Hellraiser: Bloodline

| Hellraiser: Bloodline | |

|---|---|

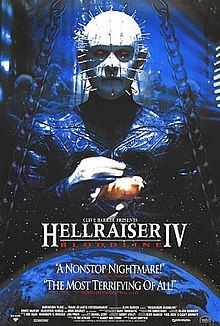

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Written by | Peter Atkins |

| Produced by | Nancy Rae Stone |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gerry Lively |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Daniel Licht |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[3] |

| Box office | $9.3 million[4] |

Hellraiser: Bloodline (also known as Hellraiser IV: Bloodline) is a 1996 American science fiction horror film and the fourth installment in the Hellraiser series, which serves as both a prequel and a sequel. Directed by Kevin Yagher and Joe Chappelle, the film stars Doug Bradley as Pinhead, reprising his role and now the only remaining original character and cast member. It also features Bruce Ramsay, Valentina Vargas, Kim Myers and Adam Scott in his first major film role. It was the last Hellraiser film to be released theatrically and the last to have any major official involvement with series creator Clive Barker until the 2022 reboot.

In the 18th century, a celebrated toymaker (Ramsay) is hired to create his greatest work, the Lament Configuration, not knowing that it will allow the summoning of the demonic Cenobites, including Pinhead (Bradley) and Angelique (Vargas). Hundreds of years in the future, the toymaker's descendant (also played by Ramsay), an engineer, has designed a space station that he believes can trap and destroy the Cenobites. Major themes include time, toys and game-playing, adultery and slavery.

The film had a troubled history and, after completing the film, original director Yagher left the production when distributor Miramax demanded new scenes be shot. It was subsequently completed by Chappelle. The new scenes and re-shoots changed several characters' relationships, gave the film a happy ending, introduced Pinhead earlier, and cut 25 minutes. Yagher felt the changes diverged too strongly from his vision and was granted the Alan Smithee pseudonym, an alias used by directors who want to go uncredited. Miramax released it in the United States on March 8, where it grossed $9 million. It was not screened for critics and received negative reviews.

Plot

[edit]In 2127, Dr. Paul Merchant, an engineer, seals himself in a room aboard The Minos, a space station that he designed. As armed guards attempt to break through the door, Merchant manipulates a robot into solving the Lament Configuration, destroying the robot in the process. The guards break through the door and apprehend Merchant, who agrees to explain his motivations to their leader, Rimmer.

The film flashes back to Paris, France, 1796. Dr. Merchant's ancestor, Phillip LeMarchand, a French toymaker, makes the Lament Configuration on commission from the libertine aristocrat Duc de L'Isle. Unbeknownst to LeMarchand, L'Isle's specifications for the box make it a portal to Hell. Upon delivering the box to L'Isle, LeMarchand watches as he and his assistant Jacques sacrifice a peasant girl and use her flayed-off skin to summon a demon, Angelique, through the box. LeMarchand runs home in terror, where he begins working on blueprints for a second box which will neutralize the effects of the first. Returning to L'Isle's mansion to steal the box, LeMarchand discovers that Jacques has killed L'Isle and taken control over Angelique, who agrees to be his slave so long as he does not impede the wishes of Hell. The pair kill LeMarchand, and Jacques informs him that his bloodline is now cursed for helping to open a portal to Hell.

In 1996, LeMarchand's descendant, John Merchant, has built a skyscraper in Manhattan that resembles the Lament Configuration. Seeing an article on the building in a magazine, Angelique asks Jacques to take her to the United States so that she can confront him. When Jacques denies her request, Angelique kills him, as Merchant poses a threat to Hell. Angelique travels to the United States, where she fails to seduce Merchant. Discovering the Lament Configuration in the building's foundation, Angelique tricks a security guard into solving it, which summons Pinhead. The two immediately clash, as Pinhead represents a shift in the ideologies of Hell, which she left behind two hundred years ago: while Angelique believes in corrupting people through temptation, Pinhead is fanatically devoted to pain and suffering. Despite their conflicting views, the pair forge an uneasy alliance to kill Merchant before he can complete the Elysium Configuration, an anti-Lament Configuration that creates perpetual light and would serve to permanently close all gateways to Hell.

Angelique and Pinhead initially collaborate to corrupt Merchant, but Pinhead grows tired of Angelique's seductive techniques and threatens to kill Merchant's wife and child. Having grown accustomed to a decadent life on Earth, Angelique wants no part of Hell's new fanatical austerity, and she intends to force Merchant to activate the Elysium Configuration and destroy Hell, thus freeing her from its imperatives. However, Merchant's flawed prototype fails. Pinhead kills Merchant, but his wife opens Angelique's Lament Configuration, sending Pinhead and Angelique back to Hell.

In 2127, Rimmer disbelieves Dr. Merchant's story and has him locked away. Pinhead and his followers – now including an enslaved Angelique – have already been freed after Merchant opened the box. Upon learning of Dr. Merchant's intentions, they kill the entire crew of the ship, save for Rimmer and Dr. Merchant, who escape. Dr. Merchant reveals that the Minos is, in fact, the final, perfected form of the Elysium Configuration, and that by activating it, he can kill Pinhead and permanently seal the gateway to Hell.

Dr. Merchant distracts Pinhead with a hologram while he boards an escape pod with Rimmer. Once clear of the station, he activates the Elysium Configuration. A series of powerful lasers and mirrors create a field of perpetual light, while the station transforms and folds around the light to create a massive box. The light is trapped within the box, killing Pinhead and his followers, thus ending Pinhead's existence, this time, permanently.

Cast

[edit]- Doug Bradley as Pinhead. In the shooting script, Pinhead had a violently antagonistic relationship with Angelique. This was softened during editing and pick-ups, and a hinted sexual attraction between them was introduced.[5]

- Bruce Ramsay as Philippe "Toymaker" LeMarchand / John Merchant / Dr. Paul Merchant. Ramsay called Philippe an ambitious but good man who is seduced by Angelique's power. He described John as more self-aware and mature; Paul, he said, is weathered.[6]

- Valentina Vargas as Angelique / Peasant Girl. Vargas said she was reluctant to take the role because of nightmares about Pinhead, but she soon became interested in exploring her character's seductive and evil nature.[7] Originally a demon summoned through black magic who commissions the Lament Configuration, her origin was changed to be dependent on the box.[8]

- Kim Myers as Bobbi Merchant. Bobbi was written to mirror Larry from the first film, both of whom suspect their spouses of infidelity.[7]

- Adam Scott as Jacques, de L'Isle's assistant. Jacques initially had a smaller role, but he was rewritten and expanded upon when Angelique's origin changed.[9]

- Christine Harnos as Rimmer. Originally male, Rimmer was rewritten in a later draft after several female characters were streamlined out, including a descendant of Kirsty Cotton who would serve as Paul's love interest.[10]

- Charlotte Chatton as Genevieve LeMarchand. In the script, Genevieve is also depicted as more suspicious of her husband, whom she suspects to be having an affair. This was mostly removed during editing.[11]

- Mickey Cottrell as Duc de L'Isle. In the script, de L'Isle had a larger part, but some of his scenes were given to Jacques when Angelique's origin changed.[9] He is modeled after the Marquis de Sade and Gilles de Rais.[12]

- Jody St. Michael as Chatterer Beast, a Cenobite. The script describes it as pieced together from the remains of a dog and a man after a car accident.[10] St. Michael played the Chatter Beast as an animal.[13]

- Courtland Mead as Jack Merchant

- Mark and Michael Polish as Siamese Twins[14]

Production

[edit]Pre-production

[edit]Clive Barker, acting as executive producer, wanted a fresh turn for the series after two sequels to his original 1987 film. The initial premise for the film, a shape-changing structure used to trap Pinhead, was inspired by the ending of Hellraiser III, which featured a building whose architecture resembled the Lament Configuration. Barker suggested a three-part film set in different time periods, and Peter Atkins added the LeMarchand storyline, going back to Barker's novella. Atkins had previously written Hellraiser II and co-written Hellraiser III. Atkins and Barker pitched the idea to Miramax, who greenlit it without requiring an outline.[15]

In The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy, author Paul Kane described the screenplay as ambitious and "one of the best of the Hellraiser sequels".[3] This screenplay featured a linear timeline, more special effects, and violent confrontations between Pinhead and Angelique. When Miramax was unwilling to provide a budget to realize these scenes, the film was scaled back. Stuart Gordon, known for his low-budget horror films, was approached to direct but backed out after artistic disagreements. Special effects technician Kevin Yagher was subsequently hired after his cost-saving directing work on Tales from the Crypt for Joel Silver. Yagher was initially hesitant about taking the job, as he did not want to do a retread of the previous installments of the series. However, he was impressed with the script and became enthusiastic after Barker described his vision for the film.[16]

Doug Bradley, who had played Pinhead in all the previous films, joined the cast first. Bradley agreed the film should focus more on the other characters, and several lesser-known actors joined in major roles, including Canadian Bruce Ramsay and Chilean Valentina Vargas. As the script was scaled back once again to save money, the number of characters was reduced, and several were rewritten to have simpler motivations and origins. Gary J. Tunnicliffe of Image Animation, who had previously worked on Hellraiser III, was recruited to perform special effects. Tunnicliffe was worried that Yagher would want to perform the effects himself, but Yagher wanted to collaborate with Image Animation and believed their experience with prior films in the series would be valuable. Yagher himself only contributed to the Chatter Beast. For Angelique's appearance, Tunnicliffe was inspired by Morticia Addams and Sister Act, converting the imagery of a nun's habit to flayed skin. In Hellraiser III, Bradley's make-up as Pinhead had changed to make it easier to apply and take off at the cost of increased discomfort. Tunnicliffe reverted to the old make-up, which he believed looked better.[17]

Filming and post-production

[edit]Filming began in Los Angeles in August 1994. Locations included the I. Magnin Building, which was rumored to be haunted, and an abandoned factory, which was converted into the space station. Problems began early and continued throughout production. Bradley called it "the shoot from hell".[5] Gerry Lively, who had shot Hellraiser III, replaced the original cinematographer, the assistant director was called away on an emergency, several people suffered from illnesses, and Bradley said the art department and camera crew were all dismissed within the first week. Despite the issues, Hellraiser IV was completed on time and within its budget. The initial cut of the film, shown to studio executives in early 1995, was 110 minutes.[18]

Miramax's reaction was negative, however, and they demanded that Pinhead receive a more prominent role and appear earlier. Atkins said they knew about the script but possibly panicked when they saw the reality. Miramax's demands required rewrites; Pinhead was inserted into the opening of the film, which was changed so that the 22nd century Paul Merchant narrates his ancestors' story, and a happy ending was added. Yagher, coming off the difficult shoot, declined to direct the new scenes and left the production, citing a lack of time and energy. Though he was not necessarily opposed to Miramax's suggested changes, Yagher said he also did not want to see the film slowly morph into a different product after spending so much effort on it.[18]

Director Joe Chappelle was brought in to complete the film.[19] Atkins wrote three new scenes, and, when he became unavailable, Barker recommended Rand Ravich, who had previously worked on Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh. New footage was shot in April and May 1995. Bradley said they consisted of entirely new material and were not truly re-shoots. Angelique's origin and relationships with Pinhead and the LeMarchand line were changed. Many scenes were removed during editing, especially from the LeMarchand storyline. Angelique and Pinhead originally had a more violent and adversarial relationship; Angelique represented an older, more chaotic version of Hell that favors drawn-out temptation, and Pinhead represented an ascetic, results-based order that takes over. The theatrical cut makes this more ambiguous and replaces some of their hostility with sexual tension. The final cut was 85 minutes long. When Yagher saw the finished film, he felt it strayed too far from his original vision and had his name removed from the credits, using the DGA pseudonym Alan Smithee.[20]

Themes

[edit]This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (December 2016) |

Kane identifies several themes in the film. The first, time, is evident in the film's non-linear narrative, which takes place in the past, present, and future. Kane compares the flashbacks told from the future with time travel stories. Though Paul does not travel through time, he succeeds in his task, Kane writes, because of his knowledge of the past, including his ancestors' plans and their failings. The characters frequently reference time in dialog, and clocks are a common background element, especially in Phillip's toy shop. In the space station, a countdown announces the time until the Elysium Configuration will kill Pinhead and his fellow Cenobites. Before he dies, Pinhead announces, "I am forever!"[21]

Toys and game-playing are a common theme in the film series, all of which feature the Lament Configuration, a mystical puzzle box created by a toymaker. Kane identifies these themes as "much more blatant" in Bloodline. In the original shooting script, demonic gamblers served Angelique. She plays sexual games with her victims, and Pinhead toys with mortals for amusement. Kane draws parallels to video games when John uses a computer to design the Elysium Configuration, and Kane compares the space station scenes to a shoot 'em up game in which Paul insists only he can win the endgame. Pinhead makes many references to game-playing, including when he kills John, and John's wife, Bobbi, references game-playing when she sends Pinhead back to Hell.[22]

Kane identifies sex, death, and adultery as frequently intertwined, though he says this is somewhat weakened in the theatrical cut. Angelique tempts the LeMarchand bloodline, and adultery results in their death. Due to cuts made during editing, Kane says this is most evident in Angelique's relationship with John; in the shooting script, Phillip's obsession with Angelique and the Lament Configuration more explicitly mirrored that of a marital affair. Kane writes that Paul avoids death by ignoring relationships and is rewarded with a relationship once he redeems his bloodline. Jacques orders Angelique to kill Phillip out of jealousy, and it is this same jealousy that later causes his death at Angelique's hands.[23]

According to Kane, many of the characters' relationships are based on slavery and bondage. Angelique is a slave to de L'Isle, then Jacques. When she rebels against the new austerity in Hell, she comes into conflict with Pinhead, who eventually puts her under his control. Pinhead himself is a slave to the will of Hell, though Kane says he exercises more independence than Angelique. The LeMarchand bloodline are slaves to the Lament Configuration; John, and, to a lesser extent, Phillip are also slaves to their obsession with Angelique. Mirror images feature prominently in the film, including the twin cenobite and literal mirrors that Angelique and Paul use. In Kane's analysis, Paul not only mirrors his ancestors but also Pinhead, whom he emulates to become stronger. Kane describes how darkness and light also show up in the film, sometimes literally, as when light kills Pinhead, and sometimes metaphorically, as when Angelique and Pinhead show elements of their underlying humanity.[24]

Soundtrack

[edit]The score was composed by Daniel Licht and was released on March 19, 1996.[25] Kane wrote of it: "The whole score is powerful, blending unconventional instrumentation occasionally augmented by a chorus".[26] Kane highlighted the chase sequence music in the Chatter Beast's scenes.[26]

Release

[edit]Bloodline was not screened for critics.[27] It was released on March 8, 1996, in the United States and Canada, where it grossed $4.5 million in its opening weekend and came in fifth place. At the end of its U.S. run, it grossed $9.3 million.[4] Bloodline was the final Hellraiser film to receive a theatrical release,[28] though it was released direct-to-video in the UK.[26] Following the film's release, questions of a sequel immediately rose. Atkins said he was uninterested in exploring more Hellraiser stories, as he could not see anywhere for the series to go creatively, but he recognized Miramax had a financial interest in keeping the series alive. Bradley said he was open to reprising his role, but Barker's reaction was more negative.[29]

Home media

[edit]Hellraiser: Inferno followed in October 2000, going direct-to-video.[30] Dimension released Bloodline on VHS and DVD in 1996[31] and 2001,[32] and Echo Bridge Home Entertainment released it on Blu-ray for the first time in 2011.[33][34]

Reception

[edit]Bloodline received negative reviews on release. Kane wrote that "reviewers lined up to criticize and condemn the movie".[35] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 24% of 17 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 4.1/10.[36] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 21 out of 100, based on 10 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable" reviews.[37]

Variety called it "a pointless mess" without a likable protagonist. The reviewer further criticized the acting and said the grotesque special effects have become tiresome since the first film, except for the space-based effects.[38] Also criticizing the special effects, Richard Harrington wrote in The Washington Post that they are "decidedly gross but not particularly frightening".[39] Harrington said the film would need a "a far bigger budget and some real input from horrormeister Clive Barker" to realize its aspirations.[39] Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote that the film is "incoherent and (except for Mr. Bradley's Pinhead) wretchedly acted".[40] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote that if Barker himself had rewritten and directed the film, it might have worked; however, the writing is convoluted, and the film's atmosphere is "more repellent than intriguing".[27] Thomas praised the acting of Bradley, Cottrell, and Ramsay but called the rest of the cast "mediocre".[27] In rating the film one star out of four, TV Guide called it the most ambitious but worst of the film series.[41]

The film also received retrospective reviews. Reviewing the film on Blu-ray for Dread Central, Matt Serafini rated it 2.5/5 stars and wrote that the film was not respected by producers, ultimately causing it to become "a half-baked compromise" that does not live up to its interesting premise, ultimately degenerating into a generic slasher film in the climax. Serafini identified Vargas' role as wasted and said the thin material limits the supporting cast.[28] Also reviewing the film of video, Entertainment Weekly's J. R. Taylor gave it a letter grade of "B" and called it "actually rather interesting" despite its incoherent moments, which are made more tolerable when watched on DVD.[31] After watching a marathon of Hellraiser films, religion scholar Douglas E. Cowan called Bloodline his favorite. While acknowledging fan criticism, he identified the film's expanded mythology and religious themes as making it more interesting than previous installments. Cowan describes Pinhead's dismissive rejection of God's will as possibly symbolic of modern society's views on religion.[42] Katie Rife, who also watched the series in a marathon for a retrospective at The A.V. Club, called it "an entertaining mess". Rife wrote that fans passionately defend the film, and, despite its flaws, Bloodline never becomes boring.[43]

Sequel

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Joe Chappelle completed uncredited reshoots on the film without Yagher's involvement. Yagher additionally disavowed the theatrical film and requested to be credited as Alan Smithee.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Hellraiser: Bloodline". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ^ "Hellraiser Iv: Bloodline (1996)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 136.

- ^ a b "Hellraiser 4: Bloodline". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 141.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 137–138.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 133, 149.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 151.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 135.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 149.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 154.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 147.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 136–137.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 138–139.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 140–141.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 141-142.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 144–145.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 145–148.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 148–150.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 151–154.

- ^ "Hellraiser 4: Bloodline (Original Soundtrack) - Daniel Licht". AllMusic. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ^ a b c Kane 2013, p. 143.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Kevin (1996-03-11). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Hellraiser: Bloodline' Has More Diabolical Designs". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ a b Serafini, Matt (2011-05-14). "Hellraiser: Bloodline (Blu-ray)". Dread Central. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 158.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 166.

- ^ a b Taylor, J. R. (1996-11-22). "Hellraiser: Bloodline". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ Naugle, Patrick (2001-06-29). "Hellraiser: Bloodline". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ "Hellraiser: Bloodline". IGN. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ "Hellraiser: Bloodline Blu-ray (Hellraiser IV)".

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 157.

- ^ "Hellraiser: Bloodline". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ "Hellraiser: Bloodline". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Review: 'Hellraiser: Bloodline'". Variety. 1996-03-10. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ a b Harrington, Richard (1996-03-09). "'Hellraiser': Dawn of a Dud". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2016-10-02 – via Highbeam Research.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (1996-03-09). "FILM REVIEW;Where Tempers And Heads Tend to Fly". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ "Hellraiser: Bloodline". TV Guide. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ Cowan, Douglas E. (2012). Clark, Terry Ray; Clanton, Dan W. (eds.). Understanding Religion and Popular Culture. Routledge. pp. 56–58. ISBN 9781136316043.

- ^ Rife, Katie (2014-10-30). "Watching all 9 Hellraiser movies is an exercise in masochism". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

Bibliography

[edit]External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- 1996 horror films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s science fiction horror films

- American science fiction horror films

- American sequel films

- American space adventure films

- American splatter films

- American supernatural horror films

- Dimension Films films

- Films based on works by Clive Barker

- Films credited to Alan Smithee

- Films directed by Joe Chappelle

- Films directed by Kevin Yagher

- Films scored by Daniel Licht

- Films set in 1796

- Films set in 1996

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in the 2120s

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in Paris

- Films shot in Toronto

- Hellraiser films

- Miramax films

- American religious horror films

- 1996 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction horror films