Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth

| Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth | |

|---|---|

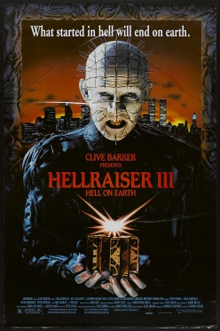

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Hickox |

| Screenplay by | Peter Atkins |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Characters by Clive Barker |

| Produced by | Lawrence Mortorff |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gerry Lively |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Randy Miller |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Films[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes[2] |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Box office | $12.5 million (US)[4] |

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth is a 1992 American supernatural horror film and the third installment in the Hellraiser film series. It was directed by Anthony Hickox and stars Terry Farrell, Paula Marshall, Kevin Bernhardt, and Doug Bradley. Ashley Laurence, who starred in the previous two films, reprises her role as Kirsty Cotton in a cameo appearance.

Following the events of Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), in which the demon Pinhead (Bradley) is imprisoned in a statue, he resurrects himself by absorbing the life force of unlucky humans. After converting several power-hungry youths (Marshall and Bernhardt) into new Cenobites, Pinhead goes on a rampage, opposed by a reporter (Farrell) and the spiritual manifestation of his good half (also Bradley).

Series creator Clive Barker reprised his role as executive producer, though he was largely uninvolved until post-production. It was the first Hellraiser film to be filmed outside the United Kingdom and the first release by Dimension Films. The film's reception on release was better than the previous film, and it grossed $12.5 million in the US.

In 1996, it was followed by Hellraiser: Bloodline, which was the last film in the series to be theatrically released.

Plot

[edit]The revelation of his own former humanity causes Pinhead,[a] a demon called a Cenobite, to be split into two entities: his former self, World War I British Army Captain Elliot Spencer, and a manifestation of Spencer's id, which takes on the form of Pinhead. While Spencer ends up in limbo, Pinhead is trapped, along with the puzzle box, among the writhing figures and distorted faces etched into the surface of an intricately carved pillar — the Pillar of Souls.

J. P. Monroe, the womanizing owner of a popular New York nightclub called The Boiler Room, buys the pillar. An ambitious young television reporter, Joanne "Joey" Summerskill, sees hooked chains embedded in a teenage clubgoer in a hospital emergency room. They come to life and tear the clubgoer to pieces. A young homeless woman, Terri, who came in with the clubgoer, explains that the chains sprang from the puzzle box, which she pried from the pillar. Terri gives the puzzle box to Joey. While investigating the box's background with the help of her cameraman, "Doc", Joey invites Terri to stay with her. Joey uncovers a video tape from one of Pinhead's former victims, Kirsty Cotton, that explains the puzzle box is the only means of returning Pinhead to Hell. Pinhead remains dormant until Monroe has rough sex with a clubgoer, Sandy. Afterward, hooked chains drag Sandy to the pillar and Pinhead absorbs her body. Pinhead points out that they have both used Sandy for their own purposes. Although initially horrified, Monroe agrees to bring Pinhead more club members so he can feed on them and be freed. In return, Pinhead promises Monroe power and unnatural delights.

Joey has recurring nightmares about how she presumes her father died in Vietnam. During one such dream, Spencer contacts Joey. He explains that his experiences in World War I caused him to lose faith in humanity, and he sought out the forbidden pleasures promised by the puzzle box. Spencer tells her that without his humanity to act as a balancing influence, Pinhead is completely evil and will indiscriminately wreak havoc on Earth for his own pleasure, in violation of the Cenobite's laws. To defeat him, Joey must reunite Spencer's spirit with Pinhead and use the puzzle box to return him to Hell. A misunderstanding leads Terri to believe that Joey has abandoned her, and she returns to the arms of her ex-boyfriend, Monroe. Monroe attempts to feed her to Pinhead, but she overpowers him. Before she can flee, Pinhead talks her into feeding Monroe to him, promising to turn her into a demon in return. Now free, Pinhead massacres the club's patrons. Hearing the news reports, Joey goes to the club to investigate.

Pinhead orders Joey to give him the box, but she escapes him. Pinhead resurrects several of his victims as demonic Cenobites, including Terri, Monroe, the barman, the DJ, and "Doc", who also left to investigate the club. Joey flees through the quiet streets, pursued by the new Cenobites. The Cenobites kill local police as Joey enters a church and begs the priest to help her. Lacking in faith that demons could exist, the priest is appalled by the appearance of Pinhead. Pinhead defiles the church and almost kills the priest until Joey regains his attention to the puzzle box she holds and gets him to chase her. The Cenobites trap Joey on a construction site and prepare to torture her. She solves the puzzle box, and they are sent to Hell. The box transports Joey into limbo, where she comes face to face with an apparition who appears to be her dead father. The apparition tells Joey to give him the puzzle box, only to be revealed as Pinhead in disguise.

Pinhead ensnares her in machinery and prepares to transform her into a Cenobite. Spencer's limbo-bound spirit confronts Pinhead and forcibly fuses himself into Pinhead. Joey breaks free and uses the puzzle box, which has transformed into a dagger, to stab Pinhead through the heart, sending him back to Hell. With Pinhead's humanity restored, the box returns Joey to Earth. She buries it in a pool of concrete at the construction site. Later, the finished product of the same site is revealed: a building whose interior design is identical to the box.

Cast

[edit]- Terry Farrell as Joanne "Joey" Summerskill

- Doug Bradley as Pinhead / Captain Elliott Spencer

- Paula Marshall as Terri / Dreamer Cenobite / Skinless Sandy

- Kevin Bernhardt as J. P. Monroe / Pistonhead Cenobite

- Ken Carpenter as Daniel "Doc" Fisher / Camerahead Cenobite

- Peter Atkins as Rick "The Bar Man" / Barbie Cenobite

- Aimée Leigh as Sandy

- Brent Bolthouse as "The DJ" Cenobite

- Eric Willhelm as CD Cenobite

- Robert Hammond as Chatterer Cenobite

- Clayton Hill as the Priest

- Peter G. Boynton as Mr. Summerskill

- Lawrence Kuppin as the Derelict

- Sharon Percival as Brittany Virtue

- Philip Hyland as Brad

- David Young as Bill

- Peter Boynton as Joey's Father

Heavy metal band Armored Saint cameo as themselves, performing their song "Hanging Judge" at The Boiler Room nightclub.[5] Actress Ashley Laurence, who played the female lead character Kirsty Cotton in the previous two films, has a cameo appearance via an in-universe videotape.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]New World Pictures and Film Futures, a production company owned by Clive Barker and Chris Figg, held meetings about a third Hellraiser film before Hellbound was released.[6] Barker had originally intended for the Hellraiser sequels to focus on Clare Higgins' character Julia, but Higgins declined to reprise her role in a third film, and her character was killed off in later drafts of Hellbound.[7] Other ideas included a story set in ancient Egypt, a followup to Hellbound in which Pinhead attempted to resurrect himself, and a building that functioned as a Lament Configuration. Aspects from the latter two would make it into the final script.[6]

During these talks, 20th Century Fox demanded extensive cuts to Barker's latest film, Nightbreed, an adaptation of his novella Cabal. Following a misleading marketing campaign from Fox that promoted it as a slasher film, Nightbreed underperformed at the box office and caused Film Futures to go out of business. With New World's own bankruptcy troubles, Hellraiser III went into development hell. Former New World executives, including Lawrence Kuppin, established Trans-Atlantic Pictures, and the rights were transferred to them. Following disagreements with Trans-Atlantic, Barker had no official involvement in the project until much later, during post-production; he said the studio balked at his fee, as they wanted a "cheap and nasty" film.[6]

Tony Randel, who directed Hellbound, co-wrote the story with Peter Atkins. Atkins completed the first draft of the screenplay in 1991. Many major elements remain unchanged from the shooting script, but the Barbie and CD Cenobites do not exist.[8] The end of the screenplay has Pinhead and Elliott merge into one being, but, following this, Joey makes a deal with him to be his willing bride in return for a successful life. Subsequent rewrites introduced the CD and Barbie Cenobites, Pinhead's deception as Joey's father, and a happier ending. The setting was made unambiguously American, ending the first two films' tradition of mixing British and American elements.[9]

Pre-production

[edit]Randel was attached to direct, but the producers removed him after they became worried that his vision for the film was too bleak.[8] Anthony Hickox replaced Randel after a mutual friend, whom Hickox had cast in Waxwork II: Lost in Time, suggested him. Barker, who disliked Hickox's prior work, believed him a poor fit for the Hellraiser series, as Hickox was known for horror comedy films. When Hickox met with him, Barker stressed that he expected Hickox to take the material seriously. Hickox, a fan of the series, agreed and used the first two films as a guide for the proper tone.[10]

Only two actors returned from the prior films: Doug Bradley as the Cenobite Pinhead and, in a cameo, Ashley Laurence as Kirsty. Hickox said he found the casting process for a Hellraiser film both exciting and frightening. The first to be cast was Terry Farrell, who was returning to a career in acting after a break. Hickox had previously sought her for a role in Waxwork II, but, when that became impossible because of a scheduling clash, he promised to cast her in his next project. Kevin Bernhardt, who had appeared as a series regular on General Hospital, was cast as J. P. Munroe. The role of Monroe's girlfriend, Terri, went to Paula Marshall, who Hickox said was a critical casting choice, as the film rested on the performances of Marshall, Ferrell, and Bradley.[11]

For Joey's cameraman, Ken Carpenter, an actor friend of studio executive Kuppin, was cast, as he had the look they wanted: practical and hard-working. Atkins himself took the role of the barman and the subsequent Barbie Cenobite, and several other crew members, including Kuppin and producer Lawrence Mortorff, took cameo roles. Smaller roles were filled with friends-of-friends, local actors, and people who had appeared in prior genre films, including Hickox's Waxwork series.[12]

Most of the crew were new to the series, too. Hickox brought many crew members from his previous films, including cinematographer Gerry Lively, who worked with Hickox on Waxwork II. Bob Keen from special effects company Image Animation was one of the few returning crew members from previous Hellraiser films. Keen had also previously worked on Nightbreed and the Waxwork films. Gary J. Tunnicliffe, who would become a writer and director in later Hellraiser films, joined the film's make-up crew and created the Lament Configuration boxes. Paul Jones replaced Geoff Portass as make-up coordinator.[13]

Filming

[edit]Hellraiser III was the first film in the series shot in the United States.[14] Laurence's scene, a recorded interview in which Kirsty explains the series' mythology, was shot separately prior to the rest of the film.[11] Principal photography began in late 1991 in Greensboro, North Carolina, which stood in for New York City. J. P.'s club was set in a furniture factory in neighboring High Point.[15] The interiors were shot at Carolina Atlantic Studios in High Point.[16]

Trans-Atlantic gave Hickox six weeks to shoot the film. Hickox had previously established a very fast shooting schedule that used long hours, which meant the Hellraiser III cast had to adjust to his unorthodox style and the studio's demands. Bradley said that he worked for seventeen hours straight one day, and the large number of scenes shot daily meant they had little time to perfect them. Hickox's preference for in-camera editing sped up production but limited the actors' view of how the completed film would look. They instead had to depend on storyboards. Unlike previous Hellraiser films, the stages used were all very close to each other and shared a single sound stage, which made shooting simultaneously with multiple crews difficult.[15]

Though Bradley said he enjoyed the production and working with Hickox,[17] he experienced discomfort in some of his scenes. Early on, Bradley had to act from within the uncomfortable Pillar of Souls prop, where Pinhead is trapped. This restricted Bradley's acting to just his face and voice. Bradley also said that the make-up from Hellraiser III was his least favorite. Jones had changed Pinhead's make-up to make it faster to apply and remove, but this had the side-effect of making it more uncomfortable to wear. However, Bradley was able to find an optician that allowed him to wear a prescription version of Pinhead's black lenses, allowing him to stay in-character for much longer periods.[18]

During the sex scene between Aimée Leigh and Burnhardt, Leigh protested at having to appear topless. This was resolved by having Burnhardt place his hands on her breasts, obscuring them.[19] The cast and crew reportedly got along well, and during an on-set visit by Fangoria magazine, the only complaint reported was that Marshall found her outfit too light to shoot during a cold winter night.[17] The scene where Elliott and Pinhead confront each other was difficult to shoot, necessitating a stand-in for Pinhead. Bradley remarked that he felt "jealously protective" of the character when he saw his stand-in, as this was the first time anyone else had ever appeared in-character as Pinhead on a Hellraiser set.[18]

The biggest issue was the Black Mass scene, which caused controversy in socially-conservative North Carolina. Hickox had been refused permission to shoot in a real church, so he used a matte painting as a background to the altar. When the crew complained of sacrilege, Hickox told them it was no different than the countless Hammer horror films in which Christopher Lee, as Dracula, rampaged in churches. Besides that, Hickox reported only a healthy rivalry between Marshall and Farrell, which he welcomed, as it encouraged them to up the ante in their shared scenes.[17]

Special effects

[edit]Keen's effects crew of Hellraiser III included coordinator Paul Jones; supervisors Steve Painter, Mark Coulier, and Bob's brother Dave; head sculptor Paul Catlin, and mechanical effects coordinator Ray Bivins.[20]

For Hellraiser III, Keen used a two-piece prosthetic where small plates in the makeup stood up the pins.[21] It took only three hours to apply the make-up,[20] around two hours less than it took to apply the six-to-seven-piece Pinhead makeup in the past two films.[22] A "motor with an off-centered cam" was also built into the right hand side of J.P.'s makeup, where moved around the head and pushed a piston to the left hand side.[20] The actors for both Barbie and CD Head wore prosthetic mask for their roles, with a dummy replication for both characters for shots showing when they used their weapons.[20]

Barbie's transformation was done through "reverse shots", where silver-sprayed barbed wire was wrapped around by different strings in each shot.[20] Real barbed wire was used on dummies, while the fake barbed wire was used on the human actors.[20] Producing Barbie's flamethrowers involved putting gas and a 40-foot flamethrower in a fiberglass head; the gas would build up inside a fake torso before fire blasted through the top head.[20]

Post-production

[edit]Kuppin suggested that Hickox use the non-linear editing system Ediflex, which was made by a company he owned. This was quickly abandoned after the software turned out to be too time-consuming. Miramax soon became interested in distributing the film in the US, but what happened next is contentious. According to Hickox, Bob Weinstein loved the rough cut he saw and offered Hickox money for additional effects work and to redo the ending. This resulted in an early use of computer-generated imagery – the first in a horror film – to add several gory scenes.[23]

Barker disputes this account and says that Kuppin showed him a work print. Unimpressed, Barker declined an executive producer credit, criticizing the film's ending and low-budget effects work. After Miramax become involved, Barker says Weinstein asked for his honest evaluation of the film. Barker reiterated his criticisms, and, at Weinstein's urging, came in to fix the film. In Barker's account, he was the one responsible for Farrell's bondage scene, additional scenes of extended gore in the nightclub massacre, and the CGI when Leigh's character is skinned. Regardless of the extent of Barker's involvement in post-production, it was now enough for him to accept an executive producer credit, and the film was given a "Clive Barker Presents" banner. Additionally, Barker promoted the film alongside Candyman.[24]

Themes

[edit]Writing in The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy, author Paul Kane identifies several themes in the film. The first, the horrors of war, Kane identifies as the strongest and most pervasive. Hellraiser III pays homage to war films like Apocalypse Now, Platoon, and Born on the Fourth of July. Kane says both Joey and Elliott are depicted as seeking answers following traumatic experiences with war. Joey wants to understand her father's death in Vietnam, and Elliott searches for meaning after losing his faith in both God and mankind. After Elliott's transformation into Pinhead, he commands Hell's forces, and later is shown directing the newly created Cenobites. Hickox said this is a direct allusion to Elliott's war experiences.[25]

Kane identifies dreams as another common theme, often in terms of how they relate to desire. According to Kane, Joey's nightmares reflect her frustrated ambition to be recognized in her career and beat the glass ceiling. Though her dreams of getting the story of her life come true, she is left no better off, as there is no evidence. Likewise, Pinhead appeals to J. P.'s and Terri's dreams, promising to make their ambitions come true. For Terri, this is more literal, as she desires the ability to dream. Kane says that although the film never explicitly states this, it is clear that Elliott wishes to regain his humanity; more immediately, he seeks to control Pinhead, who, in turn, desires unrestrained freedom.[26]

In Kane's analysis, technology and, specifically, communication devices figure prominently: unplugged radios and televisions transmit warnings from Elliott, Kirsty's warning comes in the form of a videotape, and Joey works in the television industry. The transformed Cenobites are fused with technology, which Kane compares to Tetsuo: The Iron Man.[27] These transformations also illustrate another theme: duality. Many of the characters have an alter ego, such as Elliott and Pinhead. Kane says that although Joey does not have a physical alter ego, her dream-self regresses to that of a young child similar to Lewis Carroll's Alice.[28]

Kane says many of the characters and their relationships in Hellraiser III match to those of the first two films. Like Kirsty, Joey has lost her father, and she finds a new father figure in Elliott. Kane identifies Elliott as a vaguely-hinted-at love interest for her, as he shares a psychic intimacy with her that no living man can. Joey and Terri initially have a relationship similar to Kirsty and Tiffany in Hellbound, then an antagonistic one similar to Kirsty and Julia in Hellraiser. According to Kane, both J. P. and, to some extent, Pinhead mirror Frank's insatiable lust. Kane describes the Cenobites as reflections of the ones from the first two films.[29]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film features a heavy metal-rock soundtrack. Initially, the score was also meant to be rock music, but this went over poorly in test screenings. Randy Miller was brought in to compose a more traditional, orchestral score within three weeks. Given a restricted budget, the Mosfilm State Orchestra and Choir in Russia was chosen to perform the score. The Russian orchestra, unaccustomed to Hollywood demands, felt they did not have enough time to rehearse, but Miller said they eventually welcomed the challenge.[14] Miller incorporated Christopher Young's themes from the previous films.

Barker directed the Motörhead video for "Hellraiser", featuring Lemmy and Pinhead playing a game of cards and varied clips of the film.[30]

- Motörhead – "Hellraiser"

- Ten Inch Men – "Go with Me"

- Material Issue – "What Girls Want"

- Electric Love Hogs – "I Feel Like Steve"

- Armored Saint – "Hanging Judge"

- Triumph – "Troublemaker"

- KMFDM – "Ooh La La"

- Tin Machine – "Baby Universal"

- Soup Dragons – "Divine Thing"

- House of Lords – "Down, Down, Down"

- Motörhead – "Hell on Earth"

- Chainsaw Kittens – "Waltzing with a Jaguar"

Armored Saint, who contributed to the song "Hanging Judge", make a brief appearance in the film. The single "Hellraiser", which Motörhead's Lemmy Kilmister had helped write, was originally recorded by Ozzy Osbourne on No More Tears.[31][32]

Release

[edit]Hellraiser III required several cuts before the Motion Picture Association of America was willing to grant it an "R" rating. Barker ascribed their increased scrutiny to his outspokenness on social issues and the growing popularity of the Hellraiser films, which he said they initially saw as too obscure to care about.[33] It premiered at the Dylan Dog Horror Fest in May 1992.[34] Miramax released the film theatrically in the United States on September 11 the same year.[4] It was the first Dimension film to be distributed by Miramax.[1] The film debuted in third place, grossing $3.2 million, which the Los Angeles Times characterized as "tepid business".[35] The film grossed $12.5 million in 898 theaters across the United States and Canada,[4] making it the second-highest-grossing film in the Hellraiser series.[36] It was released on home video in May 1993[37] via Paramount Pictures and debuted the next month on Billboard' video rental charts at #19, with the Los Angeles Times describing this as "very good business".[38] An R-rated version of the film was released on DVD in the US on August 8, 2006; it includes a documentary short about Barker's inspiration from 1992.[39]

Reception

[edit]On release, reviews of Hellraiser III were overall more positive than Hellbound. Kane attributes this to the film's more commercial aspirations than the previous two films.[34] Variety's review echoed this, calling it "highly commercial",[40] and Jack Yeovil of Empire said it is "a good horror sequel" that succeeds in its simple goal: to appeal to mainstream American teenagers.[41] Nigel Floyd of Time Out London called it "adult horror to die for".[42] Marc Savlov, film critic for The Austin Chronicle, instead called the film "about as traumatic as a de-clawed Cerebus".[43] In a retrospective review from 2006, Steve Barton of Dread Central called it "just plain goofy" and a low point in the series.[44] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 40% of 20 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 4.4/10.[45] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 50 out of 100, based on 12 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[46]

Writing for The Washington Post, Richard Harrington described the plot and themes as faithful to the previous films. Pinhead, he said, is "more ambitious, and more dangerous, than ever", and there is "never a dull moment".[47] Compared to the first film, which he dubbed "deliciously original", Savlov said Hellraiser III is a "tepid and wholly uninspired retread of various genre conventions".[43] Yeovil praised Atkins' script for its "surprisingly careful characterisations" and abandoning the "waffling metaphysics" of the previous film, but said that Pinhead remains "a sub-Freddy goon" and the film has been purged of some of Barker's perversity and ambiguity.[41] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated it a letter grade of C− and wrote that the film, though it has a provocative theme, is more oriented toward vulgar depictions of gore than "the thin line separating pleasure and pain".[48] Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote that the series' mythology had become too complex by this point for newcomers to understand despite its popularity with horror fans.[49] At the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas described the plot as "quite imaginative and even poignant" but said the violence numbs audiences looking for more than just gory special effects, unlike the first film.[50] Chicago Tribune critic Johanna Steinmetz said that Joey and Pinhead do not have chemistry, and their back stories fail to mesh with the rest of the plot.[51]

Commenting on the film's acting, Variety's review identified Farrell as a "strong heroine" and Bradley as "a commanding presence".[40] Harrington said it was "hardly a surprise that Bradley steals the film" and called Farrell "solid".[47] Maslin said that Pinhead's portrayal makes him of interest to "a more discerning audience", and the film "unfolds as intelligently as it can, under the circumstances".[49] Bradley was also highlighted by Thomas, who called him "a fine actor of much resonance"; Thomas wrote that none of the other cast members are as good, describing them as "callow".[50] In a retrospective of the entire series for The A.V. Club, Katie Rife wrote that "everyone is acting as hard as they possibly can", but the campy scenes make the more serious ones difficult to accept. She also criticized the dialogue as "rejected first drafts of a True Detective episode".[52]

Variety called the film "an effective combination of imaginative special effects with the strangeness of author Clive Barker's original conception".[40] In a pun on special effects supervisor Bob Keen' s name, Harrington called the effects "peachy Keen" and said Pinhead is Keen's masterpiece.[47] Maslin's review described the special effects as "commendable" for bringing sophistication and "helping to usher in the age of high-tech horror".[49] Thomas wrote that the effects are "too obviously synthetic to scare adults" but could be nightmarish for children.[50] Writing for the Deseret News, Chris Hicks said the film is "one of the most gruesome and unpleasant horror movies", enjoyable only by fans of splatter films.[53] Barton criticized the new Cenobites as "lame" and said the special effects have not aged well, now seeming to be "sickeningly amaturish". According to Barton, this makes the film "pretty tedious viewing".[44] Rife said the design of the new Cenobites bears "the distinct stamp of the early '90s".[52]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As depicted in Hellbound: Hellraiser II.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "HELLRAISER III - HELL ON EARTH (18)". British Board of Film Classification. September 23, 1992. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ "Hellraiser III Hell on Earth (1992)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "Has Barker done a book for kids?". The Baltimore Sun. September 29, 1992. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c Kane 2013, p. 95–98.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 59.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 100–101.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 101–104.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 105–106.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 106.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 107.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 107–108.

- ^ "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kane 2013, p. 110.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 108.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bacal 1992, p. 31.

- ^ Bacal 1992, p. 30–31.

- ^ Bacal 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 110–111.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 110–113.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 114–116.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 116–121.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 121–122.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 124–125.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 122–124.

- ^ Kane 2013, p. 113.

- ^ Foy, Scott (March 2, 2013). "B-Sides: Motorhead Raises Hell". Dread Central. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "Motorhead's Lemmy: 20 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. December 29, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (September 11, 1992). "Clive Barker and the Horror of It All". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Kane 2013, p. 130.

- ^ "Sneakers Races to the Top Spot". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ "Franchises: Hellraiser". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (May 14, 1993). "Cheer Up! 'Cheers' Lives via Mail Order". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (June 4, 1993). "National Video Rentals : An Impressive Premiere for 'River'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Weinberg, Scott (October 3, 2006). "Hellraiser 3: Hell on Earth". DVD Talk. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Hellraiser III – Hell on Earth". Variety. 1992. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Yeovil, Jack (January 2000). "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth Review". Empire. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Floyd, Nigel (September 10, 2012). "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". Time Out London. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Savlov, Marc (September 18, 1992). "Hellraiser III: Hell On Earth". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Barton, Steve (August 14, 2006). "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (DVD)". Dread Central. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c Harrington, Richard (September 11, 1992). "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Review/Film; High-Tech Horror and a Body Count to Match". The New York Times. September 12, 1992. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Kevin (September 14, 1992). "'Hellraiser III': Stylish, Grisly". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Steinmetz, Johanna (September 16, 1992). "Chastity Beats The Devil In 'Hellraiser Iii'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Rife, Katie (October 30, 2014). "Watching all 9 Hellraiser movies is an exercise in masochism". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Hicks, Chris (October 4, 1992). "Gory 'Hellraiser III' Is Hell To Sit Through". Deseret News. Retrieved August 11, 2018.[dead link]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bacal, Simon (October 1992). "Putting the Bite in Cenobites". Fangoria. No. 117. pp. 30–33.

- Kane, Paul (2013). The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9781476600697.

External links

[edit]- 1992 films

- 1992 horror films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s English-language films

- American independent films

- American splatter films

- American supernatural horror films

- Dimension Films films

- Films based on works by Clive Barker

- Films directed by Anthony Hickox

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Greensboro, North Carolina

- Films shot in Toronto

- Hellraiser films

- Limbo

- Miramax films

- American religious horror films

- Films scored by Randy Miller (composer)

- English-language horror films