Third Portuguese Republic

Portuguese Republic República Portuguesa (Portuguese) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "A Portuguesa" "The Portuguese" | |

Location of Portugal (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Lisbon 38°46′N 9°9′W / 38.767°N 9.150°W |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised regional languages | Mirandese[note 1] |

| Nationality (2022)[3] |

|

| Religion (2021)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Portuguese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic[5] |

| Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa | |

| Luís Montenegro | |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Republic |

| Establishment | |

• County | 868 |

| 24 June 1128 | |

• Kingdom | 25 July 1139 |

| 5 October 1143 | |

| 23 September 1822 | |

• Republic | 5 October 1910 |

| 25 April 1974 | |

| 25 April 1976[a] | |

| 1 January 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 92,212 km2 (35,603 sq mi)[7] (109th) |

• Water (%) | 1.2 (2015)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 115.4/km2 (298.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2023) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (42nd) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC (WET) UTC−1 (Atlantic/Azores) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (WEST) UTC (Atlantic/Azores) |

| Note: Continental Portugal and Madeira use WET/WEST; the Azores are 1 hour behind. | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +351 |

| ISO 3166 code | PT |

| Internet TLD | .pt |

| |

| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Third Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: Terceira República Portuguesa) is a period in the history of Portugal corresponding to the current democratic regime installed after the Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974, that put an end to the paternal autocratic regime of Estado Novo of António de Oliveira Salazar and Marcelo Caetano. It was initially characterized by constant instability and was threatened by the possibility of a civil war during the early post-revolutionary years. A new constitution was drafted, censorship was prohibited, free speech declared, political prisoners were released and major Estado Novo institutions were closed. Eventually the country granted independence to its African colonies and began a process of democratization that led to the accession of Portugal to the EEC (today's European Union) in 1986.

Background

[edit]

In Portugal, 1926 marked the end of the First Republic, in a military coup that established an authoritarian government called Estado Novo, that was led by António de Oliveira Salazar until 1968, when he was forced to step down due to health problems. Salazar was succeeded by Marcelo Caetano. The government faced many internal and external problems, including the Portuguese Colonial War.

On 25 April 1974 a mostly bloodless coup of young military personnel forced Marcelo Caetano to step down. Most of the population of the country soon supported this uprising. It was called the Carnation Revolution because of the use of the carnation on soldiers' rifles as a symbol of peace. This revolution was the beginning of the Portuguese Third Republic. The days after the revolution saw widespread celebration for the end of 48 years of dictatorship and soon exiled politicians like Álvaro Cunhal and Mário Soares returned to the country for the celebration of May Day, in what became a symbol of the country's regained freedom.

After the revolution

[edit]After the fall of the Estado Novo, differences began to emerge on which political direction the country should take, including among the military. The revolution was mainly the result of the work of a group of young officers unified under the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA). Within this group, there were several different political views, among them those represented by Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho and considered to be the more radical wing of the movement and those represented by Ernesto Melo Antunes, considered to be the more moderate one.

In addition to that, to ensure the success of the uprising, the MFA looked for support among the conservative sections of the military that had been disaffected with the Caetano government, chief among which were the former Head of the Armed Forces, General Francisco da Costa Gomes, and General António de Spínola. Both had been expelled from the Estado-Maior-General das Forças Armadas for criticizing the government.

The differing political views came to be broadly represented by three main informal groups, which included both military and civilians. However, even within these groups that shared similar political views there were considerable disagreements.

- the conservatives: within the military, represented by Costa Gomes and Spínola and within the MFA by Melo Antunes. Its civilian representatives were politicians that had been part of the Ala Liberal (Liberal Wing) of the Assembleia Nacional (National Assembly) that called for a transition to democracy, among them the future Prime-Ministers Francisco de Sá Carneiro and Francisco Pinto Balsemão.

- the socialists: that were in favour of creating a social-democratic state like those of Western Europe and were mainly represented by the Socialist Party and its leader Mário Soares.

- the communists: that were in favour of creating a communist state with an economic system similar to those of the Warsaw Pact countries. The main representative of this group within the military and the MFA was Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, while the main political party included in this group was the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), led by Álvaro Cunhal.

2000s

[edit]In 2001, António Guterres, the Prime Minister since 1995, resigned after the local elections, and after legislative elections on the following year, José Manuel Barroso was appointed as the new prime minister.[13] In July 2004, Prime Minister Barroso resigned as prime minister to become President of the European Commission.[14] He was succeeded by Pedro Santana Lopes, as leader of Social Democratic Party and Prime Minister of Portugal.[15] In 2005, Socialists got a landslide victory in early elections. Socialist Party leader Jose Socrates became the new prime minister after the elections.[16] In 2009 elections Socialist Party won re-election but lost its overall majority. In October 2009, Prime Minister Jose Socrates formed a new minority government.[17]

The Euro

[edit]On 1 January 2002, Portugal adopted the euro as its currency in place of the escudo.[18]

Euro 2004

[edit]Euro 2004 was held across Portugal. The final match was won by Greece against Portugal. Several new stadia were built or rebuilt for the event. This event granted Portugal an opportunity to show its hosting abilities to the rest of the world.[19]

2006 presidential elections

[edit]The Portuguese presidential election were held on 22 January 2006 to elect a successor to the incumbent President Jorge Sampaio, who was prevented from running for a third consecutive term by the Constitution of Portugal. The result was a victory in the first round for Aníbal Cavaco Silva of the Social Democratic Party, the former prime minister, who won 50.59 per cent of the vote in the first round, just over the majority required to avoid a runoff election. Voter turnout was 62.60 per cent of eligible voters.[20]

Economic difficulties

[edit]From 2007 to 2008 onwards, Portugal was severely affected by the European sovereign-debt crisis. The legacy of considerable borrowing from earlier years became an almost unsustainable debt for the Portuguese economy, bringing the country to the verge of bankruptcy by 2011. This resulted in urgent measures to address structural problems in the economy, raise taxes and reduce public-sector spending. Increasing unemployment also led to increased emigration.

2010s

[edit]Portugal suffered from a severe economic crisis between 2009 and 2016.[21]

In January 2011, Anibal Cavaco Silva was easily re-elected as President of the Republic of Portugal for a second five-year term in the first round of the election.[22]

In 2011, Portugal applied for EU assistance, as the third European Union country after Greece and Ireland, to cope with its budget deficit caused by the financial crisis.[23]

In June 2011, center-right Passos Coelho became the new prime minister of the financially-troubled country, succeeding former Socialist Prime Minister Jose Socrates. The Social Democrat Party, led by Pedro Passos Coelho, won the parliamentary election earlier same month.[24]

Austerity budgets included spending cuts and higher taxes, which caused worsening living standards in the country and higher unemployment to above 16%.[25]

In October 2015 parliamentary elections, the governing centre-right coalition of Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho won narrowly, but the coalition lost its absolute majority in parliament.[26]

The new minority government led by Passos Coelho was soon toppled in a parliamentary vote. The 11-day-old government was the shortest-lived national government in the Portuguese history. In November 2015, The Socialist leader Antonio Costa became Portugal's prime minister, after forming an alliance with Communist, Green and Left Bloc parties.[27]

In January 2016, centre-right politician Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa was elected as the new president of Portugal.[28]

In October 2016, former Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Guterres was officially appointed as the next United Nations Secretary-General. He took office on 1 January 2017, when Ban Ki-moon's second five-year term ended.[29]

In October 2019, Prime Minister Antonio Costa won the parliamentary election. His Socialist party won the most votes, but it did not get the absolute majority in parliament. The party continued its pact with two far-left parties - the Left Bloc and the Communists. Portugal's economy had grown above the EU average and many cuts to public sector had been reversed.[30]

2020s

[edit]In January 2021, Portugal's centre-right president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa won re-election, after taking 60.7% of the votes in the first round of the election.[31]

In June 2021, United Nations General Assembly unanimously elected Antonio Guterres to a second five-year term as secretary-general.[32]

The ruling Socialist Party, led by Prime Minister António Costa, won an outright majority in the January 2022 snap general election. The Socialist Party won 120 seats in the 230 seat parliament, defeating the right-wing to form the XXIII Constitutional Government of Portugal.[33]

On 2 April 2024, the new center-right minority government, led by Prime Minister Luís Montenegro, took office, resulting from the slim victory of the Democratic Alliance in the snap election.[34]

Timeline

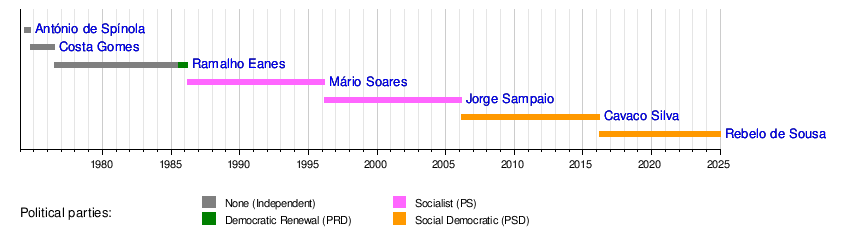

[edit]Presidents of the Republic (1974–present)

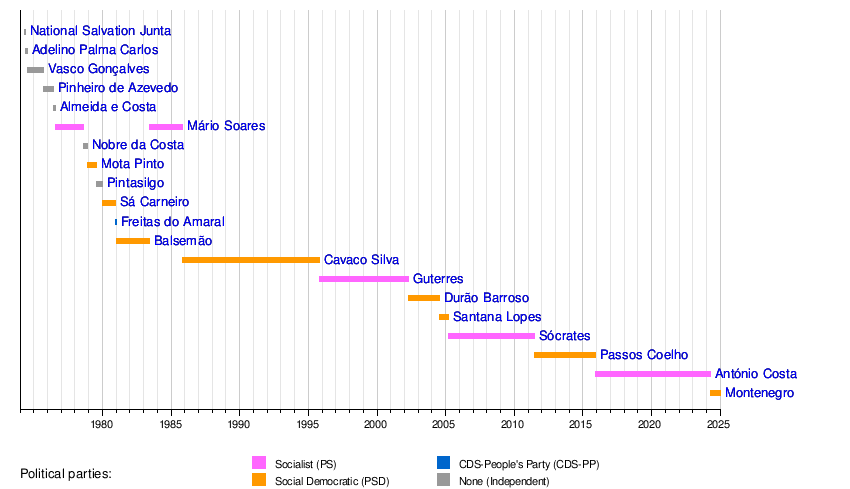

Prime Ministers (1974–present)

Incumbent leaders

[edit]Economic data since 1980

[edit]GDP growth %

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP)

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Source:[35]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Portuguese Constitution adopted in 1976 with several subsequent minor revisions, between 1982 and 2005.

- ^ Mirandese, spoken in the region of Terra de Miranda, was officially recognized in 1999 (Lei n.° 7/99 de 29 de Janeiro),[1] awarding it an official right-of-use.[2] Portuguese Sign Language is also recognized.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Reconhecimento oficial de direitos linguísticos da comunidade mirandesa (Official recognition of linguistic rights of the Mirandese community)". Centro de Linguística da Universidade de Lisboa (UdL). Archived from the original on 18 March 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ a b The Euromosaic study, Mirandese in Portugal, europa.eu – European Commission website. Retrieved January 2007. Link updated December 2015

- ^ "SEF - Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras". Portal Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Censos 2021. Católicos diminuem, mas ainda são mais de 80% dos portugueses". RTP. 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Constitution of Portugal, Preamble:

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ (in Portuguese)"Superfície Que municípios têm maior e menor área?". Pordata. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "População residente ultrapassa os 10,6 milhões - 2023". ine.pt. INE. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ "Censos 2021 - Principais tendências ocorridas em Portugal na última década". Statistics Portugal - Web Portal. 23 November 2022. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Portugal)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "A taxa de risco de pobreza aumentou para 17,0% em 2022 - 2023". www.ine.pt. INE. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. p. 288. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Nash, Elizabeth (18 March 2002). "Right gains power by narrow margin in Portugal". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 2 October 2011. [dead link]

- ^ "Barroso Appointed EU Commission President – DW – 06/30/2004". dw.com.

- ^ "Santana Lopes is new PM". Portugal Resident. 21 July 2004.

- ^ "José Sócrates | World Leaders Forum". worldleaders.columbia.edu.

- ^ "Portugal profile - Timeline". BBC News. 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Portugal and the euro". European Commission - European Commission.

- ^ "History". UEFA.com. 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Anibal Cavaco Silva wins the presidential election in the first round". www.robert-schuman.eu.

- ^ Pettinger, Tejvan (26 February 2018). "Portugal Economic Crisis". Economics Help.

- ^ "Anibal Cavaco Silva is easily re-elected as President of the Republic of Portugal". www.robert-schuman.eu.

- ^ "Timeline: Portugal". 22 March 2012 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Center-Right Leader Passos Coelho Named Portugal's New PM « VOA Breaking News".

- ^ "Portugal passes latest austerity budget". BBC News. 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Portugal centre-right wins re-election despite bailout". BBC News. 5 October 2015.

- ^ Lisbon, Agence France-Presse in (25 November 2015). "Portugal gets Antonio Costa as new PM after election winner only lasted 11 days". the Guardian.

- ^ "Portugal's new president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa wants to 'heal wounds'". euronews. 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Portugal's Antonio Guterres elected UN secretary-general". BBC News. 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Portugal election: Socialists win without outright majority". BBC News. 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Portugal's centre-right president re-elected but far right gains ground". the Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 25 January 2021.

- ^ "Guterres re-elected for second-term as UN Secretary General". euronews. 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Portugal election: Socialists win unexpected majority". BBC News. 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Portugal's new government aims to outmanoeuvre radical populist rivals". euronews. 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: October 2022". www.imf.org. Retrieved 29 October 2022.