Baalbek

Baalbek

بَعْلَبَكّ | |

|---|---|

Temple of Bacchus | |

| Coordinates: 34°0′22.81″N 36°12′26.36″E / 34.0063361°N 36.2073222°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Baalbek-Hermel |

| District | Baalbek |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bachir Khodr |

| Area | |

• City | 7 km2 (3 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 16 km2 (6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,170 m (3,840 ft) |

| Population | |

• City | 82,608 |

| • Metro | 105,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iv |

| Reference | 294 |

| Inscription | 1984 (8th Session) |

Baalbek[a] (/ˈbɑːlbɛk, ˈbeɪəlbɛk/;[5] Arabic: بَعْلَبَكّ, romanized: Baʿlabakk; Syriac: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about 67 km (42 mi) northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate.[6] In 1998, the city had a population of 82,608.[7] Most of the population consists of Shia Muslims, followed by Sunni Muslims and Christians;[7] in 2017, there was also a large presence of Syrian refugees.[8]

Baalbek has a history that dates back at least 11,000 years, encompassing significant periods such as Prehistoric, Canaanite, Hellenistic, and Roman eras. After Alexander the Great conquered the city in 334 BCE, he renamed it Heliopolis (Ἡλιούπολις, Greek for "Sun City"). The city flourished under Roman rule. However, it underwent transformations during the Christianization period and the subsequent rise of Islam following the Arab conquest in the 7th century. In later periods, the city was sacked by the Mongols and faced a series of earthquakes, resulting in a decline in importance during the Ottoman and modern periods.[9]

In the modern era, Baalbek enjoys economic advantages as a sought-after tourist destination.[10] It is known for the ruins of the Roman temple complex, which includes the Temple of Bacchus and the Temple of Jupiter, and was inscribed in 1984 as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Other tourist attractions are the Great Umayyad Mosque, the Baalbek International Festival, the mausoleum of Sit Khawla, and a Roman quarry site named Hajar al-Hibla.[9] Baalbek's tourism sector has encountered challenges due to conflicts in Lebanon, particularly the 1975–1990 civil war, the ongoing Syrian civil war since 2011,[9][11] and the Israel–Hezbollah conflict (2023–present).[12]

Baalbek has been a stronghold of the militant organization Hezbollah since the 1980s. During the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon (1982–2000), the group managed to overpower the Lebanese army in Baalbek and gain control of the city. The settlement was subsequently used as a base to recruit and train men for attacks against Israeli forces.[13][14][15] Hezbollah continues to hold significant political inflience and popular support in Baalbek.[16][17] In the 2022 Lebanese general election the Amal-Hezbollah list won 9 out of 10 seats in the Baalbek-Hermel Governorate.[18]

Israel has conducted numerous airstrikes and raids against military and civilian targets in the Baalbek area in the past decades. For instance, in 2006 during the Operation Sharp and Smooth, Israeli commandos raided a hospital and bombed multiple houses, killing two Hezbollah fighters and at least eleven civilians.[19][20][21] In 2024, during the Israel–Hezbollah conflict, Israel sent forced displacement calls for the entire city.[22][23] Shortly after, Israeli airstrikes killed 19 people, including 8 women.[24]

Name

A few kilometres from the swamp from which the Litani (the classical Leontes) and the Asi (the upper Orontes) flow, Baalbek may be the same as the manbaa al-nahrayn ("Source of the Two Rivers"), the abode of El in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle[25] discovered in the 1920s and a separate serpent incantation.[26][27]

Baalbek was called Heliopolis during the Roman Empire, a latinisation of the Greek Hēlioúpolis (Ἡλιούπολις) used during the Hellenistic period,[28] meaning "Sun City"[29] in reference to the solar cult there. The name is attested under the Seleucids and Ptolemies.[30] However, Ammianus Marcellinus notes that earlier Assyrian names of Levantine towns continued to be used alongside the official Greek ones imposed by the Diadochi, who were successors of Alexander the Great.[31] In Greek religion, Helios was both the sun in the sky and its personification as a god. The local Semitic god Baʿal Haddu was more often equated with Zeus or Jupiter or simply called the "Great God of Heliopolis",[32][b] but the name may refer to the Egyptians' association of Baʿal with their great god Ra.[30][c] It was sometimes described as Heliopolis in Syria or Coelesyria (Latin: Heliopolis Syriaca or Syriae) to distinguish it from its namesake in Egypt. In Catholicism, its titular see is distinguished as Heliopolis in Phoenicia, from its former Roman province Phoenice. The importance of the solar cult is also attested in the name Biḳāʿ al-ʿAzīz borne by the plateau surrounding Baalbek, as it references an earlier solar deity named Aziz. In Greek and Roman antiquity, it was known as Heliopolis. Some of the best-preserved Roman ruins in Lebanon are located here, including one of the largest temples of the Roman empire. The gods worshipped there (Jupiter, Venus, and Bacchus) were equivalents of the Canaanite deities Hadad, Atargatis. Local influences are seen in the planning and layout of the temples, which differ from classic Roman design. [35]

The name BʿLBK appears in the Mishnah, a second-century rabbinic text, as a kind of garlic, shum ba'albeki (שום בעלבכי).[36] It appears in two early 5th-century Syriac manuscripts, a c. 411[34] translation of Eusebius's Theophania[37][38] and a c. 435[39] life of Rabbula, bishop of Edessa.[40][34] It was pronounced as Baʿlabakk (Arabic: بَعْلَبَكّ) in Classical Arabic.[41][27] In Modern Standard Arabic, its vowels are marked as Baʿlabak (بَعْلَبَك)[42] or Baʿlabekk.[43] It is Bʿalbik (بْعَلْبِك, is [ˈbʕalbik]) in Lebanese Arabic.[42]

The etymology of Baalbek has been debated since the 18th century.[35][27] Cook took it to mean "Baʿal (Lord) of the Beka"[34] and Donne as "City of the Sun".[44] Lendering asserts that it is probably a contraction of Baʿal Nebeq ("Lord of the Source" of the Litani River).[29] Steiner proposes a Semitic adaption of "Lord Bacchus", from the classical temple complex.[27]

Nineteenth-century Biblical archaeologists proposed the association of Baalbek with the town of Baalgad in the Book of Joshua;[45] the town of Baalath, one of Solomon's cities in the First Book of Kings;[46][47] Baal-hamon, where Solomon had a vineyard;[48][3] and the "Plain of Aven" in Book of Amos.[49][50]

Ancient history

Prehistory

The hilltop of Tell Baalbek, part of a valley to the east of the northern Beqaa Valley[51] (Latin: Coelesyria),[52] shows signs of almost continual habitation over the last 8–9000 years.[53] It was well-watered both from a stream running from the Rās-el-ʿAin spring SE of the citadel[54] and, during the spring, from numerous rills formed by meltwater from the Anti-Lebanons.[55] Macrobius later credited the site's foundation to a colony of Egyptian or Assyrian priests.[55] The settlement's religious, commercial, and strategic importance was minor enough, however, that it is never mentioned in any known Assyrian or Egyptian record,[56] unless under another name.[3] Its enviable position in a fertile valley, major watershed, and along the route from Tyre to Palmyra should have made it a wealthy and splendid site from an early age.[3][47] During the Canaanite period, the local temples were largely devoted to the Heliopolitan Triad: a male god (Baʿal), his consort (Astarte), and their son (Adon).[57] The site of the present Temple of Jupiter was probably the focus of earlier worship, as its altar was located at the hill's precise summit and the rest of the sanctuary raised to its level.[citation needed]

In Islamic mythology, the temple complex was said to have been a palace of Solomon's[58][d] which was put together by djinn[61][62][63] and given as a wedding gift to the Queen of Sheba;[35] its actual Roman origin remained obscured by the citadel's medieval fortifications as late as the 16th-century visit of the Polish prince Radziwiłł.[60][64]

Antiquity

After Alexander the Great's conquest of Persia in the 330s BC, Baalbek (under its Hellenic name Heliopolis) formed part of the Diadochi kingdoms of Egypt & Syria. It was annexed by the Romans during their eastern wars. The settlers of the Roman colony Colonia Julia Augusta Felix Heliopolitana may have arrived as early as the time of Caesar[3][55] but were more probably the veterans of the 5th and 8th Legions under Augustus,[47][65][34] during which time it hosted a Roman garrison.[3] From 15 BC to AD 193, it formed part of the territory of Berytus. It is mentioned in Josephus,[66] Pliny,[67] Strabo,[68] and Ptolemy[69] and on coins of nearly every emperor from Nerva to Gallienus.[3] The 1st-century Pliny did not number it among the Decapolis, the "Ten Cities" of Coelesyria, while the 2nd-century Ptolemy did.[69] The population likely varied seasonally with market fairs and the schedules of the Indian monsoon and caravans to the coast and interior.[70]

During Classical Antiquity, the city's temple to Baʿal Haddu was conflated first with the worship of the Greek sun god Helios[34] and then with the Greek and Roman sky god under the name "Heliopolitan Zeus" or "Jupiter". The present Temple of Jupiter presumably replaced an earlier one using the same foundation;[e] it was constructed during the mid-1st century and probably completed around AD 60.[f][74] His idol was a beardless golden god in the pose of a charioteer, with a whip raised in his right hand and a thunderbolt and stalks of grain in his left;[77] its image appeared on local coinage and it was borne through the streets during several festivals throughout the year.[75] Macrobius compared the rituals to those for Diva Fortuna at Antium and says the bearers were the principal citizens of the town, who prepared for their role with abstinence, chastity, and shaved heads.[75] In bronze statuary attested from Byblos in Phoenicia and Tortosa in Spain, he was encased in a pillarlike term and surrounded (like the Greco-Persian Mithras) by busts representing the sun, moon, and five known planets.[78] In these statues, the bust of Mercury is made particularly prominent; a marble stela at Massilia in Transalpine Gaul shows a similar arrangement but enlarges Mercury into a full figure.[78] Local cults also revered the Baetylia, black conical stones considered sacred to Baʿal.[70] One of these was taken to Rome by the emperor Elagabalus, a former priest "of the sun" at nearby Emesa,[79] who erected a temple for it on the Palatine Hill.[70] Heliopolis was a noted oracle and pilgrimage site, whence the cult spread far afield, with inscriptions to the Heliopolitan god discovered in Athens, Rome, Pannonia, Venetia, Gaul, and near the Wall in Britain.[76] The Roman temple complex grew up from the early part of the reign of Augustus in the late 1st century BC until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century. (The 6th-century chronicles of John Malalas of Antioch, which claimed Baalbek as a "wonder of the world",[79] credited most of the complex to the 2nd-century Antoninus Pius, but it is uncertain how reliable his account is on the point.)[60] By that time, the complex housed three temples on Tell Baalbek: one to Jupiter Heliopolitanus (Baʿal), one to Venus Heliopolitana (Ashtart), and a third to Bacchus. On a nearby hill, a fourth temple was dedicated to the third figure of the Heliopolitan Triad, Mercury (Adon or Seimios[80]). Ultimately, the site vied with Praeneste in Italy as the two largest sanctuaries in the Western world.[citation needed]

The emperor Trajan consulted the site's oracle twice. The first time, he requested a written reply to his sealed and unopened question; he was favorably impressed by the god's blank reply as his own paper had been empty.[81] He then inquired whether he would return alive from his wars against Parthia and received in reply a centurion's vine staff, broken to pieces.[82] In AD 193, Septimius Severus granted the city ius Italicum rights.[83][g] His wife Julia Domna and son Caracalla toured Egypt and Syria in AD 215; inscriptions in their honour at the site may date from that occasion; Julia was a Syrian native whose father had been an Emesan priest "of the sun" like Elagabalus.[79]

The town became a battleground upon the rise of Christianity.[80][h] Early Christian writers such as Eusebius (from nearby Caesarea) repeatedly execrated the practices of the local pagans in their worship of the Heliopolitan Venus. In AD 297, the actor Gelasinus converted in the middle of a scene mocking baptism; his public profession of faith provoked the audience to drag him from the theater and stone him to death.[80][3] In the early 4th century, the deacon Cyril defaced many of the idols in Heliopolis; he was killed and (allegedly) cannibalised.[80] Around the same time, Constantine, though not yet a Christian, demolished the goddess' temple, raised a basilica in its place, and outlawed the locals' ancient custom of prostituting women before marriage.[80] Bar Hebraeus also credited him with ending the locals' continued practice of polygamy.[86] The enraged locals responded by raping and torturing Christian virgins.[80] They reacted violently again under the freedom permitted to them by Julian the Apostate.[3] The city was so noted for its hostility to the Christians that Alexandrians were banished to it as a special punishment.[3] The Temple of Jupiter, already greatly damaged by earthquakes,[87] was demolished under Theodosius in 379 and replaced by another basilica (now lost), using stones scavenged from the pagan complex.[88] The Easter Chronicle states he was also responsible for destroying all the lesser temples and shrines of the city.[89] Around the year 400, Rabbula, the future bishop of Edessa, attempted to have himself martyred by disrupting the pagans of Baalbek but was only thrown down the temple stairs along with his companion.[88] It became the seat of its own bishop as well.[3] Under the reign of Justinian, eight of the complex's Corinthian columns were disassembled and shipped to Constantinople for incorporation in the rebuilt Hagia Sophia sometime between 532 and 537.[citation needed] Michael the Syrian claimed the golden idol of Heliopolitan Jupiter was still to be seen during the reign of Justin II (560s & 570s),[88] and, up to the time of its conquest by the Muslims, it was renowned for its palaces, monuments, and gardens.[90]

Middle Ages and early modernity

Baalbek was occupied by the Muslim army in AD 634 (AH 13),[88] in 636,[33] or under Abu ʿUbaidah following the Byzantine defeat at Yarmouk in 637 (AH 16),[citation needed] either peacefully and by agreement[35] or following a heroic defense and yielding 2,000 oz (57 kg) of gold, 4,000 oz (110 kg) of silver, 2000 silk vests, and 1000 swords.[90] The ruined temple complex was fortified under the name al-Qala' (lit. "The Fortress")[88] but was sacked with great violence by the Damascene caliph Marwan II in 748, at which time it was dismantled and largely depopulated.[90] It formed part of the district of Damascus under the Umayyads and Abbasids before being conquered by Fatimid Egypt in 942.[35] In the mid-10th century, it was said to have "gates of palaces sculptured in marble and lofty columns also of marble" and that it was the most "stupendous" and "considerable" location in the whole of Syria.[33] It was sacked and razed by the Byzantines under John I in 974,[35] raided by Basil II in 1000,[91] and occupied by Salih ibn Mirdas, emir of Aleppo, in 1025.[35]

In 1075, it was finally lost to the Fatimids on its conquest by Tutush I, Seljuk emir of Damascus.[35] It was briefly held by Muslim ibn Quraysh, emir of Aleppo, in 1083; after its recovery, it was ruled in the Seljuks' name by the eunuch Gümüshtegin until he was deposed for conspiring against the usurper Toghtekin in 1110.[35] Toghtekin then gave the town to his son Buri. Upon Buri's succession to Damascus on his father's death in 1128, he granted the area to his son Muhammad.[35] After Buri's murder, Muhammad successfully defended himself against the attacks of his brothers Ismaʿil and Mahmud and gave Baalbek to his vizier Unur.[35] In July 1139, Zengi, atabeg of Aleppo and stepfather of Mahmud, besieged Baalbek with 14 catapults. The outer city held until 10 October and the citadel until the 21st,[92] when Unur surrendered upon a promise of safe passage.[93] In December, Zengi negotiated with Muhammad, offering to trade Baalbek or Homs for Damascus, but Unur convinced the atabeg to refuse.[92] Zengi strengthened its fortifications and bestowed the territory on his lieutenant Ayyub, father of Saladin. Upon Zengi's assassination in 1146, Ayyub surrendered the territory to Unur, who was acting as regent for Muhammad's son Abaq. It was granted to the eunuch Ata al-Khadim,[35] who also served as viceroy of Damascus.

In December 1151, it was raided by the garrison of Banyas as a reprisal for its role in a Turcoman raid on Banyas.[94] Following Ata's murder, his nephew Dahhak, emir of the Wadi al-Taym, ruled Baalbek. He was forced to relinquish it to Nur ad-Din in 1154[35] after Ayyub had successfully intrigued against Abaq from his estates near Baalbek. Ayyub then administered the area from Damascus on Nur ad-Din's behalf.[95] In the mid-12th century, Idrisi mentioned Baalbek's two temples and the legend of their origin under Solomon;[96] it was visited by the Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela in 1170.[60]

Baalbek's citadel served as a jail for Crusaders taken by the Zengids as prisoners of war.[97] In 1171, these captives successfully overpowered their guards and took possession of the castle from its garrison. Muslims from the surrounding area gathered, however, and entered the castle through a secret passageway shown to them by a local. The Crusaders were then massacred.[97]

Three major earthquakes occurred in the 12th century, in 1139, 1157, and 1170.[90] The one in 1170 ruined Baalbek's walls and, though Nur ad-Din repaired them, his young heir Ismaʿil was made to yield it to Saladin by a 4-month siege in 1174.[35] Having taken control of Damascus on the invitation of its governor Ibn al-Muqaddam, Saladin rewarded him with the emirate of Baalbek following the Ayyubid victory at the Horns of Hama in 1175.[98] Baldwin, the young leper king of Jerusalem, came of age the next year, ending the Crusaders' treaty with Saladin.[99] His former regent, Raymond of Tripoli, raided the Beqaa Valley from the west in the summer, suffering a slight defeat at Ibn al-Muqaddam's hands.[100] He was then joined by the main army, riding north under Baldwin and Humphrey of Toron;[100] they defeated Saladin's elder brother Turan Shah in August at Ayn al-Jarr and plundered Baalbek.[97] Upon the deposition of Turan Shah for neglecting his duties in Damascus, however, he demanded his childhood home[101] of Baalbek as compensation. Ibn al-Muqaddam did not consent and Saladin opted to invest the city in late 1178 to maintain peace within his own family.[102] An attempt to pledge fealty to the Christians at Jerusalem was ignored on behalf of an existing treaty with Saladin.[103] The siege was maintained peacefully through the snows of winter, with Saladin waiting for the "foolish" commander and his garrison of "ignorant scum" to come to terms.[104] Sometime in spring, Ibn al-Muqaddam yielded and Saladin accepted his terms, granting him Baʿrin, Kafr Tab, and al-Maʿarra.[104][105] The generosity quieted unrest among Saladin's vassals through the rest of his reign[102] but led his enemies to attempt to take advantage of his presumed weakness.[104] He did not permit Turan Shah to retain Baalbek very long, though, instructing him to lead the Egyptian troops returning home in 1179 and appointing him to a sinecure in Alexandria.[98] Baalbek was then granted to his nephew Farrukh Shah, whose family ruled it for the next half-century.[98] When Farrukh Shah died three years later, his son Bahram Shah was only a child but he was permitted his inheritance and ruled til 1230.[35] He was followed by al-Ashraf Musa, who was succeeded by his brother as-Salih Ismail,[35] who received it in 1237 as compensation for being deprived of Damascus by their brother al-Kamil.[106] It was seized in 1246 after a year of assaults by as-Salih Ayyub, who bestowed it upon Saʿd al-Din al-Humaidi.[35] When as-Salih Ayyub's successor Turan Shah was murdered in 1250, al-Nasir Yusuf, the sultan of Aleppo, seized Damascus and demanded Baalbek's surrender. Instead, its emir did homage and agreed to regular payments of tribute.[35]

The Mongolian general Kitbuqa took Baalbek in 1260 and dismantled its fortifications. Later in the same year, however, Qutuz, the sultan of Egypt, defeated the Mongols and placed Baalbek under the rule of their emir in Damascus.[35] Most of the city's still-extant fine mosque and fortress architecture dates to the reign of the sultan Qalawun in the 1280s.[citation needed] By the early 14th century, Abulfeda the Hamathite was describing the city's "large and strong fortress".[107] The revived settlement was again destroyed by a flood on 10 May 1318, when water from the east and northeast made holes 30 m (98 ft) wide in walls 4 m (13 ft) thick.[108] 194 people were killed and 1500 houses, 131 shops, 44 orchards, 17 ovens, 11 mills, and 4 aqueducts were ruined, along with the town's mosque and 13 other religious and educational buildings.[108] In 1400, Timur pillaged the town,[109] and there was further destruction from a 1459 earthquake.[110]

Early modernity

In 1516, Baalbek was conquered with the rest of Syria by the Ottoman sultan Selim the Grim.[110] In recognition of their prominence among the Shiites of the Beqaa Valley, the Ottomans awarded the sanjak of Homs and local iltizam concessions to Baalbek's Harfush family. Like the Hamadas, the Harfush emirs were involved on more than one occasion in the selection of Church officials and the running of local monasteries.

Tradition holds that many Christians quit the Baalbek region in the eighteenth century for the newer, more secure town of Zahlé on account of the Harfushes' oppression and rapacity, but more critical studies have questioned this interpretation, pointing out that the Harfushes were closely allied to the Orthodox Ma'luf family of Zahlé (where indeed Mustafa Harfush took refuge some years later) and showing that depredations from various quarters as well as Zahlé's growing commercial attractiveness accounted for Baalbek's decline in the eighteenth century. What repression there was did not always target the Christian community per se. The Shiite 'Usayran family, for example, is also said to have left Baalbek in this period to avoid expropriation by the Harfushes, establishing itself as one of the premier commercial households of Sidon and later even serving as consuls of Iran.[111]

From the 16th century, European tourists began to visit the colossal and picturesque ruins.[87][112][i] Donne hyperbolised "No ruins of antiquity have attracted more attention than those of Heliopolis, or been more frequently or accurately measured and described."[70] Misunderstanding the temple of Bacchus as the "Temple of the Sun", they considered it the best-preserved Roman temple in the world.[citation needed] The Englishman Robert Wood's 1757 Ruins of Balbec[2] included carefully measured engravings that proved influential on British and Continental Neoclassical architects. For example, details of the Temple of Bacchus's ceiling inspired a bed[136] and ceiling by Robert Adam and its portico inspired that of St George's in Bloomsbury.[137]

During the 18th century, the western approaches were covered with attractive groves of walnut trees,[61] but the town itself suffered badly during the 1759 earthquakes, after which it was held by the Metawali, who again feuded with other Lebanese tribes.[citation needed] Their power was broken by Jezzar Pasha, the rebel governor of Acre, in the last half of the 18th century.[citation needed] All the same, Baalbek remained no destination for a traveller unaccompanied by an armed guard.[citation needed] Upon the pasha's death in 1804, chaos ensued until Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt occupied the area in 1831, after which it again passed into the hands of the Harfushes.[110] In 1835, the town's population was barely 200 people.[129] In 1850, the Ottomans finally began direct administration of the area, making Baalbek a kaza under the Damascus Eyalet and its governor a kaymakam.[110]

Excavations

Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany and his wife passed through Baalbek on 1 November 1898,[87] on their way to Jerusalem. He noted both the magnificence of the Roman remains and the drab condition of the modern settlement.[87] It was expected at the time that natural disasters, winter frosts, and the raiding of building materials by the city's residents would shortly ruin the remaining ruins.[107] The archaeological team he dispatched began work within a month. Despite finding nothing they could date prior to Baalbek's Roman occupation,[138] Otto Puchstein and his associates worked until 1904[87] and produced a meticulously researched and thoroughly illustrated series of volumes.[138] Later excavations under the Roman flagstones in the Great Court unearthed three skeletons and a fragment of Persian pottery dated to the 6th–4th centuries BC. The sherd featured cuneiform letters.[139]

In 1977, Jean-Pierre Adam made a brief study suggesting most of the large blocks could have been moved on rollers with machines using capstans and pulley blocks, a process which he theorised could use 512 workers to move a 557 tonnes (614 tons) block.[140][141] "Baalbek, with its colossal structures, is one of the finest examples of Imperial Roman architecture at its apogee", UNESCO reported in making Baalbek a World Heritage Site in 1984.[142] When the committee inscribed the site, it expressed the wish that the protected area include the entire town within the Arab walls, as well as the southwestern extramural quarter between Bastan-al-Khan, the Roman site and the Mameluk mosque of Ras-al-Ain. Lebanon's representative gave assurances that the committee's wish would be honoured. Recent cleaning operations at the Temple of Jupiter discovered the deep trench at its edge, whose study pushed back the date of Tell Baalbek's settlement to the PPNB Neolithic. Finds included pottery sherds including a spout dating to the early Bronze Age.[143] In the summer of 2014, a team from the German Archaeological Institute led by Jeanine Abdul Massih of the Lebanese University discovered a sixth, much larger stone suggested to be the world's largest ancient block. The stone was found underneath and next to the Stone of the Pregnant Woman ("Hajjar al-Hibla") and measures around 19.6 m × 6 m × 5.5 m (64 ft × 20 ft × 18 ft). It is estimated to weigh [144]1,650 tonnes (1,820 tons).[145]

Modern history

Baalbek was connected to the DHP, the French-owned railway concession in Ottoman Syria, on 19 June 1902.[146] It formed a station on the standard-gauge line between Riyaq to its south and Aleppo (now in Syria) to its north.[147] This Aleppo Railway connected to the Beirut–Damascus Railway but—because that line was built to a 1.05-meter gauge—all traffic had to be unloaded and reloaded at Riyaq.[147] Just before the First World War, the population was still around 5000, about 2000 each of Sunnis and Shia Mutawalis[110] and 1000 Orthodox and Maronites.[65] The French general Georges Catroux proclaimed the independence of Lebanon in 1941 but colonial rule continued until 1943. Baalbek still has its railway station[147] but service has been discontinued since the 1970s, originally owing to the Lebanese Civil War.

In March 1974, Musa al-Sadr announced the launching of the "Movement of the Deprived" in front of a rally in Baalbek attended by 75,000 men. Its objective was to stand up for Lebanon's neglected Shia community. In his speech he listed grievances with the Lebanese government, including Baalbek's lack of a secondary school, Shia communities receiving disproportionately less funds from the national budget, most of the homeless being Shia etc. The occasion was a religious one, and there was celebratory gunfire preceding it.[148] He also announced the setting up of military training camps to train villagers in southern Lebanon to protect their homes from Israeli attacks. These camps led to the creation of the Amal Militia.[149]

By the 2000s, Baalbek was frequently described as a stronghold of Hezbollah,[13][14][15] although it also has a large presence of Christians and Sunni Muslims.[150][144] Many of the city's mayors have been Shia, but since 2022, Baalbek has had a Sunni mayor.[144]

Israeli–Lebanon conflict

In 1978, Israel invaded south Lebanon, forcing hundreds of thousands of Shia Muslims to flee.[151] As a result of the invasion, when Hassan Nasrallah returned to Lebanon from his studies in Najaf, he was unable to return to his hometown in the south, and instead settled in Baalbek.[152] Abbas al-Musawi also moved to Baalbek.[152]

In 1982, at the height of another Israeli invasion, Amal split into two factions over Nabih Berri's acceptance of the American plan to evacuate Palestinians from West Beirut. A large number of dissidents, led by Amal's military commander Hussein Musawi moved to Baalbek.[153] Once established in the town the group, which was to evolve into Hizbollah, began to work with Iranian Revolutionary Guards, veterans of the Iran Iraq War. The following year the Iranians established their headquarters in the Sheikh Abdullah barracks in Baalbek.[154] Ultimately there were between 1,500 and 2,000 Revolutionary Guards in Lebanon,[155] with outposts further south in the Shia villages, such as Jebchit.[156]

In 1984, Israel launched raids on Baalbek, killing 100 Lebanese civilians and wounding hundreds inside the city.[157] Israel also bombed a school in the Wavel Palestinian refugee camp next to the city, wounding 150 school children.[157]

On 24/25 June 1999, following elections in Israel and the new administration undecided, the IAF launched two massive air raids across Lebanon. One of the targets was the al Manar radio station's offices in a four-storey building in Baalbek which was completely demolished. The attacks also hit Beirut's power stations and bridges on the roads to the south. An estimated $52 million damage was caused. Eleven Lebanese were killed as well as two Israelis in Kiryat Shmona.[158]

2006 Lebanon War

During the 2006 Lebanon war, many Israeli bombs fell inside the historic Roman town, and some fell as close as 300 meters from the temple of Baalbek.[159] After the war, UNESCO stated that the cracks in the Roman temples had widened.[160] The damage was thought to be due to shockwaves created by the bombs.[161]

More than 250 houses and buildings were destroyed by Israel during the war.[150] Reporters investigating the aftermath found these to be civilian houses and didn't find any evidence of military use.[150]

On the evening of 1 August 2006,[162] hundreds of Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers raided Baalbek and the Dar al-Hikma[163] or Hikmeh Hospital[164] in Jamaliyeh[162] to its north ("Operation Sharp and Smooth"). Their mission was to rescue two captured soldiers, Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, who were abducted by Hezbollah on 12 July 2006. They were transported by helicopter[162] and supported by Apache helicopters and unmanned drones,[163][162] The IDF was acting on information that Goldwasser and Regev were at the hospital. al-Jazeera and other sources claimed the IDF was attempting to capture senior Hezbollah officials, particularly Sheikh Mohammad Yazbek.[164] The hospital had been empty for four days, the most unwell patients having been transferred and the rest sent home.[163] No Israelis were killed;[162] Five civilians were abducted and interrogated by the Israelis, presumably because one shared his name with Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary general of Hezbollah;[165] they were released on August 21.[166]

On August 7, Israel killed 9 civilians in an attack on Brital, just south of Baalbek, and by the subsequent attack on the car leaving the scene for the hospital.[167] A Human Rights Watch investigation showed that none of those killed were combatants, it is likely none were members of Hezbollah, and none of the survivors had any knowledge of any military presence at place of the attack.[168]

On 14 August just before the ceasefire took effect, two Lebanese police and five Lebanese soldiers were killed by a drone strike while driving their van around the still-damaged road through Jamaliyeh.[169]

Tourism

The Roman ruins have been the setting for the long running Baalbek International Festival.

Baalbek's tourism sector suffered significantly due to the Lebanese Civil war (1975–1990). After the civil war ended, tourism gradually saw a resurgence, including opera, orchestras.[170] But it was once again disrupted by Israeli bombings of Baalbek during the 2006 war.[170]

After the 2006 war, conservation work at Lebanon's historic sites began in October that year.[171] The ruins at Baalbek were not directly hit by Israeli bombing but the effects of blasts during the conflict toppled a block of stones at the Roman ruins and existing cracks in the temples of Jupiter and Bacchus were feared to have widened.[171] Frederique Husseini, director-general of Lebanon's Department of Antiquities, requested $550,000 from Europeans to restore Baalbek's souk and another $900,000 for repairs to other damaged structures.[171]

Starting in the early 2000s, Hezbollah organized permanent or temporary exhibitions called "Exposition of the Resistance" which commemorate what is considered to be Lebanese resistance to Israeli occupation. Spanning several hundred square meters, the exhibitions feature defused Israeli weapons, recreated scenes of war, and photos and videos of Lebanese people killed by Israel.[172][173] Starting in 2009, Hezbollah setup an exhibition to commemorate the 2006 war.[172]

During the Syrian civil war, the UK FCO designated areas close to the Syrian border, including Baalbek and the rest of Beqaa valley, as "red zone" – advising against all travel.[174] The US State Department made a similar designation. These designations, prompted by perceived proximity to Syria and clashes between Sunnis and Alawites, discouraged international tourism.[174]

During its 2024 invasion of Lebanon, Israel bombed a restaurant frequented by tourists[144] and damaged the historic Hotel Palmyra.[175] In November, UNESCO gave Baalbek enhanced protection to safeguard against damage to the archaeological site during the invasion; it was one of 34 areas to receive this protection.[176]

Ruins

The Tell Baalbek temple complex, fortified as the town's citadel during the Middle Ages,[110] was constructed from local stone, mostly white granite and a rough white marble.[62] Over the years, it has suffered from the region's numerous earthquakes, the iconoclasm of Christian and Muslim lords,[70] and the reuse of the temples' stone for fortification and other construction. The temples also suffered minor damage from the shockwaves generated by nearby Israeli bombings in the 2006 Lebanon war.[161] The nearby Qubbat Duris, a 13th-century Muslim shrine on the old road to Damascus, is built out of granite columns, apparently removed from Baalbek.[62] Further, the jointed columns were once banded together with iron; many were gouged open[178] or toppled by the emirs of Damascus to get at the metal.[62] As late as the 16th century, the Temple of Jupiter still held 27 standing columns[116] out of an original 58;[179] there were only nine before the 1759 earthquakes[2] and six today.[when?]

The complex is located on a raised plaza erected 5 m (16 ft) over an earlier T-shaped base consisting of a podium, staircase, and foundation walls.[j] These walls were built from about 24 monoliths, at their lowest level weighing approximately 300 tonnes (330 tons) each. The tallest retaining wall, on the west, has a second course of monoliths containing the famous "Three Stones" (Ancient Greek: Τρίλιθον, Trílithon):[54] a row of three stones, each over 19 m (62 ft) long, 4.3 m (14 ft) high, and 3.6 m (12 ft) broad, cut from limestone. They weigh approximately 800 tonnes (880 tons) each.[180] A fourth, still larger stone is called the Stone of the Pregnant Woman: it lies unused in a nearby quarry 800 m (2,600 ft) from the town.[181] Its weight is estimated at 1,000 tonnes (1,100 tons).[182] A fifth, still larger stone weighing approximately 1,200 tonnes (1,300 tons)[183] lies in the same quarry. This quarry was slightly higher than the temple complex,[184][140][185] so no lifting was required to move the stones.[186][187]

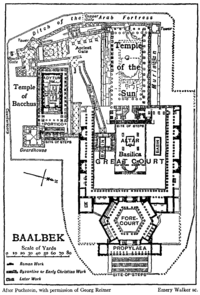

The temple complex was entered from the east through the Propylaea (προπύλαιον, propýlaion) or Portico,[70] consisting of a broad staircase rising 20 feet (6.1 m)[188] to an arcade of 12 columns flanked by 2 towers.[87] Most of the columns have been toppled and the stairs were entirely dismantled for use in the nearby later wall,[54][k] but a Latin inscription remains on several of their bases stating that Longinus, a lifeguard of the 1st Parthian Legion, and Septimius, a freedman, gilded their capitals with bronze in gratitude for the safety of Septimius Severus's son Antoninus Caracalla and empress Julia Domna.[189][l]

Immediately behind the Propylaeum is a hexagonal forecourt[87] reached through a threefold entrance[90] that was added in the mid-3rd century by the emperor Philip the Arab.[citation needed] Traces remain of the two series of columns which once encircled it, but its original function remains uncertain.[87] Donne reckoned it as the town's forum.[70] Badly preserved coins of the era led some to believe this was a sacred cypress grove, but better specimens show that the coins displayed a single stalk of grain instead.[190]

The rectangular Great Court to its west covers around 3 or 4 acres (1.2 or 1.6 ha)[90] and included the main altar for burnt offering, with mosaic-floored lustration basins to its north and south, a subterranean chamber,[191] and three underground passageways 17 ft (5.2 m) wide by 30 ft (9.1 m) high, two of which run east and west and the third connecting them north and south, all bearing inscriptions suggesting their occupation by Roman soldiers.[90] These were surrounded by Corinthian porticoes, one of which was never completed.[191] The columns' bases and capitals were of limestone; the shafts were monoliths of highly polished red Egyptian granite 7.08 m (23.2 ft) high.[191] Six remain standing, out of an original 128.[citation needed] Inscriptions attest that the court was once adorned by portraits of Marcus Aurelius's daughter Sabina, Septimius Severus, Gordian, and Velius Rufus, dedicated by the city's Roman colonists.[191] The entablature was richly decorated but is now mostly ruined.[191] A westward-facing basilica was constructed over the altar during the reign of Theodosius; it was later altered to make it eastward-facing like most Christian churches.[88]

The Temple of Jupiter—once wrongly credited to Helios[192]—lay at the western end of the Great Court, raised another 7 m (23 ft) on a 47.7 m × 87.75 m (156.5 ft × 287.9 ft) platform reached by a wide staircase.[179] Under the Byzantines, it was also known as the "Trilithon" from the three massive stones in its foundation and, when taken together with the forecourt and Great Court, it is also known as the Great Temple.[177] The Temple of Jupiter proper was circled by a peristyle of 54 unfluted Corinthian columns:[193] 10 in front and back and 19 along each side.[179] The temple was ruined by earthquakes,[87] destroyed and pillaged for stone under Theodosius,[88] and 8 columns were taken to Constantinople (Istanbul) under Justinian for incorporation into the Hagia Sophia.[citation needed] Three fell during the late 18th century.[90] 6 columns, however, remain standing along its south side with their entablature.[179] Their capitals remain nearly perfect on the south side, while the Beqaa's winter winds have worn the northern faces almost bare.[194] The architrave and frieze blocks weigh up to 60 tonnes (66 tons) each, and one corner block over 100 tonnes (110 tons), all of them raised to a height of 19 m (62.34 ft) above the ground.[195] Individual Roman cranes were not capable of lifting stones this heavy. They may have simply been rolled into position along temporary earthen banks from the quarry.[194] The Julio-Claudian emperors enriched its sanctuary in turn. In the mid-1st century, Nero built the tower-altar opposite the temple. In the early 2nd century, Trajan added the temple's forecourt, with porticos of pink granite shipped from Aswan at the southern end of Egypt.[citation needed]

The Temple of Bacchus—once wrongly credited to Jupiter[196][m]—may have been completed under Septimius Severus in the 190s, as his coins are the first to show it beside the Temple of Jupiter.[citation needed] It is the best preserved of the sanctuary's structures, as the other rubble from its ruins protected it.[citation needed] It is enriched by some of the most refined reliefs and sculpture to survive from antiquity.[178] The temple is surrounded by forty-two columns—8 along each end and 15 along each side[197]—nearly 20 m (66 ft) in height.[citation needed] These were probably erected in a rough state and then rounded, polished, and decorated in position.[178][n] The entrance was preserved as late as Pococke[122] and Wood,[2] but the keystone of the lintel had slid 2 ft (1 m) following the 1759 earthquakes; a column of rough masonry was erected in the 1860s or '70s to support it.[197] The 1759 earthquakes also damaged the area around the soffit's famed inscription of an eagle,[112] which was entirely covered by the keystone's supporting column. The area around the inscription of the eagle was greatly damaged by the 1759 earthquake.[112] The interior of the temple is divided into a 98 ft (30 m) nave and a 36 ft (11 m) adytum or sanctuary[197] on a platform raised 5 ft (2 m) above it and fronted by 13 steps.[178] The screen between the two sections once held reliefs of Neptune, Triton, Arion and his dolphin, and other marine figures[121] but these have been lost.[178] The temple was used as a kind of donjon for the medieval Arab and Turkish fortifications,[110] although its eastern steps were lost sometime after 1688.[198] Much of the portico was incorporated into a huge wall directly before its gate, but this was demolished in July 1870 by Barker[who?] on orders from Syria's governor Rashid Pasha.[197] Two spiral staircases in columns on either side of the entrance lead to the roof.[112]

The Temple of Venus—also known as the Circular Temple or Nymphaeum[189]—was added under Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century[citation needed] but destroyed under Constantine, who raised a basilica in its place.[112] Jessup considered it the "gem of Baalbek".[189] It lies about 150 yd (140 m) from the southeast corner of the Temple of Bacchus.[189] It was known in the 19th century as El Barbara[189] or Barbarat el-Atikah (St Barbara's), having been used as a Greek Orthodox church into the 18th century.[112][o]

The ancient walls of Heliopolis had a circumference of a little less than 4 mi (6 km).[70] Much of the extant fortifications around the complex date to the 13th century[88] reconstruction undertaken by the Mamluk sultan Qalawun following the devastation of the earlier defenses by the Mongol army under Kitbuqa.[35] This includes the great southeast tower.[110] The earliest round of fortifications were two walls to the southwest of the Temples of Jupiter and Bacchus.[110] The original southern gateway with two small towers was filled in and replaced by a new large tower flanked by curtains,[clarification needed] probably under Buri or Zengi.[110] Bahramshah replaced that era's southwest tower with one of his own in 1213 and built another in the northwest in 1224; the west tower was probably strengthened around the same time.[110] An inscription dates the barbican-like strengthening of the southern entrance to around 1240.[110] Qalawun relocated the two western curtains[clarification needed] nearer to the western tower, which was rebuilt with great blocks of stone. The barbican was repaired and more turns added to its approach.[110] From around 1300, no alterations were made to the fortifications apart from repairs such as Sultan Barkuk's restoration of the moat in preparation for Timur's arrival.[110]

Material from the ruins is incorporated into a ruined mosque north of downtown[199] and probably also in the Qubbat Duris on the road to Damascus.[199] In the 19th century, a "shell-topped canopy" from the ruins was used nearby as a mihrab, propped up to show locals the direction of Mecca for their daily prayers.[199]

Tomb of Husayn's daughter

Under a white dome further towards town is the tomb of Khawla, daughter of Hussein and granddaughter of Ali, who died in Baalbek while Husayn's family was being transported as prisoners to Damascus.[200][201]

Ecclesiastical history

Heliopolis (in Phoenicia; not to be confused with the Egyptian bishopric Heliopolis in Augustamnica) was a bishopric under Roman and Byzantine rule, but it disappeared due to the Islamic rule.

In 1701, Eastern Catholics (Byzantine Rite) established anew an Eparchy of Baalbek, which in 1964 was promoted to the present Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Baalbek.[citation needed]

Titular see

In the Latin Church, the Ancient diocese was only nominally restored (no later than 1876) as Titular archbishopric of Heliopolis (Latin) / Eliopoli (Curiate Italian), demoted in 1925 to Episcopal Titular bishopric, promoted back in 1932, with its name changed (avoiding Egyptian confusion) in 1933 to (non-Metropolitan) Titular archbishopric of Heliopolis in Phoenicia.

The title has not been assigned since 1965. It was held by:[202]

- Titular Archbishop: Luigi Poggi (1876.09.29 – death 1877.01.22) on emeritate (promoted) as former Bishop of Rimini (Italy) (1871.10.27 – 1876.09.29)

- Titular Archbishop: Mario Mocenni (1877.07.24 – 1893.01.16) as papal diplomat : Apostolic Delegate to Colombia (1877.08.14 – 1882.03.28), Apostolic Delegate to Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Honduras (1877.08.14 – 1882.03.28), Apostolic Delegate to Ecuador (1877.08.14 – 1882.03.28), Apostolic Delegate to Peru and Bolivia (1877.08.14 – 1882.03.28), Apostolic Delegate to Venezuela (1877.08.14 – 1882.03.28), Apostolic Internuncio to Brazil (1882.03.28 – 1882.10.18), created Cardinal-Priest of S. Bartolomeo all'Isola (1893.01.19 – 1894.05.18), promoted Cardinal-Bishop of Sabina (1894.05.18 – death 1904.11.14)

- Titular Archbishop: Augustinus Accoramboni (1896.06.22 – death 1899.05.17), without prelature

- Titular Archbishop: Robert John Seton (1903.06.22 – 1927.03.22), without prelature

- Titular Bishop: Gerald O'Hara (1929.04.26 – 1935.11.26) as Auxiliary Bishop of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, USA) (1929.04.26 – 1935.11.26), later Bishop of Savannah (USA) (1935.11.26 – 1937.01.05), restyled (only) Bishop of Savannah–Atlanta (USA) (1937.01.05 – 1950.07.12), promoted Archbishop-Bishop of Savannah (1950.07.12 – 1959.11.12), also Apostolic Nuncio (papal ambassador) to Ireland (1951.11.27 – 1954.06.08), Apostolic Delegate to Great Britain (1954.06.08 – death 1963.07.16) and Titular Archbishop of Pessinus (1959.11.12 – 1963.07.16)

- Titular Archbishop: Alcide Marina, C.M. (1936.03.07 – death 1950.09.18), mainly as papal diplomat : Apostolic Delegate to Iran (1936.03.07 – 1945), Apostolic Administrator of Roman Catholic Apostolic Vicariate of Constantinople (Turkey) (1945–1947) and Apostolic Delegate to Turkey (1945–1947), Apostolic Nuncio to Lebanon (1947 – 1950.09.18)

- Titular Archbishop: Daniel Rivero Rivero (1951 – death 1960.05.23) (born Bolivia) on emeritate, formerly Titular Bishop of Tlous (1922.05.17 – 1931.03.30) as Coadjutor Bishop of Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Bolivia) (1922.05.17 – 1931.03.30) succeeding as Bishop of Santa Cruz de la Sierra (1931.03.30 – 1940.02.03), Metropolitan Archbishop of Sucre (Bolivia) (1940.02.03 – 1951)

- Titular Archbishop: Raffaele Calabria (1960.07.12 – 1962.01.01) as Coadjutor Archbishop of Benevento (Italy) (1960.07.12 – 1962.01.01), succeeding as Metropolitan Archbishop of Benevento (1962.01.01 – 1982.05.24); previously Titular Archbishop of Soteropolis (1950.05.06 – 1952.07.10) as Coadjutor Archbishop of Otranto (Italy) (1950.05.06 – 1952.07.10), succeeding as Metropolitan Archbishop of Otranto (Italy) (1952.07.10 – 1960.07.12)

- Titular Archbishop: Ottavio De Liva (1962.04.18 – death 1965.08.23) as papal diplomat : Apostolic Internuncio to Indonesia (1962.04.18 – 1965.08.23).

Climate

Baalbek has a mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa) with significant continental influences. It is located in one of the drier regions of the country, giving it an annual average of 450 millimetres or 18 inches of rainfall compared with 800 to 850 millimetres (31 to 33 in) in coastal areas, overwhelmingly concentrated in the months from November to April. Baalbek has hot rainless summers with cool (and occasionally snowy) winters. Autumn and spring are mild and fairly rainy.

| Climate data for Baalbek (Chlifa), elevation 1,000 m (3,300 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

23.0 (73.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

15.0 (59.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 96 (3.8) |

89 (3.5) |

58 (2.3) |

28 (1.1) |

12 (0.5) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

9 (0.4) |

43 (1.7) |

72 (2.8) |

411 (16.1) |

| Source: FAO[203] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Saint Barbara (273–306)

- Callinicus of Heliopolis (c. 600 – c. 680), chemist and inventor

- Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i (707–774)

- Qusta ibn Luqa (820–912), mathematician and translator

- Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir (1070s–1162)

- Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī (1547–1621), Lebanese-Iranian scholar, philosopher, architect, mathematician, astronomer

- Rahme Haider (1880s–1939), American lecturer from Baalbek

- Khalil Mutran (1872–1949), poet and journalist

- Harfush dynasty

In popular culture

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration

Ruins at Balbec. is on a painting by William Henry Bartlett entitled Six detached pillars of the Great Temple at Balbec, and was published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839.[204]

Ruins at Balbec. is on a painting by William Henry Bartlett entitled Six detached pillars of the Great Temple at Balbec, and was published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839.[204] - Ameen Rihani's The Book of Khalid (1911), the first English novel by an Arab-American, is set in Baalbek.

- The events of the 1984 novel Les fous de Baalbek (SAS, #74) by Gérard de Villiers take place in Baalbek.

Twin towns

Baalbek is twinned with:

Gallery

-

The Round Temple and the Temple of the Muses located outside the sanctuary complex

-

Remains of the Propylaeum, the eastern entrance to the site

-

The Great Court of Temples Complex

-

Temple of Venus

-

Massive columns of the Temple of Jupiter

-

An 1873 German map of Asia Minor & Syria, with relief illustrating the Beqaa (El Bekaa) valley

-

Panorama, around 1870, by Félix Bonfils

-

Baalbek in 1910, after the arrival of rail

-

The ruins of Baalbek facing west from the hexagonal forecourt in the 19th century

-

The "Stone of the Pregnant Woman" in the early 20th century, the Temple of Jupiter in the background

See also

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- List of Catholic dioceses in Lebanon

- List of colossal sculptures in situ – Large sculptures carved into a material that remain at location

- List of largest monoliths

- Triparadeisos – Ancient settlement in Lebanon

Notes

- ^ Also spelled Ba'labek,[1] Balbec,[2] Baalbec[3] and Baalbeck.[4]

- ^ The name also appears in the Hellenized form Balanios and Baal Helion in records describing the acts of Theodosius's reign.[33]

- ^ The Egyptian priests' claims that Heliopolis represented a direct descendant of Ra's cult at Iunu, however, is almost certainly mistaken.[34]

- ^ Commonly mistaken by European visitors to have been the one described in the Biblical First Book of Kings.[59][60]

- ^ Daniel Lohmann wrote that, "due to the lack of remains of temple architecture, it can be assumed that the temple this terrace was built for was never completed or entirely destroyed before any new construction started..."[71][page needed] "The unfinished pre-Roman sanctuary construction was incorporated into a master plan of monumentalisation. Apparently challenged by the already huge pre-Roman construction, the early imperial Jupiter sanctuary shows both an architectural megalomaniac design and construction technique in the first half of the first century AD."[72]

- ^ "It is apparent from a graffito on one of the columns of the Temple of Jupiter that that building was nearing completion in 60 A.D."[73]

- ^ Coins of Septimius Severus bear the legend COL·HEL·I·O·M·H: Colonia Heliopolis Iovi Optimo Maximo Helipolitano.[3]

- ^ It is mentioned, inter alia, by Sozomen[84] and Theodoret.[85]

- ^ Notable visitors[112][52] included Baumgarten (1507),[113] Belon (1548),[114][115] Thévet (1550),[116] von Seydlitz (1557),[117] Radziwiłł (1583),[64] Quaresmio (1620),[118] Monconys (1647),[119] de la Roque (1688),[120] Maundrell (1699),[121] Pococke (1738),[122] Wood and Dawkins (1751),[2] Volney (1784),[123] Richardson (1818),[124] Chesney (1830),[125][126] Lamartine (1833),[127] Marmont (1834),[128] Addison (1835),[129] Lindsay (1837),[130] Robinson (1838[131] & 1852),[132] Wilson (1843),[133] De Saulcy (1851),[134] and Frauberger (19th c.).[135]

- ^ "Current survey and interpretation, show that a pre-Roman floor level about 5 m lower than the late Great Roman Courtyard floor existed underneath".[72]

- ^ The staircase is shown intact on a coin from the reign of the emperor Philip the Arab.[54]

- ^ The inscriptions were distinct in the 18th century[2] but becoming illegible by the end of the 19th:[189]

[I. O.] M. DIIS HELIVPOL. PRO SAL.

[ET] VICTORIIS D. N. ANTONINI PII FEL. AVG. ET IVLIÆ AVG. MATRIS D. N. CAST. SENAT. PATR., AVR. ANT. LONGINVS SPECVL. LEG. I.

[ANT]ONINIANÆ CAPITA COLVMNARVM DVA ÆREA AVRO INLVMINATA SVA PECVNIA EX VOTO L. A. S.[87]

and

[I. O.] M. PRO SAL[VTE] D. [N.] IMP. ANTONIN[I PII FELICIS...]

[...SEP]TIMI[VS...] BAS AVG. LIB. CAPVT COLVMNÆ ÆNEUM AVRO INL[VMINAT]VM VOTVM SVA PECVNIA L. [A. S.][87] - ^ It has also been misattributed to Apollo and Helios.[90] The locals once knew it as the Dar es-Sa'adeh or "Court of Happiness".[197]

- ^ The cornice of the exaedrum in the northwest corner remains partially sculpted and partially plain.[178]

- ^ In the 1870s and '80s, its Metawali caretaker Um Kasim would demand bakshish from visitors and for use of the olive oil lamps used to make vows to St Barbara.[189]

References

- ^ Cook's (1876).

- ^ a b c d e f Wood (1757).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l EB (1878), p. 176.

- ^ إتحاد بلديات غربي بعلبك [West Baalbeck Municipalities Union] (in Arabic). 2013. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^

- Olausson, Lena (2 August 2006). "How to Say: Baalbek". London: BBC. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- "Baalbek". Merriam–Webster. 2020.

- "Baalbek". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020.

- ^ "Mohafazah de Baalbek-Hermel". Localiban. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ a b Wolfgang Gockel; Helga Bruns (1998). Syria – Lebanon (illustrated ed.). Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 202. ISBN 9783886181056.

- ^ "Ba'albak (District, Lebanon) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Najem, Tom; Amore, Roy C.; Abu Khalil, As'ad (2021). Historical Dictionary of Lebanon. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East (2nd ed.). Lanham Boulder New York London: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-5381-2043-9.

- ^ Israeli war with Hezbollah cripples tourism in ancient city of Baalbek. Retrieved 1 November 2024 – via apnews.com.

- ^ Paturel, Simone (2019). Baalbek-Heliopolis, the Bekaa, and Berytus from 100 BCE to 400 CE: A Landscape Transformed. BRILL. p. 6. ISBN 9789004400733.

The town of Baalbek is a Hezbollah stronghold and was the scene of Israeli commando raids in 2006 and some rocket fire from Syria in recent years due to the civil war.

- ^ Israeli war with Hezbollah cripples tourism in ancient city of Baalbek. Retrieved 18 November 2024 – via apnews.com.

- ^ a b Hamzeh, Ahmad Nizar (2004). In the Path of Hizbullah. Syracuse University Press. pp. 100–128. ISBN 978-0-8156-3053-1.

- ^ a b Malthaner, Stefan (2011). Mobilizing the Faithful: Militant Islamist Groups and Their Constituencies. Campus Verlag. pp. 82–83, 182–184, 236–242. ISBN 9783593394121.

- ^ a b Levitt, Matthew (2013). Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon's Party of God (Updated ed.). Georgetown University Press (published 2024). p. 129. ISBN 9781647125325.

- ^ Chaddad, Rita (2021). "Culture, tourism, and territory: Analyzing discourses and perceptions of actors in Byblos and Baalbek in Lebanon". Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change. 19 (6): 805–818. doi:10.1080/14766825.2020.1802470.

- ^ "Inside the Lebanese Valley Where Israel Is Bombarding Hezbollah". The New York Times. 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Here's The List Of Who Won In The Bekaa III (Baalbek-Hermel) District In Lebanon's Elections 2022". 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Why They Died: Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 19 (5): 124–129.

- ^ Pedahzur, Ami (2009). The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. Columbia University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780231140423.

- ^ Andrew Lee Butters (2 August 2006). "Behind the Battle for Baalbek". Time. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "Israel conducts air raid on Baalbek, Hezbollah stronghold in Lebanon". Reuters. 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Israeli Airstrike Hits Hezbollah Stronghold in Northeast Lebanon". Voice of America. 23 March 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Al Jazeera Staff. "What is Lebanon's ancient city of Baalbek and why is Israel targeting it?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ KTU 1.4 IV 21.

- ^ KTU 1.100.3.

- ^ a b c d Steiner (2009).

- ^ "Baalbek". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ a b Lendering (2013).

- ^ a b Jidejian (1975), p. 5.

- ^ Amm. Marc., Hist., Bk XIV, Ch. 8, §6 Archived 1 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jidejian (1975), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Jessup (1881), p. 473.

- ^ a b c d e f Cook (1914), p. 550.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t EI (1913), p. 543.

- ^ Mishnah, Maaserot 5:8

- ^ Brit. Mus. Add. 12150.

- ^ Eusebius, Theophania, 2.14.

- ^ Burkitt (1904), p. 51.

- ^ Overbeck (1865), p. 196.

- ^ Arastu (2014), p. 616.

- ^ a b "Arabic" (PDF). ALA-LC Romanization Tables. Washington: Library of Congress. 2015.

- ^ EI (1913).

- ^ DGRG (1878).

- ^ Josh. 11:17

- ^ 1 Kings 9:17–18

- ^ a b c New Class. Dict. (1862).

- ^ Song of Songs 8:11.

- ^ Amos 1:5,

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 468.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 453.

- ^ a b EB (1911).

- ^ "Lebanon, Baalbek". Berlin: German Archaeological Institute. 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Jessup (1881), p. 456.

- ^ a b c DGRG (1878), p. 1036.

- ^ Hélène Sader.[where?]

- ^ Jidejian (1975), p. 47.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 470.

- ^ 1 Kings 7:2–7.

- ^ a b c d CT (2010).

- ^ a b Volney (1787), p. 224.

- ^ a b c d DGRG (1878), p. 1038.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 454.

- ^ a b Radziwiłł (1601).

- ^ a b EB (1911), p. 89.

- ^ Josephus, Ant., XIV.3–4.

- ^ Pliny, Nat. Hist., V.22.

- ^ Strabo, Geogr., Bk. 14, Ch. 2, §10. (in Greek)

- ^ a b Ptolemy, Geogr., Bk. V, Ch. 15, §22 Archived 29 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f g h DGRG (1878), p. 1037.

- ^ Lohmann (2010).

- ^ a b Lohmann (2010), p. 29.

- ^ Rowland (1956).

- ^ Kropp & al. (2011).

- ^ a b c Macrobius, Saturnalia, Vol. I, Ch. 23.

- ^ a b Cook (1914), p. 552.

- ^ Macrobius,[75] translated in Cook.[76]

- ^ a b Graves (1955), p. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Jessup (1881), p. 471.

- ^ a b c d e f Cook (1914), p. 554.

- ^ Cook (1914), p. 552–553.

- ^ Cook (1914), p. 553.

- ^ Ulpian, De Censibus, Bk. I.

- ^ Sozomen, Hist. Eccles., v.10.

- ^ Theodoret, Hist. Eccles., III.7 & IV.22.

- ^ Bar Hebraeus, Hist. Compend. Dynast., p. 85. (in Latin)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cook (1914), p. 556.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cook (1914), p. 555.

- ^ Niebuhr, Barthold Georg; Dindorf, Ludwig, eds. (1832). "σπθʹ Ὀλυμπιάς" [CCLXXXIX]. Chronicon Paschale. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae (in Greek and Latin). Vol. I. Bonn: Impensis ed. Weberi. p. 561.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i EB (1878), p. 177.

- ^ CMH (1966), p. 634.

- ^ a b Venning & al. (2015), p. 109.

- ^ EI (1936), p. 1225.

- ^ Venning & al. (2015), p. 138.

- ^ Venning & al. (2015), p. 141–142.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 475–476.

- ^ a b c Alouf (1944), p. 94.

- ^ a b c Humphreys (1977), p. 52.

- ^ Lock 2013, p. 63.

- ^ a b Runciman (1951), p. 410.

- ^ Sato (1997), p. 57.

- ^ a b Baldwin (1969), p. 572.

- ^ Köhler (2013), p. 226.

- ^ a b c Lyons & al. (1982), pp. 132–133.

- ^ Sato (1997), p. 58.

- ^ Venning & al. 2015, p. 299.

- ^ a b Jessup (1881), p. 476.

- ^ a b Alouf (1944), p. 96.

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p. xxiii.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n EI (1913), p. 544.

- ^ Stefan Winter (11 March 2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge University Press, Page 166.

- ^ a b c d e f g EB (1878), p. 178.

- ^ Baumgarten (1594).

- ^ Belon (1553).

- ^ Belon (1554).

- ^ a b Thevet (1554).

- ^ Sedlitz (1580).

- ^ Quaresmio (1639).

- ^ Monconys (1665).

- ^ de la Roque (1722).

- ^ a b Maundrell (1703).

- ^ a b Pococke (1745).

- ^ Volney (1787).

- ^ Richardson (1822).

- ^ Chesney (1850).

- ^ Chesney (1868).

- ^ Lamartine (1835).

- ^ Marmont (1837).

- ^ a b Addison (1838).

- ^ Lindsay (1838).

- ^ Robinson (1841).

- ^ Robinson (1856).

- ^ Wilson (1847).

- ^ De Saulcy (1853).

- ^ Frauberger (1892).

- ^ Coote, James. "Adam's Bed: 16 Varieties of (Im)propriety". Austin: Center for American Architecture & Design, University of Texas School of Architecture. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "St George's Church Bloomsbury". Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ a b Wiegand (1925).

- ^ Jidejian (1975), p. 15.

- ^ a b Adam & al. (1999), p. 35.

- ^ Adam (1977).

- ^ "Baalbek". New York: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015..

- ^ Genz (2010).

- ^ a b c d "Lebanon's ancient city of Baalbek bears the scars of Israeli bombs". 24 October 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Kehrer (2014).

- ^ Ludvigsen, Børre (2008). "Lebanon: Railways: Background". Al Mashriq: The Levant. Halden: Østfold University. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Ludvigsen, Børre (2008). "Lebanon: Railways: Riyaq–Homs". Al Mashriq: The Levant. Halden: Østfold University. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Ajami, Fouad (1986) The vanished Imam : Musa al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-025-X p.145

- ^ Hirst, David (2010) Beware of Small States. Lebanon, battleground of the Middle East. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23741-8 p.101

- ^ a b c "Baalbek after the bombs". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Jaber, Hala (Winter–Spring 1999). "Consequences of Imperialism: Hezbollah and the West". The Brown Journal of World Affairs. 6 (1): 168.

- ^ a b Daher, Aurélie (2019). Hezbollah: mobilisation and power. Translated by Randolph, Henry W. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-19-049589-3. OCLC 938989849.

- ^ David Hirst pp.187-188

- ^ David Hirst p.190

- ^ David Hirst p.186

- ^ David Hirst p.235

- ^ a b Khalidi, Rashid. "The Palestinians in Lebanon: Social Repercussions of Israel's Invasion". Middle East Journal. 38 (2): 259.

- ^ Middle East International. No 603, 2 July 1999; Publishers Christopher Mayhew. Dennis Walters; Michael Jansen pp.4-5; Reinoud Leendes pp.5&7

- ^ Archaeology, Current World (3 September 2006). "Lebanon". World Archaeology. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "UNESCO: Lebanon's Ancient Ruins Damaged by War". Voice of America. 31 October 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ a b Brockman, Norbert C. (2011). Encyclopedia of sacred places (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6. OCLC 698626500.

- ^ a b c d e HRW (2007), p. 124.

- ^ a b c Butters, Andrew Lee (2 August 2006). "Behind the Battle for Baalbek". Time. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b Nahla (2 August 2006). "Minute by Minute:: August 2". Lebanon Updates. Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- ^ HRW (2007), p. 127.

- ^ HRW (2007), p. 127–128.

- ^ HRW (2007), p. 137.

- ^ "Why They Died". Human Rights Watch. 5 September 2007.

- ^ HRW (2007), p. 164–165.

- ^ a b Malaspina, Ann (2009). Lebanon. p. 106.

- ^ a b c Karam, Zeina (4 October 2006). "Cleanup to Start at Old Sites in Lebanon". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b Saade, Bashir (2016). Hizbullah and the politics of remembrance: writing the Lebanese nation. Cambridge Middle East studies. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-107-10181-4.

- ^ Daher 2019, p. 119.

- ^ a b "The lost tourists of Lebanon's 'red zone'". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ Khoury, Gilles (11 November 2024). "The violation of our private and collective memories". Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ "Cultural property under enhanced protection Lebanon". Archived from the original on 31 December 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ a b EB (1911), p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f Jessup (1881), p. 459.

- ^ a b c d Cook (1914), p. 560.

- ^ Adam (1977), p. 52.

- ^ Alouf (1944), p. 139.

- ^ Ruprechtsberger (1999), p. 15.

- ^ Ruprechtsberger (1999), p. 17.

- ^ Adam, Jean Pierre; Mathews, Anthony (1999). Roman Building: Materials and Techniques. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-0415208666.

- ^ Hastings (2004), p. 892.

- ^ Hastings, James. A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume IV: (Part II: Shimrath -- Zuzim). The Minerva Group. p. 892. ISBN 978-1-4102-1729-5. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Jeanine Abdul Massih (13 July 2023). "Quarrying Megaliths in Heliolopis Baalbek (Lebanon)". In Barker, Simon J.; Courault, Christopher; Domingo, Javier Á; Maschek, Dominik (eds.). From Concept to Monument: Time and Costs of Construction in the Ancient World: Papers in Honour of Janet DeLaine. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-78969-423-9.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 465.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jessup (1881), p. 466.

- ^ Cook (1914), p. 558–559.

- ^ a b c d e Cook (1914), p. 559.

- ^ Cook (1914), p. 565.

- ^ Jessup (1881), p. 460.

- ^ a b Jessup (1881), p. 462.

- ^ Coulton (1974), p. 16.

- ^ Cook (1914), p. 564.

- ^ a b c d e Jessup (1881), p. 458.

- ^ EB (1878).

- ^ a b c Jessup (1881), p. 467.

- ^ Michel M. Alouf -History of Baalbek 1922 "After the defeat and murder of Hossein by the Ommiads, his family was led captive to Damascus; but Kholat died at Baalbek on her way into exile."

- ^ Nelles Guide Syria – Lebanon -Wolfgang Gockel, Helga Bruns – 1998 – Page 202 3886181057 "Ensconced under a white dome further towards town are the mortal remains of Kholat, daughter of Hussein and granddaughter of."

- ^ "Titular See of Heliopolis in Phœnicia, Lebanon". www.gcatholic.org.

- ^ "World-wide Agroclimatic Data of FAO (FAOCLIM)". Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1838). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1838). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839. Fisher, Son & Co.

- ^ Syaifullah, M. (26 October 2008). "Yogyakarta dan Libanon Bentuk Kota Kembar". Tempo Interaktif. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

Sources and external links

- Google Maps satellite view

- Panoramas of the temples at Lebanon 360 and Discover Lebanon

- Archaeological research in Baalbek from the German Archaeological Institute

- GCatholic – Latin titular see

- Baalbeck International Festival

- Baalbek Railway Station (2006) at Al Mashriq

- Hussey, J.M., ed. (1966). The Byzantine Empire. Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. IV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, William; Anthon, Charles, eds. (1862). "Heliopolis". A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology, and Geography. New York: Harper & Bros. p. 349.

- K., T. (2010). "Baalbek". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (eds.). The Classical Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- "Ba'albek". Cook's Tourists' Handbook for Palestine and Syria. London: T. Cook & Son. 1876. pp. 359–365.

- Donne, William Bodham (1878). "Helio′polis Syriae". In Smith, William (ed.). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, Vol. I. London: John Murray. pp. 1036–1038.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 176–178

- Hogarth, David George (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–90

- Sobernheim, Moritz (1913). "Baalbek". Encyclopaedia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography, and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples. Vol. I (1st ed.). Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 543–544. ISBN 9004082654.

- Zettersteen, K.V. (1936). "Zengī". Encyclopaedia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography, and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples. Vol. VIII (1st ed.). Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 1224–1225. ISBN 9004097961.

- Adam, Jean-Pierre (1977). "À propos du trilithon de Baalbek: Le transport et la mise en oeuvre des mégalithes" [About the Baalbeck Trilithon: The Transport and Use of the Megaliths]. Syria (in French). 54 (1/2): 31–63. doi:10.3406/syria.1977.6623.

- Adam, Jean-Pierre; Mathews, Anthony (1999). Roman Building: Materials and Techniques. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20866-6.

- Addison, Charles Greenstreet (1838). Damascus and Palmyra: A Journey to the East with a Sketch of the State and Prospects of Syria, under Ibrahim Pasha, Vol. II. Philadelphia: T.K. & P.G. Collins for E.L. Carey & A. Hart.

- Alouf, Michel M. (1944). History of Baalbek. Beirut: American Press. ISBN 9781585090631.

- Arastu, Rizwan (2014). God's Emissaries: Adam to Jesus. Dearborn: Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya. ISBN 978-0-692-21411-4.[permanent dead link]

- Baldwin, Marshall W., ed. (1969). "The Rise of Saladin". A History of the Crusades, Vol. I: The First Hundred Years, 2nd ed.. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299048341.

- Baumgarten, Martin von (Martinus à Baumgarten in Braitenbach) (1594). Peregrinatio in Aegyptum, Arabiam, Palaestinam, & Syriam [A Trip to Egypt, Arabia, Palestine, & Syria] (in Latin). Nürnberg (Noriberga).

- Belon, Pierre (Petrus Bellonius Cenomanus) (1553). De Admirabili Operum Antiquorum et Rerum Suspiciendarum Praestantia [On the Admirableness of the Works of the Ancients and a Presentation of Suspected Things] (in Latin). Paris (Parisius): Guillaume Cavellat (Gulielmus Cavellat).

- Belon, Pierre (1554). Les observations de plusieurs singularitez & choses memorables, trouvées en Grece, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie, & autres pays estranges [Observations on the Many Singularities & Memorable Things Found in Greece, Asia, Judea, Egypt, Arabia, & Other Strange Lands] (in French). Paris: Gilles Corrozet.

- Bouckaert, Peter; Houry, Nadim (2007). Whitson, Sarah Leah; Ross, James; Saunders, Joseph; Roth, Kenneth (eds.). "Why They Died: Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War" (PDF). Human Rights Watch.

- Burkitt, Francis Crawford (1904). Early Eastern Christianity: St Margaret's Lectures, 1904, on the Syriac-speaking Church. London: John Murray. ISBN 9781593331016.[permanent dead link]

- Chesney, Francis Rawdon (1850). The Expedition for the Survey of the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris, carried on by Order of the British Government, in the Years 1835, 1836, and 1837; Preceded by Geographical and Historical Notices of the Regions Situated between the Rivers Nile and Indus. London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans.

- Chesney, Francis Rawdon (1868). Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition carried on by Order of the British Government during the Years 1835, 1836, and 1837. London: Spttiswoode & Co. for Longmans, Green, & Co.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard (1914). Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion. Vol. I: Zeus God of the Bright Sky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coulton, J.J. (1974). "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 94: 1–19. doi:10.2307/630416. JSTOR 630416. S2CID 162973494.

- de la Roque, Jean (1722). Voyage de Syrie et du Mont-Leban [Travel to Syria and Mount Lebanon] (in French). Paris: André Cailleau.

- De Saulcy, Louis Félicien Joseph Caignart (1853). Voyage Autour de la Mer Morte et dans les Terres Bibliques exécuté de Decembre 1850 a Avril 1851 [Travel around the Dead Sea and within the Biblical Lands undertaken from December 1850 to April 1851], Vol. II] (in French). Paris: J. Claye & Co. for Gide & J. Baudry.

- Frauberger, Heinrich (1892). Die Akropolis von Baalbek [The Baalbek Acropolis] (in German). Frankfurt: H. Keller.

- Genz, Hermann (2010). "Reflections on the Early Bronze Age IV in Lebanon". In Matthiae, Paolo; Pinnock, Frances; Marchetti, Nicolò; Nigro (eds.). Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: 5 May–10 May 2009, "Sapienza", Università di Roma. Vol. 2: Excavations, Surveys, and Restorations: Reports on Recent Field Archaeology in the Near East. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 205–218. ISBN 978-3-447-06216-9.

- Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths. Vol. I. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141959658.

- Hastings, James (2004) [1898]. A Dictionary of the Bible Dealing with Its Language, Literature, and Contents. Vol. IV, Pt. II. University Press of the Pacific in Honolulu. ISBN 978-1-4102-1729-5.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-263-4.

- Jessup, Samuel (1881). "Ba'albek". In Wilson, Charles William (ed.). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. II. New York: D. Appleton & Co., illustrated by Henry Fenn & J.D. Woodward. pp. 453–476.

- Jidejian, Nina (1975). Baalbek: Heliopolis: "City of the Sun". Beirut: Dar el-Machreq Publishers. ISBN 978-2-7214-5884-1.

- Kehrer, Nicole (21 November 2014). "Libanesisch-deutsches Forscherteam entdeckt weltweit größten antiken Steinblock in Baalbek" [Lebanese-German Research Team Discovers the World's Largest Ancient Stone Block in Baalbek] (in German). Berlin: German Archaeological Institute. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Köhler, Michael (2013). Hirschler, Konrad (ed.). Alliances and Treaties between Frankish and Muslim Rulers in the Middle East: Cross-Cultural Diplomacy in the Period of the Crusades. The Muslim World in the Age of the Crusades, Vol. I. Leiden: translated from the German by Peter M. Holt for Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24857-1. ISSN 2213-1043.

- Kropp, Andreas; Lohmann, Daniel (April 2011). "'Master, look at the size of those stones! Look at the size of those buildings!' Analogies in Construction Techniques Between the Temples at Heliopolis (Baalbek) and Jerusalem". pp. 38–50. Retrieved 13 March 2013.[dead link]

- Lamartine, Alphonse de (1835). Souvenirs, Impressions, Pensées, et Paysages pendant un Voyage en Orient 1832–1833 ou Notes d'un Voyageur [Remembrances, Impressions, Thoughts, and Passages concerning Travel in the Orient 1832–1833 or Notes from a Voyager] (in French). Brussels (Bruxelles): L. Hauman.

- Lendering, Jona (2013). Baalbek (Heliopolis). Livius. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.