Butoh

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

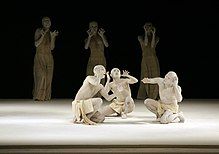

Butoh (舞踏, Butō) is a form of Japanese dance theatre that encompasses a diverse range of activities, techniques and motivations for dance, performance, or movement. Following World War II, butoh arose in 1959 through collaborations between its two key founders, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. The art form is known to "resist fixity"[1] and is difficult to define; notably, founder Hijikata Tatsumi viewed the formalisation of butoh with "distress".[2] Common features of the art form include playful and grotesque imagery, taboo topics, and extreme or absurd environments. It is traditionally performed in white body makeup with slow hyper-controlled motion. However, with time butoh groups are increasingly being formed around the world, with their various aesthetic ideals and intentions.

History

[edit]

Butoh first appeared in post-World War II Japan in 1959, under the collaboration of Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, "in the protective shadow of the 1950s and 1960s avant-garde".[3] A key impetus of the art form was a reaction against the Japanese dance scene then, which Hijikata felt was overly based on imitating the West and following traditional styles like Noh. Thus, he sought to "turn away from the Western styles of dance, ballet and modern",[2] and to create a new aesthetic that embraced the "squat, earthbound physique... and the natural movements of the common folk".[2] This desire found form in the early movement of "ankoku butō" (暗黒舞踏). The term means "dance of darkness", and the form was built on a vocabulary of "crude physical gestures and uncouth habits... a direct assault on the refinement (miyabi) and understatement (shibui) so valued in Japanese aesthetics."[4]

The first butoh piece, Forbidden Colors (禁色, Kinjiki) by Tatsumi Hijikata, premiered at a dance festival in 1959. It was based on the novel of the same name by Yukio Mishima. It explored the taboo of homosexuality and ended with a live chicken being held between the legs of Kazuo Ohno's son Yoshito Ohno, after which Hijikata chased Yoshito off the stage in darkness. Mainly as a result of the audience outrage over this piece, Hijikata was banned from the festival, establishing him as an iconoclast.

The earliest butoh performances were called (in English) "Dance Experience". In the early 1960s, Hijikata used the term "Ankoku-Buyou" (暗黒舞踊, dance of darkness) to describe his dance. He later changed the word "buyo", filled with associations of Japanese classical dance, to "butoh", a long-discarded word for dance that originally meant European ballroom dancing.[5]

In later work, Hijikata continued to subvert conventional notions of dance. Inspired by writers such as Yukio Mishima (as noted above), Comte de Lautréamont, Antonin Artaud, Jean Genet and Marquis de Sade, he delved into grotesquerie, darkness, and decay. At the same time, Hijikata explored the transmutation of the human body into other forms, such as those of animals. He also developed a poetic and surreal choreographic language, butoh-fu (舞踏譜, fu means "notation" in Japanese), to help the dancer transform into other states of being.

The work developed beginning in 1960 by Kazuo Ohno with Tatsumi Hijikata was the beginning of what now is regarded as "butoh". In Nourit Masson-Sékiné and Jean Viala's book Shades of Darkness,[6] Ohno is regarded as "the soul of butoh", while Hijikata is seen as "the architect of butoh". Hijikata and Ohno later developed their own styles of teaching. Students of each style went on to create different groups such as Sankai Juku, a Japanese dance troupe well known to fans in North America.

Students of these two artists have been known to highlight the differing orientations of their masters. While Hijikata was a fearsome technician of the nervous system influencing input strategies and artists working in groups, Ohno is thought of as a more natural, individual, and nurturing figure who influenced solo artists.

Starting in the early 1980s, butoh experienced a renaissance as butoh groups began performing outside Japan for the first time; at this time the style was marked by "full body paint (white or dark or gold), near or complete nudity, shaved heads, grotesque costumes, clawed hands, rolled-up eyes and mouths opened in silent screams."[7][8] Sankai Juku was a touring butoh group; during one performance by Sankai Juku, in which the performers hung upside down from ropes from a tall building in Seattle, one of the ropes broke, resulting in the death of a performer. The footage was played on national news, and butoh became more widely known in America through the tragedy.[9] A PBS documentary of a butoh performance in a cave without an audience further broadened awareness of butoh in America.

In the early 1990s, Koichi Tamano performed atop the giant drum of San Francisco Taiko Dojo inside Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, in an international religious celebration.[citation needed]

There is a theatre in Kyoto, Japan, called the Kyoto Butoh-kan, which attempts to be dedicated to regular professional butoh performances.[10][11]

Debate

[edit]There is much discussion about who should receive the credit for creating butoh. As artists worked to create new art in all disciplines after World War II, Japanese artists and thinkers emerged from economic and social challenges that produced an energy and renewal of artists, dancers, painters, musicians, writers, and all other artists.

A number of people with few formal connections to Hijikata began to call their own idiosyncratic dance "butoh". Among these are Iwana Masaki (岩名雅紀), and Teru Goi.[12] Although all manner of systematic thinking about butoh dance can be found, perhaps Iwana Masaki most accurately sums up the variety of butoh styles:

While 'Ankoku Butoh' can be said to have possessed a very precise method and philosophy (perhaps it could be called 'inherited butoh'), I regard present-day butoh as a 'tendency' that depends not only on Hijikata's philosophical legacy but also on the development of new and diverse modes of expression. The 'tendency' that I speak of involved extricating the pure life which is dormant in our bodies.[13]

Hijikata is often quoted saying what opposition he had to a codified dance: "Since I believe neither in a dance teaching method nor in controlling movement, I do not teach in this manner."[14] However, in the pursuit and development of his own work, it is only natural that a "Hijikata" style of working and, therefore, a "method" emerged. Both Mikami Kayo and Maro Akaji have stated that Hijikata exhorted his disciples not to imitate his own dance when they left to create their own butoh dance groups. If this is the case, then his words make sense: There are as many types of butoh as there are butoh choreographers.

New Butoh

[edit]In 2000 Sayoko Onishi established in Palermo, Italy where she founded the International Butoh Academy at the presence of master and butoh founder Yoshito Ohno. Sayoko Onishi and Yoshito Ohno are credited as being the first butoh choreographers to speak about New Butoh style. The academy name was changed to New Butoh School in 2007. In 2018 the New Butoh School established in Ruvo di Puglia, Italy.[1]

Butoh exercises

[edit]Most butoh exercises use image work to varying degrees: from the razorblades and insects of Ankoku Butoh, to Dairakudakan's threads and water jets, to Seiryukai's rod in the body. There is a general trend toward the body as "being moved", from an internal or external source, rather than consciously moving a body part. A certain element of "control vs. uncontrol" is present through many of the exercises.[15]

Conventional butoh exercises sometimes cause great duress or pain but, as Kurihara points out, pain, starvation, and sleep deprivation were all part of life under Hijikata's method,[5] which may have helped the dancers access a movement space where the movement cues had terrific power. It is also worth noting that Hijikata's movement cues are, in general, much more visceral and complicated than anything else since.

Most exercises from Japan (with the exception of much of Ohno Kazuo's work) have specific body shapes or general postures assigned to them, while almost none of the exercises from Western butoh dancers have specific shapes. This seems to point to a general trend in the West that butoh is not seen as specific movement cues with shapes assigned to them such as Ankoku Butoh or Dairakudakan's technique work, but rather that butoh is a certain state of mind or feeling that influences the body directly or indirectly.

Hijikata did in fact stress feeling through form in his dance, saying, "Life catches up with form,"[16] which in no way suggests that his dance was mere form. Ohno, though, comes from the other direction: "Form comes of itself, only insofar as there is a spiritual content to begin with."[16]

The trend toward form is apparent in several Japanese dance groups, who recycle Hijikata's shapes and present butoh that is only body-shapes and choreography[17] which would lead butoh closer to contemporary dance or performance art than anything else. A good example of this is Torifune Butoh-sha's recent works.[15]

Iwana Masaki, a butoh dancer whose work shies away from all elements of choreography, states:

I have never heard of a butoh dancer entering a competition. Every butoh performance itself is an ultimate expression; there are not and cannot be second or third places. If butoh dancers were content with less than the ultimate, they would not be actually dancing butoh, for real butoh, like real life itself, cannot be given rankings.[13]

Defining butoh

[edit]Critic Mark Holborn has written that butoh is defined by its very evasion of definition.[18] The Kyoto Journal variably categorizes butoh as dance, theater, "kitchen," or "seditious act."[19] The San Francisco Examiner describes butoh as "unclassifiable".[20] The SF Weekly article "The Bizarre World of Butoh" was about former sushi restaurant Country Station, in which Koichi Tamano was "chef" and Hiroko Tamano "manager". The article begins, "There's a dirty corner of Mission Street, where a sushi restaurant called Country Station shares space with hoodlums and homeless drunks, a restaurant so camouflaged by dark and filth it easily escapes notice. But when the restaurant is full and bustling, there is a kind of theater that happens inside…"[21] Butoh frequently occurs in areas of extremes of the human condition, such as skid rows, or extreme physical environments, such as a cave with no audience, remote Japanese cemetery, or hanging by ropes from a skyscraper in front of the Washington Monument.[22]

Hiroko Tamano considers modeling for artists to be butoh, in which she poses in "impossible" positions held for hours, which she calls "really slow Butoh".[citation needed] The Tamano's home seconds as a "dance" studio, with any room or portion of yard potentially used. When a completely new student arrived for a workshop in 1989 and found a chaotic simultaneous photo shoot, dress rehearsal for a performance at Berkeley's Zellerbach Hall, workshop, costume making session, lunch, chat, and newspaper interview, all "choreographed" into one event by Tamano, she ordered the student, in broken English, "Do interview." The new student was interviewed, without informing the reporter that the student had no knowledge what butoh was. The improvised information was published, "defining" butoh for the area public. Tamano then informed the student that the interview itself was butoh, and that was the lesson.[citation needed] Such "seditious acts," or pranks in the context of chaos, are butoh.[18]

While many approaches to defining butoh—as with any performative tradition—will focus on formalism or semantic layers, another approach is to focus on physical technique. While butoh does not have a codified classical technique rigidly adhered to within an authoritative controlled lineage, Hijikata Tatsumi did have a substantive methodical body of movement techniques called Butoh Fu. Butoh Fu can be described as a series of cues largely based on incorporating visualizations that directly affect the nervous system, producing qualities of movement that are then used to construct the form and expression of the dance. This mode of engaging the nervous system directly has much in common with other mimetic techniques to be found in the history of dance, such as Lecoq's range of nervous system qualities, Decroux's rhythm and density within movement, and Zeami Motokiyo's qualitative descriptions for character types.

Influence

[edit]Teachers influenced by more Hijikata style approaches tend to use highly elaborate visualizations that can be highly mimetic, theatrical, and expressive. Teachers of this style include Yukio Waguri, Yumiko Yoshioka, Minako Seki and Koichi and Hiroko Tamano, founders of Harupin-Ha Butoh Dance Company.[23]

There have been many unique groups and performance companies influenced by the movements created by Hijikata and Ohno, ranging from the highly minimalist of Sankai Juku to very theatrically explosive and carnivalesque performance of groups like Dairakudakan.

International

[edit]Many Nikkei (or members of the Japanese diaspora), such as Japanese Canadians Jay Hirabayashi of Kokoro Dance, Denise Fujiwara, incorporate butoh in their dance or have launched butoh dance troupes.

More notable European practitioners, who have worked with butoh and avoided the stereotyped 'butoh' languages which some European practitioners tend to adopt, take their work out of the sometimes closed world of 'touring butoh' and into the international dance and theatre scenes include SU-EN Butoh Company (Sweden), Marie-Gabrielle Rotie,[24] Kitt Johnson (Denmark), Vangeline (France), and Katharina Vogel (Switzerland). Such practitioners in Europe aim to go back to the original aims of Hijikata and Ohno and go beyond the tendency to imitate a ' master' and instead search within their own bodies and histories for 'the body that has not been robbed' (Hijikata).

Marie-Gabrielle Rotie has studied Butoh since 1993, and was fortunate to study in Asbsestos Kan with the widow of Tatusmi Hijikata - Motofuji, and also with Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno in their studio, as well as many other Butoh choreographers who have now departed, including Carlotta Ikeda and Ko Muorubushi. She established and organised Butoh in the UK[25] since 1994 and was the first European artist to receive notable funding support for her pioneering work informed by Butoh into mainstream dance organisations in UK including the Royal Opera House, The Place Theatre and Royal National Theatre (she was choreographer and chorus performer for 'Bacchai' for Sir Peter Hall).[26] Her choreographer in film includes for The Northman (2022) and movement choreography for Nosferatu (2024/5)[27] for film director Robert Eggers, had enormous positive press responses, particularly for her work with lead actress Lily Rose Depp. [28]

LEIMAY (Brooklyn) emerged 1996-2005 from the creative work of Shige Moriya, Ximena Garnica, Juan Merchan, and Zachary Model at the space known as CAVE. LEIMAY has organized and run diverse programs including, the NY Butoh Kan Training Initiative which later became the NY Butoh Festival; Vietnamese Artist in Residency; NY Butoh Kan Training Initiative which turned into the NY Butoh Kan Teaching Residency and now is called LEIMAY Ludus Training). A key element of LEIMAY's work has become transformation of specific spaces. In this way, the space – at times a body, environment or object – and the body – at times dancer, actor, performer or object – are fundamental to LEIMAY's work.

Eseohe Arhebamen, a princess of the Kingdom of Ugu and royal descendant of the Benin Empire, is the first indigenous and native-born African butoh performer.[29] She invented a style called "Butoh-vocal theatre" which incorporates singing, talking, mudras, sign language, spoken word, and experimental vocalizations with butoh after the traditional dance styles of the Edo people of West Africa.[30] She is also known as Edoheart.[31][32]

COLLAPSINGsilence Performance Troupe (San Francisco) was established and co-founded by Indra Lowenstein and Terrance Graven in 1992 and was active until 2001. They were a movement-based troupe that incorporated butoh, shibari, ecstatic trance states, and Odissi. They designed all of their costumes, props, puppets, and site-specific installations, while collaborating with live musicians such as Sharkbait, Hollow Earth, Haunted by Waters, and Mandible Chatter. In 1996, they were featured at The International Performance Art Festival and also performed at Asian American Dance Performances, San Francisco Butoh Festival, Theatre of Yugen, The Los Angeles County Exposition (L.A.C.E.), Stanford University, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, the beginning years at Burning Man, and various other venues creating multi-media dance performances.

In 1992, Bob DeNatale founded the Flesh & Blood Mystery Theater to spread the art of butoh. Performing throughout the United States, Flesh & Blood Mystery Theater was a regular participant in the San Francisco Butoh Festival of which DeNatale was an Associate Producer. DeNatale's other butoh credits include performing in the film Oakland Underground (2006) and touring Germany and Poland with Ex…it! ' 99 International Dance Festival.

In 2018, Patruni Sastry redesigned Butoh Natyam with the blend of Indian classical dance Bharatanayam with the pedagogy of butoh and presented/performed across 200 shows in India. in later years Patruni also used Butoh as a part of their drag practice.[33][34][35]

Butoh in popular culture

[edit]

Music videos

[edit]Music videos featuring Butoh or butoh-style performance

- Lebanon Hanover 'Come Kali Come' featuring Marie-Gabrielle Rotie

- Madonna's "Nothing Really Matters"

- Kent's "Musik non stop"

- The Finnish band Black Crucifixion's 2013 "Millions of Twigs Guide Your Way Through the Forest" features Ken Mai.

- Machine Head's song "Catharsis".[36]

- Rammstein's "Mein Teil" features the band member Oliver Riedel performance

- Matt Elliott's song "Something About Ghosts" features Gyohei Zaitsu

- Dir En Grey's 2003 "Obscure" features women dressed in Geisha attire with blackened teeth, wearing butoh-style face paint and performing bodily movements/facial expressions similar to those found in butoh.

- Foals' "Inhaler" by director Dave Ma with movement choreography by Marie-Gabrielle Rotie

- The Weeknd's "Belong to the World"

- Blackhaine's "Be Right Now / We Walk Away"[37]

- Vegyn - "Nauseous / Devilish (feat. JPEGMAFIA)"[38]

Other popular culture

[edit]Exploitation film director Teruo Ishii hired Hijikata to play the role of a Doctor Moreau-like reclusive mad scientist in his 1969 horror film Horrors of Malformed Men.[39] The role was mostly performed as dance. The film has remained largely unseen in Japan for forty years because it was viewed as insensitive to the handicapped.[40]

The 1992 Ron Fricke documentary film Baraka features scenes of Butoh performance.

The 1995 Hal Hartley film Flirt features performance choreographed by Yoshito Ohno.

In Bust A Groove 2, a video game released for the PlayStation in 2000, the dance moves of the hidden boss character Pander are based on Butoh.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa used Butoh movement for actors in the 2001 film Kairo.

The influence of Butoh has also been felt heavily in the J-Horror movie genre, forming the basis for the appearance of the ghosts in seminal 2002 film Ju-on: The Grudge.[41]

The 2008 Doris Dörrie film Cherry Blossoms features a Bavarian widower on a journey to Japan to grieve for his wife and develops an understanding of Butoh style performance.

Sopor Aeternus and the Ensemble of Shadows, the musical project of Anna-Varney Cantodea.

Richard Armitage cited the dance form as an inspiration for his animalistic portrayal of the villain Francis Dolarhyde (the "Red Dragon") in the third season of Hannibal.[42]

The Brisbane-based artist, KETTLE, attributes their performance art pieces, Otherwise (2001)[43] and The Australian National Anthem (2001),[44] to Butoh.

Butoh dancers play the coven of witches featured in the climax of the 2015 folk horror film The Witch.

In 2019, Japanese-American indie rock musician Mitski began incorporating Butoh-inspired choreography into her live performances, including "highly stylized, sometimes unsettling gestures," developed with performance artist and movement coach Monica Mirabile.[45][46][47]

Butoh dance is a recurring theme in the 2020 Taiwanese movie Wrath of Desire.[48]

Choreography by Marie-Gabrielle Rotie for the Robert Eggers films The Northman (2022) and Nosferatu.[citation needed]

Taiwanese-American performer Nymphia Wind created an outfit inspired by Butoh for the Dancing Queen runway on the season 16 "Snatch Game" episode of RuPaul's Drag Race (2024).[49]

Butoh artists

[edit]Japanese

[edit]- Juju Alishina[50]

- Ushio Amagatsu

- Carlotta Ikeda

- Eiko & Koma

- Tadashi Endo

- Maureen Fleming

- Mushimaru Fujieda

- Anzu Furukawa

- GooSayTen

- Tatsumi Hijikata

- Mitsutaka Ishii

- Masaki Iwana

- Sankai Juku

- Katsura Kan

- Akira Kasai

- Akaji Maro

- Ko Murobushi

- Nakajima Natsu

- Kazuo Ohno

- Yoshito Ohno

- Mitsuyo Uesugi

- Minoru Hideshima

- Atsushi Takenouchi

- Hal Tanaka

- Seiji Tanaka

- Bishop Yamada[51]

- Yumiko Yoshioka[52][53]

- MUTSUMINEIRO

Non-Japanese

[edit]- Marie-Gabrielle Rotie

- Yumino Seki

- Katarina Vogel

- Blackhaine[38]

- Edoheart

- Maureen Fleming

- Simona Orinska

- Grigory Glazunov

- Andrada Jichici

- Patruni Sastry[33]

- Adam Koan[54]

- Maria Lappa

- Rhizome Lee[55][56]

- Natalia Zhestovskaya

Notes, references and sources

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Waychoff, Brianne. "Butoh, Bodies and Being". Kaleidoscope. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Sanders, Vicki (Autumn 1988). "Dancing and the Dark Soul of Japan: An Aesthetic Analysis of "Butō"". Asian Theatre Journal. 5 (2): 152. JSTOR 25161489.

- ^ Sanders, Vicki (Autumn 1988). "Dancing and the Dark Soul of Japan: An Aesthetic Analysis of "Butō"". Asian Theatre Journal. 5 (2): 148–163. JSTOR 25161489.

- ^ Sanders, Vicki (Autumn 1988). "Dancing and the Dark Soul of Japan: An Aesthetic Analysis of "Butō"". Asian Theatre Journal. 5 (2): 149. JSTOR 25161489.

- ^ a b Kurihara, Nanako. The Most Remote Thing in the Universe: Critical Analysis of Hijikata Tatsumi's Butoh Dance. Diss. New York U, 1996. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1996. 9706275

- ^ "Publications". nouritms.fr. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Loke, Margarett (1 November 1987). "Butoh: Dance of Darkness". The New York Times.

- ^ Tanaka, Nobuko (23 January 2016). "'Crazy Camel' helps butoh over the hump". The Japan Times.

- ^ ""The Dance: Sankai Juku Opens", Anna Kisselgoff, New York Times". Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- ^ "New butoh venue aims for intimacy | The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ "World's first dedicated Butoh theater to open in Kyoto". Japan Today. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Kuniyoshi, Kazuko. An Overview of the Contemporary Japanese Dance Scene. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation, 1985; Viala, Jean. Butoh: Shades of Darkness. Tokyo: Shufunotomo, 1988.

- ^ a b Iwana, Masaki. The Dance and Thoughts of Masaki Iwana. Tokyo: Butoh Kenkyuu-jo Hakutou-kan, 2002.

- ^ quoted in Viala 186

- ^ a b Coelho, Abel. "A Compilation of Butoh Exercises" Honolulu: U H Dept. of Theatre and Dance 2008

- ^ a b Ohno, Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno. Kazuo Ohno's World from Without and Within. Trans. John Barrett. Middletown: Wesleyan U P, 2004.

- ^ Viala 100

- ^ a b "Dance Kitchen, Dustin Leavitt, Kyoto Journal #70". Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- ^ ""Dance Kitchen", Dustin Leavitt, Kyoto Journal #70". Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- ^ "Bizarre and Beautiful Butoh at Lab", Allan Ulrich, San Francisco Examiner, Dec 1, 1989.

- ^ ""The Bizarre World of Butoh", Bernice Yeung, San Francisco Weekly, July 17-23, 2002, cover and p15-22".

- ^ Butoh, Mark Holburn and Ethan Hoffman, Sadev Books, 1987

- ^ "LINE掲示板は危険※安全なLINE交換方法はコレだ!". www.harupin-ha.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Article title[usurped], http://www.butohuk.com

- ^ "about". Butoh Uk. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ "In Search of Greek Theatre: Bacchae (1973) and Bacchai (2002) | National Theatre". www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ "Nosferatu (2024 film)", Wikipedia, 15 January 2025, retrieved 15 January 2025

- ^ Schofield, Blanca (31 December 2024). "How I taught Lily-Rose Depp to act possessed in Nosferatu". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ "Nigeriansk Butoh", Anna, Swedish Palms, 2011 Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Performance Studies". nyu.edu. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ ""Art/Trek NYC - Edoheart", NYC Media, The City of New York, 2012". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ "U of C". www.ipccalgary.ca. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b https://www.telegraphindia.com/my-kolkata/people/patruni-sastry-the-dancer-who-brought-drag-to-hyderabad/cid/1946447 [bare URL]

- ^ "Patruni's Story". 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Integrating Bharatanatyam and Japan's Butoh with grace". 24 December 2018.

- ^ "Video Premiere: MACHINE HEAD's 'Catharsis'". Blabbermouth. 8 December 2018.

- ^ Blackhaine (1 February 2024). Blackhaine - Be Right Now / We Walk Away. Retrieved 17 October 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "Blackhaine: the bleak, brilliant Lancashire rapper-dancer hired by Kanye West". The Guardian. 18 January 2022. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Mes, Tom. "Midnight Eye review: The Horror of Malformed Men (Edogawa Rampo Zenshu Kyofu Kikei Ningen, 1969, Teruo ISHII)". www.midnighteye.com. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "Reviews: HORRORS OF MALFORMED MEN DVD Review". Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Through A Glass Darkly: Exclusive interview with director Shimizu Takashi from the UK special edition DVD

- ^ "'Hannibal' Red Dragon". The Hollywood Reporter. 24 July 2015.

- ^ "Otherwise, by KETTLE (2001), Brisbane". YouTube. 26 August 2006. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- ^ "The Australian National Anthem, by KETTLE (2001), Brisbane". YouTube. 26 August 2006.

- ^ Horn, Olivia (20 August 2020). "Mitski Shows Off Her Moves". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Talbot, Margaret (8 July 2019). "On the Road with Mitski". The New Yorker. No. July 8 & 15, 2019. Condé Nast. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Austin City Limits (9 January 2020). "Mitski on Austin City Limits "Happy"". Vimeo. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Wrath of Desire Movie Behind the Scenes: Dance".

- ^ "'RuPaul's Drag Race' Season 16, Episode 8 power ranking: Comic Ru-lief". Xtra Magazine. 25 February 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Butoh with Juju Alishina". www.dansejaponaise.fr.

- ^ 小菅, 隼人. "Bodies heading for the north: A dialogue with butoh dancer Bishop Yamada".

- ^ Fraleigh (2010), pp. 235−236

- ^ van Hensbergen, Rosa (2018). "German Butoh since the Late 1980s: Tadashi Endo, Yumiko Yoshioka, and Minako Seki". In Baird, Bruce; Candelario, Rosemary (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Butoh Performance. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. pp. 276–284. doi:10.4324/9781315536132-30. ISBN 9781315536118.

- ^ Murthy, Neeraja (21 December 2018). "Memories carved out of shadows". The Hindu.

- ^ "Dancing in the shadows". 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Theatre: Bringing the performing art form butoh to Bengaluru | Bengaluru News". The Times of India. February 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Alishina, Juju (2015). Butoh dance training : secrets of Japanese dance through the Alishina method (paperback ed.). Singing Dragon. ISBN 978-1-84819-276-8. / Butoh Dance Training (ebook ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley. 21 July 2015. ISBN 978-0-85701-226-5. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Mikami, Kayo (12 April 2016). The Body as a Vessel. St Nicholas-at-Wade: Ozaru Books. ISBN 978-0-9931587-4-2.

- Fraleigh, Sondra (2010). Butoh: metamorphic dance and global alchemy. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252090136.

External links

[edit]- Butoh UK

- butoh.de: photography, text and information about butoh in English and German

- Hokkaido Butoh Festival (Japan)

- New Butoh School (Italy)

- Torifune Butoh-sha (on Google Arts & Culture)