High-Rise (novel)

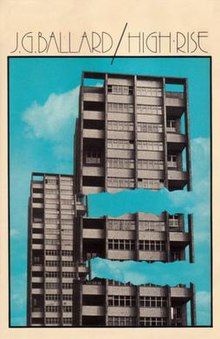

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | J. G. Ballard |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian, thriller |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1975 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 204 |

| ISBN | 0-224-01168-5 |

| OCLC | 1993557 |

| 823/.9/14 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.B1893 Hi PR6052.A46 |

| Preceded by | Concrete Island (1974) |

| Followed by | The Unlimited Dream Company (1979) |

High-Rise is a 1975 novel by British writer J. G. Ballard.[1] The story describes the disintegration of a luxury high-rise building as its affluent residents gradually descend into violent chaos. As with Ballard's previous novels Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974), High-Rise inquires into the ways in which modern social and technological landscapes could alter the human psyche in provocative and hitherto unexplored ways. It was adapted into a film of the same name, in 2015, by director Ben Wheatley.

Plot

[edit]Following his divorce, doctor and medical-school lecturer Robert Laing moves into his new apartment on the 25th floor of a recently completed high-rise building on the outskirts of London. This tower block provides its affluent tenants all the conveniences and commodities that modern life has to offer: a supermarket, bank, restaurant, hair salon, swimming pools, a gymnasium, its own school, and high-speed lifts. Its cutting-edge amenities allow the occupants to gradually become uninterested in the outside world, providing them with accommodation and a secure environment.

Laing meets fellow tenants Charlotte Melville, a secretary who lives one floor above him, and Richard Wilder, a documentary film-maker who lives with his family on the building's lower floors. Life in the high-rise begins to degenerate quickly, as minor power failures and petty grievances among neighbours and between rival floors escalate into an orgy of violence. Skirmishes become frequent throughout the building as whole floors of tenants try to claim lifts and hold them for their own. Groups gather to defend their rights to the swimming pools, and party-goers attack "enemy floors" to raid and vandalise them. The lower, middle, and upper floors of the building gradually stratify into distinct groups.

It does not take long for the occupants to ignore social restraints, abandoning life outside the building and devoting their time to the escalation of violence inside; people quit their jobs, and families stay indoors permanently, losing all sense of time. As the amenities of the high-rise break down and bodies begin to pile up, no one considers leaving or alerting the authorities, instead exploring the newly-found urges and desires engendered by the building's disintegration. As Laing navigates the new environment, Wilder sets out to reach floor 40—the top of the building—and finally confront the building's architect, Anthony Royal.

Legacy

[edit]High-Rise was known to be among Joy Division singer Ian Curtis's favourite books.[2] The book has been cited as an influence upon the 1987 Doctor Who serial Paradise Towers.[3] Hawkwind used the book as the basis for a song of the same name on their 1979 album PXR5.[4][5]

Some critics have pointed out the thematic similarities between the novel and Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg's early film Shivers, a.k.a. They Came from Within (1975). Aside from the fact that they both came out the same year, both the book and the film tell a story in which the tenants of a humongous, isolated hi-tech residential building wind up descending into an anarchic orgy of sex and violence. Although lacking in formal precision and narrative tightness, compared to Cronenberg's later, more mature films, it has been suggested that this is a truer (yet serendipitous) adaptation of the novel than Ben Wheatley's 2015 version. Cronenberg later undertook the challenging project of adapting into film Ballard's debut novel, Crash (1973), —a novel considered unfilmable up until then— about a subculture of people who fetishise car accidents. The 1996 film version stars James Spader, Holly Hunter and Elias Koteas.[6]

In a lecture on J. G. Ballard with John Gray, Will Self represented Withnail and I director Bruce Robinson's interpretation of the story which has "the unconscious, the car park of the building, penetrating the ego in the conquest of the super ego in the top of the building." He then stated that Ballard would have hated that interpretation, with Self preferring instead the interpretation that "Freudian ideas swirl and fail to coalesce," as they are "appropriated by individual mythomanes without actually reflecting an external reality."[7]

Canadian post-rock band Godspeed You! Black Emperor listed it on their recommended reading list to coincide with their appearance at and curation of the All Tomorrow's Parties festival in 2010.[8]

Artwork

[edit]The cover of the novel's first edition shows a high rise in Berlin's Hansaviertel designed by the German architect Hans Schwippert.

Film adaptation

[edit]For over 30 years, British producer Jeremy Thomas had wanted to do a film version of the book. It was nearly made in the late 1970s, with Nicolas Roeg directing from a script by Paul Mayersberg. Later attempts with Canadian film-maker Vincenzo Natali attached to write and direct also failed,[9][10] before the film adaptation was finally made in 2014.

With Jeremy Thomas producing, Ben Wheatley directing from a script by Amy Jump, and Tom Hiddleston starring in the lead role, [11][12] the film had its world première at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 13, 2015, and was widely released in early 2016.

References

[edit]- ^ J. G. Ballard; James Goddard (1976). J. G. Ballard, the First Twenty Years. Bran's Head Books Limited. p. 89. ISBN 9780905220031.

- ^ Savage, Jon (9 May 2008). "Controlled chaos". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ^ Newman, Kim (2009). "Doctor Who: Paradise Towers (1987)". The Kim Newman Archive. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen (20 April 2009). "What pop music tells us about JG Ballard". London: BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Sellars, Simon. "Flat block of two dimensions". Ballardian. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "David Cronenberg: Shivers". 11 April 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Water Shed – John Gray and Will Self – JG Ballard

- ^ "Book Club curated by Godspeed You! Black Emperor".

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (22 May 2009). "Vincenzo Natali's High Rise Is A Beautiful Skyscraper of Doom". Gizmodo. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Fear, David (20 September 2015). "Toronto 2015: Ben Wheatley on 'High-Rise' and Cult Filmmaking". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith (5 February 2014). "Tom Hiddleston will star in the movie adaptation of High-Rise!". io9. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (29 August 2013). "Ben Wheatley to direct JG Ballard's High-Rise for RPC". Screen Daily. Retrieved 15 December 2014.