Cambridge

Cambridge | |

|---|---|

Cambridge shown within Cambridgeshire | |

| Coordinates: 52°12′18″N 00°07′21″E / 52.20500°N 0.12250°E | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | East of England |

| County | Cambridgeshire |

| City region | Cambridgeshire and Peterborough |

| Founded | c. 1209 as Granta Brygg |

| City status | 1951 |

| Administrative HQ | Cambridge Guildhall |

| Government | |

| • Type | Non-metropolitan district |

| • Body | Cambridge City Council |

| • Executive | Leader and cabinet |

| • Control | Labour |

| • Leader | Mike Davey (L) |

| • Mayor | Baiju Thittala |

| • MPs | |

| Area | |

• Total | 16 sq mi (41 km2) |

| • Rank | 258th |

| Population (2022)[3] | |

• Total | 146,995 |

| • Rank | 151st |

| • Density | 9,360/sq mi (3,612/km2) |

| Demonym | Cantabrigian |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Dialling codes | 01223 |

| GSS code | E07000008 |

| Website | cambridge |

Cambridge (/ˈkeɪmbrɪdʒ/ ⓘ KAYM-brij)[5] is a city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, 55 miles (89 km) north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of the City of Cambridge was 145,700;[6] the population of the wider built-up area (which extends outside the city council area) was 181,137.[7] Cambridge became an important trading centre during the Roman and Viking ages, and there is archaeological evidence of settlement in the area as early as the Bronze Age. The first town charters were granted in the 12th century, although modern city status was not officially conferred until 1951.

The city is well known as the home of the University of Cambridge, which was founded in 1209 and consistently ranks among the best universities in the world.[8][9] The buildings of the university include King's College Chapel, Cavendish Laboratory, and the Cambridge University Library, one of the largest legal deposit libraries in the world. The city's skyline is dominated by several college buildings, along with the spire of the Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church, and the chimney of Addenbrooke's Hospital. Anglia Ruskin University, which evolved from the Cambridge School of Art and the Cambridgeshire College of Arts and Technology, also has its main campus in the city.

Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen or Cambridge Cluster, which contains industries such as software and bioscience and many start-up companies born out of the university. Over 40 per cent of the workforce have a higher education qualification, more than twice the national average. The Cambridge Biomedical Campus, one of the largest biomedical research clusters in the world, includes the headquarters of AstraZeneca and the relocated Royal Papworth Hospital.[10]

Cambridge produced the first 'Laws of the Game' for association football and was the site of the first game, which was held at Parker's Piece. The Strawberry Fair music and art festival and Midsummer Fair are held on Midsummer Common, and the annual Cambridge Beer Festival takes place on Jesus Green. The city is adjacent to the M11 and A14 roads.

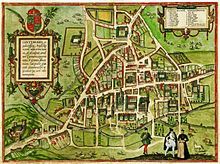

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Settlements have existed around the Cambridge area since prehistoric times. The earliest clear evidence of occupation is the remains of a 3,500-year-old farmstead discovered at the site of Fitzwilliam College.[11] Archaeological evidence of occupation through the Iron Age is a settlement on Castle Hill from the 1st century BC, perhaps relating to wider cultural changes occurring in southeastern Britain linked to the arrival of the Belgae.[12]

Roman

[edit]The principal Roman site is a small fort (castrum) Duroliponte on Castle Hill, just northwest of the city centre around the location of the earlier British village. The fort was bounded on two sides by the lines formed by the present Mount Pleasant, continuing across Huntingdon Road into Clare Street. The eastern side followed Magrath Avenue, with the southern side running near to Chesterton Lane and Kettle's Yard before turning northwest at Honey Hill.[13] It was constructed around AD 70 and converted to civilian use around 50 years later. Evidence of more widespread Roman settlement has been discovered, including numerous farmsteads[14] and a village in the Cambridge district of Newnham.[15]

Medieval

[edit]

Following the Roman withdrawal from Britain around 410, the location may have been abandoned by the Britons, although the site is usually identified as Cair Grauth,[16] as listed among the 28 cities of Britain in the History of the Britons attributed to Nennius.[18] Evidence exists that the invading Anglo-Saxons had begun occupying the area by the end of the century.[19] Their settlement – also on and around Castle Hill – became known as Grantebrycge[21] ("Granta-bridge". By Middle English, the settlement's name had changed to "Cambridg koe", deriving from the word 'Camboricum', meaning 'passage' or 'ford' of stream in a town or settlement,[22][23] and the lower stretches of the Granta changed their name to match.)[24]) Anglo-Saxon grave goods have been found in the area. During this period, Cambridge benefited from good trade links across the hard-to-travel fenlands. By the 7th century, the town was less significant and described by Bede as a "little ruined city" containing the burial site of Æthelthryth (Etheldreda).[20] Cambridge sat on the border between the East and Middle Anglian kingdoms, and the settlement slowly expanded on both sides of the river.[20]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Vikings arrived in 875; they imposed Viking rule, the Danelaw, by 878.[25] Their vigorous trading habits resulted in rapid growth of the town. During this period, the town's centre shifted from Castle Hill on the left bank of the river to the area now known as the Quayside on the right bank.[25] After the Viking period, the Saxons enjoyed a return to power, building churches, such as St Bene't's Church, as well as wharves, merchant houses, and a mint which produced coins with the town's name abbreviated to "Grant".[25]

In 1068, two years after the Norman Conquest of England, William the Conqueror erected a castle on Castle Hill, the motte of which survives.[20] Like the rest of the newly conquered kingdom, Cambridge fell under the control of the King and his deputies.

Cambridge's first town charter was granted by Henry I between 1120 and 1131. It granted the town monopoly of waterborne traffic and hithe tolls and recognised the borough court.[26] The distinctive Round Church dates from this period.[27] In 1209, Cambridge University was founded by Oxford students fleeing from hostility.[28][29] The oldest existing college, Peterhouse, was founded in 1284.[30]

Cambridge had a significant Jewish community in the middle ages, centred on what is now known as All Saints Passage, then known as the Jewry. A synagogue stood nearby. In January 1275, Eleanor of Provence expelled Jews from all of the towns within her dower lands, and the Jews of Cambridge were ordered to relocate to Norwich.[31]

In 1349, Cambridge was affected by the Black Death. Few records survive but 16 of 40 scholars at King's Hall died.[32] The town north of the river was severely impacted, being almost wiped out.[33] Following further depopulation after a second national epidemic in 1361, a letter from the Bishop of Ely suggested that two parishes in Cambridge be merged as there were not enough people to fill even one church.[32] With more than a third of English clergy dying in the Black Death, four new colleges were established at the university over the following years to train new clergymen, namely Gonville Hall, Trinity Hall, Corpus Christi, and Clare.[34]

In 1382, a revised town charter effected a "diminution of the liberties that the community had enjoyed", due to Cambridge's participation in the Peasants' Revolt. This charter transferred supervision of baking and brewing, weights and measures, and forestalling and regrating, from the town to the university.[26]

King's College Chapel was begun in 1446 by King Henry VI.[35] Built in phases by a succession of kings of England from 1446 to 1515 — its history intertwined with the Wars of the Roses — the chapel was completed during the reign of King Henry VIII.[35] The building would become synonymous with Cambridge, and currently is used in the logo for the Cambridge City Council.[36]

Early modern

[edit]

Following repeated outbreaks of pestilence throughout the 16th century,[37] sanitation and fresh water were brought to Cambridge by the construction of Hobson's Conduit in the early 1600s. Water was brought from Nine Wells, at the foot of the Gog Magog Hills to the southeast of Cambridge, into the centre of the town.[38]

Cambridge played a significant role in the early part of the English Civil War as it was the headquarters of the Eastern Counties Association, an organisation administering a regional East Anglian army, which became the mainstay of the Parliamentarian military effort before the formation of the New Model Army.[39] In 1643 control of the town was given by Parliament to Oliver Cromwell, who had been educated at Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge.[40] The town's castle was fortified and garrisoned with troops and some bridges were destroyed to aid its defence. Although Royalist forces came within 2 miles (3 km) of the town in 1644, the defences were never used, and the garrison was stood down the following year.[39]

Early-industrial era

[edit]In the 19th century, in common with many other English towns, Cambridge expanded rapidly, due in part to increased life expectancy and improved agricultural production leading to increased trade in town markets.[41] The Inclosure Acts of 1801 and 1807 enabled the town to expand over surrounding open fields.[42]

The railway came to Cambridge in 1845 after initial resistance, with the opening of the Great Eastern Railway's London to Norwich line. The station was outside the town centre following pressure from the university to restrict travel by undergraduates.[43] With the arrival of the railway and associated employment came development of areas around the station, such as Romsey Town.[44] The rail link to London stimulated heavier industries, such as the production of brick, cement and malt.[41]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]From the 1930s to the 1980s, the size of the city was increased by several large council estates.[45] The biggest impact has been on the area north of the river, which are now the estates of East Chesterton, King's Hedges, and Arbury where Archbishop Rowan Williams lived and worked as an assistant priest in the early 1980s.[46]

During World War II, Cambridge was an important centre for defence of the east coast. The town became a military centre, with an R.A.F. training centre and the regional headquarters for Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, Hertfordshire, and Bedfordshire established during the conflict.[39] The town itself escaped relatively lightly from German bombing raids, which were mainly targeted at the railway. 29 people were killed and no historic buildings were damaged. In 1944, a secret meeting of military leaders held in Trinity College laid the foundation for the allied invasion of Europe.[41] During the war Cambridge served as an evacuation centre for over 7,000 people from London, as well as for parts of the University of London.[39]

Cambridge was granted its city charter in 1951 in recognition of its history, administrative importance and economic success.[39] Cambridge does not have a cathedral, traditionally a prerequisite for city status, instead falling within the Church of England Diocese of Ely. In 1962, Cambridge's first shopping arcade, Bradwell's Court, opened on Drummer Street, though this was demolished in 2006.[47] Other shopping arcades followed at Lion Yard, which housed a relocated Central Library for the city, and the Grafton Centre which replaced Victorian housing stock which had fallen into disrepair in the Kite area of the city. This latter project was controversial at the time.[48]

The city gained its second university in 1992 when Anglia Polytechnic became Anglia Polytechnic University. Renamed Anglia Ruskin University in 2005, the institution has its origins in the Cambridge School of Art opened in 1858 by John Ruskin.

Governance

[edit]

There are two main tiers of local government covering Cambridge, at district and county level: Cambridge City Council and Cambridgeshire County Council. Since 2017, both authorities have been members of the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority. The leader of the city council is the city's representative on the combined authority, which is led by the directly-elected Mayor of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough.[49][50] The district covers most of the city's urban area, although some suburbs extend into the surrounding South Cambridgeshire district. The city council's headquarters are in the Guildhall, a large building in the market square.[51][52]

Westminster

[edit]The parliamentary constituency of Cambridge covers most of the city; Daniel Zeichner (Labour) has represented the seat since the 2015 general election. The seat was generally held by the Conservatives until it was won by Labour in 1992, then taken by the Liberal Democrats in 2005 and 2010, before returning to Labour in 2015. A southern area of the city, Queen Edith's ward and Cherry Hinton ward,[53] falls within the South Cambridgeshire constituency, whose MP is Pippa Heylings (Lib Dems), first elected in 2024.

The University of Cambridge formerly had two seats in the House of Commons; Sir Isaac Newton was one of the most notable MPs. The Cambridge University constituency was abolished under 1948 legislation, and ceased at the dissolution of Parliament for the 1950 general election, along with the other university constituencies.

Administrative history

[edit]Cambridge was an ancient borough. Its earliest known municipal charter was issued by Henry I in the early 12th century.[54] A subsequent charter from King John in 1207 permitted the appointment of a mayor;[55] the first recorded mayor, Harvey FitzEustace, served in 1213.[56] Until the 20th century, the borough covered the same area as Cambridge's fourteen ancient parishes.[a] The borough did not include Cambridge Castle, which was in the neighbouring parish of Chesterton.[57][42]

The borough was reformed to become a municipal borough in 1836 under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.[58] The borough's responsibilities were primarily judicial and regulatory rather than providing public services or infrastructure. A separate body of improvement commissioners was established in 1788 to maintain the city's streets, and the commissioners were gradually given other local government functions relating to sewers and public health. The commissioners were abolished in 1889 and their functions taken on by the borough council.[59][60]

The borough was enlarged in 1912 to take in Chesterton to the north and some areas from neighbouring parishes to the south.[61] It was extended again in 1934 to take in Cherry Hinton, Trumpington, and parts of several other neighbouring parishes.[62] The borough was awarded city status in 1951.[63] In 1974, Cambridge was made a non-metropolitan district; it kept the same boundaries, which had last been expanded in 1934, but there were changes to the council's responsibilities.[64]

Geography and environment

[edit]

Cambridge is situated about 55 miles (89 km) north-by-east of London and 95 miles (153 kilometres) east of Birmingham. The city is located in an area of level and relatively low-lying terrain just south of the Fens, which varies between 6 and 24 metres (20 and 79 ft) above sea level.[65] The town was thus historically surrounded by low-lying wetlands that have been drained as the town has expanded.[66]

The underlying geology of Cambridge consists of gault clay and Chalk Marl, known locally as Cambridge Greensand,[67] partly overlaid by terrace gravel.[66] A layer of phosphatic nodules (coprolites) under the marl was mined in the 19th century for fertiliser; this became a major industry in the county, and its profits yielded buildings such as the Corn Exchange, Fulbourn Hospital, and St. John's Chapel until the Quarries Act 1894 and competition from America ended production.[67]

The River Cam flows through the city from the village of Grantchester, to the southwest. It is bordered by water meadows within the city such as Sheep's Green as well as residential development.[66] Like most cities, modern-day Cambridge has many suburbs and areas of high-density housing. The city centre of Cambridge is mostly commercial, historic buildings, and large green areas such as Jesus Green, Parker's Piece and Midsummer Common. Some of the roads in the centre are pedestrianised.

Population growth has seen new housing developments in the 21st century, with estates such as the CB1[68] and Accordia schemes near the station,[69] and developments such as Great Kneighton, formally known as Clay Farm,[70] and Trumpington Meadows[71] currently under construction in the south of the city. Other major developments currently being constructed in the city are Darwin Green (formerly NIAB), and University-led developments at West Cambridge and North West Cambridge, (Eddington).

The entire city centre, as well as parts of Chesterton, Petersfield, West Cambridge, Newnham, and Abbey, are covered by an Air Quality Management Area, implemented to counter high levels of nitrogen dioxide in the atmosphere.[72]

Climate

[edit]The city has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb).[73] Cambridge has an official weather observing station, at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, about one mile (1.6 km) south of the city centre. In addition, the Digital Technology Group of the university's Department of Computer Science and Technology[74] maintains a weather station on the West Cambridge site, displaying current weather conditions online via web browsers or an app, and also an archive dating back to 1995.[75]

The city, like most of the UK, has a maritime climate highly influenced by the Gulf Stream. Located in the driest region of Britain,[76][77] Cambridge's rainfall averages around 570 mm (22.44 in) per year, around half the national average.[78] The driest recent year was in 2011 with 380.4 mm (14.98 in)[79] of rain at the Botanic Garden and 347.2 mm (13.67 in) at the NIAB site.[80] This is just below the semi-arid precipitation threshold for the area, which is 350 mm of annual precipitation.[81] Conversely, 2012 was the wettest year on record, with 812.7 mm (32.00 in) reported.[82] Snowfall accumulations are usually small, in part because of Cambridge's low elevation, and low precipitation tendency during transitional snow events.

Owing to its low-lying, inland, and easterly position within the British Isles, summer temperatures tend to be somewhat higher than areas further west, and often rival or even exceed those recorded in the London area. Cambridge also often records the annual highest national temperature in any given year – 30.2 °C (86.4 °F) in July 2008 at NIAB[83] and 30.1 °C (86.2 °F) in August 2007 at the Botanic Garden[84] are two recent examples. Other years include 1876, 1887, 1888, 1892, 1897, 1899 and 1900.[85] The absolute maximum stands at 39.9 °C (103.8 °F) recorded on 19 July 2022 at Cambridge University Botanic Garden.[86] Before this date, Cambridge held the record for the all-time maximum temperature in the UK, after recording 38.7 °C (101.7 °F) on 25 July 2019. Typically the temperature will reach 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or higher on over 25 days of the year over the 1981–2010 period,[87] with the annual warmest day averaging 31.5 °C (88.7 °F)[88] over the same period.

The absolute minimum temperature recorded at the Botanic Garden site was −17.2 °C (1.0 °F), recorded in February 1947,[89] although a minimum of −17.8 °C (0.0 °F) was recorded at the now defunct observatory site in December 1879.[90] More recently the temperature fell to −15.3 °C (4.5 °F) on 11 February 2012,[91] −12.2 °C (10.0 °F) on 22 January 2013[92] and −10.9 °C (12.4 °F)[93] on 20 December 2010. The average frequency of air frosts ranges from 42.8 days at the NIAB site,[94] to 48.3 days at the Botanic Garden[95] per year over the 1981–2010 period. Typically the coldest night of the year at the Botanic Garden will fall to −8.0 °C (17.6 °F).[96] Such minimum temperatures and frost averages are typical for inland areas across much of southern and central England.

Sunshine averages around 1,500 hours a year or around 35% of possible, a level typical of most locations in inland central England.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.7 (60.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

39.9 (103.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.1 (3.0) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.2 (1.86) |

35.9 (1.41) |

32.2 (1.27) |

36.2 (1.43) |

43.9 (1.73) |

52.3 (2.06) |

53.2 (2.09) |

57.6 (2.27) |

49.3 (1.94) |

56.5 (2.22) |

54.4 (2.14) |

49.8 (1.96) |

568.4 (22.38) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.7 | 8.9 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 107.3 |

| Source: ECA&D[97] | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

39.9 (103.8) |

36.1 (97.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.0 (3.2) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 48.6 (1.91) |

35.7 (1.41) |

32.9 (1.30) |

37.6 (1.48) |

43.2 (1.70) |

49.1 (1.93) |

48.3 (1.90) |

55.9 (2.20) |

47.6 (1.87) |

58.7 (2.31) |

52.6 (2.07) |

49.2 (1.94) |

559.4 (22.02) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.4 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 107.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57.2 | 77.8 | 118.4 | 157.2 | 182.7 | 182.5 | 190.0 | 181.3 | 144.0 | 110.3 | 67.6 | 53.7 | 1,522.7 |

| Source 1: Met Office[98] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Starlings Roost Weather[99][100] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]The city contains three Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), at Cherry Hinton East Pit, Cherry Hinton West Pit, and Travellers Pit,[101] and ten Local Nature Reserves (LNRs): Sheep's Green and Coe Fen, Coldham's Common, Stourbridge Common, Nine Wells, Byron's Pool, West Pit, Paradise, Barnwell West, Barnwell East, and Logan's Meadow.[102]

Green belt

[edit]Cambridge is completely enclosed by green belt as a part of a wider environmental and planning policy first defined in 1965 and formalised in 1992.[103][104] While some small tracts of green belt exist on the fringes of the city's boundary, much of the protection is in the surrounding South Cambridgeshire[105] and nearby East Cambridgeshire[106] districts, helping to maintain local green space, prevent further urban sprawl and unplanned expansion of the city, as well as protecting smaller outlying villages from further convergence with each other as well as the city.[107]

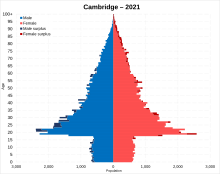

Demography

[edit]

At the 2011 census, the population of the Cambridge contiguous built-up area (urban area) was 158,434,[108] while that of the City Council area was 123,867.[109]

In the 2001 Census held during University term, 89.44% of Cambridge residents identified themselves as white, compared with a national average of 92.12%.[110] Within the university, 84% of undergraduates and 80% of post-graduates identified as white (including overseas students).[111]

Cambridge has a much higher than average proportion of people in the highest paid professional, managerial or administrative jobs (32.6% vs. 23.5%)[112] and a much lower than average proportion of manual workers (27.6% vs. 40.2%).[112] In addition, 41.2% have a higher-level qualification (e.g. degree, Higher National Diploma, Master's or PhD), much higher than the national average proportion (19.7%).[113]

Centre for Cities identified Cambridge as the UK's most unequal city in 2017 and 2018. Residents' income was the least evenly distributed of 57 British cities measured, with its top 6% earners accounting for 19% of its total income and the bottom 20% for only 2%, and a Gini coefficient of 0.460 in 2018.[114][115]

Historical population

[edit]| Year | Population | Year | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1749 | 6,131 | 1901 | 38,379 | |||

| ⋮ | 1911 | 40,027 | ||||

| 1801 | 10,087 | 1921 | 59,212 | |||

| 1811 | 11,108 | 1931 | 66,789 | |||

| 1821 | 14,142 | 1951 | 81,500 | |||

| 1831 | 20,917 | 1961 | 95,527 | |||

| 1841 | 24,453 | 1971 | 99,168 | |||

| 1851 | 27,815 | 1981 | 87,209 | |||

| 1861 | 26,361 | 1991 | 107,496 | |||

| 1871 | 30,078 | 2001 | 108,863 | |||

| 1891 | 36,983 | 2011 | 123,900 | |||

Local census 1749[116] Census: Regional District 1801–1901[117] Civil Parish 1911–1961[118] District 1971–2011[119]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic Group | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[120] | 2001[121] | 2011[122] | 2021[123] | |||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 86,519 | 94.1% | 97,365 | 89.4% | 102,205 | 82.5% | 108,570 | 74.6% |

| White: British | – | – | 85,472 | 78.5% | 81,742 | 66.0% | 77,195 | 53.0% |

| White: Irish | – | – | 1,708 | 1.6% | 1,767 | 1.4% | 1,885 | 1.3% |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | 109 | 0.1% | 110 | 0.1% | ||

| White: Roma | 885 | 0.6% | ||||||

| White: Other | – | – | 10,185 | 9.4% | 18,587 | 15.0% | 28,495 | 19.6% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 3,371 | 3.7% | 6,410, | 5.9% | 13,618, | 11% | 21,626 | 14.9% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 906 | 1.0% | 1,952 | 1.8% | 3,413 | 2.8% | 5916 | 4.1% |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 248 | 0.3% | 513 | 0.5% | 742 | 0.7% | 1500 | 1.0% |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 438 | 0.4% | 976 | 0.9% | 1,849 | 1.7% | 2874 | 2.0% |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 909 | 1.0% | 2,325 | 2.1% | 4,454 | 3.6% | 6362 | 4.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 870 | 0.9% | 644 | 0.6% | 3,160 | 2.6% | 4974 | 3.4% |

| Black or Black British: Total | 1,080 | 1.2% | 1,461 | 1.3% | 2,097 | 1.7% | 3,561 | 2.4% |

| Black or Black British: African | 315 | 786 | 1,300 | 2519 | 1.7% | |||

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 454 | 547 | 598 | 639 | 0.4% | |||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | 311 | 128 | 199 | 403 | 0.3% | |||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | 2,141 | 2% | 3,944 | 3.2% | 7,410 | 5.2% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | 454 | 728 | 1152 | 0.8% | ||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | 214 | 470 | 1010 | 0.7% | ||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | 735 | 1,501 | 2987 | 2.1% | ||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | 738 | 1,245 | 2261 | 1.6% | ||

| Other: Total | 963 | 1% | 1,486 | 1.4% | 2,003 | 1.6% | 4,507 | 3.1% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | 908 | 1,141 | 0.8% | |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 963 | 1% | 1,486 | 1.4% | 1,095 | 3,366 | 2.3% | |

| Total | 91,933 | 100% | 108,863 | 100% | 123,867 | 100% | 145,674 | 100% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 2001[124] | 2011[125] | 2021[126] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Holds religious beliefs | 69,433 | 63.8 | 65,828 | 53.1 | 66,225 | 45.5 |

| 62,764 | 57.7 | 55,514 | 44.8 | 51,335 | 35.2 | |

| 1,139 | 1.0 | 1,573 | 1.3 | 1,668 | 1.1 | |

| 1,293 | 1.2 | 2,058 | 1.7 | 3,301 | 2.3 | |

| 850 | 0.8 | 870 | 0.7 | 1,057 | 0.7 | |

| 2,651 | 2.4 | 4,897 | 4.0 | 7,392 | 5.1 | |

| 205 | 0.2 | 213 | 0.2 | 322 | 0.2 | |

| Other religion | 531 | 0.5 | 703 | 0.6 | 1,122 | 0.8 |

| No religion | 28,965 | 26.6 | 46,839 | 37.8 | 65,160 | 44.7 |

| Religion not stated | 10,465 | 9.6 | 11,200 | 9.0 | 14,315 | 9.8 |

| Total population | 108,863 | 100.0 | 123,867 | 100.0 | 145,700 | 100.0 |

Economy

[edit]

The town's river link to the surrounding agricultural land, and good road connections to London in the south meant Cambridge has historically served as an important regional trading post. King Henry I granted Cambridge a monopoly on river trade, privileging this area of the economy of Cambridge.[127] The town market provided for trade in a wide variety of goods and annual trading fairs such as Stourbridge Fair and Midsummer Fair were visited by merchants from across the country. The river was described in an account of 1748 as being "often so full of [merchant boats] that the navigation thereof is stopped for some time".[128] For example, 2000 firkins of butter were brought up the river every Monday from the agricultural lands to the northeast, particularly Norfolk, to be unloaded in the town for road transportation to London.[128] Changing patterns of retail distribution and the advent of the railways led to a decline in Cambridge's importance as a market town.[129]

Cambridge today has a diverse economy with strength in sectors such as research and development, software consultancy, high value engineering, creative industries, pharmaceuticals and tourism.[130] Described as one of the "most beautiful cities in the world" by Forbes in 2010,[131] with the view from The Backs being selected as one of the 10 greatest in England by National Trust chair Simon Jenkins. Tourism generates over £750 million for the city's economy.[132]

Cambridge and its surrounds are sometimes referred to as Silicon Fen, an allusion to Silicon Valley, because of the density of high-tech businesses and technology incubators that have developed on science parks around the city. Many of these parks and buildings are owned or leased by university colleges, and the companies often have been spun out of the university.[133] Cambridge Science Park, which is the largest commercial R&D centre in Europe, is owned by Trinity College;[134][135] St John's is the landlord of St John's Innovation Centre.[136] Technology companies include Abcam, CSR, ARM Limited, CamSemi, Jagex and Sinclair.[137] Microsoft has located its Microsoft Research UK offices in West Cambridge, separate from the main Microsoft UK campus in Reading, and also has an office on Station Road.

Cambridge was also the home of Pye Ltd, founded in 1898 by W. G. Pye, who worked in the Cavendish Laboratory; it began by supplying the university and later specialised in wireless telegraphy equipment, radios, televisions and also defence equipment.[41] Pye Ltd evolved into several other companies including TETRA radio equipment manufacturer Sepura. Another major business is Marshall Aerospace located on the eastern edge of the city. The Cambridge Network keeps businesses in touch with each other.

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]Cambridge City Airport has no scheduled services and is used mainly by charter and training flights[138] and by Marshall Aerospace for aircraft maintenance. London Stansted Airport, about 30 miles (48 km) south via the M11 or direct rail, offers a broad range of international destinations.

Cycling

[edit]

The city lies on fairly flat land and has the highest level of cycle use in the UK.[139] According to the 2001 census, 25% of residents travelled to work by bicycle. Furthermore, a survey in 2013 found that 47% of residents travel by bike at least once a week.[140]

Railway

[edit]

Cambridge railway station was opened in 1845.[141] Trains run to King's Lynn and Ely (via the Fen Line), Norwich (via the Breckland Line), Leicester, Birmingham New Street, Peterborough, Stevenage, Ipswich, Stansted Airport, Brighton and Gatwick Airport.

The station has direct rail links to London with termini at London King's Cross (via the Cambridge Line and the East Coast Main Line), Liverpool Street (on the West Anglia Main Line) and St Pancras (on the Thameslink line). Fast trains to London King's Cross run every half-hour during peak hours, with a journey time of 53 minutes, and these are supplemented by semi-fast trains to Brighton via London St Pancras, and slow trains to London King's Cross.[142] The station's original line to London was to Bishopsgate, via Bishops Stortford.

A second railway station, Cambridge North, opened on 21 May 2017; it was originally planned to open in March 2015.[143][144][145] A third railway station, Cambridge South, near Addenbrooke's Hospital is now under construction;[146] it is expected to open in 2025.[147] The former station of Cherryhinton, for Cherry Hinton, operated when it was separate village to Cambridge.

Several railway lines were closed during the 1960s, including the Cambridge and St Ives branch line, the Stour Valley Railway, the Cambridge to Mildenhall railway and the Varsity Line to Oxford.

Road

[edit]Areas outside the centre are car dependent causing traffic congestion in the drivable parts of centre.[148] The M11 motorway from east London terminates to the north-west of the city where it joins the A14, a road from the port of Felixstowe to Rugby. The A428 connects the city with the A1 at St Neots as the A421 (via Bedford and Milton Keynes) on to Oxford. The A10 connects via Ely to King's Lynn to the north and the historic route south to the City of London.

Buses

[edit]

Cambridge has five Park and Ride sites, all of which operate seven days a week and are aimed at encouraging motorists to park near the city's edge.[149] Since 2011, the Cambridgeshire Guided Busway has carried bus services into the centre of Cambridge from St Ives, Huntingdon and other towns and villages along the routes, operated by Stagecoach in the Fens and Whippet.[150] The A service continues on to the railway station and Addenbrookes, before terminating at a new Park and Ride in Trumpington. Since 2017, it has also linked to Cambridge North railway station.

Service 905 provides a connection with Oxford, although passengers wishing to continue beyond Bedford have to change to service X5; both services are operated by Stagecoach East and run daily.

Future plans

[edit]In February 2020, consultations opened for a transport system known as the Cambridgeshire Autonomous Metro. It would have connected the historic city centre and the existing busway route with the mainline railway stations, Cambridge Science Park and Haverhill.[151] In May 2021 the newly elected mayor said he was focused instead on a "revamped bus network" but would not yet abandon the work done. As of November 2022[update], the Greater Cambridge Partnership is consulting on plans comprising: transforming the bus network; investing in other sustainable travel schemes; and introducing a Cambridge Congestion Charge as part of a Sustainable Travel Zone.[152]

In 2024, Cambridge Connect proposed repurposing the planned route of the canceled metro as a light railway. Known as the Isaac Newton line, it would connect the mainline railway stations with Cambourne, the guided busway station at Trumpington, Haverhill, Addenbrookes Hospital, and a new station in Cambridge city centre.[153]

Education

[edit]

Cambridge's two universities,[154] the collegiate University of Cambridge and the local campus of Anglia Ruskin University, serve around 30,000 students, by some estimates.[155] Cambridge University stated its 2020/21 student population was 24,270,[156] and Anglia Ruskin reports 24,000 students across its two campuses (one of which is outside Cambridge, in Chelmsford) for the same period.[157] ARU now (2019) has additional campuses in London and Peterborough. State provision in the further education sector includes Hills Road Sixth Form College, Long Road Sixth Form College, and Cambridge Regional College. The Open University had a presence in the city between 1979 and 2018.[158][159][160]

Both state and private schools serve Cambridge pupils from nursery to secondary school age. State schools are administered by Cambridgeshire County Council, which maintains 251 schools in total,[161] 35 of them in Cambridge city.[162] Netherhall School, Chesterton Community College, the Parkside Federation (comprising Parkside Community College and Coleridge Community College), North Cambridge Academy and the Christian inter-denominational St Bede's School provide comprehensive secondary education.[163] Many other pupils from the Cambridge area attend village colleges, an educational institution unique to Cambridgeshire, which serve as secondary schools during the day and adult education centres outside of school hours.[164] Independent schools in the city include The Perse School, Stephen Perse Foundation, Sancton Wood School, St Mary's School, Heritage School and The Leys School.[165] The city has one university technical college, Cambridge Academy for Science and Technology, which opened in September 2014.

Sport

[edit]Football

[edit]

Cambridge played a unique role in the invention of modern football: the game's first set of rules were drawn up by members of the university in 1848. The Cambridge Rules were first played on Parker's Piece and had a "defining influence on the 1863 Football Association rules", which again were first played on Parker's Piece.[166]

The city is home to Cambridge United, who play at the Abbey Stadium. Formed in 1912 as Abbey United, they were elected to the Football League in 1970 and reached the Second Division in 1978, although a serious decline in them in the mid-1980s saw them drop back down to the Fourth Division and almost go out of business. Success returned to the club in the early 1990s when they won two successive promotions and reached the FA Cup quarter finals in both of those seasons and, in 1992, they came close to becoming the first English team to win three successive Football League promotions which would have taken them into the newly created FA Premier League; however, they were beaten in the play-offs and another decline set in. In 2005, they were relegated from the Football League and, for the second time in twenty years, narrowly avoided going out of business. After nine years of non-league football, they returned to the Football League in 2014 by winning the Conference National play-offs.

Cambridge United WFC is a women's only football club based in Cambridge. The team compete in the FA Women's National League South East. The club plays home games at St Neots Town's Rowley Park stadium and the Abbey Stadium.

Cambridge City, of the Northern Premier League Division One Midlands, now play in neighbouring St Ives. Formed in 1908 as Cambridge Town, the club were Southern Premier League champions in 1962–63, the highest they have finished in the English football pyramid. After a legal dispute with their landlords,[167] the club left their City Ground stadium in 2013 to groundshare at Histon's Bridge Road ground. The club have plans to open their own new ground in Sawston in 2024.[168]

Cricket

[edit]Parker's Piece was used for first-class cricket matches from 1817 to 1864.[169] The University of Cambridge's cricket ground, Fenner's, is located in the city and is one of the home grounds for minor counties team Cambridgeshire CCC.[170] The Cambridgeshire Cricket Association operates an amateur club cricket league with six adult divisions, including numerous clubs in the city, plus junior divisions.[171] Most of the university colleges also operate their own teams, and there are several casual village cricket teams that play in the city suburbs.

Rugby

[edit]The city is represented in both codes of Rugby football. Rugby union club Cambridge R.U.F.C. were founded in 1923 [172] and play in the RFU Championship[173] at their home ground, Grantchester Road, in the south-west corner of the city. Cambridge Lions represent the city in rugby league and are members of East Rugby League.[174]

Watersports

[edit]

The River Cam, which runs through the city centre, is used for boating. The university and its colleges are well known for rowing and the Cambridgeshire Rowing Association, formed in 1868, organises competitive rowing on the river outside of the university.[175] Rowing clubs based in the city include City of Cambridge RC, Cambridge '99 RC, Cantabrigian RC and Rob Roy BC. Parts of the Cam are used for recreational punting, a type of boating in which the craft is propelled by pushing against the river bed with a quant pole.

Cambridge Swimming Club, Cambridge Dive team and City of Cambridge Water Polo Club are all based at Parkside Swimming Pool.[176]

Parkour/freerunning

[edit]Home and training ground to many influential traceurs, Cambridge is well known for its vibrant, and at times high-profile, parkour and freerunning scene.[177][178]

Other sports

[edit]Cambridge is home to two real tennis courts (out of about 50 in the world) at Cambridge University Real Tennis Club.[179][180] Cambridgeshire Cats play American football at Coldham's Common. Cambridge Royals are members of the British Baseball Federation's Triple-A South Division.[181] Cambridge has two cycling clubs: Team Cambridge[182] and Cambridge Cycling Club.[183] Cambridge & Coleridge Athletic Club[184] is the city's track and field club, based at the University of Cambridge's Wilberforce Road track. Cambridge Triathlon Club is based at Impington Village College.[185] Cambridge Handball Club compete in the men's England Handball National Super 8 League and the women's England Handball National Super 7 League. There are three field hockey clubs; Cambridge City Hockey Club, Cambridge South Hockey Club and Cambridge Nomads. The city is also represented in polo by Cambridge Polo Club, based in Barton, just outside the city. The Romsey Town Rollerbillies play roller derby in Cambridge.[186] Cambridge Parnells GAA represent the area in Gaelic football, playing out of Coldham's Common and participating in the Hertfordshire GAA Championship.[187] Speedway racing was formerly staged at a greyhound stadium in Coldhams Lane.[188]

Varsity sports

[edit]Cambridge is known for the sporting events between the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford, especially the rugby union Varsity Match and the Boat Race, though many of these do not take place within either Cambridge or Oxford.

Culture

[edit]

Theatre

[edit]Cambridge's main traditional theatre is the Arts Theatre, a venue with 666 seats in the town centre.[189] The theatre often has touring shows, as well as those by local companies. The largest venue in the city to regular hold theatrical performances is the Cambridge Corn Exchange with a capacity of 1,800 standing or 1,200 seated. Housed within the city's 19th century former corn exchange building the venue was used for a variety of additional functions throughout the 20th century including tea parties, motor shows, sports matches and a music venue with temporary stage.[190] The City Council renovated the building in the 1980s, turning it into a full-time arts venue, hosting theatre, dance and music performances.[190] The newest theatre venue in Cambridge is the 220-seat J2, part of Cambridge Junction in Cambridge Leisure Park. The venue was opened in 2005 and hosts theatre, dance, live music and comedy[191] The ADC Theatre is managed by the University of Cambridge, and typically has 3 shows a week during term time. It hosts the Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club which has produced many notable figures in British comedy. The Mumford Theatre is part of Anglia Ruskin University, and hosts shows by both student and non-student groups. There are also a number of venues within the colleges.

Museums

[edit]Within the city there are several notable museums, some run by the University of Cambridge Museums consortium and others independent of it.

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the city's largest, and is the lead museum of the University of Cambridge Museums. Founded in 1816 from the bequeathment and collections of Richard, Viscount FitzWilliam, the museum was originally located in the building of the Perse Grammar School in Free School Lane.[192] After a brief housing in the University of Cambridge library, it moved to its current, purpose-built building on Trumpington Street in 1848.[192] The museum has five departments: Antiquities; Applied Arts; Coins and Medals; Manuscripts and Printed Books; and Paintings, Drawings and Prints. Other members of the University of Cambridge Museums are the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, The Polar Museum, The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Museum of Classical Archaeology, The Whipple Museum of the History of Science, and the University Museum of Zoology.

The Museum of Cambridge, formerly known as the Cambridge & County Folk Museum, is a social history museum located in a former pub on Castle Street.[193] The Centre for Computing History, a museum dedicated to the story of the Information Age, moved to Cambridge from Haverhill in 2013.[194] Housed in a former sewage pumping station, the Cambridge Museum of Technology has a collection of large exhibits related to the city's industrial heritage.

Music

[edit]Popular music

[edit]Pink Floyd are the most notable band with roots in Cambridge. The band's former songwriter, guitarist and vocalist Syd Barrett was born and lived in the city, and he and another founding member, Roger Waters, went to school together at Cambridgeshire High School for Boys. David Gilmour, the guitarist who replaced Barrett, was also a Cambridge resident and attended the nearby Perse School. Bands that were formed in Cambridge include Clean Bandit, Henry Cow, the Movies, Katrina and the Waves, the Soft Boys,[195] Ezio[196] the Broken Family Band,[197] Uncle Acid & the Deadbeats,[198] and the pop-classical group the King's Singers, who were formed at the university.[199] Solo artist Boo Hewerdine[200] is from Cambridge, as are drum and bass artists (and brothers) Nu:Tone and Logistics. Singers Matthew Bellamy,[201] of the rock band Muse, Tom Robinson,[202] Olivia Newton-John[203] and Charli XCX were born in the city. 2012 Mercury Prize winners Alt-J are based in Cambridge.[204]

Live music venues hosting popular music in the city include the Cambridge Corn Exchange, Cambridge Junction, the Portland Arms, and The Blue Moon.[205][206]

Classical music

[edit]Started in 1991, the annual Cambridge Music Festival takes place each November.[207] The Cambridge Summer Music Festival takes place in July.[208]

Contemporary art

[edit]Cambridge contains Kettle's Yard gallery of modern and contemporary art and the Heong Gallery which opened to the public in 2016 at Downing College.[209] Anglia Ruskin University operates the publicly accessible Ruskin Gallery within the Cambridge School of Art.[210] Wysing Arts Centre, one of the leading research centres for the visual arts in Europe, is associated with the city, though is located several miles west of Cambridge.[211] Artist-run organisations including Aid & Abet,[205] Cambridge Art Salon, Changing Spaces[212] and Motion Sickness[213] also run exhibitions, events and artists' studios in the city, often in short-term or temporary spaces.

Festivals and events

[edit]

Several fairs and festivals take place in Cambridge, mostly during the British summer. Midsummer Fair dates back to 1211, when it was granted a charter by King John.[214] Today it exists primarily as an annual funfair with the vestige of a market attached and is held over several days around or close to midsummers day. On the first Saturday in June Midsummer Common is the site for Strawberry Fair, a free music and children's fair, with various market stalls. For one week in May, on Jesus Green, the annual Cambridge Beer Festival has been held since 1974.[215]

Launched in 1977 Cambridge Film Festival is the third-longest-running film festival in the UK. Presented annually each autumn by the Cambridge Film Trust, the Festival showcases a selection of around 100, predominantly independent and specialised, films and embeds them within a programme of special events, Q&As, and talks.

Cambridge Folk Festival is held annually in the grounds of Cherry Hinton Hall. The festival has been organised by the city council since its inception in 1964. The Cambridge Summer Music Festival is an annual festival of classical music, held in the university's colleges and chapels.[216] The Cambridge Shakespeare Festival is an eight-week season of open-air performances of the works of William Shakespeare, held in the gardens of various colleges of the university.[217]

The Cambridge Science Festival, typically held annually in March, is the United Kingdom's largest free science festival.[218] The Cambridge Literary Festival, which focusses on contemporary literary fiction and non-fiction, is held bi-annually in April and November.[219] Between 1975 and 1985 the Cambridge Poetry Festival was held biannually.[220] Other festivals include the annual Mill Road Winter Fair, held the first Saturday of December,[221] the E-luminate Festival, which took place every February from 2013 to 2018,[222][223] and The Big Weekend, a city outdoor event organised by the City Council every July.[224]

Three Cambridge Free Festivals held in 1969, 1970, and 1971 that featured artists including David Bowie, King Crimson, Roy Harper, Spontaneous Combustion, UFO and others are believed by the festival organiser to have been the first free multiple-day rock music festivals held in the UK.[225][226][227][228][229][230][231][232][233]

Literature and film

[edit]The city has been the setting for all or part of several novels, including Douglas Adams' Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency, Rose Macaulay's They Were Defeated,[234] Kate Atkinson's Case Histories,[235] Rebecca Stott's Ghostwalk[236] and Robert Harris' Enigma,[237][238] while Susanna Gregory wrote a series of novels set in 14th century Cambridge.[239] Gwen Raverat, the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, talked about her late Victorian Cambridge childhood in her memoir Period Piece, and The Night Climbers of Cambridge is a book written by Noel Symington under the pseudonym "Whipplesnaith" about nocturnal climbing on the colleges and town buildings of Cambridge in the 1930s.[240]

Fictionalised versions of Cambridge appear in Philippa Pearce's Tom's Midnight Garden and Minnow on the Say, the city renamed as Castleford, and as the home of Tom Sharpe's fictional college in Porterhouse Blue.[241]

ITV TV series Granchester was partly filmed in Cambridge.[242]

Television

[edit]News and television programmes are broadcast from the BBC Look East (West) studio in Cambridge.[243]

Radio

[edit]Local radio stations are BBC Radio Cambridgeshire on 96.0 FM, Heart East on 103.0 FM, Cambridge 105 on 105 FM, Star Radio on 100.7 FM and Cam FM on 97.2 is a student run-radio station at the University of Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin University.

Newspapers

[edit]The city's local newspapers are Cambridge News, Cambridge Independent and Varsity, the student newspaper of the University of Cambridge.

Public services

[edit]

Cambridge is served by Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, with several smaller medical centres in the city and a teaching hospital at Addenbrooke's. Located on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Addenbrooke's is one of the largest hospitals in the United Kingdom and is a designated regional trauma centre. The East of England Ambulance Service covers the city and has an ambulance station on Hills Road.[244] The smaller Brookfields Hospital stands on Mill Road.[245] Cambridgeshire Constabulary provides the city's policing; the main police station is at Parkside,[246] adjacent to the city's fire station, operated by Cambridgeshire Fire and Rescue Service.[247]

Cambridge Water Company supplies water services to the city,[248] while Anglian Water provides sewerage services.[249] For the supply of electricity, Cambridge is part of the East of England region, for which the distribution network operator is UK Power Networks.[250] The city has no power stations, though a five-metre wind turbine, part of a Cambridge Regional College development, can be seen in King's Hedges.[251] The Cambridge Electric Supply Company had provided the city with electricity since the early twentieth century from Cambridge power station. Upon nationalisation of the electricity industry in 1948 ownership passed to the British Electricity Authority and later to the Central Electricity Generating Board. Electricity connections to the national grid rendered the small 7.26 megawatt (MW) coal fired power station redundant. It closed in 1965 and was subsequently demolished; in its final year of operation it delivered 2771 MWh of electricity to the city.[252]

Following the Public Libraries Act 1850 the city's first public library, located on Jesus Lane, was opened in 1855.[253] It was moved to the Guildhall in 1862,[253] and is now located in the Grand Arcade shopping centre. The library was reopened in September 2009,[254] after having been closed for refurbishment for 33 months, more than twice as long as was forecast when the library closed for redevelopment in January 2007.[254][255] As of 2018 the city contains six public libraries, run by the County Council.[256]

The Cambridge City Cemetery is located to the north of Newmarket Road.

Religion

[edit]Cambridge has a number of churches, some of which form a significant part of the city's architectural landscape. Like the rest of Cambridgeshire it is part of the Anglican Diocese of Ely.[257] Great St Mary's Church has the status of "University Church".[258] Many of the university colleges contain chapels that hold services according to the rites and ceremonies of the Church of England, while the chapel of St Edmund's College is Roman Catholic.[259] The city also has a number of theological colleges training clergy for ordination into a number of denominations, with affiliations to both the University of Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin University.

Cambridge is in the Roman Catholic Diocese of East Anglia and is served by the large Gothic Revival Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church at the junction of Hills Road and Lensfield Road, St Laurence's on Milton Road, St Vincent De Paul Church on Ditton Lane and by the church of St Philip Howard, in Cherry Hinton Road.[260]

There is a Russian Orthodox church under the Diocese of Sourozh who worship at the chapel of Westcott House,[261] the Greek Orthodox Church holds services at the purpose-built St Athanasios church under the Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain,[262] while the Romanian Orthodox Church share St Giles' with the Church of England.[263]

There are two Methodist churches in the city. Wesley Methodist Church was built in 1913, and is located next to Christ's Pieces. The Castle Street Methodist Church is the oldest of the two, having been built in 1823, and was formerly a Primitive Methodist church.

There are three Quaker Meetings in Cambridge, located on Jesus Lane, Hartington Grove, and a Meeting called "Oast House" that meets in Pembroke College.[264]

An Orthodox synagogue and Jewish student centre is located on Thompson's Lane, operated jointly by the Cambridge Traditional Jewish Congregation and the Cambridge University Jewish Society, which is affiliated to the Union of Jewish Students.[265][266] The Beth Shalom Reform synagogue which previously met at a local school,[267] opened a purpose-built synagogue in 2015.[268] There is also a student-led egalitarian minyan which holds services on Friday evenings.

Cambridge Central Mosque is the main place of worship for Cambridge's community of around 4,000 Muslims.[269][270] Opened in 2019, it is described as Europe's first eco-friendly mosque[271] and is the first purpose-built mosque within the city. The Abu Bakr Jamia Islamic Centre on Mawson Road and the Omar Faruque Mosque and Cultural Centre in Kings Hedges are additional places of Muslim worship.[272][273][274]

Cambridge Buddhist Centre, which belongs to Triratna Buddhist Community, was opened in the former Barnwell Theatre on Newmarket Road in 1998.[275] There are also several local Buddhist meditation groups from various Buddhist including Samatha Trust and Buddha Mettā Society.[276] A Hindu shrine was opened in 2010 at the Bharat Bhavan Indian cultural centre off Mill Road.[277][278]

A Sikh community has met in the city since 1982, and a Gurdwara was opened in Arbury in 2013.[279][280]

Twinned cities

[edit]Cambridge is twinned with two cities. Like Cambridge, both have universities and are also similar in population; Heidelberg, Germany since 1965,[281] and Szeged, Hungary since 1987.[281]

Panoramic gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of bridges in Cambridge

- List of churches in Cambridge

- Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies

- Category:Buildings and structures in Cambridge

- Category:Organisations based in Cambridge

- Category:People from Cambridge

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ All Saints, Holy Sepulchre, Holy Trinity, St Andrew the Great, St Andrew the Less, St Bene't, St Botolph, St Clement, St Edward, St Giles, St Mary the Great, St Mary the Less, St Michael, and St Peter

- ^ Weather station is located 0.8 miles (1.3 km) from the Cambridge city centre.

- ^ Weather station is located 3 miles (4.8 km) from the Cambridge city centre.

References

[edit]- ^ "Your council". Cambridge City Council. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Cambridge Local Authority (E07000008)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Cambridge". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "Population and household estimates, England and Wales: Census 2021 – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "United Kingdom: Countries and Major Urban Areas". citypopulation.de. 16 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2024. (2021 census)

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2023: Top Global Universities". Top Universities. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Cairns, Richard (1 October 2011). "What it takes to make it to Oxbridge". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Papworth heart and lung specialist hospital to move". BBC News. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Bronze Age site is found in city". BBC News. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "A brief history of Cambridge". Cambridge City Council. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Gray, Ronald D; Stubbings, Derek (2000). Cambridge Street-Names: Their Origins and Associations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-521-78956-1.

- ^ Henley, John (28 August 2009). "The Roman foundations of Cambridge". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

'What's interesting about Cambridge is that with these tracts of land bequeathed to the university, you have a lot of preserved green space coming in close to the city centre,' says Chris Evans, head of the Cambridge unit. 'It hasn't been developed in the intervening centuries. There are iron-age and Roman farmsteads literally every 200–300 metres.'

- ^ "Schoolgirls unearth Roman village under College garden". University of Cambridge. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

Large amounts of Roman pottery convinced both Dr Hills and Dr Lewis that they had dug through to the remains of a 2,000-year-old settlement, significant because it suggests that the Roman presence at Newnham was far more considerable than previously thought.

- ^ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- ^ Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. Archived 21 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Toovey (London), 1844.

- ^ Bishop Ussher believed the listing to refer to the Cambridge in Gloucestershire.[17]

- ^ Burnham, Barry C; Wacher, John (1990). The Small Towns of Roman Britain. London: B T Batsford.

- ^ a b c d Roach, J.P.C., ed. (1959). "The city of Cambridge: Medieval History". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2011 – via Institute of Historical Research.

- ^ In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, cited by Roach.[20]

- ^ A Dictionary, english-latin, and latin-english containing all things necessary for the translating of either language into the other By Elisha Coles · 1679

- ^ A Restoration of the Ancient Modes of Bestowing Names on the Rivers, Hills, Vallies, Plains, and Settlements of Britain by Gilbert Dyer Publication date 1805 (page 242)

- ^ Chance, F. (13 November 1869). "Cambridge". Notes and Queries. 4. London: Bell & Daldy: 401–404. OCLC 644126889. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Brooke, Christopher Nugent Lawrence; Riehl Leader, Damien (1988). A History of the University of Cambridge. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–10 [10]. ISBN 0-521-32882-9. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ a b Roach, J.P.C., ed. (1959). "The City of Cambridge: Constitutional History". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012 – via Institute of Historical Research.

- ^ Roach, J.P.C., ed. (1959). "The City of Cambridge: Churches". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3, the City and University of Cambridge. London: Victoria County History. pp. 123–132. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Bailey, Simon (18 December 2009). "The Hanging of the Clerks in 1209". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "University and Colleges: A Brief History". University of Cambridge. 7 February 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "About the College". Peterhouse College. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 141–43, 73–9. ISBN 978-0-230-27816-5. OL 28086241M.

- ^ a b Ziegler, Philip; Platt, Colin (1998). The Black Death (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-14-027524-7.

- ^ Atkinson, Thomas (1897). Cambridge, Described and Illustrated: Being a Short History of the Town and University. London: Macmillan. p. 41. OCLC 1663499. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

The Ward beyond the Bridge, that is, all the town on the Castle side of the river, appears to have been almost entirely destroyed. Most of the people in the parish of All Saints' in Castro died and those that escaped left the neighbourhood for other parishes.

- ^ Herlihy, David (1997). The Black Death and the Transformation of the West. European History. Harvard University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-674-07613-6. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ a b "History of the Chapel". King's College, Cambridge. 13 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Pennick, Nigel (9 January 2012). Secrets of King's College Chapel. Karnac Books. p. 3.

- ^ Roach, J. P. C., ed. (1959). "The city of Cambridge: Public health". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3, the City and University of Cambridge. London: Victoria County History. pp. 101–108. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Cambridgeshire > Natural History > Cam Valley Walk > Stage 7". BBC Cambridgeshire. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "The city of Cambridge – Modern history | A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge (1959)". 1959. pp. 15–29. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "The city of Cambridge: Modern history | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d Roach, J. P. C., ed. (1959). "The city of Cambridge: Economic history". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012 – via Institute of Historical Research.

- ^ a b Roach, J. P. C., ed. (1959). A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3. London: Victoria County History. pp. 109–111. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Roach, J. P. C., ed. (1959). "The city of Cambridge". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge. Victoria Couinty History. pp. 1–2 – via Institute of Historical Research.

- ^ Brigham, Allan; Wiles, Colin (2006), Bringing it all back home: Changes in Housing and Society 1966–2006, Chartered Institute of Housing, Eastern Branch, archived from the original on 20 December 2016, retrieved 27 April 2016

- ^ Wright, A. P. M.; Lewis, C.P., eds. (1989). "Chesterton: Introduction". A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 9: Chesterton, Northstowe, and Papworth Hundreds. Victoria History of the Counties of England. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 5–13. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ Shott, Rupert (2009). Rowan's Rule: the biography of the Archbishop. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-340-95433-1. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Christ's Lane". Land Securities. n.d. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Derek Taunt – Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 23 July 2004. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority Order 2017", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2017/251, retrieved 13 June 2023

- ^ "Cambridgeshire and Peterborough make devolution history – Politics – Cambridge Independent". 31 January 2017. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Historic England, "Guildhall (1268372)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 4 January 2018

- ^ "Council offices". Cambridge City Council. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "Ordnance Survey". Election maps. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales: Appendix 4. 1835. p. 2185. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "Ceremonial maces, 1207 charter and the city's coat of arms". Cambridge City Council. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "The mayors of Cambridge". Cambridge City Council. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Parliamentary Papers: Volume 26. 1837. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Municipal Corporations Act. 1835. p. 456. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Board's Provisional Orders Confirmation (No. 15) Act 1889". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Roach, J. P. C., ed. (1959). A History of the County of Cambridge: Volume 3. London: Victoria County History. pp. 101–108. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Board's Provisional Orders Confirmation (No. 10) Act 1911". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "Cambridge Municipal Borough". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "No. 39201". The London Gazette. 13 April 1951. p. 2067.

- ^ "The English Non-metropolitan Districts (Definition) Order 1972", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1972/2039, retrieved 31 May 2023

- ^ "Cambridge (England, United Kingdom)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ a b c "SUDS Design and Adoption Guide" (PDF). 20 December 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b "England's Geology – Cambridgeshire". Natural England. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "CB1 development". Cambridgshire County Council. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Accordia wins top architectural prize" (Press release). Cambridge City Council. 15 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Vision". Clay Farm. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Home". Trumpington Meadows Land Company. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Air Pollution in Cambridge". Cambridge City Council. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Cambridge, England Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Cambridge University Computer Laboratory Digital Technology Group". Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Weather Station, Cambridge University Computer Laboratory Digital Technology Group". Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Perring, Franklyn (16 June 1960). "Mapping the Distribution of Flowering Plants". New Scientist: 1525. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Climate & Soils". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

Cambridge is in the driest region of Britain and has a more continental climate than most of Britain.

- ^ "Our strategy". Cambridge Water. 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

We live in one of the driest areas of the UK. The East of England's rainfall of conditions is only half the national average and Cambridge is one of the driest parts of this region.

- ^ "Climate and Soils". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "NIAB weather data". Met Office. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Hot semi-arid (steppe) climate". www.mindat.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Wettest year since records began". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "UK Climate: July 2008". Met Office. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Anomaly details for Station Cambridge (B. GDNS): Maximum value of daily maximum temperature, August 2007". European Climate Assessment and Dataset. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Hottest day of each year from 1875". Trevor Harley. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "New official highest temperature in UK confirmed". Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Climatology details for station CAMBRIDGE (B. GDNS): Summer days (TX > 25 °C)". European Climate Assessment and Dataset. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Climatology details for station CAMBRIDGE (B. GDNS): Maximum value of daily maximum temperature". European Climate Assessment and Dataset. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Botanic Garden Extremes 1931–60". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "8 December 1879". Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Coldest temperatures of winter so far". Met Office News Blog. 11 February 2012. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "22nd Jan 2013 Temperatures". Met Office News Blog. 22 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "December 2010". Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Cambridge 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Climatology details for station CAMBRIDGE (B. GDNS): Frost days (TN < 0 °C)". European Climate Assessment and Dataset. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Climatology details for station CAMBRIDGE (B. GDNS): Minimum value of daily minimum temperature". European Climate Assessment and Dataset. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Indices Data - Cambridge (B. Gdns) Station 1639". KNMI. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Cambridgeniab 1991–2020 averages". Station, District and regional averages 1981–2010. Met Office. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Extreme Minimum Temperature". Starlings Roost Weather. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire & Peterborough (September 2006). Cambridge City Nature Conservation Strategy "Enhancing Biodiversity" (PDF) (Report). Cambridge City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Cambridge City Local Nature Reserves". Cambridge City Council. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Cooper, Anthony J. "The Origins of the Cambridge Green Belt" (PDF). www.cambridge.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Green belt final" (PDF). www.eastcambs.gov.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.