High-explosive anti-tank

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

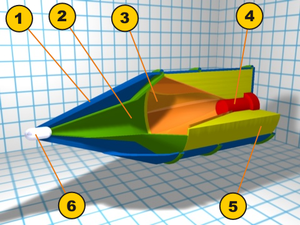

High-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) is the effect of a shaped charge explosive that uses the Munroe effect to penetrate heavy armor. The warhead functions by having an explosive charge collapse a metal liner inside the warhead into a high-velocity shaped charge jet; this is capable of penetrating armor steel to a depth of seven or more times the diameter of the charge (charge diameters, CD). The shaped charge jet armor penetration effect is purely kinetic in nature; the round has no explosive or incendiary effect on the armor.

Unlike standard armor-piercing rounds, a HEAT warhead's penetration performance is unaffected by the projectile's velocity, allowing them to be fired by lower-powered weapons that generate less recoil.

The performance of HEAT weapons has nothing to do with thermal effects, with HEAT being simply an acronym.

History

[edit]

HEAT warheads were developed during World War II, from extensive research and development into shaped charge warheads. Shaped charge warheads were promoted internationally by the Swiss inventor Henry Mohaupt, who exhibited the weapon before World War II. Before 1939, Mohaupt demonstrated his invention to British and French ordnance authorities. Concurrent development by the German inventors’ group of Cranz, Schardin, and Thomanek led to the first documented use of shaped charges in warfare, during the successful assault on the fortress of Eben Emael on 10 May 1940.

Claims for priority of invention are difficult to resolve due to subsequent historic interpretations, secrecy, espionage, and international commercial interest.[1]

The first British HEAT weapon to be developed and issued was a rifle grenade using a 63.5 millimetres (2.50 in) cup launcher on the end of the rifle barrel; the Grenade, Rifle No. 68 /AT which was first issued to the British Armed Forces in 1940. This has some claim to have been the first HEAT warhead and launcher in use. The design of the warhead was simple and was capable of penetrating 52 millimetres (2.0 in) of armor.[2] The fuze of the grenade was armed by removing a pin in the tail which prevented the firing pin from flying forward. Simple fins gave it stability in the air and, provided the grenade hit the target at the proper angle of 90 degrees, the charge would be effective. Detonation occurred on impact, when a striker in the tail of the grenade overcame the resistance of a creep spring and was thrown forward into a stab detonator.

By mid-1940, Germany introduced the first HEAT round to be fired by a gun, the 7.5 cm Gr.38 Hl/A, (later editions B and C) fired by the KwK.37 L/24 of the Panzer IV tank and the StuG III self-propelled gun . In mid-1941, Germany started the production of HEAT rifle-grenades, first issued to paratroopers and, by 1942, to the regular army units (Gewehr-Panzergranate 40, 46 and 61), but, just as did the British, soon turned to integrated warhead-delivery systems: In 1943, the Püppchen, Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust were introduced.

The Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck (tank fist and tank terror, respectively) gave the German infantryman the ability to destroy any tank on the battlefield from 50 to 150 meters with relative ease of use and training (unlike the British PIAT). The Germans made use of large quantities of HEAT ammunition in converted 7.5 cm Pak 97/38 guns from 1942, also fabricating HEAT warheads for the Mistel weapon. These so-called Schwere Hohlladung (heavy shaped charge) warheads were intended for use against heavily armored battleships. Operational versions weighed nearly two tons and were perhaps the largest HEAT warheads ever deployed.[3] A five-ton version code-named Beethoven was also developed.

Meanwhile, the British No. 68 AT rifle grenade was proving to be too light to deal significant damage, resulting in it rarely being used in action. Due to these limits, a new infantry anti-tank weapon was needed, and this ultimately came in the form of the "projector, infantry, anti-tank" or PIAT. By 1942, the PIAT had been developed by Major Millis Jefferis. It was a combination of a HEAT warhead with a spigot mortar delivery system. While cumbersome, the weapon allowed British infantry to engage armor at range for the first time. The earlier magnetic hand-mines and grenades required them to approach dangerously near.[4] During World War II the British referred to the Monroe effect as the "cavity effect on explosives".[5]

During the war, the French communicated Mohaupt's technology to the U.S. Ordnance Department, and he was invited to the US, where he worked as a consultant on the bazooka project.

The need for a large bore made HEAT rounds relatively ineffective in existing small-caliber anti-tank guns of the era. Germany worked around this with the Stielgranate 41, introducing a round that was placed over the end on the outside of otherwise obsolete 37 millimetres (1.5 in) anti-tank guns to produce a medium-range low-velocity weapon.

Adaptations to existing tank guns were somewhat more difficult, although all major forces had done so by the end of the war. Since velocity has little effect on the armor-piercing ability of the round, which is defined by explosive power, HEAT rounds were particularly useful in long-range combat where slower terminal velocity was not an issue. The Germans were again the ones to produce the most capable gun-fired HEAT rounds, using a driving band on bearings to allow it to fly unspun from their existing rifled tank guns. The HEAT round was particularly useful to them because it allowed the low-velocity large-bore guns used on their many assault guns to also become useful anti-tank weapons.

Likewise, the Germans, Italians, and Japanese had in service many obsolescent infantry guns, short-barreled, low-velocity artillery pieces capable of direct and indirect fire and intended for infantry support, similar in tactical role to mortars; generally an infantry battalion had a battery of four or six. High-explosive anti-tank rounds for these old infantry guns made them semi-useful anti-tank guns, particularly the German 150 millimetres (5.9 in) guns (the Japanese 70 mm Type 92 battalion gun and Italian 65 mm mountain gun also had HEAT rounds available for them by 1944 but they were not very effective).

High-explosive anti-tank rounds caused a revolution in anti-tank warfare when they were first introduced in the later stages of World War II. One infantryman could effectively destroy any existing tank with a handheld weapon, thereby dramatically altering the nature of mobile operations. During World War II, weapons using HEAT warheads were termed hollow charge or shape charge warheads.[5]

Post World War II

[edit]

The general public remained in the dark about shape charge warheads, even believing that it was a new secret explosive, until early 1945 when the US Army cooperated with the US monthly publication Popular Science on a large and detailed article on the subject titled "It makes steel flow like mud".[6] It was this article that revealed to the American public how the fabled bazooka actually worked against tanks and that the velocity of the rocket was irrelevant.

After the war, HEAT rounds became almost universal as the primary anti-tank weapon. Models of varying effectiveness were produced for almost all weapons from infantry weapons like rifle grenades and the M203 grenade launcher, to larger dedicated anti-tank systems like the Carl Gustav recoilless rifle. When combined with the wire-guided missile, infantry weapons were able to operate at long-ranges also. Anti-tank missiles altered the nature of tank warfare from the 1960s to the 1990s; due to the tremendous penetration of HEAT munitions, many post-WWII main battle tanks, such as the Leopard 1 and AMX-30, were deliberately designed to carry modest armour in favour of reduced weight and better mobility. Despite subsequent developments in vehicle armour, HEAT munitions remain effective to this day.

Design

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Penetration performance and effects

[edit]

The jet moves at hypersonic speeds in solid material and therefore erodes exclusively in the local area where it interacts with armor material. The correct detonation point of the warhead and spacing is critical for optimal penetration, for two reasons:

- If the HEAT warhead is detonated too near a target's surface, there is not enough time for the jet to fully form. That is why most modern HEAT warheads have what is called a standoff, in the form of an extended nose cap or probe in front of the warhead.

- The jet stretches, breaks apart and disperses during travel, reducing effectiveness. Depending on the quality of the HEAT warhead, this happens around 6 to 8 times the charge diameter for low quality and around 12 to 20 times the charge diameter for high quality warheads.[7] For example the 150 mm diameter warhead of the newer BGM-71 TOW (TOW 2) reaches a peak penetration of ~1000 mm RHA at 6.5x diameter (~1 m) and is down to ~500 mm RHA penetration at 19x diameter (~2.8 m).

An important factor in the penetration performance of a HEAT round is the diameter of the warhead. As the penetration continues through the armor, the width of the hole decreases leading to a characteristic fist to finger penetration, where the size of the eventual finger is based on the size of the original fist. In general, very early HEAT rounds could expect to penetrate armor of 150% to 250% of their diameters, and these numbers were typical of early weapons used during World War II. Since then, the penetration of HEAT rounds relative to projectile diameters has steadily increased as a result of improved liner material and metal jet performance. Some modern examples claim numbers as high as 700%.[8]

As for any antiarmor weapon, a HEAT round achieves its effectiveness through three primary mechanisms. Most obviously, when it perforates the armor, the jet's residual can cause great damage to any interior components it strikes. And as the jet interacts with the armor, even if it does not perforate into the interior, it typically causes a cloud of irregular fragments of armor material to spall from the inside surface. This cloud of behind-armor debris too will typically damage anything that the fragments strike. Another damage mechanism is the mechanical shock that results from the jet's impact and penetration. Shock is particularly important for such sensitive components as electronics.

Stabilization and accuracy

[edit]

Spinning imparts centrifugal force onto a warhead's jet, dispersing it and reducing effectiveness. This became a challenge for weapon designers: for a long time, spinning a shell was the most standard method to obtain good accuracy, as with any rifled gun.[9] Most hollow charge projectiles are fin-stabilized and not spin-stabilized.[10]

In recent years, it has become possible to use shaped charges in spin-stabilized projectiles by imparting an opposite spin on the jet so that the two spins cancel out and result in a non-spinning jet. This is done either using fluted copper liners, which have raised ridges, or by forming the liner in such a way that it has a crystalline structure which imparts spin to the jet.[11][12]

Besides spin-stabilization, another problem with any barreled weapon (that is, a gun) is that a large-diameter shell has worse accuracy than a small-diameter shell of the same weight. The lessening of accuracy increases dramatically with range. Paradoxically, this leads to situations when a kinetic armor-piercing projectile is more usable at long ranges than a HEAT projectile, despite the latter having a higher armor penetration. To illustrate this: a stationary Soviet T-62 tank, firing a (smoothbore) cannon at a range of 1000 meters against a target moving 19 km/h was rated to have a first-round hit probability of 70% when firing a kinetic projectile. Under the same conditions, it could expect 25% when firing a HEAT round.[13] This affects combat on the open battlefield with long lines of sight; the same T-62 could expect a 70% first-round hit probability using HEAT rounds on target at 500 meters.

Additionally, a warhead's diameter is restricted by a gun's caliber if it is contained within the barrel. In non-gun applications, when HEAT warheads are delivered with missiles, rockets, bombs, grenades, or spigot mortars, the warhead size is no longer a limiting factor. In these cases, HEAT warheads often seem oversized in relation to the round's body. Classic examples of this include the German Panzerfaust and Soviet RPG-7.

Variants

[edit]

Many HEAT-armed missiles today[when?] have two (or more) separate warheads (termed a tandem charge) to be more effective against reactive or multi-layered armor. The first, smaller warhead initiates the reactive armor, while the second (or other), larger warhead penetrates the armor below. This approach requires highly sophisticated fuzing electronics to set off the two warheads the correct time apart, and also special barriers between the warheads to stop unwanted interactions; this makes them cost more to produce.

The latest HEAT warheads, such as 3BK-31, feature triple charges: the first penetrates the spaced armor, the second the reactive or first layers of armor, and the third one finishes the penetration. The total penetration value may reach up to 800 millimetres (31 in).[14]

Some anti-armor weapons incorporate a variant on the shaped charge concept that, depending on the source, can be called an explosively formed penetrator (EFP), self-forging fragment (SFF), self-forging projectile (SEFOP), plate charge, or Misnay Schardin (MS) charge. This warhead type uses the interaction of the detonation waves, and to a lesser extent the propulsive effect of the detonation products, to deform a dish or plate of metal (iron, tantalum, etc.) into a slug-shaped projectile of low length-to-diameter ratio and project this towards the target at around two kilometers per second.

The SFF is relatively unaffected by first-generation reactive armor, it can also travel more than 1,000 cone diameters (CDs) before its velocity becomes ineffective at penetrating armor due to aerodynamic drag, or hitting the target becomes a problem. The impact of an SFF normally causes a large diameter, but relatively shallow hole (relative to a shaped charge) or, at best, a few CDs. If the SFF perforates the armor, extensive behind-armor damage (BAD, also called behind-armor effect (BAE)) occurs. The BAD is mainly caused by the high temperature and velocity armor and slug fragments being injected into the interior space and also overpressure (blast) caused by the impact.

More modern SFF warhead versions, through the use of advanced initiation modes, can also produce rods (stretched slugs), multi-slugs and finned projectiles, and this in addition to the standard short L to D ratio projectile. The stretched slugs are able to penetrate a much greater depth of armor, at some loss to BAD. Multi-slugs are better at defeating light or area targets and the finned projectiles have greatly enhanced accuracy. The use of this warhead type is mainly restricted to lightly armored areas of MBTs—the top, belly and rear armored areas, for example. It is well suited for use in the attack of other less heavily armored fighting vehicles (AFVs) and for breaching material targets (buildings, bunkers, bridge supports, etc.). The newer rod projectiles may be effective against the more heavily armored areas of MBTs.

Weapons using the SEFOP principle have already been used in combat; the smart submunitions in the CBU-97 cluster bomb used by the US Air Force and US Navy in the 2003 Iraq war used this principle, and the US Army is reportedly experimenting with precision-guided artillery shells under Project SADARM (Seek And Destroy Armor). There are also various other projectiles (BONUS, DM 642) and rocket submunitions (Motiv-3M, DM 642) and mines (MIFF, TMRP-6) that use the SFF principle.

Multipurpose

[edit]With the effectiveness of gun-fired single charge HEAT rounds being lessened, or even negated by increasingly sophisticated armoring techniques, a class of HEAT rounds termed high-explosive anti-tank multi-purpose, or HEAT-MP, has become more popular. These are HEAT rounds that are effective against older tanks and light armored vehicles but have improved fragmentation, blast and fuzing. This gives the projectiles an overall reasonable light armor and anti-personnel and material effect so that they can be used in place of conventional high-explosive rounds against infantry and other battlefield targets. This reduces the total number of rounds that need to be carried for different roles, which is particularly important for modern tanks like the M1 Abrams, due to the size of their 120 millimetres (4.7 in) rounds. The M1A1/M1A2 tank can carry only 40 rounds for its 120 mm M256 gun—the M60A3 Patton tank (the Abrams' predecessor), carried 63 rounds for its 105 millimetres (4.1 in) M68 gun. This effect is reduced by the higher first round hit rate of the Abrams with its improved fire control system compared to that of the M60.

Another variant of HEAT warheads surround the warhead with a conventional fragmentation casing, to increase its effectiveness against unarmored targets, while remaining effective in the anti-armor role. In some cases, this is merely a side effect of the armor-piercing design, whilst other designs specifically incorporate this dual role ability.

-

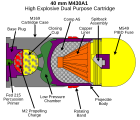

40×53 mm M430A1 HEDP grenade

-

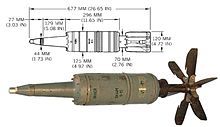

AGM-114 Hellfire missile with fragmentation sleeve around its shaped charge

Defense

[edit]Improvements to the armor of main battle tanks have reduced the usefulness of HEAT warheads by making effective man portable HEAT missiles heavier, although many of the world's armies continue to carry man-portable HEAT rocket launchers for use against vehicles and bunkers. In unusual cases, shoulder-launched HEAT rockets are believed to have shot down U.S. helicopters in Iraq.[15]

The reason for the ineffectiveness of HEAT munitions against modern main battle tanks can be attributed in part to the use of new types of armor. The jet created by the explosion of the HEAT round must be a certain distance from the target and must not be deflected. Reactive armor attempts to defeat this with an outward directed explosion under the impact point, causing the jet to deform and so greatly reducing penetrating power. Alternatively, composite armor featuring ceramics erode the liner jet faster than rolled homogeneous armor steel, the preferred material in constructing older armored fighting vehicles.

Spaced armor and slat armor are also designed to defend against HEAT rounds, protecting vehicles by causing premature detonation of the explosive at a relatively safe distance away from the main armor of the vehicle. Some cage defenses work by destroying the mechanism of the HEAT round.

Deployment

[edit]Helicopters have carried anti-tank guided missiles (ATGM) tipped with HEAT warheads since 1956.[citation needed] The first example of this was the use of the Nord SS.11 ATGM on the Aérospatiale Alouette II helicopter by the French Armed Forces. After then, such weapon systems were widely adopted by other nations.[citation needed]

On 13 April 1972—during the Vietnam War—Americans Major Larry McKay, Captain Bill Causey, First Lieutenant Steve Shields, and Chief Warrant Officer Barry McIntyre became the first helicopter crew to destroy enemy armor in combat. A flight of two AH-1 Cobra helicopters, dispatched from Battery F, 79th Artillery, 1st Cavalry Division, were armed with the newly developed M247 70 millimeter (2.8 in) HEAT rockets, which were yet untested in the theatre of war. The helicopters destroyed three T-54 tanks that were about to overrun a U.S. command post. McIntyre and McKay engaged first, destroying the lead tank.[16][page needed]

See also

[edit]- Electric armor

- High-explosive squash head

- Kinetic energy penetrator

- MAHEM

- Reactive armor

- Tandem-charge

Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Donald R. Kennedy, History of the Shaped Charge Effect: The First 100 Years Archived 2021-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, D. R. Kennedy & Associates, 1983

- ^ R F Eather, BSc & N Griffith, OBE MSc – Some Historical Aspects of the Development of Shaped Charges – Ministry of Defence, Royal Armament Research and Development Establishment – 1984 – page 6 – AD-A144 098

- ^ Article title[dead link] A Brief History of Shaped Charges - Defense Technical Information, pg. 9

- ^ Ian Hogg, Grenades and Mortars, Weapons Book #37, 1974, Ballantine Books

- ^ a b "The Bazooka's Grandfather". Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine Popular Science, February 1945, p. 66, 2nd paragraph.

- ^ "It makes steel flow like mud". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Johnsson, Fredrik (December 2012). "Shaped Charge Calculation Models for Explosive Ordnance Disposal Operations". ResearchGate.

- ^ Jane's Ammunition Handbook 1994, pp. 140–141, addresses the reported ≈700 mm penetration of the Swedish 106 3A-HEAT-T and Austrian RAT 700 HEAT projectiles for the 106 mm M40A1 recoilless rifle.

- ^ Singh, Sampooran (1960). "Penetration of Rotating Shaped Charges". J. Appl. Phys. 31 (3). American Institute of Physics Publishing: 578–582. Bibcode:1960JAP....31..578S. doi:10.1063/1.1735631. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ^ "Big Bullets for Beginners". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Held, Manfred. Spinning Jets from Shaped Charges with Flow Turned Liners. 12th International Symposium on Ballistics, San Antonio, TX, 30 Oct. - 1 Nov. 1990. Bibcode:1990ball.sympR....H.

- ^ Held, Manfred (November 2001). "Liners for shaped charges" (PDF). Journal of Battlefield Technology. 4 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-19. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ Jane's Armour and Artillery 1981–82, p. 55.

- ^ Vasiliy Fofanov – 125MM HEAT-FS rounds Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine (eng.)

- ^ Aviation Week Report[dead link]

- ^ Kelley, Michael (2011). Where We Were in Vietnam: A Comprehensive Guide to the Firebases and Military Installations of the Vietnam War. New York: L & R Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55571-689-9. OCLC 1102308963.