Hex (1973 film)

| Hex | |

|---|---|

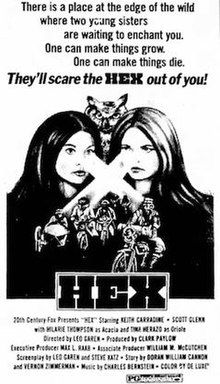

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Leo Garen |

| Written by | Leo Garen Stephen Katz |

| Story by | |

| Produced by | Clark Paylow |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Rosher Jr. |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Charles Bernstein Patrick Williams |

Production company | Max L. Raab Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[4] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $980,000[5] |

Hex is a 1973 American Western supernatural horror film directed by Leo Garen and starring Keith Carradine, Cristina Raines, Hillarie Thompson, Dan Haggerty, Gary Busey, and Scott Glenn. Set in 1919, its plot follows a wayward band of motorcyclists who seek shelter at a rural Nebraska farm inhabited by two Native American sisters. When one of the motorcyclists tries to rape the younger sister, the elder places a curse on them, resulting in their subsequent deaths.

Blending supernatural horror with elements of classic Westerns and the contemporary biker film, Hex was written by Garen and Stephen Katz, based on a story by Vernon Zimmerman and Doran Cannon. The film was shot on location at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota during the fall of 1971, and was distributed by 20th Century Fox. The film was shelved for nearly two years while the studio re-cut it into a more straightforward occult-themed horror film.

The film was released in the fall of 1973, opening at the Atlanta Film Festival, where it won the Golden Jury Award for Best Film. Through September 1973, it screened in some locations, before receiving regional test releases as Hex on 21 November of that year.

Plot

[edit]In 1919, immediately after the First World War, a loosely knit band of motorcyclists back from fighting in Europe is making their way across the United States to seek their fortunes in California. Among them are five men: Whizzer, Golly, Jimbang, Chupo, and Giblets; and one woman, China. In rural Nebraska, the men come upon a small town called Bingo, where they are challenged to a race by a local hot rodder. The outcome of the race is disputed, and the bikers flee into the surrounding countryside.

They seek refuge on a remote farm owned by two sisters, Acacia and Oriole, whose recently deceased father was a Native American shaman. The stern Oriole agrees to let the group spend the night in the barn. In the middle of the night, Giblets attempts to rape Acacia, who fends him off. In retaliation, Oriole casts a hex on him. Shortly after, Giblets is attacked outside by an owl, which digs its claws into his eye sockets, killing him.

The group find Giblets' body the next morning, and Oriole supplies them a wheelbarrow and a shovel, telling them she does not want him buried on her land. They hold a funeral for Giblets under Acacia and Oriole's supervision. The younger, impressionable Acacia becomes enamored of Golly, and the two quickly grow close. Meanwhile, Whizzer teaches Oriole how to drive a motorcycle, during which she crashes it. When Whizzer makes romantic advances toward Oriole, China interjects, revealing that Whizzer is not actually a veteran, and is merely an ex-mechanic from Kansas City who has invented a grandiose story about his life. The two women begin to fight when Oriole insults China. Oriole subsequently places strands of China's hair in the mouth of a toad, before sewing its mouth shut and using it as an effigy.

China goes to a nearby swimming hole to bathe, and falls asleep on the shore, where Oriole has placed the toad. China has a disturbing nightmare in which she is attacked by vermin, and observes an apparition of her own body hanging from a tree. When locals from town arrive in search of the gang, Oriole claims she has not seen them, and directs them away. After the townsmen depart, the gang realize China is missing. After a fruitless search, they return to the farm at nightfall, accusing Oriole and Acacia of hurting her. Jimbang attempts to shoot Oriole to death, but the gun mysteriously misfires and instead kills him. Whizzer wishes to leave, but is unable to find Golly, who has gone off with Acacia. In the barn, Chupo, under Acacia's spell, attacks Whizzer, who pleads for him to stop, but Chupo does not respond; the confrontation ends in Whizzer killing Chupo with a sickle while Oriole watches from the shadows. Oriole enters the barn moments after Chupo's death, and the two have sex.

In the morning, Acacia returns to the house and pleads for Oriole to let China go. Oriole flees back to the swimming hole and stabs the toad, effectively killing China, who has been concealed in the house. Acacia, tired of Oriole using their father's shamanistic magic for evil means, renounces her as her sister. Whizzer and Golly prepare to leave, but find Oriole, donning her father's shaman regalia, causing their motorcycles to combust. She is stopped by Whizzer before she collapses. Later, when Whizzer and Golly are about to depart the farm to California, Golly declares that he wishes to stay with Acacia. Oriole offers to go with Whizzer, and leaves with him on the back of his motorcycle. As they drive away, four fighter jets pass by over them.

Cast

[edit]- Keith Carradine as Archibald "Whizzer" Overton

- Cristina Raines as Oriole (appearing as Tina Herazo)

- Hillarie Thompson as Acacia

- Mike Combs as Golly

- Scott Glenn as Jimbang

- Gary Busey as Gibson "Giblets" Meredith

- Robert Walker as Chupo

- Doria Cook as China

- Dan Haggerty as Brother Billy

- Tom Jones as Elston

- Iggie Wolfington as Bandmaster

Production

[edit]Screenplay

[edit]The original screenplay for Hex was written in 1969 by Vernon Zimmerman and Doran Cannon, conceived as "the biggest piece of schlock they could [write]."[6] The story was completed at the height of the popularity of biker films, and blended plot elements of those films with supernatural horror.[7] Fascinated by the "machines versus mysticism" present in Zimmerman and Cannon's story, Garen purchased the rights to the film and wrote the screenplay with Stephen Katz.[6]

Filming

[edit]Filming of Hex began in September 1971 at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota.[8] The town featured in the film was built on a set for $40,000 in the town of Okaton.[8] Additional photography took place in California.[8] It had a working title of Grassland.[8] According to director Garen, the film's distributor, Twentieth Century Fox, failed to supply him the funds to complete the picture, resulting in him going "totally bankrupt" to complete the shoot.[6] While the majority of the film was shot on location in South Dakota, some sequences were filmed at Fox Studios in Los Angeles.[9] Principal photography was completed in late December 1971.[9]

Actress Hillarie Thompson recalled that, during the South Dakota shoots, the cast and crew nearly "froze to death the entire time. It was very cold and the crew was shoveling snow out of scenes."[10] Thompson also recalled being impressed by her co-stars Busey and Carradine, as well as Scott Glenn, who she said "would go off to a corner for an hour before a scene and go over it and over it by himself."[10]

Post-production

[edit]The film was heavily edited by Twentieth Century Fox executives, who refashioned it by playing up the occult themes in Garen's original cut and removing the comedic undertones.[6] "They cut it for a year and made it a straight occult film," he said.[6] After the studio cut was poorly received during a pre-screening, they allowed Garen to re-cut the film himself.[6] Garen intended the film to be "sort of carnival, snake oil, underground [comic book] entertainment... The only trick I tried to pull off was to keep the audience constantly shifting. When it gets serious, I pull the rug out. It goes from blatant farce to serious to scary to balletic to phantasmagoric."[6] Stills of John Carradine, father of Keith, show the two on the set of the film apparently shooting a scene together, though no footage of John Carradine appears in the final cut of the film.[11]

Release

[edit]Hex played at the Atlanta Film Festival on September 8, 1973,[2] where it won the festival's Golden Jury Award,[12] and screened in Atlanta through the month.[6] In some states, such as Wisconsin, the film was shown under the original title, Grassland.[13] It was given further regional test releases in November 1973,[1] but following lukewarm response from audiences and critics, Twentieth Century Fox decided not to give the film a major theatrical release.[14] In March 1974, it was reported that the film was "gathering dust on the shelf" in Twentieth Century Fox's film archive.[15]

Critical response

[edit]Norman Mailer considered Hex one of the top-ten best films of 1973.[1] According to Phil Hardy's The Encyclopedia of Horror Movies, Hex "crosses elements of the bike film with those of the post-western and the supernatural tale... The film scarcely succeeds in welding its disparate elements together, but still makes a distinctive, atmospheric impression."[16]

Roger Green of the Cedar Rapids Gazette praised the film for its "oft-used but effective horror sequences," adding: "At the start of the flick, the viewer has expectations of a truly humorous adventure with innumerable profound statements of a symbolic nature... After this theory vanishes, one settles back for a hair-straightening, edge-of-the-chair spine-tingler."[17]

Home media

[edit]The film was released on VHS and Betamax in 1991 through Prism Entertainment.[18][19] It was released on DVD in 2006 through Trinity Home Entertainment.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Hex". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Jaynes, Gregory (September 10, 1973). "Film Festival Opener Is Award Material". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. p. 7-D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "This Week at the Theaters". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa. p. 42 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sandra Brennan (2007). "Hex". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2007.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jaynes, Gregory (September 27, 1973). "'Hex' Is Funny and Confusing Film". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. p. 15-D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lisanti 2015, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d "Grass Land Movie Has Youth, Intriguing Plot". The Daily Republic. Mitchell, South Dakota. November 26, 1971. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Grass Land new Fox film". Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario. December 23, 1971. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lisanti 2015, p. 168.

- ^ Weaver & Mank 1999, p. 369.

- ^ "Hex trade advertisement". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. September 20, 1973. p. 4-E – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Grassland trade advertisement". The Capital Times. Madison, Wisconsin. September 25, 1973. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nash & Ross 1985, p. 1216.

- ^ "An awfully awful 'Hex'". The Miami News. Miami, Florida. March 5, 1974. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hardy & Milne 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Green, Roger (November 22, 1973). "'Hex' Is Either Not Enough Or Too Much". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa. p. 12D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Home Video Guide". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. March 29, 1991. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ The Shrieking (VHS). Prism Entertainment. 1991. 2461.

Sources

[edit]- Hardy, Phil; Milne, Tom (1986). The Encyclopedia of Horror Movies. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-0605-5050-9.

- Lisanti, Tom (2015). Drive-in Dream Girls: A Galaxy of B-Movie Starlets of the Sixties. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-49342-5.

- Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1985). The Motion Picture Guide. Vol. 4. Chicago, Illinois: Cinebooks. OCLC 639597412.

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- Weaver, Tom; Mank, Gregory W. (1999). John Carradine: The Films. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-40607-4.

External links

[edit]- 1973 films

- 1973 horror films

- 1973 Western (genre) films

- 1970s supernatural horror films

- American supernatural horror films

- Films about curses

- Films about witchcraft

- Films scored by Charles Bernstein

- Films scored by Patrick Williams (composer)

- Films set in Nebraska

- Films shot in South Dakota

- Films about Native Americans

- Films set in 1919

- Motorcycling films

- Psychedelic films

- American Western (genre) horror films

- 1970s Western (genre) horror films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- 20th Century Fox films

- English-language Western (genre) horror films