Hetch Hetchy

| Hetch Hetchy Valley | |

|---|---|

Top: Taken in the early 1900s before the O'Shaughnessy Dam was constructed, shows the Hetch Hetchy Valley and the Tuolumne River, looking east. Wapama Falls is on the left, Kolana Rock on the right. Bottom: A modern photo, taken from much the same vantage point, shows the submergence of the valley floor under the waters of the reservoir. | |

| Floor elevation | 3,783 ft (1,153 m)[1] |

| Length | 3 mi (4.8 km) |

| Width | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) |

| Area | 1,200 acres (490 ha) |

| Depth | 1,800 ft (550 m) |

| Geology | |

| Type | Glacial |

| Age | 10,000–15,000 years |

| Geography | |

| Location | Yosemite National Park, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 37°56′53″N 119°47′17″W / 37.94806°N 119.78806°W [1] |

| River | Tuolumne River |

Hetch Hetchy is a valley, reservoir, and water system in California in the United States. The glacial Hetch Hetchy Valley lies in the northwestern part of Yosemite National Park and is drained by the Tuolumne River. For thousands of years before the arrival of settlers from the United States in the 1850s, the valley was inhabited by Native Americans who practiced subsistence hunting-gathering.

During the late 19th century, the valley was renowned for its natural beauty – often compared to that of Yosemite Valley – but also targeted for the development of water supply for irrigation and municipal interests. The controversy over damming Hetch Hetchy became mired in the political issues of the day. The law authorizing the dam passed Congress on December 7, 1913. In 1923, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was completed on the Tuolumne River, flooding the entire valley under the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir.[2] The dam and reservoir are the centerpiece of the Hetch Hetchy Project, which in 1934 began to deliver water 167 miles (269 km) west to San Francisco and its client municipalities in the greater San Francisco Bay Area.

Geography

[edit]Before damming, the high granite formations produced a valley with an average depth of 1,800 ft (550 m) and a maximum depth of over 3,000 ft (910 m); the length of the valley was 3 mi (4.8 km) with a width ranging from 1⁄8 to 1⁄2 mile (660 to 2,640 ft; 200 to 800 m). The valley floor consisted of roughly 1,200 acres (490 ha) of meadows fringed by pine forest, through which meandered the Tuolumne River and numerous tributary streams.[3] Kolana Rock, at 5,772 ft (1,759 m), is a massive rock spire on the south side of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Hetch Hetchy Dome, at 6,197 ft (1,889 m), lies directly north of it. The locations of these two formations roughly correspond with those of Cathedral Rocks and El Capitan seen from Tunnel View in Yosemite Valley.[4] A broad, low rocky outcrop situated between Kolana Rock and Hetch Hetchy Dome divided the former meadow in two distinct sections.[5]

The valley is fed by the Tuolumne River, Falls Creek, Tiltill Creek, Rancheria Creek, and numerous smaller streams which collectively drain a watershed of 459 sq mi (1,190 km2). In its natural state, the valley floor was marshy and often flooded in the spring when snow melt in the high Sierra cascaded down the Tuolumne River and backed up behind the narrow gorge which is now spanned by O'Shaughnessy Dam. The entire valley is now flooded under an average 300 ft (91 m) of water behind the dam, although it occasionally reemerges in droughts, as it did in 1955, 1977, and 1991.[6][7]

Upstream from the valley lies the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, while the smaller Poopenaut Valley is directly downstream from O'Shaughnessy Dam. The Hetch Hetchy Road drops into the valley at the dam, but all points east of there are roadless, and accessible only to hikers and equestrians. The O'Shaughnessy Dam is near Yosemite's western boundary, but the long, narrow, fingerlike reservoir stretches eastward for about 8 miles (13 km).[2]

Wapama Falls, at 1,080 ft (330 m), and Tueeulala Falls, at 840 ft (260 m) – both among the tallest waterfalls in North America – are both located in Hetch Hetchy Valley.[8] Rancheria Falls is located farther southeast, on Rancheria Creek.[9] Formerly, a "small but noisy"[10] waterfall and natural pool existed on the Tuolumne River marked the upper entrance to Hetch Hetchy Valley,[11] informally known as Tuolumne Fall (not to be confused with a similarly named waterfall several miles upriver near Tuolumne Meadows). The waterfall on the Tuolumne is now submerged under Hetch Hetchy Reservoir.[citation needed]

Geology

[edit]The Hetch Hetchy Valley began as a V-shaped river canyon cut out by the ancestral Tuolumne River. About one million years ago, the extensive Sherwin glaciation widened, deepened and straightened river valleys along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, including Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite Valley, and Kings Canyon farther to the south.[12] During the last glacial period, the Tioga Glacier[13] formed from extensive icefields in the upper Tuolumne River watershed; between 110,000 and 10,000 years ago Hetch Hetchy Valley was sculpted into its present shape by repeated advance and retreat of the ice, which also removed extensive talus deposits that may have accumulated in the valley since the Sherwin period.[14] At maximum extent, Tioga Glacier may have been 60 mi (97 km) long and up to 4,000 ft (1,200 m) thick, filling Hetch Hetchy Valley to the brim and spilling over the sides, carving out the present rugged plateau country to the north and southwest.[15] When the glacier retreated for the final time, sediment-laden meltwater deposited thick layers of silt, forming the flat alluvial floodplain of the valley floor.[16]

Compared with Yosemite Valley, the walls of Hetch Hetchy are smoother and rounder because it was glaciated to a greater extent. This is because the Tuolumne catchment basin above Hetch Hetchy is almost three times as large as the catchment area of the Merced River above Yosemite, allowing a greater volume of ice to form.[13]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Hetch Hetchy is home to a diverse array of plants and animals. Gray pine, incense-cedar, and California black oak grow in abundance. Many examples of red-barked manzanita can be seen along the Hetch Hetchy Road. Spring and early summer bring wildflowers including lupine, wallflower, monkey flower, and buttercup. Seventeen species of bats inhabit the Hetch Hetchy area, including the largest North American bat, the western mastiff.[8]

Before damming, the valley floor contained abundant stands of black oaks, live oak, Ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and silver fir bordering the meadows, with alder, willow, poplar and dogwood in the riparian zone along the Tuolumne River.[17] The valley's abundant plants provided nourishment for mule deer, black bears and bighorn sheep. Due to large cataracts on the Tuolumne River upstream, Hetch Hetchy Valley may have been in the uppermost range for native rainbow trout in the river.[18]

Due to its abundant wetlands and stream pools, Hetch Hetchy was notorious among early travelers for becoming infested with mosquitoes in the summertime. Said San Francisco resident William Denman in 1918, "The first time I went into the Hetch Hetchy the mosquitoes were intolerable. They would light upon a man's blue shirt and turn it brown, and were voracious as mosquitoes would be."[19]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Hetch Hetchy, California, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1906–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

78 (26) |

85 (29) |

88 (31) |

95 (35) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

93 (34) |

83 (28) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61 (16) |

67 (19) |

73 (23) |

79 (26) |

85 (29) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

85 (29) |

73 (23) |

61 (16) |

98 (37) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 48.9 (9.4) |

52.9 (11.6) |

56.9 (13.8) |

61.7 (16.5) |

69.2 (20.7) |

77.9 (25.5) |

85.1 (29.5) |

84.8 (29.3) |

79.3 (26.3) |

70.5 (21.4) |

54.8 (12.7) |

48.3 (9.1) |

65.9 (18.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 38.8 (3.8) |

41.8 (5.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

49.1 (9.5) |

56.3 (13.5) |

63.8 (17.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

70.5 (21.4) |

64.6 (18.1) |

56.5 (13.6) |

45.3 (7.4) |

38.7 (3.7) |

53.4 (11.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 29.2 (−1.6) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

32.6 (0.3) |

36.7 (2.6) |

42.8 (6.0) |

49.6 (9.8) |

56.2 (13.4) |

56.0 (13.3) |

49.7 (9.8) |

42.0 (5.6) |

33.1 (0.6) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

40.6 (4.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19 (−7) |

21 (−6) |

23 (−5) |

28 (−2) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

49 (9) |

49 (9) |

42 (6) |

33 (1) |

25 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

14 (−10) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

0 (−18) |

10 (−12) |

16 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

36 (2) |

31 (−1) |

31 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

10 (−12) |

1 (−17) |

−4 (−20) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.25 (159) |

5.89 (150) |

5.71 (145) |

3.54 (90) |

2.34 (59) |

0.66 (17) |

0.33 (8.4) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.37 (9.4) |

2.17 (55) |

3.80 (97) |

5.92 (150) |

37.18 (944.9) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.8 (30) |

13.8 (35) |

11.7 (30) |

4.8 (12) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

3.5 (8.9) |

11.0 (28) |

56.8 (144.4) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 8 (20) |

9 (23) |

7 (18) |

2 (5.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (5.1) |

6 (15) |

9 (23) |

| Average precipitation days | 10.5 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 8.1 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 7.0 | 9.9 | 73.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 14.5 |

| Source: WRCC[20] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Indigenous peoples

[edit]People have lived in Hetch Hetchy Valley for over 6,000 years. Native American cultures were prominent before the 1850s when the first settlers from the United States arrived in the Sierra Nevada. During summer, people of the Miwok and Paiute came to Hetch Hetchy from the Central Valley in the west and the Great Basin in the east. The valley provided an escape from the summer heat of the lowlands.[21] They hunted, and gathered seeds and edible plants to furnish themselves winter food, trade items, and materials for art and ceremonial objects. Today, descendants of these people still use milkweed, deergrass, bracken fern, willow, and other plants for a variety of uses including baskets, medicines, and string.[8]

Meadow plants unavailable in the lowlands were particularly valuable resources to these tribes. For thousands of years, Native Americans subjected the valley to controlled bushfires, which prevented forest from taking over the valley meadows.[22] Periodic clearing of the valley provided ample space for the growth of the grasses and shrubs they relied on, as well as additional room for large game animals such as deer to browse. In the 19th century, the first white visitors to the valley did not realize that Hetch Hetchy's extensive meadows were the product of millennia of management by Native Americans; instead they believed "the valley was purely a product of ancient geological forces (or divine intervention) ... this was fundamental to its allure as a destination and subject."[23]

The valley's name may be derived from a Miwok word earlier anglicized as hatchhatchie, which means "edible grasses"[8][24] or "magpie".[25] It is likely that the edible grass was blue dicks.[5] Chief Tenaya of the Yosemite Valley's Ahwaneechee tribe claimed that Hetch Hetchy was Miwok for "Valley of the Two Trees", referring to a pair of yellow pines that once stood at the head of Hetch Hetchy.[22] Miwok names are still used for features, including Tueeulala Fall, Wapama Fall, and Kolana Rock.[8]

While its cousin Yosemite Valley to the south had permanent Miwok settlements,[26] Hetch Hetchy was only seasonally inhabited. This was likely because of Hetch Hetchy's narrow outlet, which in years of heavy snowmelt created a bottleneck in the Tuolumne River and the subsequent flooding of the valley floor.[27]

Exploration and early development

[edit]

In the early 1850s, a mountain man by the name of Nathan Screech[28] became the first non-Native American to enter the valley.[5] Local legend attributes the modern name Hetch Hetchy to Screech's initial arrival in the valley, during which he observed the Native Americans "cooking a variety of grass covered with edible seeds", which they called "hatch hatchy" or "hatchhatchie".[25] Screech reported that the valley was bitterly disputed between the "Pah Utah Indians" (Paiute) and "Big Creek Indians" (Miwok), and witnessed several fights in which the Paiute appeared to be the dominant tribe.[29][30] About 1853, his brother, Joseph Screech (credited in some accounts for the original discovery of the valley)[28] blazed the first trail from Big Oak Flat, a mining camp near present-day Lake Don Pedro,[31] for 38 mi (61 km) northeast to Hetch Hetchy Valley.[32]

During this time, the upper Tuolumne River, including Hetch Hetchy Valley, was visited by prospectors attracted by the California Gold Rush. Miners did not stay in the area for long, however, as richer deposits occurred further south along the Merced River and in the Big Oak Flat area.[31] After the valley's native inhabitants were driven out by the newcomers, it was used by ranchers, many of whom were former miners, to graze livestock. Animals were principally driven along Joseph Screech's trail from Big Oak Flat to Hetch Hetchy.[32] Its meadows provided abundant feed for "thousands of head of sheep and cattle that entered lean and lank in the spring, but left rolling fat and hardly able to negotiate the precipitous and difficult defiles out of the mountains in the fall."[33]

In 1867, Charles F. Hoffman of the California Geological Survey conducted the first survey of the valley. Hoffman observed a meadow "well timbered and affording good grazing", and noted the valley had a milder climate than Yosemite Valley, hence the abundance of ponderosa pine and gray pine.[5] The valley was slowly becoming known for its natural beauty, but it was never a popular tourist destination because of extremely poor access and the location of the famous Yosemite Valley just 20 miles (32 km) to the south. Those who did visit it were enchanted by its scenery, but encountered difficulties with the primitive conditions and, in summertime, swarms of mosquitoes.[22][34] Albert Bierstadt, Charles Dorman Robinson and William Keith were known for their landscapes that drew tourists to the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Bierstadt described the valley as "smaller than the more famous valley ... but it presents many of the same features in his scenery and is quite as beautiful."[35]

When Yosemite Valley became part of a state park in 1864, Hetch Hetchy received no such designation. As the grazing of livestock damaged native plants in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, mountaineer and naturalist John Muir pressed for the protection of both valleys under a single national park.[36] Muir, who himself had briefly worked as a shepherd in Hetch Hetchy, was known for calling sheep "hoofed locusts" because of their environmental impact.[37] Muir's friend Robert Underwood Johnson of the politically influential Century Magazine and several other prominent figures were inspired by Muir's work and helped to get Yosemite National Park established by October 1, 1890.[38][39] However, ranchers who had previously owned land in the new park continued their use of Hetch Hetchy Valley – a "sheep-grazing free-for-all [that] threatened to denude the High Sierra meadows"[38] – before disputes over state and private properties in respect to national park boundaries were finally settled in the early 1900s.[40]

Interest in using the valley as a water source or reservoir dates back as far as the 1850s, when the Tuolumne Valley Water Company proposed developing water storage there for irrigation.[41] By the 1880s, San Francisco was looking to Hetch Hetchy water as a fix for its outdated and unreliable water system.[41] The city would repeatedly try to acquire water rights to Hetch Hetchy, including in 1901, 1903 and 1905, but was continually rebuffed because of conflicts with irrigation districts that had senior water rights on the Tuolumne River, and because of the valley's national park status.[42]

Damming

[edit]In 1906, after a major earthquake and subsequent fire that devastated San Francisco, the inadequacy of the city's water system was made tragically clear. San Francisco applied to the United States Department of the Interior to gain water rights to Hetch Hetchy, and in 1908 President Theodore Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior, James R. Garfield, granted San Francisco the rights to development of the Tuolumne River.[43] This provoked a seven-year environmental struggle with the environmental group Sierra Club, led by John Muir. Muir observed:[3]

Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.

Proponents of the dam replied that out of multiple sites considered by San Francisco, Hetch Hetchy had the "perfect architecture for a reservoir",[44] with pristine water, lack of development or private property, a steep-sided and flat-floored profile that would maximize the amount of water stored, and a narrow outlet ideal for placement of a dam.[43] They claimed the valley was not unique and would be even more beautiful with a lake. Muir predicted that this lake would create an unsightly "bathtub ring" around its perimeter, caused by the water's destruction of lichen growth on the canyon walls,[45] which would inevitably be visible at low lake levels.

Since the valley was within Yosemite National Park, an act of Congress was needed to authorize the project. The U.S. Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed the Raker Act in 1913, which permitted the flooding of the valley under the conditions that power and water derived from the river could only be used for public interests. Ultimately, San Francisco sold hydropower from the dam to the Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), which led to decades of legal wrangling and controversy over terms in the Raker Act.[46]

The controversy over Hetch Hetchy was in the context of other political scandals and controversies, especially prevalent in the Taft administration. The Great Alaskan Land Fraud and the Pinchot-Ballinger Controversy caused both Richard A. Ballinger and Gifford Pinchot to resign and be fired respectively. The openings in the Taft administration led to the eventual success of the Raker Act.[47]

Work on the Hetch Hetchy Project began in 1914. The 68 mi (109 km) Hetch Hetchy Railroad was constructed to link the Sierra Railway with Hetch Hetchy Valley, allowing for direct rail shipment of construction materials from San Francisco to the dam site. Construction of O'Shaughnessy Dam began in 1919 and was finished in 1923, with the reservoir first filling in May of that year. The dam was then 227 feet (69 m) high; its present height of 312 feet (95 m) was achieved only later, in 1938.[48] On October 28, 1934 – twenty years after the beginning of construction on the Hetch Hetchy project – a crowd of 20,000 San Franciscans gathered to celebrate the arrival of the first Hetch Hetchy water in the city.[49]

The Early Intake (Lower Cherry) Powerhouse began commercial operation five years before the O'Shaughnessy Dam was completed. The first Moccasin Powerhouse in Moccasin, California began commercial operation in 1925 followed by the Holm Powerhouse in 1960 (the same month the Early Intake Powerhouse was taken out of service). In 1967 the Robert C. Kirkwood Powerhouse started commercial operation followed by a New Moccasin Powerhouse in 1969 when the Old Moccasin Powerhouse was taken out of service. Finally, in 1988, a third generator was added to the Kirkwood Powerhouse.[50]

-

The narrow defile at the lower end of Hetch Hetchy Valley where San Francisco planned to dam the Tuolumne River, seen in 1914 before construction began

-

The same area seen today, with O'Shaughnessy Dam and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir

-

Tuolumne River below O'Shaughnessy Dam

Hetch Hetchy Project

[edit]Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°56′51″N 119°47′13″W / 37.9475°N 119.7869°W |

| Begins | Tuolumne River 37°51′09″N 119°59′30″W / 37.852425°N 119.991572°W |

| Ends | Crystal Springs Reservoir 37°29′01″N 122°18′59″W / 37.483508°N 122.316306°W |

| Maintained by | San Francisco Public Utilities Commission |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 167 mi (269 km) |

| Capacity | 366 cu ft/s (10.4 m3/s) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1914 |

| Opened | 24 October 1934 |

| Location | |

| |

| References | |

| U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hetch Hetchy. Note that map above only shows Bay Area portion of aqueduct. | |

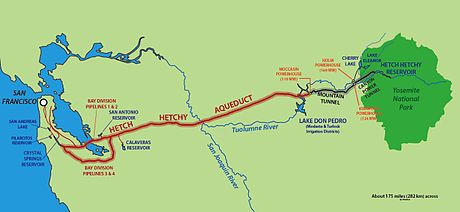

Hetch Hetchy Valley serves as the primary water source for the City and County of San Francisco and several surrounding municipalities in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. The dam and reservoir, combined with a series of aqueducts, tunnels, and hydroelectric plants as well as eight other storage dams, comprise a system known as the Hetch Hetchy Project, which provides 80% of the water supply for 2.6 million people.[51] The project is operated by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. The city must pay a lease of $30,000 per year for the use of Hetch Hetchy, which sits on federal land.[52][53] The aqueduct delivers an average of 265,000 acre⋅ft (327,000,000 m3) of water each year, or 31,900,000 cu ft (900,000 m3) per day, to residents of San Francisco and San Mateo, Santa Clara and Alameda Counties.[54]

As completed, O'Shaughnessy Dam is 910 feet (280 m) long, spanning the valley at its narrow outlet.[2] The dam contains 675,000 cu yd (516,000 m3) of concrete. The Hetch Hetchy Reservoir created by the dam has a capacity of 360,400 acre⋅ft (0.4445 km3), with a maximum area of 1,972 acres (798 ha) and a maximum depth of 306 feet (93 m).[2] From Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, the water flows through the Canyon and Mountain Tunnels to Kirkwood and Moccasin Powerhouses, which have capacities of 124 and 110 megawatts, respectively.[55] An additional hydroelectric system comprising Cherry Lake, Lake Eleanor and the Holm Powerhouse is also part of the Hetch Hetchy Project, adding another 169 megawatts of generating capacity.[55] The entire system produces about 1.7 billion kilowatt hours per year, enough to meet 20% of San Francisco's electricity needs.[55][56]

After passing through the powerhouses, Hetch Hetchy water flows into the 167 mi (269 km) Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct which travels across the Central Valley. Just before reaching the Bay Area, it passes through the Irvington tunnel near the city of Fremont, and the aqueduct splits into four pipelines at 37°32′53″N 121°55′55″W / 37.548104°N 121.932041°W. These are called Bay Division Pipelines (BDPL) 1, 2, 3, and 4, with nominal pipeline diameters of 60, 66, 78, and 96 inches (1.5, 1.7, 2.0 and 2.4 m, respectively).[57] All four pipelines cross the Hayward fault. Pipelines 1 and 2 cross the San Francisco Bay to the south of the Dumbarton Bridge, while pipelines 3 and 4 run to the south of the bay. In the Bay Area, Hetch Hetchy water is stored in local facilities including Calaveras Reservoir, Crystal Springs Reservoir, and San Antonio Reservoir.[58] Pipelines 3 and 4 end at the Pulgas Water Temple, a small park that contains classical architectural elements which celebrate the water delivery.[59]

Water from Hetch Hetchy is some of the cleanest municipal water in the United States; San Francisco is one of six U.S. cities not required by law to filter its tap water, although the water is disinfected by ozonation and, since 2011, exposure to UV.[60] The water quality is high because of the unique geology of the upper Tuolumne River drainage basin, which consists mostly of bare granite; as a result, the rivers feeding Hetch Hetchy Reservoir have extremely low loads of sediments and nutrients. The watershed is also strictly protected, so swimming and boating are prohibited at the reservoir (although fishing is permitted at the reservoir and in the rivers which feed it),[61] a measure which is considered unusual for US lakes outside the region.[62] In 2018, the Department of the Interior of the Trump administration began to consider a proposal to allow limited boating on the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir for the first time, supported by the advocacy group Restore Hetch Hetchy which argued that "San Francisco received [Hetch Hetchy's] benefits long ago, but the American people have not."[62][63]

Proposed restoration

[edit]Arguments for

[edit]The battle over Hetch Hetchy Valley continues today[when?] between those who wish to retain the dam and reservoir, and those who wish to drain the reservoir and return Hetch Hetchy Valley to its former state. Those in favor of dam removal have pointed out that many actions by San Francisco since 1913 have been in violation of the Raker Act, which explicitly stated that power and water from Hetch Hetchy could not be sold to private interests. Hydroelectric power generated from the Hetch Hetchy project is largely sold to Bay Area customers through a private power company, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E). San Francisco was able to accomplish this in 1925 by claiming it had run out of funds to extend the Hetch Hetchy transmission line all the way to the city. The terminus of the incomplete line was "conveniently located next to a PG&E substation", which connected to PG&E's private line which in turn bridged the gap to San Francisco.[64] The city justified this as a temporary measure, but no attempt to follow through with completing the municipal grid was ever made.[65] Peter Byrne of SF Weekly has stated that "the plain language of the Raker Act itself and experts who are familiar with the act (and have no stake in city politics) all agree: The city of San Francisco is not in violation of the Raker Act."[66] Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior in the late 1930s, said there was a violation of the Raker Act, but he and the city reached an agreement in 1945.[67] In 2015, Restore Hetch Hetchy filed a complaint arguing that the construction of the dam had violated a provision in the constitution of California about water use, but the lawsuit was rejected by an appeals court and later the California State Supreme Court.[68]

Preservation groups including the Sierra Club and Restore Hetch Hetchy state that draining Hetch Hetchy would open the valley back up to recreation, a right that should be provided to the American people because the reservoir is within the legal boundaries of a national park. They acknowledge that a concerted effort would have to be made to control the introduction of wildlife and tourism back into the valley in order to prevent destabilization of the ecosystem,[69] and that it might be decades or even centuries before the valley could be returned to natural conditions.[70]

In 1987, the idea of razing the O'Shaughnessy Dam gained an adherent in Don Hodel, Secretary of the Department of the Interior under President Ronald Reagan.[71] Hodel called for a study of the effect of tearing down the dam. The National Park Service concluded that two years after draining the valley, grasses would cover most of its floor and within 10 years, clumps of cone-bearing trees and some oaks would take root. Within 50 years, vegetative cover would be complete except for exposed rocky areas. In this unmanaged scenario, where nature is left to take hold in the valley, eventually a forest would grow, rather than the meadow being restored. However, the same NPS study also finds that with intensive management, an outcome in which "the entire valley would appear much as it did before construction of the reservoir" is feasible.[72]

The dam would not have to be completely removed; rather, it would only be necessary to cut a hole through the base in order to drain the water and restore natural flows of the Tuolumne River. Most of the dam would remain in place, both to avoid the enormous costs of demolition and removal, and to serve as a monument for the workers who built it.[73] The water storage provided at Hetch Hetchy could be transferred into Lake Don Pedro lower on the Tuolumne River by raising the New Don Pedro Dam 30 ft (9.1 m). Water could be diverted into the Kirkwood and Moccasin Powerhouses using lower-impact diversion dams, providing power generation on a seasonal basis, and the increased height, and thus hydraulic head, at Don Pedro would also increase power generation there.[74] Furthermore, the removal of O'Shaughnessy Dam would not require costly sediment control measures, as would be typical on most dam removal projects, because of the high quality of the Tuolumne River water – in the first 90 years since its construction, only around 2 in (5.1 cm) of sediment had been deposited in Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, much less than most other dams.[75] A 2019 study commissioned by Restore Hetch Hetchy argued that draining the reservoir and equipping the valley with a tourism infrastructure comparable to that of Yosemite Valley (which receives around 100 times as many visitors annually as Hetch Hetchy's 44,000) could result in a "recreational value" of up to $178 million per year, or possibly an overall economic value of up to $100 billion.[68]

Arguments against

[edit]

Those in opposition of dam removal state that demolishing O'Shaughnessy Dam would take away a valuable source of clean, renewable hydroelectric power in the Kirkwood and Moccasin powerhouses; even if measures such as seasonal water diversion into the powerhouses were employed, it would only make up for a fraction of the original power production.[76] The remaining deficit would likely have to be replaced by polluting fossil fuel generation.[51] The removal of the dam would be extremely costly, at least $3–10 billion,[77] and the transport of the demolished material away from the dam site along the narrow, winding Hetch Hetchy Road would be a logistical nightmare with possible environmental impacts. Most importantly, San Francisco would lose its source of high-quality mountain water, and would have to depend on lower-quality water from other reservoirs – which would require costly filtration and re-engineering of the aqueduct system – to meet its needs.[78][79]

The economic wisdom of removing the dam has been frequently questioned.[80] Some observers, such as Carl Pope (director of the Sierra Club), stated that Hodel had political motives[81] in proposing the study. The imputed motive was to divide the environmental movement: to see residents of the strongly Democratic city of San Francisco coming out against an environmental issue. Dianne Feinstein, the mayor of San Francisco at the time, said in a Los Angeles Times story in 1987: "All this is for an expanded campground? ... It's dumb, dumb, dumb."[82] Hodel, now retired, remains [when?] a strong proponent of restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley and Senator Feinstein remained [when?] strongly against restoration.[citation needed] The George W. Bush administration proposed allocating $7 million to studying the removal of the dam in the 2007 National Park Service budget.[83] Dianne Feinstein opposed this allocation, saying, "I will do all I can to make sure it isn't included in the final bill. We're not going to remove this dam, and the funding is unnecessary."[84]

Opponents of dam removal have pointed out that the flooding of the Hetch Hetchy Valley has also deterred the crowds that overrun other areas of Yosemite National Park. Indeed, Hetch Hetchy today[when?] remains the least visited developed area of the park.[85] Karin Klein has described Yosemite Valley as "so crammed ... that it looks more like a ripstop ghetto than the site of a nature experience."[86] However, she does support breaching the dam once it has reached the end of its lifespan, and not replacing it.[86] In November 2012, San Francisco voters soundly rejected Proposition F,[87] which would have required the city to conduct an $8 million study on how the flooded valley could be drained and restored to its former state. The proposed study would also have been required to identify potential replacements for the water storage capacity and hydroelectric power production.[88][89]

See also

[edit]- Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne

- Hetch Hetchy Railroad

- Lake Vernon trail

- List of dams and reservoirs in California

- List of power stations in California

- List of the tallest dams in the United States

- List of lakes in California

- List of largest reservoirs of California

- The National Parks: America's Best Idea

- Gifford Pinchot

- San Francisco Public Utilities Commission

- San Francisco Water Department

- Timeline of environmental events

- Tuolumne River

- Yosemite National Park

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Hetch Hetchy Valley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1990-08-01. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ a b c d "Hetch Hetchy". San Francisco Water Power Sewer. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ a b Muir, John (1912). "Hetch Hetchy Valley". The Yosemite. New York: The Century Co.

- ^ "Nature's Garden". Restore Hetch Hetchy. Archived from the original on 2013-07-19. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ a b c d Hoffmann, Charles F. (1868). "Notes on Hetch-Hetchy Valley". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 1. 3 (5). San Francisco: CAS: 368–370.

- ^ "Alternatives for Restoration of Hetch Hetchy Valley Following Removal of the Dam and Reservoir" (PDF). Sierra Club. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Hetch Hetchy Reclaimed: Drain it, then what?". The Pulitzer Prizes.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from Hetch Hetchy Valley (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

This article incorporates public domain material from Hetch Hetchy Valley (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ "Rancheria Falls". Yosemite National Park / Hetch Hetchy, California, USA. World of Waterfalls.

- ^ Righter 2005, p. 15.

- ^ "Fall in the Main Tuolumne River at the Head of Hetch Hetchy Valley". Requiem for Hetch Hetchy Valley. Sierra Club.

- ^ Huber 2007, p. 80–83.

- ^ a b Huber, N. King. Geologic Story of Yosemite Valley. USGS. Bulletin 1595. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Huber 2007, p. 84.

- ^ Matthes 1930, pp. 87–90.

- ^ Wohlforth 2004, p. 419.

- ^ "Restoring Hetch Hetchy". Patagonia Environmentalism Essay.

- ^ "Fly Fishing Poopenaut Valley Tuolumne River". The Ecological Angler.

- ^ Committee on the Public Lands (1918). Hetch Hetchy dam site: hearing before the Committee on the Public Lands, House of representatives. Sixty-third Congress, first session, on H.R. 6281, a bill granting to the city and county of San Francisco certain rights of way in, over, and through certain public lands, the Yosemite National Park, and Stanislaus National Forest, and certain lands in the Yosemite National Park, the Stanislaus National Forest, and the public lands in the state of California, and for other purposes. [June 25, 1913]. USGPO. p. 243. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "HETCH HETCHY, CALIFORNIA - Climate Summary".

- ^ Jones 2010, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Jones 2010, p. 75.

- ^ Bibby 2006, p. 92–94.

- ^ Farquhar, Francis P. (1926). "Place Names of the High Sierra". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ a b Simpson 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Simpson 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Simpson 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b "Screech Brothers Find Hetch Hetchy Valley". Yosemite Gazette. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Early History". Hetch Hetchy: Preservation or Public Utility. In Time and Place.

- ^ Whitney 1874, p. 158.

- ^ a b "Big Oak Flat (No. 406 California Historical Landmark)". Sierra Nevada Geotourism MapGuide. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ a b Whitney 1874, p. 157.

- ^ Righter 2005, p. 17.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers (1913). Hetch Hetchy Valley: report of Advisory Board of Army Engineers to the Secretary of the Interior on investigations relative to sources of water supply for San Francisco and Bay communities. United States Government Printing Office. p. 31.

- ^ Righter 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Righter 2005, pp. 22–23.

- ^ "John Muir". Yosemite National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- ^ a b Righter 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Perrottet, Tony (July 2008). "John Muir's Yosemite: The father of the conservation movement found his calling on a visit to the California wilderness". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ Righter 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b "Timeline of the Ongoing Battle Over Hetch Hetchy". Sierra Club. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ United States Department of the Interior. "Proceedings Before The Secretary Of The Interior In Re Use Of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir Site, In The Yosemite National Park, By The City Of San Francisco, May 11, 1908". United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b Hanson, Jason L. "The Hetch Hetchy Letters: If a Group of Intellectuals Argues in a Forest, and then that Forest is Submerged Under Water, Does Their Argument Matter?" (PDF). Center of the American West. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-02. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ Davies, Leslie T. (May 2006). "San Francisco-Hetch Hetchy Valley Connection" (PDF). Humboldt State University. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (2012-09-30). "Hetch Hetchy controversy: Could Yosemite's 'second valley' be restored?". San Jose Mercury News.

- ^ "The Hetch Hetchy Story, Part II: PG&E and the Raker Act". FoundSF.

- ^ Mansfield, Gabriel (2018). "The Forbidden Water: San Francisco and Hetch Hetchy Valley" (PDF). Historia. 27: 24–31.

- ^ "Hetch Hetchy Water and Power System". Tuolumne County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Buchanan, Paul D. (April 2, 2001). "Idyllic Pulgas Water Temple still offers comfort for weary wanderers". San Mateo Daily Journal.

- ^ "Chronology of San Francisco's Water Development". Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions About Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and the Regional Water & Power System". San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Archived from the original on 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Upton, John (6 January 2012). "Water From Yosemite Is Still Cheap, for Now". The New York Times. p. 21A. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Righter 2005, p. 241.

- ^ "The Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct". Aquafornia. 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ a b c "Tuolumne River System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-02. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Power Plants of California". California Energy Almanac. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ Eidinger, J. M. (2001). "Seismic Retrofit of the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct at the Hayward Fault". Pipelines 2001. pp. 1–0. doi:10.1061/40574(2001)75. ISBN 978-0-7844-0574-1.

- ^ "Serving 2.6 million residential, commercial and industrial customers". San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ "Pulgas Water Temple". San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. 26 February 2024.

- ^ Worth, Katie (2011-07-18). "Hetch Hetchy water goes through ultraviolet rinse". San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ "Hetch Hetchy Valley" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service. March 2007. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ a b Stienstra, By Tom (2019-09-28). "A historic bid for limited boating at Hetch Hetchy Reservoir". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (2019-10-23). "Trump team reassigns Yosemite National Park superintendent; timing raises questions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Browne, Brian. "Western Water Wars: Efforts to Take Over San Francisco's Hetch Hetchy Systems" (PDF). Reason Foundation. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Redmond, Tim (2004-05-26). "Hetch Hetchy Power Debacle: Continuing Yosemite Threat". Trails. Clovis Free Press. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Byrne, Peter (2001-04-04). "Delusions of Power". San Francisco Weekly.

- ^ Righter 2005, p. 185.

- ^ a b Thomas, Gregory (2019-08-01). "Could Hetch Hetchy Valley be worth $100 billion?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- ^ De Carion, Denis. "Three Square Miles of Open Space: Is It Enough?" (PDF). University of California Davis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ "Alternatives for Restoration of Hetch Hetchy Valley Following Removal of the Dam and Reservoir" (PDF). Sierra Club. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ Philp, Tom (2004-08-19). "Hetch Hetchy reclaimed: The dam downstream". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ^ Riegelhuth, Richard; Botti, S.; Keay, J. "Alternatives for restoration of Hetch Hetchy Valley following removal of the dam and reservoir page 15" (PDF).

- ^ "What Lies Beneath?" (PDF). Backcountry Pictures. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ Nash, J. Madeline (2005-07-11). "Is This Worth a Dam?". Time. Archived from the original on July 14, 2005.

- ^ Biba, Erin (2012-12-11). "What Happens When You Remove a Dam". Popular Mechanics.

The valley would be covered in about two inches of sediment, which is unusual to Hetch Hetchy; many dams collect large amounts of sediment, however the Tuolumne riverbed is mostly granite and erodes slowly.

- ^ "Chapter 9: Impact of restoration on hydropower production and revenues" (PDF). Environmental Defense Fund. Retrieved 2013-05-25.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hetch Hetchy Restoration Study" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. 2006. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ "Worth a Dam? Hetch Hetchy in Yosemite". Earth Island Journal. 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (2012-09-09). "Putting Bay Area's Water Sources to a Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ Bowe, Rebecca (2011-08-09). "Ecological rewind: Environmentalists want to tear down O'Shaughnessy Dam and restore the Hetch Hetchy Valley, but does their plan hold water?". San Francisco Bay Guardian.

- ^ Pope, Carl (November–December 1987). "Undamming Hetch Hetchy". Sierra. Sierra Club: 34–38.

- ^ Morain, Dan; Houston, Paul (1987-08-07). "Hodel Would Tear Down Dam in Hetch Hetchy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ Glennon 2009, p. 121.

- ^ Doyle, Michael (2007-02-08). "Hetch Hetchy debate reborn". Sacramento Bee.

- ^ "What will a restored valley look like?". Restore Hetch Hetchy. Archived from the original on 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ^ a b Klein, Karin (2012-08-15). "On Hetch Hetchy, John Muir was wrong: California's revered naturalist wrote a poetic diatribe against the drowning of the great valley. But the reservoir has spared it some of the indignities of Yosemite Valley". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035.

- ^ "San Francisco Department of Elections, November 2012 Results". Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Wildermuth, John (2012-11-10). "Hetch Hetchy fight not over, activists say". San Francisco Examiner.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (2012-11-12). "San Francisco vote to study draining Hetch Hetchy Reservoir is defeated". Mercury News. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

General and cited references

[edit]- Bibby, Brian (2006). Scott, Amy (ed.). Yosemite: Art of an American Icon (section). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24922-4.

- Glennon, Robert Jerome (2009). Unquenchable: America's Water Crisis and What to Do About It. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726-639-0.

- Huber, Norman King (2007). Geological Ramblings in Yosemite. Heyday. ISBN 978-1-59714-072-0.

- Jones, Ray (2010). It Happened in Yosemite National Park: Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-6231-6.

- Matthes, François (1930). Geologic history of the Yosemite valley. United States Government Printing Office.

- Righter, Robert W. (2005). The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195149470.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-803410-0.

- Simpson, John W. (2005). Dam!: Water, Power, Politics, and Preservation in Hetch Hetchy and Yosemite National Park. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-375-42231-5.

- Whitney, Josiah Dwight (1874). The Yosemite guide-book: a description of the Yosemite Valley and the adjacent region of the Sierra Nevada, and of the big trees of California. University Press; printed by Welch, Bigelow, and Co.

- Wohlforth, Charles P. (2004). Frommer's Family Vacations in the National Parks. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-7645-7075-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Aqua Blog Maven (19 August 2008). "The Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct". Aquafornia. Archived from the original on 2013-01-10. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- Bay Area Economic Forum (October 2002). "Hetch Hetchy Water and the Bay Area Economy" (PDF). Bay Area Council and the Association of Bay Area Governments: 5. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Dziegielewski, Benedykt; Garbharran, Hari P.; Langowski, John F. Jr (1997). Lessons Learned from the California Drought (1987–1992) (illustrated ed.). Diane Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 0-7881-4163-5.

- Null, Sarah (December 2003). "Thesis: Water Supply Implications of Removing O'Shaughnessy Dam" (PDF). University of California, Davis. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "San Francisco Water Sources". San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- Flagg, Jeffrey B. (2011). "National Parks and Water". CQ Press.

- De Benedetti, Chris (2015). "New Irvington Tunnel latest in Hetch Hetchy water system improvements". Mercury News. Retrieved Dec 31, 2015.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hetch Hetchy

- O'Shaughnessy Dam at Structurae

- Current Conditions, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, California Department of Water Resources

- San Francisco Public Utilities Commission: Hetch Hetchy Water and Power

- United States Geological Survey

- California Resources Agency Hetch Hetchy Restoration Study

- Bay Area Water Supply and Conservation Agency on Hetch Hetchy dam

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-366, "Bay Crossing Reach of the Bay Division Pipelines Nos. 1 and 2, Fremont, Alameda County, CA", 50 photos, 81 data pages, 4 photo caption pages