Hosea Williams

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Hosea Williams | |

|---|---|

Williams in 1966 | |

| Born | Hosea Lorenzo Williams January 5, 1926[1] Attapulgus, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | November 16, 2000 (aged 74)[2][3] Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lincoln Cemetery (Atlanta, Georgia). |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1956–2000 |

| Known for | Activist during the civil rights movement |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7, including Elisabeth Omilami |

| Family | Porsha Williams (granddaughter) |

Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He was considered a member of famed civil rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King Jr.'s inner circle. Under the banner of their flagship organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King depended on Williams to organize and stir masses of people into nonviolent direct action in myriad protest campaigns they waged against racial, political, economic, and social injustice. King alternately referred to Williams, his chief field lieutenant, as his "bull in a china shop" and his "Castro." Vowing to continue King's work for the poor, Williams is well known in his own right as the founding president of one of the largest social services organizations in North America, Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless. His famous motto was "Unbought and Unbossed."[a]

Background

[edit]Williams was born in Attapulgus, Georgia, a small city in the far southwest corner of the state in Decatur County. Both of his parents were teenagers committed to a trade institute for the blind in Macon. His mother ran away from the institute upon learning of her pregnancy. At the age of 28, Williams stumbled upon his birth father, "Blind" Willie Wiggins, by accident in Florida.[4] His mother died during childbirth when he was 10 years old. He and his older sister, Theresa, were raised by his mother's parents, Lelar and Turner Williams. Williams was run out of town by a lynch mob at the age of 13 for allegedly consorting with a white girl.[5]

Williams served with the United States Army during World War II in an all-African-American unit under General George S. Patton Jr. and advanced to the rank of Staff Sergeant. He was the only survivor of a Nazi bombing, which left him in a hospital in Europe for more than a year and earned him a Purple Heart.[6] Upon his return home from the war, Williams was savagely beaten by a group of angry whites at a bus station for drinking from a water fountain marked "Whites Only." He was beaten so badly that the attackers thought he was dead. They called a black funeral home in the area to pick up the body. En route to the funeral home, the hearse driver noticed Williams had a faint pulse and was barely breathing, but was still alive. There were no hospitals in the area that would serve blacks, even in the case of a medical emergency; the trip to the nearest veterans' hospital was well over a hundred miles. Williams spent more than a month hospitalized recuperating from injuries sustained in the attack.

Of the attack, Williams was quoted as saying, "I was deemed 100 percent disabled by the military and required a cane to walk. My wounds had earned me a Purple Heart. The war had just ended and I was still in my uniform for god's sake! But on my way home, to the brink of death, they beat me like a common dog. The very same people whose freedoms and liberties I had fought and suffered to secure in the horrors of war ... they beat me like a dog ... merely because I wanted a drink of water." He went on to say, "I had watched my best buddies tortured, murdered, and bodies blown to pieces. The French battlefields had literally been stained with my blood and fertilized with the rot of my loins. So at that moment, I truly felt as if I had fought on the wrong side. Then, and not until then, did I realize why God, time after time, had taken me to death's door, then spared my life ... to be a general in the war for human rights and personal dignity." After the war, he earned a high school diploma at the age of 23, then a bachelor's degree and a master's degree (both in chemistry) from Atlanta's Morris Brown College and Atlanta University (present-day Clark Atlanta University). Williams was a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity. Williams' birthday coincided with the anniversary of the death of one of that organization's most prominent members, George Washington Carver. After college, Williams worked for the United States Department of Agriculture as an analytical chemist in Savannah from 1952 until 1963, in its Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine chemistry laboratory where his work focused on insecticide analysis and he would develop a method of pyrethrin determination. In 1976, Williams founded the Southeast Chemical Manufacturing and Distributing Company, which manufactured and sold specialized cleaning supplies. Williams would go on to found three other chemical companies and a bonding company.

Early civil rights activism

[edit]

Williams first joined the NAACP, during which time he was a leader in the Savannah Protest Movement. However, he later became a leader in the SCLC along with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, James Bevel, Joseph Lowery, and Andrew Young, among many others. He played an important role in the demonstrations in St. Augustine, Florida, that some claim led to the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.[7]

While organizing during the 1965 Selma Voting Rights Movement he also led the first attempt at a 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, and was tear gassed and beaten severely. On March 7, 1965 – a day that would become known as "Bloody Sunday" – Williams and fellow activist John Lewis led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. At the end of the bridge, they were met by Alabama State Troopers who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with night sticks. Repercussions from the "Bloody Sunday" attempt led to the other great legislative accomplishment of the movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After leaving the SCLC, Williams played an active role in supporting strikes in the Atlanta, Georgia, area by black workers who had first been hired because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[7]

Political career

[edit]In the 1966 gubernatorial race, Williams opposed both the Democratic nominee, segregationist Lester Maddox, and the Republican choice, U.S. Representative Howard Callaway. He challenged Callaway on myriad issues relating to civil rights, minimum wage, federal aid to education, urban renewal, and indigent medical care. Williams claimed that Callaway had purchased the endorsement of the Atlanta Journal. Ultimately, after a general election deadlock, Maddox was elected governor by the state legislature.[8]

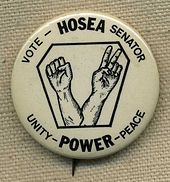

In 1972, Williams ran in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate seat formerly held by the late Richard Russell, Jr. He polled 46,153 votes (6.4 percent). The nomination and the election went to fellow Democrat Sam Nunn. In 1974, Williams was elected to the Georgia Senate where he served five terms as a Democrat, until 1984. In 1985, he was elected to the Atlanta City Council, serving for five years, until his election in 1989 when he ran for Mayor of Atlanta but lost to Maynard Jackson. That same year Williams successfully campaigned for a seat on the DeKalb County, Georgia County Commission which he held until 1994. Williams supported former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter for president in 1976 but surprised many black civil rights figures in 1980 by joining Ralph Abernathy and Charles Evers in endorsing Ronald Reagan. By 1984, however, he had soured on Reagan's policies, and returned to the Democrats to support Walter F. Mondale.

On January 17, 1987, Williams led a "March Against Fear and Intimidation" in Forsyth County, Georgia, which at the time (before becoming a major exurb of northern metro Atlanta) had no non-white residents. The ninety marchers were assaulted with stones and other objects by several hundred counter-demonstrators led by the Nationalist Movement and Ku Klux Klan. The following week 20,000, including senior civil rights leaders and government officials marched. Forsyth County began to slowly integrate in the following years with the expansion of the Atlanta suburbs.[citation needed] In 1971, Hosea Williams founded a non-profit foundation, Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless, widely known in Atlanta for providing hot meals, haircuts, clothing, and other services for the needy on Thanksgiving, Christmas, Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Easter Sunday each year. Williams' daughter Elizabeth Omilami serves as head of the foundation. In 1974, Williams organized the International Wrestling League (IWL), based in Atlanta, with Thunderbolt Patterson serving as president. Among other entrepreneurial endeavors, he founded Hosea Williams Bail Bonds Inc, a bail bond agency located in Decatur, Ga.

Family and death

[edit]In early 1951, Williams married Juanita Terry. Together, Williams and Terry had eight children. Williams died at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, after a three-year battle with cancer on November 16, 2000. Funeral services were held at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where close friend Martin Luther King Jr., was once the co-pastor. Williams was preceded in death by his wife three months prior and by his son Hosea II two years earlier. Williams is interred at Lincoln Cemetery.

Legacy

[edit]Williams’ first comprehensive biography, Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest, was written by Dr. Rolundus R. Rice, an educator and historian who currently serves as COO and Vice President of Student Affairs at Tuskegee University. Rice traces Williams's journey from a local activist in Georgia to a national leader and one of Martin Luther King Jr.'s chief lieutenants.[10]

Boulevard Drive in the southeastern area of Atlanta was renamed Hosea L Williams Drive shortly before Williams died. Hosea Williams Drive runs by the site of his former home in the East Lake neighborhood at the intersection of Hosea L. Williams Drive and East Lake Drive. Hosea L. Williams Papers are housed at Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History in Atlanta. His daughter Elisabeth Omilami also maintains a traveling exhibit of valuable civil rights memorabilia. Williams was portrayed by Wendell Pierce in the 2014 film Selma.

Williams' granddaughter Porsha Williams stars on the Bravo reality TV series, The Real Housewives of Atlanta.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Unbought and Unbossed" was also the motto of former U.S. Representative Shirley Chisholm of New York City.

References

[edit]- ^ King Encyclopedia – Hosea Williams

- ^ Mettler, Suzanne (2004). Soldiers to Citizens: The G.I. Bill and the Making of the Greatest Generation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199887095. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Civil Rights Movement. Rowman & Littlefield. 2001. ISBN 9780810880375. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (1998). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 124. ISBN 0-684-80819-6.

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas. "Circa: Atlanta's Past In Pictures". Atlanta Magazine (April 2018): 128.

- ^ "International Civil Rights: Walk of Fame - Hosea Williams". www.nps.gov. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Civil Rights Act of 1964". Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2008.

- ^ Billy Hathorn, "The Frustration of Opportunity: Georgia Republicans and the Election of 1966", Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South, XXXI (Winter 1987–1988), p. 44.

- ^ Black Leaders of The Civil Rights Movement

- ^ "Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest". uscpress.com. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Williams v. Forsyth County Defense League, Federal-court complaint by Hosea Williams

- Daniel Lewis, "Hosea Williams, 74, Rights Crusader, Dies", The New York Times, November 17, 2000

- New Georgia Encyclopedia: Hosea Williams (1926–2000) Archived April 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Biographical information

- Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless Official Site

- Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History Archived October 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Giving back {Hosea Feed the Hungry}

- Hosea Williams Bail Bonds

- 1926 births

- 2000 deaths

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American United States Army personnel

- African-American state legislators in Georgia (U.S. state)

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- Atlanta City Council members

- County commissioners in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Democratic Party Georgia (U.S. state) state senators

- United States Army soldiers

- Morris Brown College alumni

- Clark Atlanta University alumni

- People from Decatur County, Georgia

- African-American activists

- Politicians from Atlanta

- Military personnel from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Selma to Montgomery marches

- Activists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Candidates in the 1972 United States elections

- African Americans in World War II

- 20th-century members of the Georgia General Assembly