the past two months while comatose after being shot. After waking up, Jacket overhears that Richter has been arrested, and escapes the hospital in search of him. He storms Miami police headquarters, killing almost everyone inside and confronts Richter, who he discovered had also been receiving messages. Jacket spares his life[e] and steals the file on the police investigations of the killings before heading to a nightclub that the calls were tracked to, killing everyone there as well. He then heads to the Russian Mafia headquarters and confronts both leaders of the syndicate. After Jacket kills his personal bodyguard and injures his hands, one of the leaders "spares him the pleasure" and commits suicide. When Jacket confronts the other, he contemplates the things he did and allows Jacket to kill him without resistance. Afterwards, Jacket walks out onto a balcony, lights a cigarette, and throws a photo off of the balcony.

After completing the levels centered around Jacket, the player unlocks an epilogue centered around the Biker. Similarly to Jacket, the Biker has been receiving messages on his answering machine, and is dedicated to find their source. After the encounter with Jacket depicted earlier[d] and various interrogations, he finds the source of the messages to be 50 Blessings, a group operated by two janitors that attempt to undermine an alliance between the Soviet Union and the United States, which they view as "anti-American". They do this by ordering their operatives to commit numerous anti-Russian massacres. The game features two endings, with the full ending requiring the player to find puzzle pieces scattered throughout the game to crack 50 Blessings' password. If the player manages to crack the password, the Biker uncovers their secrets and political agenda. Without the password, the Biker is mocked and fails to discover the truth. In both endings, the player has the option to either kill or spare the janitors. After this, the Biker departs from Miami.[8][18]

Development

[edit]

Hotline Miami was developed by Dennaton Games, a duo composed of designer and programmer Jonatan Söderström and artist Dennis Wedin.[19][20] Söderström had previously developed numerous freeware indie games, such as the puzzle game Tuning,[21] which won the Nuovo Award at the Independent Games Festival in 2010.[22] Around this time, he developed numerous projects that were never completed. Among these was a top-down shooter titled Super Carnage, a game where the goal was to kill as many people as possible. He began work on the project in 2004 at the age of 18, but later abandoned the project after facing difficulties with developing the game's AI.[23]

Years later, Söderström met Wedin, a singer and keyboard player for synthpunk band Fucking Werewolf Asso. The two collaborated in making a promotional game based on the band, titled Keyboard Drumset Fucking Werewolf, as well as a separate project named Life/Death/Island. The latter became too much work for them to handle, and the project was abandoned. Following this, the two faced financial problems, and decided that their next game would be a commercial release. Wedin began searching through Söderström's unfinished projects, and came across the Super Carnage project.[23] With Wedin seeing potential in the concept after previously playing similar games like Gauntlet (1985) and Chaos Engine (1993),[24] the two began developing Hotline Miami.[23][25] The game was originally titled Cocaine Cowboy, named after the 2006 documentary Cocaine Cowboys.[23][25] Throughout development, Söderström posted updates on his Twitter account[26] and personal blog.[26][27]

The first playable version of the game was created within the first week of development after Söderström assembled the basics of the game, including a temporary soundtrack.[28] Although initially planned as a smaller project,[29] the game expanded after Vlambeer shared a demo with Devolver Digital, who then offered to publish it.[23][29] It was developed using the GameMaker engine over the course of nine months,[23] with the developers working twelve hours a day, six days a week.[30] Uncertain on whether or not the game would be successful, combined with developing the game with little to no budget, the team lost and regained motivation repeatedly. In an interview with Edge, Wedin described the development of the game as "fucking hard".[23] At one point during development, Wedin was hospitalized for two weeks due to depression caused by a break-up.[31] The version of GameMaker that the team was using to develop the game with was outdated, causing compatibility issues with newer operating systems. As a result, Dennaton faced numerous problems while developing the game, including many bizarre bugs reported by playtesters. Among these bugs was one that would cause the game to crash if certain printers were plugged into the player's computer.[23]

Design

[edit]When designing the gameplay, Wedin stated that they were designing a game that they wanted to play, initially being unconcerned with what an average consumer or a critic would think of it. According to him and Söderström, this design process allowed the team to determine what would "fit" the game or be liked by other players, based on whether or not they personally found it fun.[32] In a 2022 interview, the team said that they designed the game as an "arcade game first, and a reality simulator second".[33] When designing the game's AI, the team were conflicted on whether to make it more "believable" or to intentionally make it varied in behavior, but eventually chose the latter.[23] Wedin later stated that they "never wanted to do realistic behavior", and Söderström partially attributed the limitations of GameMaker to the varied behavior of enemies.[34] Some of the games mechanics, such as the ability to throw weapons at enemies, were initially coding errors that were turned into proper game mechanics.[35] The levels featuring the Biker were one of the last parts of the game to be developed, being created near the end of development.[36]

The game's writing was inspired by several movies that the team watched before starting development. Among these movies were the works of David Lynch, the superhero comedy film Kick-Ass (2010), the Cocaine Cowboys documentary, and Drive (2011).[23][37] Drive inspired the game's minimal dialogue and critique of violence, leading to the creation of the masked personas and their associated scenes.[23] In a June 2012 post on his personal blog, Söderström said that he was wanted the project to have an interesting, but "unintrusive" story that players could skip through if they wanted to.[26] Another inspiration was Gordon Freeman, the silent protagonist of the Half-Life series.[37] Söderström stated that Lynch's works left the largest influence on the game overall.[23] Some of the game's characters were based on real people, with Beard being based on artist Niklas Åkerblad,[38] a friend of the developers and owner of the apartment the two developed the game in,[39] and the janitors being the developers' self-inserts.[40]

The game's graphics were created by Wedin,[41] using pixel art[23] with a high-contrast colour palette.[42] The first assets created for the game, a player sprite and an enemy sprite, were created by Wedin within the first few days of development during a weekend.[43] While the team felt that the game's violent nature could cause controversy, the team believed the decision to use pixel art would mediate any potential problems. Wedin stated that, while he thought games that used realistic 3D graphics were often singled out when a real-world attack took place, Hotline Miami's graphics kept the game "out of the spotlight."[23] When looking for artists to design the game's box art, the team initially looked for artists who worked on older horror films. When they were unable to agree on who should design it, Åkerblad offered to create the box art himself, and made it in about three days.[39]

Music

[edit]Creating Hotline Miami's soundtrack was a focus of the developers, with both developers viewing it as an important part of the game. Their goal was to create a soundtrack that did not "sound like game music", but instead sounded like a movie soundtrack.[25][44] After failing to obtain the licenses for a temporary soundtrack they put together early in the game's development, the team began searching Bandcamp for tracks that were free to download;[25] according to Söderström, the team listened to up to two thousand tracks.[44] Some artists like M.O.O.N. were found through this process, while other artists like Scattle contacted Dennaton themselves after seeing blog posts of the game's development. Tracks from M.O.O.N. were directly added to the game, while Scattle was tasked with composing original music specifically for the game using Renoise.[25] Other artists featured in the game include Coconuts, Sun Araw,[45] and Perturbator.[46] Artists such as Åkerblad (under the alias "El Huervo") made direct contributions themselves.[38] The final soundtrack consists of 22 tracks[47] of several different styles, ranging from those that primarily use bass and drums including the aforementioned "Hydrogen", to more up-beat pop tracks such as "Miami Disco" by Perturbator.[48]

Release

[edit]Hotline Miami was first announced through Söderström's personal blog on 3 July 2012. A teaser trailer was also released at the same time.[27] The game was later showcased at the A Maze Indie Connect festival,[30] and again later at a Rezzed exposition in Brighton.[23] Reception towards the game at A Maze was mixed,[30] but was later praised by attendees at Rezzed. It was most played game at Rezzed that year, and won the Game Of The Show award; Tom Bramwell of Eurogamer described the game as the "best example of the sort of game we invented the show for."[49] For the game's promotion, Dennaton purchased a phone number in the Miami area that allowed people to leave messages that would later be used in a trailer.[50] Hotline Miami released on Steam on 23 October 2012.[51] Support for MacOS and Linux released on 19 March and 9 September respectively in 2013.[52][53]

In November 2012, an update for the game was released that patched numerous bugs, added support for gamepads, and made minor graphical and gameplay adjustments. This update also added a bonus level, "Highball", which has no relation to any other level in the game.[54] Around this time, Söderström created numerous patches for pirated versions of Hotline Miami after several users of The Pirate Bay reported issues with the game. He stated that he wanted players to "experience the game the way it's meant to be experienced", regardless of whether or not they obtained it through legitimate means.[55] The game's soundtrack was released via Steam in January 2013;[56] a physical release, with all of the tracks pressed across three vinyls, was released in 2016 through Laced Records. It was a limited release, with only 5,000 copies made, and was funded by a Kickstarter campaign that raised over $75,000.[47]

Versions of Hotline Miami for PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Vita, developed by Abstraction Games, released on 25 July 2013 in North America, and a day later in Europe. These releases supported cross-buy, allowing players who purchased the game on one platform to receive it on the other.[1][57] These ports also added a bonus mask and leaderboards.[57] A version for PlayStation 4, also supporting cross-buy, released on 19 August 2014.[58][59] A Japan-localized compilation, featuring Hotline Miami alongside its sequel Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number (2015), titled Hotline Miami: Collected Edition, was released in June 2015.[60] On 19 August 2019, Hotline Miami and Hotline Miami 2 were re-released as part of the Hotline Miami Collection for Nintendo Switch.[61] The Hotline Miami Collection was later ported to Xbox One and Stadia on 7 April and 22 September 2020 respectively,[62][63] and PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S on 23 October 2023.[64]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | (PC) 85/100[65] (PS3) 87/100[65] (Vita) 85/100[65] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Eurogamer | 10/10[15] |

| Game Informer | 7.75/10[2] |

| GameSpot | 8.5/10[6] |

| GamesRadar+ | 4/5[3] |

| IGN | 8.8/10[14] |

| PC Gamer (US) | 86/100[10] |

| Polygon | 8.5/10[7] |

| VideoGamer.com | 9/10[66] |

| PopMatters | 9/10[67] |

According to review aggregator Metacritic, Hotline Miami received generally positive reviews from critics. On that platform, it holds an aggregated score of 85 per cent based on 51 reviews for the PC version, 87 per cent based on 19 reviews for the PlayStation 3 version, and 85 per cent based on 27 reviews for the PlayStation Vita version.[65]

Several reviewers praised the gameplay of Hotline Miami. Many found the game to be enjoyable, considering it addicting despite frequent death.[f] Polygon's Chris Plante considered playing the game to be similar to playing a sport, stating that the game compensated for being repetitive by allowing the player to restart quickly, and found the game to be addicting.[7] Graham Smith of PC Gamer shared similar thoughts, writing that the game was designed to "inspire a fever," and that "once you're hooked, it's easy to get carried away." He also wrote that, even when putting the game's addicting nature aside, the game was still "tight" and "efficient".[10] Phill Cameron of VideoGamer.com described the game as "five seconds of action that you can lose yourself in for five hours."[66] Danny O'Dwyer of GameSpot was indifferent, though he wrote that the times Hotline Miami did "get it wrong" were "deeply frustrating". He specifically pointed out the game's boss fights, which he believed had arbitrary methods on how to defeat them.[6]

Some criticisms were made towards Hotline Miami's controls,[g] with Ben Reeves of Game Informer writing that the controls inhibited what was otherwise "one of the most creative indie titles of the year."[2] Eric Swain of PopMatters believed that the PlayStation 3 version's control differences made the game easier, and consequentially made players "miss out" on the original game's intended feel.[67] Giancarlo Saldana of GamesRadar+ felt that the game's controls on the PlayStation 3 took some time to get used to, and that playing it on computer was more ideal, but that players could get used to them.[3]

The game's narrative was well received,[h] with Reeves describing it as "perfectly [placing] you inside the mind of a serial killer."[2] Saldana described the game as an "introspective journey into the violence of video games", and that it had a "daring narrative style" that gained the attention of players.[3] Plante wrote that game had "more to say about our fascination with violence" than other titles, describing Hotline Miami as an exceptional game not due to its violence, but because it had a "reason" to be violent.[7] While Smith felt that the game's narrative was lacking in depth and no justification was given for the violence, he believed that too many other video games offered cliché reasons for violence, and described it as a "relief".[10] Cameron wrote that the game missed an "opportunity to make a point" and never properly explained why so many people were being killed, instead allowing the player to reflect on themselves.[66] The game's visual design was also well received, often being discussed alongside Hotline Miami's narrative and sound design.[6][14][3]

The game's soundtrack was praised, with several critics highlighting it as one of the best aspects of the game.[i] Reeves described the soundtrack as doing a "phenomenal job",[2] and Saldana felt that it was "executed perfectly".[3] O'Dwyer described it as "outstanding" and fitting well with the game's visual design, believing that both combined were able to allow the player to look past the game's flaws.[6] Charles Onyett of IGN wrote that the soundtrack "[meshes] perfectly" with the rest of the game.[14] Eurogamer's Tom Brawell shared similar thoughts as O'Dwyer and Onyett, feeling that while the soundtrack was less impactful on its own, it tied in well with the rest of the game.[15]

Sales

[edit]Hotline Miami sold over 130,000 units within the first seven weeks of its initial release.[68] By the time the game's PlayStation 3 version was announced in February 2013, the game had sold 300,000 units. According to Anthony John Agnello of Digital Trends, the game's commercial success up to that point was the reason Sony wanted Hotline Miami on the platform, helping the company "maintain its reputation" as a "purveyor" of indie titles after the success of Journey (2012).[69] When Hotline Miami released on PlayStation Vita, it became the platform's best selling game of the month within six days, despite releasing near the end of the month.[70] By May 2015, it had sold over 1.5 million units on all platforms.[71]

Awards

[edit]A month before release, the game won the "Most Fantastic" award at the 2012 Fantastic Arcade festival in Austin.[72] At the end of the year, Hotline Miami was nominated for several awards by IGN at its "Best of 2012" awards,[73][74] including "Best Overall Game".[75] It was also nominated for "Best PC Action Game",[74] "Best PC Story",[76] "Best PC Game",[77] "Best Overall Action Game",[78] and "Best Overall Music",[79] It won the award for "Best PC Sound".[73] PC Gamer selected Hotline Miami as the recipient of its "The Best Music of the Year 2012" award.[80] At the 2012 Machinima's Inside Gaming Awards, the game received the "Most Original Game" award.[81][82] It was nominated for several awards at the Independent Games Festival in 2013, including the Seumas McNally Grand Prize, as well as the Excellence in Audio and Excellence in Design awards.[83] Several publications considered Hotline Miami to be one of the best games released in 2012. These publications include Kill Screen,[84] Paste,[85] Ars Technica,[86] Wired,[87] The Guardian,[88] and VentureBeat.[89]

Themes and analysis

[edit]Hotline Miami advocates an anti-violence message through making the player feel guilt for their in-game massacres.[90][46] Some found this to be done through the utilization of upbeat music and its score system to motivate the player. As the game is fast-paced, the player may enter a state where they're focused exclusively on their inputs and become desensitized to the actions they are committing.[8][90] Pitchfork's Nina Corcoran believed that the game's upbeat soundtrack contributed to this by ratcheting the players anxiety and increasing their focus, while also desensitizing them to the glorified violence.[44] At the end of each level, the upbeat music is replaced with ambience while the player exits the building, with the remains of enemies scattered across the floor.[8] NME's Dom Peppiatt compared Hotline Miami's anti-violence commentary to be similar to A Clockwork Orange and American Psycho. He wrote that the game made players think about where the "line between fiction and reality blurs", and made them reconsider the violence present within video games as a whole.[46]

Each of the game's masked personas serve a specific purpose in their encounters. Richard is often inquisitive, Don Juan is generally passive and friendly, while Rasmus is aggressive. They also each have a unique color assigned to them reflecting their personality, with Richard's being yellow, Don Juan's being blue, and Rasmus' being red. Each interrogates the player uniquely; Don Juan's dialogue includes lines like "knowing oneself means acknowledging one's actions," while Richard is more upfront, asking "do you like hurting other people?"[91] Additionally, the masked figures never reveal any details about the identity of Jacket, instead teasing the player directly.[92] The masked figures also foreshadow upcoming events in the game's narrative, such as hinting at the murder of Jacket's girlfriend.[8][91]

Luca Papale and Lorenzo Fazio suggested that the contrasting behaviors of the masked figures may represent dissociative identity disorder in Jacket.[4] Similar thoughts were written by Marco Caracciolo of the University of Groningen, who believed that the masked personas to possibly be "projections of Jacket's disturbed psyche." He additionally wrote that the game's plot is "destined not to make any sense", citing the behavior of the masked figures as well as the contradictions between the perspectives of Jacket and the Biker.[92] Papale and Fazio considered Jacket to be the first example of a "meta-avatar",[93] a type of character with the ability to cause players to rethink their own actions and cause instability within their identity.[94] This type of character was compared to Doomguy from the DOOM series and Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series, who were seen as examples of "mask digital prosthesis", referring to the overlapping of identities between a player and a game's protagonist.[4]

Legacy

[edit]Retrospective commentary has considered Hotline Miami to be one of the most influential indie games, as well as one of the most critically and financially successful.[j] Its success inspired many to begin developing video games,[95] contributing to an increase in indie game releases throughout the 2010s.[44] Many of these games include similar narrative themes, gameplay mechanics, or soundtracks to Hotline Miami.[95][44][48] Games influenced by Hotline Miami continued to be made over a decade after its release,[97] ranging from indie games to titles made by larger, big-budget studios like The Last of Us Part II (2020).[95] The game's soundtrack has also been influential separately from the game itself,[k] helping popularize the synthwave music genre and leading to the mainstream success of the artists involved.[98][99] The game is often attributed to the success of Devolver Digital, which has since become one of the most successful indie game publishers.[96][99]

Hotline Miami's narrative and handling of violence have been considered by many journalists to be influential within the video game industry,[90][95][100] with an impact lasting into the 2020s.[95] In a 2019 retrospective article from Vice's Cameron Kunzelman, he described Hotline Miami's anti-violence themes as an "emblem of a forgotten regime" alongside other titles released at the time like Spec Ops: The Line (2012). He felt that since Hotline Miami's release, more video games had started treating violence as a method of demonstrating "seriousness" without a proper justification. He specifically highlighted a trailer for The Last of Us Part II, as well as how some of Hotline Miami's more serious dialogue had become internet memes. He also believed that video games were due for "another shift" in how to treat violence.[90] Chris Tapsell of Eurogamer echoed similar thoughts as Kunzelman in 2024, describing Hotline Miami as the video game industry's "coming-of-age moment" and a point of self-reflection.[100]

In 2023, The Verge's Aleksha McLoughli described Hotline Miami as the "gold standard" for an indie game. He believed that the game was the best in its sub-genre, with no other games being able to compare to its success.[95] Nina Corcoran of Pitchfork shared similar thoughts, and believed that the game was designed by Dennaton to be "incredibly replayable" several years later.[44] In a 2022 article published by The Ringer, Lewis Gordon described Hotline Miami as a game that "[stretched] the boundaries" of the video game industry, as one of the more "warmly-regarded" indie games.[96] Christopher Cruz of Rolling Stone described Hotline Miami as a "titan of indie gaming", one with an "impact [that] has reached far and wide".[48] The game has also garnered a cult following.[101]

In the years since its release, Hotline Miami has often been considered to be one of the best video games ever made by the editorial teams of several magazines and media outlets.[l] These include the teams of GamesRadar+,[102] Slant Magazine,[103][104][105] Hardcore Gaming 101,[106] Stuff.tv,[107] Popular Mechanics,[109] GamesTM,[110][111] USA Today,[108] and Sports Illustrated.[112] The game has considered one of the best PC games by the editorial teams of PC Gamer and Rock, Paper, Shotgun,[113][114] and one of the best PlayStation Vita games by Digital Trends and GamesRadar+.[115][116] It was also listed in the book 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die.[117] Its soundtrack has received similar praise, with writers from Paste, GameSpot, PCMag and VG247 considering Hotline Miami's soundtrack to be one of the best from a video game.[118]

Sequel and franchise

[edit]

Shortly after the games release, Dennaton began developing downloadable content for it to expand upon its story, as well as add a level editor.[119] When the proposed length of the project surpassed that of the main game, it became its own standalone title. Announced ten days after the release of Hotline Miami,[120] Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number was released on 10 March 2015.[121] The game expanded upon the universe of the original, introducing new characters and focusing on the background and aftermath of Jacket's massacres. It also served as the conclusion of the series' story.[5] Due to differences in gameplay and level design, Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number was not received as well as the first game, with critic reviews being generally lower[97] and player feedback being divisive.[122] Both games were included in the Hotline Miami Collection, which first released in August 2019.[61] As of 2022, both games in the series have sold over five million units combined across several platforms.[96]

In 2016, an eight-part comic book series based on the series, Hotline Miami: Wildlife, was announced. It was released digitally over the course of several months and follows a protagonist named Chris, depicting events not considered canon to the main Hotline Miami story.[123] A parody of the game, "Hotline Milwaukee", is included as part of Devolver Bootleg, a 2019 compilation of parodies of numerous games published by Devolver Digital.[124] Jacket has appeared as a playable character in other games, such as Payday 2 (2013) and Dead Cells (2019).[125][126] Several fan games based on the series have been created, often incorporating elements from other games such as Team Fortress 2 (2007) and Half-Life (1998).[127][128] Among these was Midnight Animal, a fan game that would have incorporated elements from the Persona series, but was cancelled by 2019.[129]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Abstraction Games developed the console ports.[1]

- ^ Jacket is a fan-assigned name to an otherwise unnamed protagonist.[4] The name was adopted by Dennaton themselves later on.[5]

- ^ Similarly to Jacket, Beard goes unnamed in the game. In Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number, the character is known as The Soldier.[16]

- ^ a b Jacket and the Biker fight each other twice, with both times having a different outcome.[8]

- ^ While the player has the choice to either kill or spare Richter,[17] he is seen alive in the games sequel.[16]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[2][6][15]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[2][66][67]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[3][2][14][7]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[66][15][3][6][14]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[95][96][97][48]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[98][48][44][99]

- ^ Attributed to several sources[102][103][104][105][106][107][108]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Tach, Dave (19 February 2013). "Hotline Miami headed to PlayStation 3 and Vita this spring". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Reeves, Ben (5 November 2012). "Hotline Miami – a demented tour through the mind of a killer". Game Informer. GameStop. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Giancarlo, Saldana (26 June 2013). "Hotline Miami review". GamesRadar+. Future US. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Papale & Fazio 2018, p. 271.

- ^ a b "The making of Hotline Miami 2". PC Gamer. Future US. 2 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k O'Dwyer, Danny (4 October 2013). "Hotline Miami review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Plante, Chris (25 October 2012). "Hotline Miami review: American psycho". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ismail, Rami (29 October 2012). "Why Hotline Miami is an important game". Game Developer. Informa. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Bramble, Simon (21 December 2017). "Hotline Miami's cleverest surprise is that it's not a shooter - it's a puzzle game". GamesRadar+. Future US. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Graham (1 November 2012). "Hotline Miami review". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Mautlef, Jeffrey (26 June 2013). "How Hotline Miami plays on PS3 and Vita". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Brey, Clarke & Wang 2020, p. 34.

- ^ a b Vujanov 2021, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Onyett, Charles (26 October 2012). "Hotline Miami review – 147 crazy kills". IGN. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Bramwell, Tom (23 October 2012). "Hotline Miami review – call now to avoid disappointment". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b Cook, Dave (17 April 2015). "The story of Hotline Miami 2 explained". Vice. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Dennaton Games. Hotline Miami. Devolver Digital. Level/area: "Assault".

- ^ Vujanov 2021, p. 5.

- ^ Devore, Jordan (1 July 2013). "Hotline Miami: From Super Carnage to indie success story". Destructoid. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 7:10.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (1 October 2012). "Blood and pixels on the beach: the story of Hotline Miami". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 4 September 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "2010 Independent Games Festival winners & finalists". Independent Games Festival. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "The making of: Hotline Miami". Edge. Future US. 30 June 2013. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 5:00.

- ^ a b c d e Valjalo, David (21 January 2013). "Behind the sounds: Hotline Miami and FTL". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Söderström, Jonatan (15 June 2012). "Quick update". Cactussquid.com // GAME DESIGN. Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ a b Söderström, Jonatan (3 July 2012). "Hotline Miami - announcement trailer". Cactussquid.com // GAME DESIGN. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 12:10.

- ^ a b Noclip 2022, 5:30.

- ^ a b c Procter, Lewie (22 August 2012). "Cactus on Hotline Miami: "I'm pretty tired of crappy games that don't really want to do anything special"". PCGamesN. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Conditt, Jessica (4 April 2018). "It's time to talk about mental illness in indie development". Engadget. AOL. Archived from the original on 20 April 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 7:35.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 9:02.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 9:20.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 9:48.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 13:12.

- ^ a b "We ask indies: Cactus, creator of Hotline Miami and tons of other weird titles". Game Developer. Informa. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Hotline Miami cover artist on his distinct visual style, music, and Beard". Kotaku Australia. G/O Media. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b Hester, Blake (27 August 2015). "How some of the game industry's best teams make box art". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Vujanov 2021, p. 7.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 7:12.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 6:53.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 5:20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Corcoran, Nina (8 March 2023). "Hotline Miami and the rise of techno in ultra-violent video games". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 27 June 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Francis, Tom (1 December 2012). "Hotline Miami interview: Dennaton Games on creating carnage to delight and disgust". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Peppiatt, Dom (9 May 2022). "10 years later, the 'Hotline Miami' OST remains the perfect accompaniment for introspective, psychedelic ultraviolence". NME. Archived from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Timothy J., Seppala (13 March 2016). "The pulsing 'Hotline Miami' soundtrack gets physical". Engadget. AOL. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Cruz, Christopher (27 May 2024). "The 25 best video game soundtracks of all time". Rolling Stone Australia. Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Bramwell, Tom (9 July 2012). "Rezzed 2012: Eurogamer's Game of the Show is Hotline Miami". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Zimmerman, Conrad (11 December 2012). "Hotline Miami checks its voicemail". Destructoid. ModernMethod. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Fletcher, JC (8 October 2012). "Hotline Miami makes housecalls October 23". Joystiq. AOL. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Tach, Dave (19 March 2013). "Hotline Miami released for Mac". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Game update patch notes - September 9, 2013". steamcommunity.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Onyett, Charles (5 November 2012). "Hotline Miami gets controller support". IGN. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Hotline Miami creator helps pirates play his game". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. 26 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Savage, Phil (25 January 2013). "Hotline Miami soundtrack now on Steam; plus the game is half price". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Hotline Miami launching on PSN next week". Digital Spy. Hearst Communications. 21 June 2013. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Karmali, Luke (24 March 2014). "Hotline Miami headed to PS4 With cross-buy support". IGN. IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Parker, Fork (11 August 2014). "Hotline Miami hits PS4 August 19th". PlayStation Blog. Sony Computer Entertainment. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ "ピーッ。新しいメッセージは1件です——「衝撃の問題作『ホットライン マイアミ』の1作目と2作目がセットになって日本上陸! 『ホットライン マイアミ Collected Edition』が6月25日発売決定!!!!」【先出し週刊ファミ通】". Famitsu (in Japanese). 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Samit (19 August 2019). "Hotline Miami Collection launching today on Nintendo Switch". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Romano, Sal (7 April 2020). "Hotline Miami Collection now available for Xbox One". Gematsu. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ "Take back the town with Hotline Miami, arriving Sept. 22 on Stadia". Stadia Community Blog. 18 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Andy (23 October 2023). "The Hotline Miami games have been released for PS5 and Xbox Series". Video Games Chronicle. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Hotline Miami". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Cameron, Phill (24 October 2012). "Hotline Miami review". VideoGamer.com. Candy Banana. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Swain, Eric (5 August 2013). "Hotline Miami (PS3)". PopMatters. PopMatters Media. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Purchese, Robert (11 December 2012). "The Hotline Miami sales story, and more". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Agnello, Anthony (19 February 2013). "Hotline Miami slaughters its way onto Sony's PS Vita and PlayStation 3". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Armitage, Hugh (9 July 2013). "Hotline Miami tops PS Vita June chart". Digital Spy. Hearst Communications. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Futter, Mike. "The story behind Hotline Miami is one of no pants and countless deaths". Game Informer. GameStop. Archived from the original on 20 May 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ McElroy, Griffin (25 September 2012). "Hotline Miami wins 'Most Fantastic' award during Fantastic Arcade 2012". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 16 September 2024. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Best PC Sound – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Best PC Action Game – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Best Overall Game – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Best PC Story – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Best PC Game – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Best Overall Action Game – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Best Overall Music – Best of 2012". IGN. IGN Entertainment. 5 December 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Davies, Marsh (24 December 2012). "The Best Music of the Year 2012: Hotline Miami". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Good, Owen (9 December 2012). "Don't like the winners from the 2012 VGAs? Get a second opinion from Machinima's IGAs". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Farokhmanesh, Megan (9 December 2012). "Inside Gaming Awards winners include Halo 4, Fez". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Hillier, Brenna (7 January 2013). "Hotline Miami, Cart Life, Little Inferno headline IGF Award finalists". VG247. Future US. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Kill Screen's top ten games of 2012". Kill Screen. 2 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 December 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Marin, Garrett (20 December 2012). "The 30 best videogames of 2012". Paste. Archived from the original on 19 May 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (29 December 2012). "Ars Technica's 2012 Games of the Year". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "Indie passion fuels the 10 best games of 2012". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Stuart, Keith (19 December 2012). "Top 25 games of 2012: 15-11". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (21 December 2012). "The best games of 2012". VentureBeat. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kunzelman, Cameron (2 August 2019). "'Hotline Miami' showed the futility of ultra-violence as critique". Vice. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b Vujanov 2021, p. 6.

- ^ a b Caracciolo 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Papale & Fazio 2018, p. 270.

- ^ Papale & Fazio 2018, p. 273.

- ^ a b c d e f g Argüello, Diego Nicolás (26 October 2022). "'Hotline Miami's ultra-violence has influenced games for a decade". The Verge. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Gordon, Lewis (25 October 2022). "Ten years later, Hotline Miami remains a queasy, ultraviolent classic". The Ringer. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b c McLoughlin, Aleksha (18 April 2023). "Over 10 years later, Hotline Miami remains the indie games gold standard". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b Iwaniuk, Phil (4 October 2017). "How synthwave music inspired games to explore a past that never existed". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c C, Luiz H. (23 February 2022). "Hotline Miami – Celebrating a decade of the masterful murder simulator". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on 7 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Eurogamer Staff (3 September 2024). "The Eurogamer 100". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Tapsell, Chris (28 November 2019). "Games of the decade: Hotline Miami - filth, fetish, and the only video game parable". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 23 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ a b "The 100 best games of all-time". GamesRadar+. Future US. 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Slant. 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015.

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Slant. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b "The 100 Best Video Games of All Time". Slant. 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b "HG101 Presents: The 200 best video games of all time". Hardcore Gaming 101. 5 December 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Best Games Ever: the 20 greatest games of all time". Stuff.tv. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b "The 100 best video games of all time, ranked". USA Today. 10 September 2022. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Moore, Bo (16 June 2014). "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Communications. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ "100 Greatest Games of All Time". GamesTM (Special issue). September 2015.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Games of All Time". GamesTM (200). May 2018.

- ^ Georgina Young (27 January 2023). "The best 100 games of all time, ranked". Sports Illustrated. Minute Media. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Castle, Katharine (11 November 2021). "The RPS 100: our top PC games of all time (50-1)". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "The top 100 PC games". PC Gamer. Future US. 14 October 2024. Archived from the original on 21 October 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Gurwin, Gabe; Lennox, Jesse (14 March 2020). "The best PS Vita games of all time". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 8 December 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "The 25 best PS Vita games of all time". GamesRadar+. Future US. 26 June 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Tony Mott, ed. (2013). 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die. Universe Publishing. p. 943. ISBN 978-1844037667.

- ^

- Martin, Garrett (5 May 2020). "The best videogame Soundtracks of All Time". Paste. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- Petite, Steven (22 January 2021). "Best video game soundtracks: where to stream them". GameSpot. Red Ventures. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- Jensen, K. Thor (25 August 2022). "The 25 best video game soundtracks ever". PCMag. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- Raynor, Kelsey (1 September 2023). "The best video game soundtracks to revisit in 2023". VG247. Future US. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (16 November 2012). "The creators of Hotline Miami on inspiration, storytelling and upcoming DLC". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (26 November 2012). "Hotline Miami sequel announced". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Crossley, Rob (25 February 2015). "Hotline Miami 2 release date confirmed for PS4, Vita, PC". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Noclip 2022, 20:30.

- ^ Gurwin, Gabe (6 July 2016). "A brand new Hotline Miami comic series launches today". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Reuben, Nic (12 June 2019). "Wot I think: Devolver Bootleg". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Nunneley-Jackson, Stephany (25 February 2015). "Payday 2 packs based on Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number coming". VG247. Future US. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Stanton, Rich (7 November 2022). "Dead Cells adds the Hotline Miami chicken dude, who crits stunned enemies with a bat". PC Gamer. Future US. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Maiberg, Emanuel. "Half-Life meets Hotline Miami in this fan game mashup". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Smith, Graham (23 July 2022). "This free fangame blends Hotline Miami with Team Fortress 2". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

- ^ Reuben, Nic (13 August 2019). "The messy story behind the Hotline Miami mod that never was". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Vujanov, Jovana (2021). "The Emptiness of Hardcore: Consuming Violence in Hotline Miami". Polish Journal for American Studies. 15 (15 (Autumn 2021)): 303–315. doi:10.7311/PJAS.15/2/2021.09.

- Papale, Luca; Fazio, Lorenzo (2018). "Player Identity and Avatars in Meta-Narrative Video Games: A Reading of Hotline Miami". Springer Science+Business Media. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11318. pp. 270–274. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04028-4_28. ISBN 978-3-030-04027-7. Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- Caracciolo, Marco (2014). "Unknowable Protagonists and Narrative Delirium in American Psycho and Hotline Miami: A Case Study in Character Engagement Across the Media". Central and Eastern European Online Library (9): 189–207. Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- Brey, Betsy; Clarke, M.J.; Wang, Cynthia (2020). Indie Games in the Digital Age. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1501356438.

- Noclip (17 January 2022). Hotline Miami creators break down its design & legacy. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2024 – via YouTube.

External links

[edit]- Hotline Miami

- 2012 video games

- Action games

- Alternate history video games

- Android (operating system) games

- Dennaton Games games

- Devolver Digital games

- GameMaker games

- Indie games

- Linux games

- MacOS games

- Neo-noir video games

- Nintendo Switch games

- Organized crime video games

- PhyreEngine games

- PlayStation 3 games

- PlayStation 4 games

- PlayStation 5 games

- PlayStation Network games

- PlayStation Vita games

- Psychological thriller video games

- Single-player video games

- Stadia games

- Top-down video games

- Video games adapted into comics

- Video games developed by Jonatan Söderström

- Video games developed in Sweden

- Video games set in 1989

- Video games set in Florida

- Video games set in Miami

- Windows games

- Works about the Russian Mafia

- Xbox One games

- Xbox Series X and Series S games