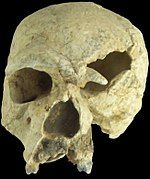

Steinheim skull

Original skull and holotype of the obsolete "H. steinheimensis" | |

| Common name | Steinheim skull |

|---|---|

| Species | Neanderthal or Homo heidelbergensis |

| Age | 300,000 years |

| Place discovered | Germany |

| Date discovered | 24 July 1933 |

The Steinheim skull is a fossilized skull of a Homo neanderthalensis[1] or Homo heidelbergensis found on 24 July 1933 near Steinheim an der Murr, Germany.[2]

It is estimated to be between 250,000 and 350,000 years old. The skull is slightly flattened and has a cranial capacity between 950 and 1280 cc.[3] Sometimes referred to as Homo steinheimensis in older literature, the original fossil is housed in the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, Germany. Some believe that the Steinheim skull may have belonged to an adult female due to its gracile nature.[4]

Classification

[edit]The "primitive man of Steinheim" is a single find. The designation "Steinheim skull" can be seen as a reference to the location of the fossil, but in no way identifies with a certain taxon. The skull shows characteristics of both H. heidelbergensis and Neanderthals. It is therefore classified by most paleoanthropologists to H. heidelbergensis and is believed to be a transitional form of H. heidelbergensis to Neanderthals. This has sometimes been referred to as "pre-Neanderthal.” [5][6] The inner ear of the fossil has a feature in which Neanderthals and H. sapiens differ. The location of the semicircular canals of the inner ear in the temporal bone of the skull base is similar to the situation in Neanderthals, while the semicircular canals of the older H. erectus, as with H. sapiens, are closer.[7]

Until the late 1980s, the fossil was sometimes referred to as H. sapiens steinheimensis. During this time Neanderthals were also referred to as H. sapiens neanderthalensis. Today, however, many paleoanthropologists classify Neanderthals and modern humans as separate species, with H. heidelbergensis their possible last common ancestor (LCA). Therefore that two distinct species are to be considered: H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens.

A 2016 study by Chris Stringer found Homo heidelbergensis to have not been the common ancestor of Neanderthals and humans, being instead placed entirely on the Neanderthal side of the tree along with Denisovans (close relatives of the Neanderthals) and the Steinheim skull, which was classified as an early Neanderthal fossil.[1] Taking this into account, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthals needs to be dated even further back, e. g. to Homo erectus, see Neanderthal §Evolution. Sequencing of genome (aDNA) and proteome (ancient protein) of further human fossils has to be done in order to shed light on the relation of H. heidelbergensis and the Steinheim skull to the pre-neanderthal "Neandersovans", the proposed LCA of Neanderthals and Denisovans.

A 2021 study by Chris Stringer found Steinheim sits as a sole sister to a group containing H. antecessor and H. longi, plus H. sapiens. Together they are considered as sister to the Neanderthals.[8]

Discovery

[edit]Prior to discovery of the Steinheim skull in the gravel pit, many objects such as bones of elephants, rhinos and wild horses had been unearthed. Therefore, the archaeologists excavating the site were already sensitized to possible skeletal remains in the quarry. Fritz Berckhemer traveled on the same day of the skull's discovery and reviewed the still hidden skull in the wall. The next day, together with Max Bock, he began the careful excavation. It was clear, on the basis of the shape and dimensions of the skull, that it was not a monkey, as had initially been suspected. It turned out to be a human skull from the Pleistocene. The skull was roughly cleaned, hardened and plastered so it would arrive safe and sound in the Museum of Natural History.[6]

The find in Steinheim turned up no other artifacts. There were no artifacts from the people as well as no other skeletal remains found. There were also no tools such as stone tools or bone implements discovered at the site. It can be assumed, however, that the hominin would have been capable of creating tools and using them for different purposes. For example, evidence of this can be found around the same time frame of “Swanscombe man", where they found some fist wedges from the Acheulean tool culture.[2][6]

Brain tumor

[edit]

The investigations completed at the Eberhard Karls University of Tuebingen in 2003 by Alfred Czarnetzki, Carsten M. Pusch and Erwin Schwaderer, showed that the owner of the skull suffered from a meningioma, which is an arachnoid tumor.[9] Meningiomas are a diverse set of tumors that arise from the meninges, which is the membranous layers surrounding the central nervous system.[10]

The slow-growing tumor had a size of 51 mm × 43 mm × 25 mm and a volume of 29 ml (1 imp fl oz; 1 US fl oz). It is believed that this tumor may have caused headaches. It is also possible that no neurological deficiencies were suffered, due to the slow growing nature of meningiomas.[9] Whether the tumor should be considered the cause of death cannot be determined from the remains. Having the rest of the skeleton would be necessary for further investigation into a possible cause of death. Meningiomas are very rare with roughly 2 out of 100,000 causing symptoms, so finding evidence of one in such ancient remains is a very exciting discovery.[11] It is the earliest evidence of a meningioma tumor on record.

See also

[edit]- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stringer, Chris (2016-07-05). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1698). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ a b "Steinheim skull | hominin fossil". Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ^ Prossinger, Hermann; Seidler, Horst; Wicke, Lothar; Weaver, Dave; Recheis, Wolfgang; Stringer, Chris; Müller, Gerd B. (2003). "Electronic removal of encrustations inside the Steinheim cranium reveals paranasal sinus features and deformations, and provides a revised endocranial volume estimate". The Anatomical Record. 273B (1): 132–42. doi:10.1002/ar.b.10022. PMID 12833273.

- ^ "Homo heidelbergensis - Australian Museum". australianmuseum.net.au. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Hublin: Die Sonderevolution der Neandertaler. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Juli 1998, Seite 56 ff.

- ^ a b c Reinhard Ziegler: 4 Millionen Jahre Mensch. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Mai 1999, Seite 130 ff.

- ^ Chris Stringer: The Origin of Our Species. Penguin / Allen Lane, 2011, S. 60. ISBN 978-1846141409.

- ^ Ni, Xijun; Ji, Qiang; Wu, Wensheng; Shao, Qingfeng; Ji, Yannan; Zhang, Chi; Liang, Lei; Ge, Junyi; Guo, Zhen; Li, Jinhua; Li, Qiang; Grün, Rainer; Stringer, Chris (2021-08-28). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. ISSN 2666-6758. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ a b Czarnetzki, A; Schwaderer, E; Pusch, CM (2003). "Fossil record of meningioma". Lancet. 362 (9381): 408. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14044-5. PMID 12907030. S2CID 3018162.

- ^ Cushing, Harvey (1922-10-01). "The Meningiomas (dural Endotheliomas): Their Source, and Favoured Seats of Origin". Brain. 45 (2): 282–316. doi:10.1093/brain/45.2.282. ISSN 0006-8950.

- ^ idw-online vom 11. August 2003: Tübinger Forscher finden erstmals Schädeltumor bei frühen Menschen.

Abbildung des Schädels (Memento vom 16. Oktober 2008 im Internet Archive)

External links

[edit] Media related to Steinheim skull at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Steinheim skull at Wikimedia Commons