Herman George Scheffauer

Herman G. Scheffauer | |

|---|---|

Hermann Scheffauer | |

| Born | Herman George Scheffauer February 3, 1876 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | 7 October 1927 (aged 51) Berlin, Germany |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Spouse | Ethel Talbot Scheffauer |

Herman George Scheffauer (February 3, 1876 – October 7, 1927) was a German-American poet, architect, writer, dramatist, journalist, and translator.

San Francisco childhood

[edit]Little is known about Scheffauer's youth, education and his early adult years in America, or, about his parents and siblings. His father was Johann Georg Scheffauer, a cabinet maker ("Tischler"), probably born in 1842 in the village of Unterkochen, Württemberg, who, according to Hamburg passenger lists, had first immigrated to America in 1868, returning again to Germany where he married Maria Theresa Eisele in Augsburg, and who then came back with him to America in 1872.[1] His brother was the civil engineer, Frederick Carl Scheffauer, born in 1878[2] and he had another younger brother, Walter Alois Scheffauer (1882–1975). The family was related to the German painter and sculptor Philipp Jacob Scheffauer (1756–1808)[3] who it was said was his great-grandfather,[4] who went to the same school as the poet Friedrich Schiller and in Stuttgart moved in a circle of German poets such as Friedrich Haug, Ludwig Ferdinand Huber and Friedrich Hölderlin.

Educated in public and private schools, he attended a Roman Catholic Sunday school in San Francisco, where services were conducted in German. He later wrote about the role of the nuns there and a certain Father Gerhard, instilling into the youth of this school terrifying and hellish religious imagery.[5] His parents were not orthodox, in fact he spoke of being shocked by his father's religious indifference and scepticism. He discovered that he was a poet from about the age of ten, on a school outing, where the pupils ascended Mount Olympus in the Ashbury Heights neighbourhood of San Francisco.[6] He impressed his school friends with his ability to recount the ascent, as he put it:

Suddenly I burst forth into a jog-trot doggerel. I chanted the heroic deeds of the day – the ascent of the peak, the routing of a belligerent bull, the piratical manoeuvres on a pond. The delivery of this improvised epic was volcanic. My companions regarded me with awe and suspicion. Thus, primitively and barbarically, I began. The climate had had its will of me – that marvellous 'Greek' climate of California which works like champagne upon the temperament. I was fated to become one of the native sons of song.[7]

From then on he only wanted to write poetry but his parents insisted that he pursue a proper job. He began his career as an amateur printer, printing a broadsheet called The Owl while he was still at school writing satires on his schoolmates and teachers and "mournful valedictory odes". He went through a youthful period, through which he thought all young poets with an imaginative cast of mind must inevitably pass, namely a combination of what he termed "idealistic fanaticism and Byronic romanticism".[8] He studied art, painting and architecture at the Arts School of the University of California (The Mark Hopkins Institute).[9] He later worked as an architect, a teacher of draughting and a water colourist.[10]

Early intellectual influences

[edit]He was aware that "Ingersoll was in the air",[11] a reference to the ideas of Robert G. Ingersoll the American freethinker and agnostic, and Scheffauer admitted that at first he looked upon Ingersoll and his followers as "enemies", and intellectually cowering, as it were, he read The Night Thoughts (1742) of the deeply religious English poet Edward Young to reaffirm his faith.[12]

However, he soon departed from his religiosity and became aware of the heated discussions about the "missing link" in the writings of John Augustine Zahm, the priest and professor of physics at the University of Notre Dame (South Bend, Indiana). He said that the following authors came to his aid in California bringing him "light and fire",[13] namely works by Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, Arthur Schopenhauer, Herbert Spencer, Ludwig Feuerbach and Ludwig Büchner.[13] Probably the greatest influence on his thinking, in the sense of a clearer scientific Weltanschauung, was a chance encounter with a work of the German zoologist, biologist and philosopher, and popularizer of Darwin's evolutionary theory, Ernst Haeckel.[14] He came across the massively popular book Die Welträtsel (The world riddles or enigmas) in the F.W. Barkhouse bookshop, 213 Kearney Street, San Francisco, which was translated by Joseph McCabe as The Riddle of the Universe at the close of the nineteenth century (1901).[15] He bought a copy and read half of it the same evening and the rest in his architect bureau the following day. He would later describe himself as a monist poet, and claimed that together with his close friend George Sterling they represented "a new school of poetry" in California, developing "a poetry that sought to unify poetry with science".[16]

Protégé of Ambrose Bierce

[edit]Scheffauer later gave up his architectural day job and wrote poetry and short stories. He was encouraged by his friend and mentor Ambrose Bierce the journalist, short story writer and veteran of the Civil War. How they actually first met is uncertain. It has been claimed,[17] that Bierce had first noticed a poem of his entitled The Fair Grounds that he had entered in a literary competition in 1893, organised by the San Francisco newspaper The Call.

Scheffauer who was only 17 years of age had used the pseudonym Jonathan Stone, and his poem was favorably compared to the American romantic poet William Cullen Bryant.[18] Bierce, who was 36 years older, became an alternative father figure for him and as a mentor criticized, encouraged and nurtured his poetic sensibility. Bierce published a number of his poems in his own "Prattle" columns. In 1899 Bierce was responsible for the so-called "Poe-Scheffauer affair". One of Scheffauer's poems, "The Sea of Serenity" (1893) was published in the San Francisco Examiner on March 12, 1899, albeit not under his own name but heralded as "an unpublished poem" of Edgar Allan Poe".[19]

This carefully planned "Poe hoax" passed without creating too much attention. However, it elicited some of the greatest praise from Bierce for the young poet:

I am very far from saying that I think the poem mentioned was written by Poe ... As to internal evidence— evidence inhering in the poem itself— that is strongly in favor of Poe's authorship. If not written by him it was written by his peer in that kind of writing— by one who has so thoroughly mastered the method that there is nowhere a slip or fault. The writer, if not Poe, has caught the trick of Poe's method utterly, in both form and manner, the trick of his thought, the trick of his feeling and the trick of that intangible something which eludes nomenclature, description and analysis ... He need not fear any dimming of his glory, for distinctly greater than the feat of hearing "a voice from the grave of Edgar Allan Poe" is the feat of discovering a ventriloquist with that kind of voice.[19]: 11

Another early poem of his, also written in the spirit of Poe, entitled The Isle of the Dead (1894) was later published under his own name in the Californian Overland Monthly. The poem was published together with the image of the painting 'Die Toteninsel' by the Swiss-German artist Arnold Böcklin. Scheffauer translated Goethe, read Walt Whitman and Rudyard Kipling avidly, adored W. B. Yeats and discussed with Bierce varied themes such as the poems of the Irish poet Thomas Moore who he declared to be "the greatest of the lover poets"[20] and the technical nature of Algernon Swinburne's alliteration. The full correspondence with Bierce has not yet been published but the encouragement and belief that he showed in him as a young American poet is palpable: "I so like the spirit of your letter of July 7! It gives me assurance of your future. You are to do great work, believe me. I shall not see it all, but that does not greatly matter, having the assurance of it."[21] In his 'Prattle' column in 1897 he had already called the young poet "...my gifted young friend "Jonathan Stone" – of whom I have already filed a prediction that the world will one day be turning an attentive ear his way."[22]

The publication of his first collection of poems Of Both Worlds (1903) was dedicated to Bierce. It has a number of English translations from Goethe, including Der König in Thule from Faust. At about the same time he also began to read Nietzsche enthusiastically. Bierce was pleased with the effect this was having on him: "I can bless your new guide for at least one service to you—for overturning one of your idols: the horrible God of the Hebrew mythology, horrible even in his softened character, as we now have him."[23] Bierce's ironic 'blessing' of Nietzsche reveals the extent and legacy of Scheffauer's Catholic upbringing. As late as 1900 Scheffauer had written an Ode to Father Mathew for the occasion of a 10,000 gathering of the "League of the Cross" in San Francisco, in memory of the Irish Catholic priest Father Theobald Mathew (1790–1856), who was described as "the great apostle of temperance".[24]

His friendship with the poet George Sterling, a contact encouraged by Bierce, had begun around February 1903, and it brought with it a whole circle of friends including Jack London,[25] Dr. C.W. Doyle,[26] Herman Whitaker, James Hopper, Frederick R. Bechdolt and especially other members of the Bohemian Club, such as the sculptor Haig Patigian, who all regularly met at the Bohemian Grove amid the magnificent red oaks at Monte Rio in Sonoma County, California.

Bierce would later claim his literary "idols" were George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen, and fell out with him much later (as he did with so many of his erstwhile disciples), irritated, as he wrote to him, with "the German ichor in the lenses of your eyes", an early and acute observation from Bierce of Scheffauer's troubled state of being as a hyphenated German-American:"You think your German blood helps you to be a good American. You think it gives you lofty ideals, knowledge, and much else. The same claim could be (and is, doubtless) made for every other nationality. Each tribesman thinks his tribe the best and greatest- even the Hottentot."[27][28]

After his mysterious disappearance in 1913 in Mexico and his presumed death, and despite their estrangement, Scheffauer's devotion to his former master was such that he was responsible for publishing and editing translations of collections of Bierce's short stories in Germany. As with many other American writers, he made Bierce's name known to a fascinated and receptive German literary public: Physiognomien des Todes. Novellen von Ambrose Bierce (1920) which was a translation of In the Midst of Life: Tales of Soldiers and Civilians,[29] and Der Mann und die Schlange: Phantastische Erzählungen von Ambrose Bierce (1922).[30] Scheffauer wrote the introductions to both these collections of short stories. As a satirist, he compared him to Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift and in the German language with Heinrich Heine. He said that the acidity of his merciless humour had been neutralized by his fellow Americans' natural born abhorrence for satire.[31]

Tour of Europe and North Africa 1904–1906

[edit]Ambrose Bierce knew of Scheffauer's plans for a tour of Europe as early as August 1903[32] and invited him to Washington beforehand. He provided him with letters of introduction for the English part of his journey. In July 1904 he left New York and sailed to Glasgow, before that he and Bierce were together in New York for about a month, and they also visited Percival Pollard the Anglo-German literary critic at Saybrook, Connecticut. Scheffauer went on a tour of Europe and North Africa 1904–1906. After about a month in England and Scotland where he cycled or 'wheeled' much, and clearly came to loathe English food, he went to Germany in October 1904 and was mesmerized by Berlin – which he spoke of as "the modern Babylon" and "the Chicago of Europe". He made what was almost a pilgrimage to Jena in Thuringia to see the scientist Ernst Haeckel. He presented Haeckel with works of poetry by his friend George Sterling The Testimony of the Suns and Other Poems (1903) and his own collection of poems Of Both Worlds (1903). He maintained a correspondence with him for over 15 years and would translate some of his works.[33] As the European correspondent for the San Francisco magazine Town Talk in which he regularly sent back accounts of his travels and poems, his tour of the "old world" included Paris, Monte Carlo,[34] Nice, Budapest, Vienna, Munich, Nuremberg,[35] Switzerland, Palermo, Rome, Milan, Turin, Naples,[36] Capri (where he met the romance philologist Alfons Kissner and the German painter and social reformer Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach), Barcelona, Zaragoza, Madrid, Toledo, Corboda, Seville, and Cadiz. He also travelled to Morocco (Tangier), Gibraltar, Algeciras, Granada, Tunisia and Algeria.[37]

First residence in London 1905–1907

[edit]He was back in London in the summer of 1905 where he regularly "mined" the British Museum. He joined the New Bohemian Club at The Prince's Head in the Strand, and drank what he thought was rather tepid English ale with literary figures such as Stephen Phillips, G. K. Chesterton and the poet and parliamentarian Hilaire Belloc.[38]

He met Henry James who he found to be more English than American at a New Year's Eve party at the home of the writer Edmund Gosse.[39] He made a pilgrimage to Plymouth: "From Plymouth, as you know, sailed forth the blue-nosed Puritans to make laws just as blue and to burn witches in Massachusetts." He also studied at Oxford University: "I'm spending a short time up here in this picturesque place of dead creeds and living prejudices. Have been attending special lectures and studying the life. It appears to me like an immense boys' school. There is little of the true scholastic spirit or the impetus of scientific research about the place – nothing compared with the German universities."[40]

In connection with his writings on Haeckel and his enthusiasm for the philosophy of Monism he worked closely with Joseph McCabe, who had translated Haeckel, visiting his home in Cricklewood, north-west London, a number of times, and later writing articles for Charles Albert Watts and the Rationalist Press Association. He continued to publish many short stories and poems in both English and American literary magazines.[41]

He was still in London at the time of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires (April 18, 1906), and as vice president[42] of the San Francisco Architectural Club, and one of James D. Phelan's lieutenants in the movement for beautifying the city, it was reported in Town Talk: "He is vindicating his loyalty to San Francisco in a way that should prove far more beneficial to the city than he could be were he at home. He is acting as a San Francisco promotion committee of one, and through him, since the fire, the readers of some of the European papers are learning more of this city than they ever knew before."[43]

Return to San Francisco and New York 1907–1911

[edit]He eventually returned to San Francisco early 1907. His second major collection of poems Looms of Life was published by Walter Neale in 1908, and in August of the same year his The Sons of Baldur. A Forest Music Drama was performed at the Bohemian Club of San Francisco. The previous year Sterling had been the "Sire" – the term adopted to describe the producer-in-chief of the Grove play – with his own verse drama "The Triumph of Bohemia". As Scheffauer himself explained: "These plays, part masque, part music-drama, part allegory, are a direct outgrowth of the nature-worship of the Californian, and are given in the majestic forest amphitheatre of the club in Sonoma County, amidst colossal redwoods older than the Pyramids. Here my "Sons of Baldur" was produced on a beautiful midsummer night."[44] Sterling's play had depicted a battle between the "Spirit of Bohemia" and Mammon for the souls of the grove's woodmen, Scheffauer's play was unmistakably Wagnerian with the god Baldur slaying the dragon Nidhugg that had been sent by Loki to destroy the woods and worshippers, symbolical of the Bohemians.

He wrote his first novel, Niagara. An American Romance of four generations, finishing it in San Francisco in April 1909. A newspaper report suggested his journey to New York was connected with his novel. "On his way East Mr. Scheffauer will take in the North, in a roundabout way; will visit Seattle, attend the exposition, go on to Niagara Falls and remain there for some time before reaching New York. This young and brilliant author has met with instant appreciation and success."[45] He lived in New York from 1909 to 1911 where he was a "worker" for more than two years at the University Settlement, very little is known about this period. As part of the University Settlement he lived in a house in the neighbourhood of lower east side, where he was clearly inspired to write his very successful play The New Shylock (1912), a study of Jewish-American life that addresses assimilation and acculturation.[46]

Second residence in London 1911–1915

[edit]He moved back to London early 1911 and remained living there until 1915. He married the English poet, Ethel Talbot (1888–1976) who first published a collection of her poems with London Windows (1912).[47] A contemporary review of her work said that in phraseology she follows largely Swinburne and William Ernest Henley.[48] She had written about how to read Poe in 1909 on the 100th anniversary of his birth, and Scheffauer had quoted her words, possibly from some correspondence between them: "The most perfect mood is a fugitive mental weariness that is neither sorrow nor longing; when you come then to Poe the lassitude gives way before the soothing sweetness of his unforgettable melodies".[49]

Scheffauer was struck with this "most excellent advice", as well as her youth and intelligence, already in May 1910 he had proclaimed her: "one of the most gifted as well as youngest of England's poets". He had found not only an English protégé but his Diotima. Scheffauer's romantic notions of love and marriage are contained in a strident epithalamium published in his collection Looms of Life (1908) entitled The Forging of the Rings. Their marriage took place at Highgate, North London on June 25, 1912, where soon after, they also moved into a house, Bank Point, on Jackson's Lane. Satirically reflecting on the outbreak of German spy-mania in England a few years later he would write: "Our house bore little resemblance to the conventional and ugly London villas all arrow. It was just such a place as would have appealed to a German spy, for it commanded a lordly view over all London. Precisely the place to give signals to Zeppelins!"[50] There is a further allusion to another novel he had written in London that has not been traced. A month before he was married it was reported in The Bookman in May 1912 that Scheffauer “has just finished a sort of epic novel of London, which will probably make its appearance this autumn”[51]

International success of his play The New Shylock

[edit]In 1913 his play The New Shylock was performed at Danzig in Germany. The New York Times under the headline: "Danzig Applauds Scheffauer's Play" wrote: "Mr. Scheffauer attended the opening and responded to a number of enthusiastic curtain-calls. The play has already been bought for production in Bonn, Strassburg, and Posen, and negotiations for its production in Berlin are pending."[52] In November 1914 the play was performed at Annie Horniman's Repertory Theatre in Manchester, England, the first American drama ever written and performed at this theatre.[53]

A minor legal battle ensued between Scheffauer (who had the full backing of The Society of Authors) and the Jewish theatrical producer Philip Michael Faraday who attempted to censor some of the text. It was then transferred to London in 1914–15 under the changed title The Bargain. In 1915 it was performed at the Hague and in Amsterdam by the great Dutch actor Louis Bouwmeester (1842–1925)[54] who was well known for his Shylock in William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. In January 1915 it was reported in the London theatrical press that Princess Alexandra Kropotkin had undertaken the adaption of the play for the Russian stage.[55] It was also produced in America at the Comedy Theatre, New York, in October 1915 in which the celebrated English actor Louis Calvert appeared playing the leading role of Simon Ehrlich.[56]

Scheffauer's translations of Heine and Nietzsche

[edit]In London he was a close friend of Oscar Levy, the editor of the first complete edition of Nietzsche's Collected Works (1909–1913) and contributed many English translations of Nietzsche's poems. Some of his Nietzsche translations appeared in his third major collection of poems Drake in California Ballads and Poems (1912). He published his translation of Heinrich Heine's Atta Troll. Ein Sommernachtstraum (1913), with illustrations by Willy Pogany, the Hungarian-American illustrator, who had first illustrated a short story of Scheffauer's in 1906. Levy wrote an introductory essay for it. He knew J. M. Kennedy, and many of that small "crew"[57] of British Nietzscheans[58] and Imagists that also regularly published in The New Age. A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature and Art, edited by A. R. Orage. Of all the British Nietzscheans he was undeniably closest to Horace B. Samuel (1883–1950), who translated a number of Strindberg's plays and eventually Nietzsche's The Genealogy of Morals (1913). H.B.S. had dedicated his first collection of poetry The Arrows of Adolescence (1909) to him: "To my dear friend and poetical mentor Herman Scheffauer I dedicate this book".

In one letter to Ezra Pound, who also contributed regularly to The New Age, he assured him of their spiritual affinity: "Mr. Pound's opinion of things American is, I take it through his confessions, quite as healthy and unabashedly modest as my own."[59] Scheffauer printed here a number of his poems including "The Prayer of Beggarman Death (A Rime Macabre)" and "Not After Alma-Tadema", as well as his English translation of Gabriele D'Annunzio's homage to Nietzsche "Per la Morte di un Distruttore". Following the outbreak of war he used the pseudonym "Attila" and published a number of poems in The New Age. He published many short stories in the leading literary magazines such as Pall Mall, The Strand, The Lady's Realm and T.P.'s Weekly, and appears to have adopted a transatlantic strategy of publishing his stories in both British and American magazines.[60]

Anti-war writings

[edit]Some of his earliest poems The Ballad of the Battlefield (1900), or those from his Of Both Worlds (1903), such as The Song of the Slaughtered, Disarmament and Bellomaniacs, showed that his pacifist tendencies were quite pronounced. In 1906 in an article he wrote for the London Westminster Review, entitled The Powers Preservative of Peace, he had even advocated an entente cordial between England and Germany. England ought to seek her "natural ally ... in a race and nation more closely related in all essential and significant points."[61] In 1925 he declared: "War is the most terrible hostage of mankind. My voice has always been loud for peace, long before it became a passion, a mode or a necessity to be a pacifist. I have not only spoken for peace, I have even fought against war."[62] In one of his rare science fiction short stories, "The Rider Through Relativity" (1921) the European battlefields of Flanders and the Champagne in World War I are seen through a reversed chronology narrative.[63]

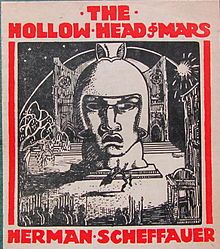

His visionary expressionist play The Hollow Head of Mars: A Modern Masque in Four Phases appeared in April 1915, but we know that it had already been finished in 1913. Written in staccato blank verse he said that it was not "an insurrectionary experiment in vers libre" and that "It is useless to seek for parallels between the nations actually at war and these visionary combatants". His play had predicted the war and had seen through the hidden mechanisms that had encouraged its unfolding, depicting the sleepwalkers listening to the artificially produced voice of Mars, it is one of his most important but neglected works. The character of the 'Mountebank' is clearly presented as a Mephistophelean figure, whispering affectionately into the ear of 'The Minister of War' and gleefully drinking every drop of blood in his beaker and toasting "To Liberty". It is a character that is deliriously happy at the increasing numbers of soldier recruits that join him, their blood as the Minister says: "... shall manure The lilies of peace."[64] This macabre play on war shows him as a true protégé of Bierce, who had written some astonishing short stories about the American Civil War. After the onset of the First World War throughout 1914–1917, during America's phase of neutrality, his articles sent from London back to the New York-based American pro-German magazines, under the aegis of the German-American Literary Defense Committee (GALDC), were widespread and numerous, it was here that he "fought against war" and attempted to influence America's position. He wrote chiefly for The Vital Issue (edited by Francis J.L. Dorl[65]) and The Fatherland (edited by George Sylvester Viereck who Scheffauer had known in New York literary salons since late 1909[66])

The flight to Amsterdam and Berlin, 1915

[edit]Increasingly concerned about the anti-German riots in England[67] and his "furrin" looking name, as well as having already received a visit from a Scotland Yard detective to his house,[68] he left London with his wife for Berlin via Amsterdam in March 1915. He wanted to familiarize himself with the circumstances in Germany and "better orientate himself" so that he could write more convincingly, and was seriously considering returning to America. However, after finding a flat in Berlin-Friedenau he was soon appointed editor[69] of the pro-German American newspaper, The Continental Times: A Cosmopolitan Newspaper published for Americans in Europe, which was published three times a week. It boasted of sales in Austria, Italy, Switzerland, United States and the Netherlands and proclaimed itself on its headed paper as "The Leading Newspaper for Americans on the Continent".[70]

Writing for this newspaper he continued to use the pseudonym 'R.L. Orchelle'. He was a close friend and colleague of the Irish nationalist Roger Casement in Berlin, who also wrote for the newspaper. His most ferocious attacks were reserved for President Woodrow Wilson, whom he later called "the most despicable miscreant in history, – a man whose incapacity, dishonesty and treachery brought about the most terrible failure in human history" calling him "... a new kind of monster – a super-Tartuffe, unimagined even by Moliere, unachieved even by Shakespeare."[71] As early as October 1915 he described Theodore Roosevelt as " a bloodthirsty demagogue" who was "openly inciting with a fanaticism that amounts to delirium".[72]

Scheffauer was indicted in the United States in absentia for treason in November 1919, and it was for his work at The Continental Times that was cited as the main reason, despite the fact that he had resigned his position as literary editor in December 1916 before the United States had even entered the war. In March 1916 he had been attacked in The New York Times as one of a triumvirate of American poets (together with Ezra Pound and Viereck) who had turned their backs on their country: "In childish wrath they seek a foreign shore;/There, turning on the land they loved before,/They smear foul rhymes upon her honoured name ...".[73] It was a letter to J.M.(John McFarland) Kennedy, the English translator of Nietzsche, that was cited by the federal grand jury as an example of his treason:

You say that I turned upon a country to which I professed allegiance in favor of a country now its deadly enemy. I have never professed allegiance to any country. To England I owe none. To America, as a born citizen, I owed it only according to the dictates of my conscience. I oppose the policy of America now- or that of the powers which have my unfortunate country in thralls – as I have always opposed the English policy which dictated it, because I knew it to be hopelessly, damnably wrong ... The ultimatum presented to Wilson from Wall Street and the war profiteers, and its acceptance, constitute the most infamous betrayal of a nation that the world has ever seen.[74]

His friend, the writer and publisher Ferdinand Hansen congratulated him:

“...a few days ago I received word from Mr. Scheffauer that he had been indicted on a charge of “treason” for certain articles he had written! I congratulate my friend Scheffauer. He cannot consider this absurd charge a stigma to his name, but only a tribute to the power and brilliance of his pen. No writer has fought more passionately, more fearlessly for truth and fair play than he. His articles have been a constant source of strength and inspiration to me during these years of darkness and despair. He tore the sophistries of certain English intellectuals– such as H. G. Wells, Gilbert K. Chesterton and John Galsworthy to shreds and exposed the hypocrisies and falsehoods of the Entente politicians with merciless irony...”[75]

Scheffauer never returned to the United States or to England where he had much earlier been placed on a blacklist. The notorious English populist editor and publisher and independent MP Noel Pemberton-Billing, renowned for his anti-German homophobia and anti-Semitism,[76] as early as November 1916 on the floor of the House of Commons had brought attention to Scheffauer’s journalism in The Continental Times and “to the articles containing abuse of all things British”. He goaded a reluctant Lord Robert Cecil, then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, with confused questions concerning the issuing of passports to Scheffauer and his departure from England, “Will the Noble Lord give an undertaking that Hermann Scheffauer, who is stated to be on terms of intimacy with members of the Government, will not be permitted to return to this country?”. Lord Robert Cecil obliged him: ”Yes; I think I can safely give that promise.”[77] The irony of being a persecuted poet and writer forced into exile could not have escaped him, he had translated Heinrich Heine's own introductory words written in 1841 to his great comic masterpiece Atta Troll, "I am therefore celebrating my Christmas in an alien land, and it will be as an exile in a foreign country that I shall end my days".[78] He wrote a trilogy of critical works on the theme of America (1923–25) believing that America was a natural 'biological' connecting link, or 'Bridge', between Germany and England. His only child was a daughter, Fiona Francisca Scheffauer (born circa 1919).[79]

Friendship with Thomas Mann

[edit]In April 1924 Scheffauer wrote about Thomas Mann's "crisp, skeptic, [and] collected mind ... a mind almost pedantic in its precision of expression, its tortuous searching for the exact word, the luminous phrase. Mann, who might in his externals pass for an English M.P. or a youngish major ..."[80] His wife had also interviewed him. He had by then already translated Thomas Mann's Herr und Hund which had appeared in The Freeman (1922–23) in six instalments, it was then published as a book Bashan and I. Translated by H. G. Scheffauer. (Henry Holt, New York, 1923).

Scheffauer was aware in July 1924 that Mann was close to finishing his "... study of a sick man in the environment of an Alpine sanatorium" and Mann wanted to entrust him with the translation of this novel Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain), but failed, due to the opposition of his American publisher Alfred A. Knopf who was clearly influenced by the literary judgement and financial incentive of the London publisher Martin Secker to share translation costs if Scheffauer was not chosen.[81] The Magic Mountain was translated instead by Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter. Scheffauer translated Mann's Unordnung und frühes Leid (Disorder and Early Sorrow) that appeared in the American literary journal The Dial. Following Scheffauer's death in 1927 Knopf published in 1928 Children and Fools as the seventh volume of Mann's work in English translation, which consisted of nine stories all translated by Scheffauer, covering a period from 1898 to 1926. The blurb said: "Each work hitherto put into English represents Thomas Mann at one fixed point of his evolution as an artist. Children and Fools outlines, for the first time, that evolution as a process, and enables the reader to trace in one volume more than a quarter-century of the growth of as extraordinary a mind as our age is likely to know." In November 1926 it was reported that he had just finished writing a new play entitled: "Pan Among the Puritans".[82]

Romane der Welt

[edit]Scheffauer and Thomas Mann had a collegial, friendly relationship.[83] He acknowledged his translation skills and looked upon him as an authority in Anglo-American literature.[84] Scheffauer told Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche in 1924 that Mann had assured him that he much preferred reading his English translation of Herr und Hund rather than the original German.

In April 1927, they launched a series Romane der Welt (Novels of the World), that was published by Thomas Knaur Nachfolger Verlag in Berlin. Each week a novel that cost only 2,85 Marks appeared in the RdW series, on the back of the dust-jacket it proclaimed in German: "Every Friday a new volume/Every novel an experience". It included authors such as Herman Melville's Moby Dick oder Der Weisse Wal and Taipi and Cashel Byrons Beruf by George Bernard Shaw (with forewords by Scheffauer); works by Hugh Walpole (with a foreword by Thomas Mann), Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, P. G. Wodehouse, John Galsworthy, Radclyffe Hall, Arnold Bennett, Francis Brett Young and Liam O'Flaherty.

The choice of American literature very much reflecting his ideas he gave in a key lecture at the University of Berlin in 1921 and contained in his chapter on 'Art and Literature' in his first work on America Das Land Gottes (God's Own Land) (1923), thus, the work of his friend Sinclair Lewis Die Hauptstrasse (Main Street) and Babbitt, appeared in the series, of which he had previously written: "These books reveal the worm gnawing at the heart of American life, the inner doubt and unhappiness, the unhappiness which results from the hollowness within and the shallowness of life without- and which seeks to distract itself by a ceaseless external activity."[85] Novels by Joseph Hergesheimer such as Java Head; and Tampico (also with a foreword by Scheffauer), Floyd Dell, "George Challis", the pseudonym of Max Brand, Lesley Storm and Mary Borden, as well as many westerns by Zane Grey. German works published in RdW were by Eugen Binder von Krieglstein and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer. The series also included French, Spanish, Swiss, Canadian, Swedish and Brazilian authors. The democratic intent of the series was palpable, and it was attacked in some conservative literary circles as unnecessary "flooding" of the German market. Mann wanted his Buddenbrooks to appear in the RdW in 1926.[86] He thought it was quite unique, and from a social point of view something remarkable, he wanted his novel "to be thrown into the wide masses in a series of classical works of world literature in a popular edition" but his publisher Fischer, rejected the idea.[87] Scheffauer was present at the first meeting of the German PEN-Group on December 15, 1924, that had named Ludwig Fulda as its first president, and he was also a close friend of Walter von Molo.[88]

Berlin Correspondent for The New York Times

[edit]Herman and Ethel Scheffauer both contributed regularly to The Bookman: An Illustrated Magazine of Literature and Life providing fascinating details about the German literary and publishing world. They also both wrote regularly for the English monthly edition of the Berliner Tageblatt. Scheffauer was also the Berlin correspondent for The New York Times, as well as some other leading American newspapers, and he worked tirelessly as a literary agent for a number of British and American publishing companies. In 1925, eleven of his short stories were published in German translation Das Champagnerschiff und andere Geschichten (Berlin, 1925). He had already published the story that he gave as its main title "The Champagne Ship" back in January 1912 in New York in one of Frank Munsey's so-called "pulp magazines", The Cavalier and the Scrap Book.[89]

Scheffauer never relinquished his original vocation as both poet and architect, he regarded words as things with which to build. His love of architecture in the 1920s was reaffirmed again with articles on Erich Mendelsohn, Walter Gropius, Hans Poelzig, Bruno Taut and the Bauhaus movement. Scheffauer played an important role in describing some of the contemporary art-movements in Germany for a wider English and American audience and his unique position was his personal acquaintance with these same figures. This is apparent from the collections of essays that he published in his The New Vision in the German Arts (1924), a work that received acclaimed reviews in America, particularly for its attempts to communicate to an English speaking audience the meaning of expressionism in German literature and poetry. Scheffauer also wrote considerably on German expressionist cinema such as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922), and much later Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927).[90] He wrote passionately about film and praised it as "a new stereoscopic universe" where space had been given a new voice in a "cubistic world of intense relief and depth".[91] As both poet and architect he would write on this Vivifying of Space:

Space – hitherto considered and treated as something dead and static, a mere inert screen or frame, often of no more significance than the painted balustrade background at the village photographer's - has been smitten into life, into movement and conscious expression. A fourth dimension has begun to evolve out of this photographic cosmos.[92]

The architectural historian, Anthony Vidler[93] has written: "Scheffauer anticipates all the later commonplaces of expressionistic criticism from Siegfried Kracauer to Rudolf Kurtz."[94] His aesthetic and sociological criticism was tinged with his own incomplete attempt at "de-Americanisation" ["weil er nicht gänzlich ent-amerikanisieret ist"] – as his friend Oscar Levy once put it,[95] and it was also very clear to Levy that Scheffauer still retained a fair share of American puritanism that so animated all of his criticism. Scheffauer's collection of essays: The New Vision in the German Arts (London,1924) was testimony to this unique German-American poetical and philosophical sensibility.[96]

Scheffauer's suicide 1927

[edit]Scheffauer killed himself and Katherine von Meyer, 23, his private secretary, in 1927 at the age of 51 years.[97] It was a horrific act of mental derangement brought on at a time when he was suffering from an extreme depression. Scheffauer cut his own throat and hurled himself from the window of his third storey flat; a search of his home quickly discovered the body of his secretary, apparently murdered by a single stab wound to the breast.[98] He wrote to his wife shortly before he killed himself, who was staying with their daughter at their villa at Dießen am Ammersee, Bavaria, that he was in great "mental torment", and that each autumnal day it felt as if he was "... suffering the death of ten thousand mortal agonies". A couple of letters between Scheffauer and his wife were published (in German translation)[99] to scotch some of the rumours that had arisen in the press about their own relationship and of the moral integrity of his secretary.

The PEN Club of Berlin, of which he was a founding member and its secretary, held a memorial service for him on October 27 together with a madrigal choir. Karl Oscar Bertling the director of the Berliner Amerika-Institut at the University of Berlin, gave a speech and spoke of Scheffauer's "poetic mission" (dichterische Sendung) and his "artistic priestliness" (kunstlerisches Priestertum). Thomas Mann also attended and in his speech praised his ability as a translator of his works and attempted to explain his unhappiness at the end of his life, of which he admitted he had not the slightest idea, he thought it was due to the nature of his "undomiciled internationality" (der unbeheimateten Internationalität).[100] The American writer Sinclair Lewis also gave a passionate speech at this memorial service for his "friend in struggle". According to newspaper reports, his body was transferred to Dießen am Ammersee, where he was buried. It was here and the German geographical beauty of the place, that despite his political banishment from California, he said he had in certain respects rediscovered San Francisco.

Selected works

[edit]Poems, stories and plays:

- The Isle of the Dead. In: Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, January, 1900

- Of Both Worlds: Poems. A. M. Robertson, San Francisco 1903

- Looms of Life: Poems. The Neale Publishing Company, New York 1908

- Drake in California: Ballads and Poems. A. C. Fifield, London 1912

- The Ruined Temple, 1912 (Online edition)

- The Masque of the Elements, J. M. Dent & Sons, London and E.P. Dutton & Co., New York 1912 (Online edition)

- Der neue Shylock. Schauspiel in vier Akten, Berliner Theaterverlag, Berlin 1913

- The Hollow Head of Mars. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd., London 1915

- Atlantis, London in Snow, Manhattan, undated (Online edition)

Selected short stories:

- The Arrested Stroke. In: Macmillan's Magazine, April, 1906

- The Black Fog. In: The Atlantic Monthly, February, 1908

- Hate. In: The Pall Mall Magazine, May, 1913

- The Thief of Fame. In: Harper's Magazine, August, 1913

- The Path of the Moth. In: The Smart Set, April, 1914

- Das Champagnerschiff und andere Geschichten, Ullstein Verlag, Berlin 1925

Translations

[edit]- Friedrich Nietzsche: Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 17, 1911

- Heinrich Heine: Atta Troll, 1913

- Rosa Mayreder: Zur Kritik der Weiblichkeit, 1913

- Gabriele D'Annunzio: On the Death of a Destroyer. Friedrich Nietzsche, XXV August, MCM. From the Italian of Gabriele D'Annunzio. By Herman Scheffauer., in: The New Age, Vol. 16, 1915

- Ernst Müller-Meiningen: "Who are the Huns?" The Law of Nations and its breakers, 1915

- Rudolf Herzog (1869–1943): The German Road to Rome, 1915

- Bernhard Kellermann: The Great Battle of Loos, 1915

- Paul Barchan (1876–1942): When the Pogrom Came, 1916

- Friedrich Stampfer: From Versailles to Peace!, Berlin, 1920

- Siegfried Mette: The Treaty of Versailles and other peace treaties of the era Napoleon-Bismark, 1921

- Bruno Taut: Architecture in the New Community, in: The Dial,1921

- Allemand Daudet: Tartarin on the Rhine, 1922 [i.e. the pseudonym for Max Joseph Wolff (1868–1941)]

- Thomas Mann: Bashan and I, 1922/23

- Otto Braun (1897–1918): Diaries of Otto Braun, in: Freeman 1923

- Georg Kaiser: Gas, 1924

- Eric Mendelsohn: Structures and Sketches, 1924

- Klabund: Peter the Czar, 1925

- Leo Tolstoy: Letters from Tolstoi, 1926

- Hermann Karl Frenzel: Ludwig Hohlwein,1926

- Thomas Mann: Children and Fools, 1928

- Thomas Mann: Early Sorrow, 1930

Essays

[edit]- Haeckel, A Colossus of Science, in: The North American Review, August, 1910

- Nietzsche the Man, in: Edinburgh Review, July, 1913

- A Correspondence between Nietzsche and Strindberg, in: The North American Review, July, 1913

- Whitman in Whitman's land, in: The North American Review, 1915

- Woodrow Wilsons Weltanschauung, in: Deutsche Revue, April–Juni, 1917

- The German Prison-House. How to Convert it Into a Torture-Chamber and a Charnel. Suggestions to President Wilson, Selbstverlag des Verfassers, Berlin 1919.

- The Infant in the Newssheet. An Ode against the Age, The Overseas Publishing Company, Hamburg 1921

- Blood Money: Woodrow Wilson and the Nobel peace prize, The Overseas Publishing Company, Hamburg 1921

- The Lear-Tragedy of Ernst Haeckel, in: The Open Court, 1921

- Das Land Gottes. Das Gesicht des neuen Amerika, Verlag Paul Steegemann, Hannover 1923 [It was dedicated to his friend John Lawson Stoddard "Meinem teuren Freunde John L. Stoddard dem Vorbild edelsten Amerikanertums gewidmet"] (translated into German by Tony Noah)

- Joaquin Miller, der Dichter der Sierras, in: Deutsche Rundschau, January, 1923

- The New Vision in the German Arts, Ernest Benn, London 1924

- The Work of Walter Gropius, in: Architectural Review, July, 1924

- Das geistige Amerika von heute, Ullstein Verlag, Berlin 1925

- Wenn ich Deutscher wär! Die Offenbarungen eines Amerikaners über Deutschlands Größe und Tragik, Verlag Max Koch, Leipzig 1925 (translated into German by B. Wildberg)

- "Stone Architecture of Man and the Precisely Wrought Sculpture of Nature", in: World Review Incorporated, April, 1927

Works about Scheffauer

[edit]- Heinz J. Armbrust, Gert Heine: "Herman George Scheffauer", Wer ist wer im Leben von Thomas Mann. Ein Personenlexikon. Verlag Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt 2008, p. 247; ISBN 978-3-465-03558-9

- Vivian, John Christopher: “eine Propaganda der Liebe und des Lichtes…”: On the Reception of Haeckel’s Popularization of Science in California around 1900 : The San Francisco ‘Bohemians’ as Haeckel’s American Disciples. In: Haeckels ambivalentes Vermächtnis. Halle (Saale), Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart 2023 S. 53–99. (= NAL-historica).Online unter: https://levana.leopoldina.org/receive/leopoldina_mods_00828.

- Online Archive of California: Herman George Scheffauer Photograph Album, ca. 1885–ca. 1925 (Short biography, selected bibliography and photographs)

- The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley: Photograph of Hermann Georg Scheffauer and his wife Ethel Talbot, undated

- Herman George Scheffauer papers, 1893–1927 BANC MSS 73/87 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Correspondence, manuscripts and other writings of Herman George Scheffauer. A good portion of the material pertains to Scheffauer's mentor, Ambrose Bierce (including copies of Bierce's correspondence with Dr. C.W. Doyle). The letters from Bierce to Scheffauer include references to Jack London, George Sterling and other writers (and include transcriptions as well as originals). Also included in the collection is a small amount of correspondence and writings of Scheffauer's wife, Ethel (Talbot) Scheffauer.[101]

- Herman George Scheffauer Photograph Album, ca. 1885–ca. 1925. The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. The Herman George Scheffauer Photograph Album contains 130 photographs taken circa 1885–1925. Nearly all the photographs in the album feature Scheffauer, many of them being portraits taken by professional photographers in San Francisco, London, and Berlin. Other notable persons featured in the collection include Ambrose Bierce, George Sterling, Haig Patigian, James Hopper, Frederick Bechdolt, as well as Scheffauer's wife, Ethel, and their daughter, Fiona. Identifiable locations featured in the collection include the Bohemian Grove, London, Scotland, Spain and Germany. A few of the photographs feature sculptural or painted portraits of Scheffauer.

- There are 93 letters of Scheffauer to H.L. Mencken (1921–1927) amongst the H.L. Mencken papers 1905–1956 (MssCol 1962) in the New York Public Library, Archives & Manuscripts.

References

[edit]- ^ Who's Who in America: a Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living Men and Women of the United States. 1908–1909.

- ^ The National Cyclopædia of American Biography, Vol. 57, p. 611.

- ^ "Scheffauer, Philipp Jacob", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 30 (1890), S. 672–676 (Onlinefassung)

- ^ "Die Tragodie eines Publizisten. Der Schriftsteller Hermann George Scheffauer ersticht seine Sekretaerin und veruebt Selbstmord. Die Motive bisher unbekannt", Hamburger Anzeiger (8 October 1927), p. 4.

- ^ Scheffauer in: Was wir Ernst Haeckel verdanken. Ein Buch der Verehrung und Dankbarkeit, 2 Bde. Hrsg. v. Heinrich Schmidt (Leipzig, 1914), 2, S.75.

It is highly probable that Scheffauer had read the serialisation of James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man that, with Ezra Pound's assistance, had originally appeared in The Egoist (1914–1915). Heinrich Schmidt translated Scheffauer's English essay into German. - ^ "Ascending Mt. Olympus". Johnnycomelately.org. October 3, 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ Herman Scheffauer. "How I Began", in: T. P.'s Weekly (April 3, 1914, p. 419).

- ^ Was wir Ernst Haeckel verdanken. Ein Buch der Verehrung und Dankbarkeit, 2 Bde. Hrsg. v. Heinrich Schmidt (Leipzig, 1914), 2, S.77."Ich war jetzt in jener unglücklichen, jugendlichen Periode von idealistischer Schwärmerei und Byronscher Romantik, durch welche alle, besonders die mit phantasievollen gemüt, hindurchgehen müssen."

- ^ "1906 Earthquake and Fire". sfmuseum.net. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Who's who in America (1908), vol. 5, p. 1663.

- ^ Was wir Ernst Haeckel verdanken, op. cit, S.76.

- ^ "Ich führte gegen sie flammende Stellen aus dem durch und durch düsteren Werk Youngs, den "Nachtgedanken", an." op. cit., S.77.

- ^ a b Was wir Ernst Haeckel verdanken, op. cit., S. 77.

- ^ See John Vivian (2023) “eine Propaganda der Liebe und des Lichtes…”: On the Reception of Haeckel’s Popularization of Science in California around 1900 : The San Francisco ‘Bohemians’ as Haeckel’s American Disciples. In: Haeckels ambivalentes Vermächtnis. Halle (Saale), Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart. S. 57–70; 77–88. (= NAL-historica).,

- ^ "The Riddle Of The Universe". Watts And Company. January 1, 1934. Retrieved August 17, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ See Scheffauer's article "The Poetry in Our Path", in: Out West [Los Angeles, Cal.] New Series Vol. 2, June, 1911, Number 1, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Edward F. O'Day, "The Poetry of San Francisco", The Lantern. Edited by Theodore F. Bonnet and Edward F. O'Day, Vol. 3. No. 6, September 1917, p. 176.

- ^ The Call (San Francisco), Vol. 74, Number 179, November 26, 1893.

- ^ a b See Carroll D. Hall, Bierce and the Poe hoax. With an Introduction by Carey McWilliams (San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1934.)

- ^ Walter Neale, Life of Ambrose Bierce (New York, 1929), p. 222. Poe also said of Moore's "Melodies" and the lines beginning:"Come, rest in this bosom." that "The intense energy of their expression is not surpassed by anything in Byron." Poe also acclaimed his imaginative qualities in opposition to Coleridge. See the essay "The Poetic Principle" and Poe's review of Moore's 'Alciphron' in: "Tom Moore: Fancy and Imagination" both in: The Fall of the House of Usher, and other Tales and Prose Writings of Edgar Poe. Ed. by Ernest Rhys (London: Walter Scott Ltd., 1920), pp. 253, 299–301.

- ^ AB to HS, August 4, 1903, p. 110.

- ^ The San Francisco Examiner, 8 Aug. 1897, p. 18.

- ^ Ambrose Bierce to Herman Scheffauer, February 12, 1904, A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce. Edited by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (The Ohio State University Press, 2003), p. 118.

- ^ See The San Francisco call., Sunday, October 28, 1900, p. 28.

- ^ Scheffauer went sailing with him on his yacht 'Spray'. See Alex Kershaw, Jack London: A Life (St. Martin's Griffin, 2013), p. 131.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Dr. Charles William Doyle (1852–1903)

- ^ Ambrose Bierce to Herman Scheffauer, Washington, November 11, 1903, A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce. Edited by S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (The Ohio State University Press, 2003), p. 115

- ^ Roy Morris, Ambrose Bierce. Allein in schlechter Gesellschaft. Biographie. Haffmans Verlag, Zürich 1999, pp. 347, 370.

- ^ Joshi, S. T. and Schultz, David E. Ambrose Bierce: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary Sources. Westport, CT. and London, Greenwood Press, 1999, pp. 20–21.

- ^ See Friedel H. Bastein, "Bierce in the German-Speaking Countries (1892–1982); A Bibliography of Works by and about Him", in: American Literary Realism, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (Spring–Autumn 1985), p. 231.

- ^ Scheffauer "Amerikanische Literatur der Gegenwart", in: Deutsche Rundschau, Vol. 186, 1921, p. 221.

- ^ "When am I to see you on your way to Europe?" AB to HS, August 4, 1903, in: A Much Misunderstood Man: Selected Letters of Ambrose Bierce. Edited by S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (The Ohio State University Press, 2003), p. 109.

- ^ See Vivian (2023) passim

- ^ "Thus It Befell at Monte Carlo", The Pacific Weekly, Vol. XIV. No. 698, San Francisco, January 13, 1906, pp. 7, 38-39.

- ^ His stay in Nuremberg inspired him to write the poem "The Iron Virgin in the Five-Cornered Tower "(1905)

- ^ Scheffauer later wrote about his experience in Naples climbing Vesuvius: See Scheffauer "A Victory over Vesuvius", in: Macmillan's Magazine, Vol. 1. New Series November 1905 to October 1906, pp. 613–616. "That morning in February I awoke and found all Naples white with snow. Such a thing, said the natives, had not occurred for twenty years."

- ^ See "Scheffauer's Letters", in: Town Talk, Vol. 14., (Saturday, September 16, 1905), p. 12.

- ^ Belloc had visited California in 1890 and returned again in 1896 where, at Napa, he married an American, Elodie Hogan.

- ^ "In the Heart of Literary London", Town Talk, Vol. XIV. No. 700, Saturday, January 27, 1906, p. 13.

- ^ Town Talk, Vol. XIV. No. 724, San Francisco, July 14, 1906, p. 10.

- ^ The Literary Writings in America: A Bibliography (1878–1927), (Kto Press a U.S. Division of Kraus-Thomson Organisation Limited, Millword, New York, 1977), Vol. 7 Rafinesque-Szymanowiki, pp. 8826–8830.

- ^ In the San Francisco Architectural Club – Yearbook 1909 (1909)(Online: https://archive.org/stream/sanfranarch1909unse#page/n5/mode/2up ) his name is entered under "Leave of Absence", p. 20.

- ^ See Scheffauer's "The City Beautiful-San Francisco Rebuilt", The Architectural Review A Magazine of Architecture the Arts of Design, Vol. XX, No. 117, August 1906.

- ^ "How I Began", T.P.'s Weekly, April 3, 1914, p. 419.

- ^ Santa Cruz Sentinel, Santa Cruz, California, May 26, 1909, p. 3.

- ^ Town Talk reported: "Scheffauer laid the scene of his tragedy "The New Shylock" in the New York Ghetto. The drama was translated into German by Leon Lenhard, the German translator of John Galsworthy's plays and stories. It was presented at the Municipal Theatre of Danzig last week, and registered an immediate hit. Scheffauer was present at the premiere and in response to repeated cries of "Author!" appeared before the curtain and made a graceful speech. Arrangements are now under way to have the play produced in Bonn, Strassburg and Posen, and a Berlin production will probably follow. Later on "The New Shylock" will be presented in New York." "Scheffauer's Success", in: Town Talk, Vol. 22,(October 25, 1913), pp. 11–12.

- ^ "Herman and Ethel Talbot Scheffauer". cdlib.org. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ The Athenaeum, No. 4406, April 6, 1912, p. 364.

- ^ "The Baiting of Poe ", in: Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, Vol. LIII – Second Series January–June 1909 (06-01-1909), p. 191

- ^ See "London in August, 1914. Sleuth-Hound" and "Spy. By R. L. Orchelle", Issues and Events. A Weekly Magazine, pp. 179–181.

This was originally published in The Continental Times. - ^ The Bookman, May 1912, p. 51.

- ^ October 12, 1913

- ^ Henry George Hibbert, "Fight on "The New Shylock."", in: The New York Clipper. Oldest Theatrical Journal in America. Founded in 1853 by Frank Queen, 'Our London Letter' (December 5, 1914), p. 2.

- ^ See Hayden Church, in: The Illustrated Buffalo Express, (Sunday, June 3, 1915): "... In Scheffauer's absence his agent sold the Dutch rights to Louis Bouwmeester the talented Dutch actor-manager who produced the piece forthwith. Under the title of Simon Lusskin it appears to have scored a big hit. Bouwmeester, in fact, has turned 'em away with it both at The Hague and in Amsterdam and royalties are flowing in ..."

- ^ The Globe, Saturday 23 January 1915, p. 5.

- ^ See "Death Of Louis Calvert." The Times [London, England] (20 July 1923), p. 14.

- ^ "The Nietzsche Movement in England: A Retrospect, a Confession, and a Prospect", The New Age (December 26, 1912), p. 181.

- ^ On Levy, see Dan Stone, Breeding Superman. Nietzsche, Race and Eugenics in Edwardian and Interwar Britain, Liverpool University Press, 2002, pp. 12–32.

- ^ "Through Alien Eyes", The New Age, February 6, 1913, p. 335

- ^ There is no modern bibliography of Scheffauer's works.

- ^ Scheffauer quoted in "The Peace Movement", The Review of Reviews (August 1906) 34, 200, p. 161.

- ^ Wenn ich Deutscher wär!, 1925, S.33. Cf. "My pen still spoke for Peace. Always it wrought for Reason./Still it obeyed Truth's mystic gravity – A loyal needle in and out of season/"Scheffauer, Infant, 1921, p. 23.

- ^ The short story was published in The Double Dealer, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March, 1921), pp. 90–98. Cf. Andy Sawyer "Backward, Turn Backward: Narratives of Reversed Time in Science Fiction," in: Worlds Enough and Time: Explorations of Time in Science Fiction and Fantasy. Ed. edited by Gary Westfahl, George Slusser and David A Leiby (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2002)

- ^ The Hollow Head of Mars by Herman Scheffauer, Author of The New Shylock, The Sons of Baldur, etc. (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd. 4, Stationer's Hall Court, E.C. 1915), 'The Third Phase', p. 46.

- ^ On Dorl's correspondence with Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff and later internment, see Jörg Nagler, Nationale Minoritäten im Krieg "Feindliche Ausländer" und die amerikanische Heimatfront während des Ersten Weltkriegs (Hamburg, 2000), 517.

- ^ See "NO UNION, SALON FOR POETS ..."in: The New York Times (Feb 24, 1910); p. 18.

- ^ See Panikos Panayi, "Anti-German Riots in London during the First World War", in: German History, Vol. 7, Issue 2, 1989, pp. 184–203.

- ^ See "London in August, 1914. Sleuth-Hound and "Spy. By R. L. Orchelle", in: Issues and Events. A Weekly Magazine, pp. 179–181.

- ^ The New York Times called him a "sub-editor", whereas the Military Intelligence Bureau in Washington said he was the "editor", Scheffauer described himself as literary editor.

- ^ The Continental Times, (Wednesday, July 26, 1916), p. 1.

- ^ Blood Money: Woodrow Wilson and the Nobel peace prize, 1921, p. 9.

- ^ Preface to Ernst Müller-Meiningen: "Who are the Huns?" The Law of Nations and its breakers, 1915. Signed R. L. Orchelle, Berlin, Oct. 25. 1915

- ^ Schauffler, Robert Haven. "The Poets Without a Country", The New York Times, March 5, 1916.

- ^ 'POET HELD A TRAITOR: Herman Scheffauer Indicted for Hun Propaganda. Open Letter Denounces U.S. His Sympathies With Germany. Californian Wrote of "Serfdom of America" – Pro-German Literature Strewn Over Allied Battle-Lines by Enemy Ballons", The Washington Post, January 9, 1919, p. 1.

- ^ An Open Letter to An English Officer and Incidentally to The English People.(Overseas Publishing Co. Hamburg, 1921), pp. 51–52.

- ^ „Pemberton-Billing used his papers, the Vigilante and the Imperialist, to promote his view “that the British war effort was being undermined by the ‘hidden hand’ of German sympathizers and German Jews operating in Britain,” and that the weapons of choice of those he liked to call “the Shylocks of Frankfurt” and “the Ashkenazim” were prostitution and homosexuality.” Cited in Erin G. Carlston, Double Agents Espionage, Literature, and Liminal Citizens (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), p. 34.

- ^ HANSARD 21 November 1916, Commons Sitting. ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS. FOREIGN OFFICE PASSPORTS (HERMANN SCHEFFAUER). HC Deb 21 November 1916 vol 87 cc1182-3 1182.

- ^ Atta Troll. From the German of Heinrich Heine by Herman Scheffauer. With Some Pen-and-ink Sketches by Willy Pogàny. (With an Introduction by Dr. Oscar Levy.).(London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1913), p. 27.

- ^ The birth of his daughter Fiona Fransica is mentioned in his Ode in the context of his indictment, See: The Infant in the News=sheet: An Ode Against the Age (1921), "In her birth came to me a second birth/ And in my days of loss a glorious dower./ O exile's daughter/ That saw the dark at New Year in Berlin/ The child of one they charged with treason rank/ And sought to blacken with the spoor of sin/ Whose guilt was write in water/ By courts that in their corruption stank/. ... ."(pp. 16–17)

- ^ "A Panorama of German Books by Herman George Scheffauer", in: The Living Age, July 12, 1924, pp. 72–75.

- ^ See Tobias Boes, Thomas Mann’s War: Literature, Politics, and the World Republic of Letters. (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2019), p. 66.

- ^ T.P.'s & Cassell’s Weekly, Nov. 20, 1926, p. 134. (What They Tell Me)

- ^ Armbrust, Heinz J. & Gert Heine: "Herman George Scheffauer", Wer ist wer im Leben von Thomas Mann. Ein Personenlexikon. Verlag Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt 2008, pp. 57, 247.

- ^ "Ich hatte den Mann persönlich gern, ich war ihm dankbar, weil er mehrere meiner Arbeiten mit außerordentlicher Kunst und Liebe ins Englische übersetzt hatte, zudem galt er als ausgezeichneter Kenner der angelsächsischen Literaturen." [Thomas Mann GW 11: 760–1]

- ^ "Dieser Bücher zeigen den Wurm, der am Herzen des amerikanischen Lebens nagt, den tiefen Zweifel und die Unseligkeit, die aus der inneren Hohlheit und äußeren Flachheit des Lebens entspringt und die sich in unaufhörlicher äußerer Tätigkeit zu zerstreuen sucht. Scheffauer, Das Land Gottes. Das Gesicht des neuen Amerika (1923), S. 189.

- ^ See Reinhard Wittmann, Geschichte des deutschen Buchhandels. Ein Ueberblick (München: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1991), X. Der Buchhandel in der Weimarer Republik, S.310–311.

- ^ Ernst Fischer, Bd. 2, Thl. 1, S.296. The letter is reprinted in Gottfried Bermann Fischer, Bedroht-bewahrt. Der Weg eines Verlegers. (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 1967), S.66-69.

- ^ Unpublished letter of Walter von Molo to Scheffauer (Berlin, 25.1.1926) See Autographen Deutschland - Das Fachantiquariat für Originalhandschriften http://www.autographen-deutschland.com/angebote.php?name=scheffauer&price=&submit=Suchen&page=2

- ^ The Cavalier, (January 6, 1912)

- ^ "An impression of the German film Metropolis", New York Times, March 6, 1927, pg. 7.

- ^ "Cubism on the Screen", The New York Times, November 28, 1920, p. 79.

- ^ Scheffauer, "The Vivifying of Space", Freeman (24 November – 1 December 1920); reprinted in Lewis Jacobs, ed., Introduction to the Art of the Movies (New York: Noonday Press, 1960), pp. 76–85.

- ^ "Anthony Vidler".

- ^ Anthony Vidler, Warped Space: Art, Architecture and Anxiety in Modern Culture (MIT Press, 2002), p. 104.; cf.J. P. Telotte, Animating Space: From Mickey to Wall-E. (University Press of Kentucky, 2010) pp. 223-224.

- ^ See Oskar Levy "Der Fall Herman George Scheffauer", in: Das Tagebuch[Berlin], 1924, 5. Jahrgang, 1. Halbjahr, S. 11–17.

- ^ See "Expressionism for America". Scheffauer's work reviewed by Gorham Bockhaven Munson (1896–1969), in: New York Evening Post Literary Review, (August 2, 1924), p. 930.

- ^ "Herman George Scheffauer Photograph Album, ca. 1885-ca. 1925".

- ^ "The Morning Post" (October 7, 1927)

- ^ "Scheffauer's Abschiedsbrief", in: Hamburger Anzeiger (13 Oct 1927), p. 10.

- ^ "Trauerfeier für Herman George Scheffauer", Berliner Tageblatt (October 28, 1927), p. 3

- ^ "Herman George Scheffauer papers, 1893–1927".

External links

[edit]- Works by Herman George Scheffauer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Herman George Scheffauer at the Internet Archive

- Works by Herman George Scheffauer at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Online Books Page | Herman George Scheffauer

- Literature by and about Herman George Scheffauer in the German National Library catalogue

- The New Shylock on Great War Theatre

- 1876 births

- 1927 suicides

- 1927 deaths

- San Francisco Art Institute alumni

- Writers from San Francisco

- Poets from California

- American architects

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- American male poets

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American journalists

- American male journalists

- 20th-century American poets

- American science fiction writers

- 20th-century German writers

- 20th-century American translators

- English–German translators

- Suicides by sharp instrument in Germany

- Translators of Thomas Mann

- American people of German descent

- American expatriates in Germany

- 20th-century American male writers

- Murder–suicides in Germany

- American murderers