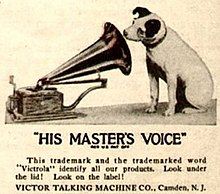

His Master's Voice

His Master's Voice (1899) by Francis Barraud | |

| Owner |

|

|---|---|

His Master's Voice is an English painting by Francis Barraud in 1899 that depicts a dog named Nipper listening to a wind-up disc gramophone whilst tilting his head. The painting was sold to William Barry Owen of London's Gramophone Company, and would also be adopted as the trademark and logo for their United States affiliate, the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1901.

In 1929, the Victor Talking Machine Company was acquired by RCA, gaining control of the His Master's Voice trademarks in the U.S. and Canada, as well as Japan until they were divested to JVC during World War II, eventually becoming Victor Entertainment.[1] In 1931, the UK's Gramophone Company merged with Columbia Graphophone to form EMI; EMI would then own the His Master's Voice (HMV) chain of stores. In February 1998, HMV became HMV Group plc, a separate public company in February 1998 that operated across Europe, Australia and Asia, with EMI no longer in control of the 'His Master's Voice' trademark.[2] HMV's retail operations in Hong Kong and Singapore, and subsequent 'His Master's Voice' trademarks, were later sold off.[3] HMV in the United Kingdom would go into administration in December 2018 with JD Sports acquiring the 'HMV' trademark, but Hilco Capital retaining the 'His Master's Voice' trademark for Europe and Australia.[4]

History

[edit]The phrase was coined in the late 1890s from the title of a painting by English artist Francis Barraud, which depicted a dog named Nipper listening to a wind-up disc gramophone and tilting his head.[5] In the original, unmodified 1898 painting, the dog was listening to a cylinder phonograph.[6]

In early 1899, Francis Barraud applied for copyright of the original painting using the descriptive working title Dog looking at and listening to a Phonograph. He was unable to sell the work to any cylinder phonograph company.[citation needed] The painting had been originally offered to James Hough, manager of Edison-Bell in London, but he declined, saying "dogs don't listen to phonographs".[citation needed] William Barry Owen, the American founder of the Gramophone Company in England, offered to purchase the painting for £100, under the condition that Barraud modify it to show one of their disc machines.[7] Barraud complied and the image was first used on the company's catalogue from December 1899. As the trademark gained in popularity, several additional copies were subsequently commissioned from the artist for various corporate purposes.[8]

In 1967, EMI converted the HMV label into an exclusive classical music label and dropped its POP series of popular music. HMV's pop series artists' roster was moved to Columbia Graphophone and Parlophone and licensed American pop record deals to Stateside Records.[9]

In the 1970s, an award was created with a copy of the statue of the dog and gramophone, His Master's Voice, cloaked in bronze, and was presented by EMI Records to artists, music producers, and composers in recognition of selling more than 1,000,000 records.[citation needed]

In 1990, the globalised market for the compact disc resulted in EMI retiring the HMV label in favour of EMI Classics, a name that could be used worldwide; however, Morrissey's recordings were issued on the HMV label until 1992.[citation needed]

In June 2003, the formal His Master's Voice trademark transfer took place from EMI Records to HMV Media Group plc.[10]

In January 2017, Warner Music Group (who purchased EMI in September 2012) launched Warner Classics digital efforts as 'Dog and Trumpet' due to not having the 'His Master's Voice' trademark rights.[11][12] Most reissues of former His Master's Voice-pop material previously controlled by EMI are now re-issued on Warner's Parlophone label.[13]

See also

[edit]- List of HMV POP artists

- La voce del padrone, the Italian version of His Master's Voice

- Saregama India Ltd, the Indian version who used to trade as His Master's Voice

References

[edit]- ^ "ビクターエンタテインメント | Victor Entertainment". ビクターエンタテインメント | Victor Entertainment (in Japanese). Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Joseph, Seb (15 January 2013). "HMV: Brand Timeline". Marketing Week. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "The fight for Nipper: takeaways from HMV's trademark battle in Singapore". www.worldtrademarkreview.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Ong Sheng Li, Gabriel (18 April 2023). "HMV Brand Pte. Ltd. v Yongfeng Trade Co., Limited" (PDF). Intellectual Property Office of Singapore. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sommese, Andrea; Miklósi, Ádám; Pogány, Ákos; Temesi, Andrea; Dror, Shany; Fugazza, Claudia (2022). "An exploratory analysis of head-tilting in dogs". Animal Cognition. 25 (3): 701–705. doi:10.1007/s10071-021-01571-8. PMC 9107419. PMID 34697669.

- ^ Wetzel, Corryn, Why Do Dogs Tilt Their Heads? New Study Offers Clues, Smithsonian, 3 November 2021

- ^ Rye, Howard (2002). Kernfeld, Barry (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc. p. 249. ISBN 1-56159-284-6.

- ^ "The Nipper Saga". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- ^ Billboard. 1967. Retrieved 28 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Trade Mark Details as at 28 February 2013: HMV Group plc". Patent.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ "Gramophone". reader.exacteditions.com. May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017.

- ^ "Claude Debussy – Vladimir Horowitz: Complete HMV Recordings 1930–1951". Warner Classics. 12 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018.

- ^ "At Abbey Road". Amazon.

Further reading

[edit]- Barnum, Fred (1991). His Master's Voice in America.

- Southall, Brian (1996). The Story of the World's Leading Music Retailer: HMV 75, 1921–1996.

External links

[edit]- Musée des ondes Emile Berliner

- List of releases at 45worlds.com

- His Master's Voice discography at Discogs

- Musée des ondes Emile Berliner – Montréal Archived 16 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine